Just a couple of months ago, pundits were writing off the Bank of Japan, and particularly Kuroda’s policy of 2% inflation. Now things are looking much more positive for the BOJ. Since plunging on the night of the Trump election, the Japanese stock market has taken off like a rocket.

It’s not hard to understand why—the yen has been in almost free fall, down from about 100 to the dollar to 118 today. To put that into perspective, back in April 1995, the yen was at 84 to the dollar. As recently as September 2012, right before Abenomics was announced, it was at 78 to the dollar.

But those numbers don’t even come close to showing what’s going on with the yen. What really matters is the real exchange rate. And since 1995, Japan has had an inflation rate that ran almost 2% a year lower than in the US. The US CPI is up by more than 57% since 1995, while the Japanese CPI is barely changed. Thus the real exchange rate for the yen has gone from 84 in 1995 to something like 180 or 185 today. At these levels, the exchange rate is a gold mine for Japanese exporters, which explains why the Japanese stock market is doing so well.

The big puzzle here is why PPP is failing so abysmally in terms of explaining the dollar/yen exchange rate. Generally when a country has persistently lower inflation than the US, its exchange rate tends to appreciate of time, and vice versa. Thus the Swiss have low inflation and the Swiss franc trends upwards. The Brazilians have high inflation and the Brazilian real trends downwards. And over the very long run that’s true of Japan as well. I recall when the yen was 350 to the dollar.

But since 1995 the yen has depreciated dramatically, even while Japan has had inflation rates that are roughly two percent less than the US. Of course during this period Japan has had much lower nominal interest rates than the US (at least the Fisher effect works!), and the yen has generally been expected to appreciate (due to the interest parity condition). Thus we’ve had a 21-year period where investors expected steady appreciation in the yen, and (on average) they got the exact opposite.

Going forward, one of two things will happen. Either the BOJ will persist with its inflation policies, or it will not. If it does persist, eventually investors will have to throw in the towel and admit that they were wrong about Kuroda. The yen will no longer be expected to appreciate, and the level of Japanese interest rates will be much closer to US rates.

Or, the BOJ will abandon it goal of 2% inflation, and the yen will start appreciating, just as investors have been predicting for 21 years. In that case, interest rates in Japan may stay close to zero.

It’s entirely up to the BOJ which road they prefer to take. A few months ago, many people thought they had given up. Today that’s much less clear. The higher global interest rates following Trump’s election, combined with the BOJ policy of pegging the 10-year bond yield at zero, has caused the yen to plunge in value. PPP is elastic, but not infinitely elastic. The yen can’t stay here indefinitely without generating serious inflation. Otherwise at some point a Lexus 430 would be as cheap as a candy bar.

My instincts tell me that this weird discrepancy between market predictions and actual outcomes can’t go on much longer. Within the next decade it will be clear whether Japan is seriously committed to a 2% inflation target. At that point, either Japanese interest rates will rise sharply (success), or the yen will appreciate sharply (failure).

PS. At Econlog, I have a post on Nick Rowe’s reply to John Cochrane, which might be seen as loosely relating to this post.

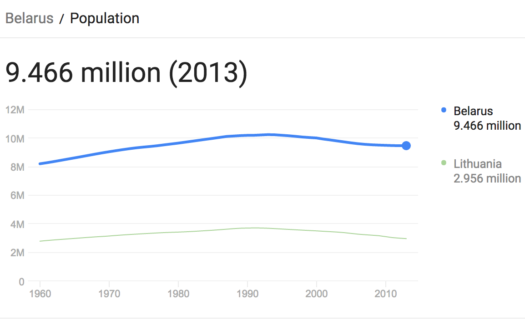

And yet Belarus has lots of inflation:

And yet Belarus has lots of inflation: Not as bad as the 100% inflation of 2012, but still running around 10% per year in recent years, despite a falling population.

Not as bad as the 100% inflation of 2012, but still running around 10% per year in recent years, despite a falling population.