Breakout

The new jobs numbers provide one more bit of evidence in support of the claims I’ve been making in this blog:

1. Job growth in the first 10 months of 2014 was almost 2.3 million, roughly the amount for the entire 12 months of 2012 or 2013. Thus the total for 2014 will end up being about 400,000 more than the average of the previous two years. That may reflect the expiration of extended unemployment benefits. Ditto for the still sluggish nominal hourly wage growth (stuck at 2.0%.) The household survey (less reliable) shows nearly 2.6 million jobs so far this year.

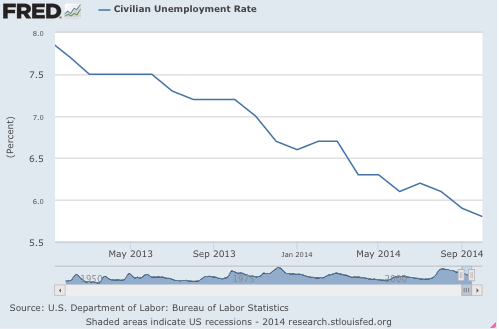

2. I’ve often referred to the fact that since the beginning of 2013 the unemployment rate has been falling at 0.1% per month, and will continue to do so. It did so again in October, down from 5.9% to 5.8%. That means we are only 4 months from the Fed’s definition of “full employment.”

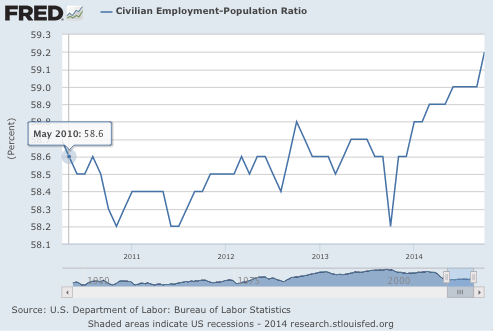

3. Some have pointed to the low employment/population ratio as evidence that we are not recovering. After being stuck in the trading range of 58.2% to 58.8% from October 2009 (when unemployment was 10.0% (exactly 5 years ago)) to February 2014, we finally have a decisive breakout on the upside:

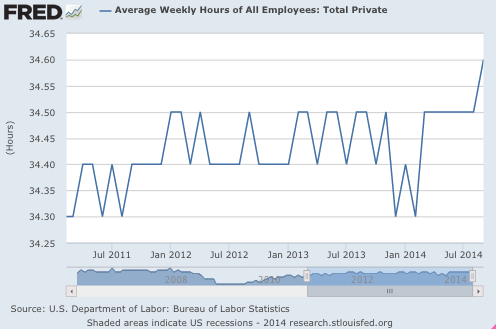

We also have a breakout for average weekly hours, which were stuck in the 34.3 to 34.5 range for years:

New claims for unemployment as a share of the workforce keep hitting all-time lows. Never in all of history did workers have less need to fear layoffs.

No Fed chairman ever had an easier job that Janet Yellen has right now. Normally you want to tighten before nominal wage growth accelerates. But in this case the Fed can wait for nominal hourly wage growth to accelerate from 2.0% to 2.5% before tightening, as the 2.0% figure is too low to hit their inflation target. So the Fed merely needs to wait until wage growth accelerates. No need to read the tea leaves.

(BTW, when I say “tighten,” I mean raise the fed funds target–policy is already tight.)

The last two years disproves several theories:

1. In January 2013 unemployment was still 7.9%, and many conservatives were pessimistic about the prospect for monetary stimulus to lower unemployment. They claimed we had “structural problems.” Now unemployment is 5.8% and still falling fast. We had a demand shortfall—in early 2013 wages hadn’t fully adjusted to the huge plunge in NGDP growth in 2008-09, and slow recovery.

2. Liberals claimed “austerity” in 2013 would slow the recovery. Exactly the opposite happened.

3. Liberals also claimed that ending extended unemployment benefits would not reduce unemployment (which was itself odd, because prior to 2008 liberals did believe that ending extended unemployment benefits would create jobs.) In fact the 2008 liberals were right, job growth accelerated in 2014 without any acceleration in wages. The acceleration was a “supply of labor-side” story. So while the overall recovery since late 2012 is a demand-side story, the acceleration in job growth after the first of the year was a modest supply-side addition to the recovery.

Despite all this good news, we could have done much better with a more expansionary Fed over the past 6 years. There are some “structural problems” in America, but they never had much to do with the near 10% unemployment rate of 2009-10.

PS. Tim Duy has an excellent post demolishing the conservative argument that the Fed is creating growth with “inflation.”

PPS. Here’s the steady fall in unemployment since January 2013. In contrast, from January 2012 to January 2013 unemployment had only fallen from 8.2% to 7.9%, which is why so many people were pessimistic “structuralists” at the time.

PPPS. The employment-population ratio for the all important 25-54 age group also rose, and has regained 2 points of the slightly over 5 points lost during the Great Recession. There’s still some slack out there.

HT: Garrett McDonald

Tags:

7. November 2014 at 07:40

Strong Household report. I found the “self-employed” component the past two months extremely interesting, as well as the breakdown by education (almost all gains in employed came from people without a bachelors degree).

7. November 2014 at 07:54

“Liberals claimed ‘austerity’ in 2013 would slow the recovery. Exactly the opposite happened.” – What is your proof that austerity accelerated the recovery (a recovery, that most are still calling too weak)? Brookings has come to the opposite conclusion and am interested in why you think they are wrong. http://www.vox.com/xpress/2014/11/6/7151881/austerity-US-economy-GDP

7. November 2014 at 07:57

The best part- it’s all private sector growth. Since the employment trough in January 2010, we have added 10.5 million private sector jobs and cut 420,000 government jobs. Little by little…

Hooray for gridlock.

7. November 2014 at 08:05

Scott, I didn’t word that very clearly. By “opposite occurred” I meant that growth increased. I do not think it increased due to austerity, which in my view had essentially no effect on the recovery.

Nonetheless, the predictions made by liberals like Paul Krugman were UNCONDITIONAL, as was their evidence of austerity’s negative effects in places like Europe. Krugman didn’t say growth would slow relative to no austerity, he suggested it would slow, period.

7. November 2014 at 08:06

And of course I agree that growth has been far too slow, due to tight money.

7. November 2014 at 08:35

Scott, be careful about using 25-54 year olds. Most of the remaining decline there is still due to some demographic shifts within the group and long term trends. I know it’s kind of a standard reference, though.

And, talk about monetary offset. Here is Janet Yellen in September 2008, describing her position in support of the consensus view to keep the Fed Funds rate at 2% with an eye toward inflation mitigation:

“Furthermore, we have seen a remarkable decline in inflation compensation for the next five years in the TIPS market. I would not rely heavily on this decline to support my view, but I do have to say that the decline is a lot more reassuring than the alternative. I was also encouraged by the 30 basis point drop in long-term inflation expectations in the most recent Michigan survey. I anticipate that the recent jump in the unemployment rate will place some additional downward pressure on growth in labor compensation, which has been quite low, and in core inflation.

Although the jump in the unemployment rate probably partly reflects the extension of unemployment insurance coverage, a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the upper bound on this effect is just a few tenths of a percent.” (pg. 34)

Leaving aside the idea that in September 2008 the FOMC was reassured by a precipitous decline in inflation expectations, note that Yellen here was explicitly saying that the Fed should ere on the hawkish side because Emergency Unemployment Insurance was escalating the unemployment rate, and thus masking inflationary wage pressures. The Fed tightening in September 2008 included monetary offset based partly on their belief that EUI inflated the unemployment rate. Keep in mind EUI had only been in effect for less than 3 months, at much less generous terms than its eventual terminus, and the unemployment rate was only 6.1%. I assume that the Fed’s hawkish offset increased as unemployment rose and EUI terms became more generous.

7. November 2014 at 08:53

Civilian employment to population ratio, with a much more informative view:

http://endoftheamericandream.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Employment-Population-Ratio-2014-460×305.jpg

Decisive breakout?

7. November 2014 at 09:07

If you dig into the demographic data in the jobs report, there’s a really remarkable surge in the number of teens (Age 16-19) who are now counted as being employed – finally breaking what has been a five year long doldrums of non-improvement for this demographic group.

What we think has begun happening in October is the result of falling fuel prices in the U.S., where they have finally fallen both enough and for long enough for the benefits to start affecting the jobs market. The effective discretionary income of consumers has increased, which is now showing up in the form of increased demand and revenue at businesses, which in turn have begun to pull more marginal workers onto their payrolls in response to the increased demand.

When it comes to marginal workers, there’s no demographic group that’s more marginal than teens. In October 2014, they accounted for roughly a third of the increase in the number of employed from the previous month. That’s where the real breakout has happened.

That would also account for why there was little to no wage growth for workers overall for the month – the teens being hired would be coming into the job market at or near the minimum wage level.

7. November 2014 at 09:23

“Here’s the steady fall in unemployment since January 2013. In contrast, from January 2012 to January 2013 unemployment had only fallen from 8.2% to 7.9%, which is why so many people were pessimistic “structuralists” at the time.”

Not this “structuralist”. And I’m no pessimist either.

An increase in “employment” does not disprove the structuralist theory. Structuralist theory is predicated on relative values and relative allocations of labor and capital, not aggregated ones. The very reason structuralism arose as a theory in the first place is because of knowledge of the economy that is masked by focusing on aggregates. Questioning aggregated statistical based arguments is part and parcel of structuralism.

It is when aggregate “employment” and “output” rise that structuralist theory becomes most needed as cooler heads cease to prevail when the focus is on increasing aggregates.

The question nobody is asking on this blog is whether or not all the RELATIVE labor allocations and RELATIVE capital allocations are physically sustainable, given that they have been made in what can be reasonably characterized as massively warped monetary conditions. Warped compared to what? Not compared to warping itself like the MMs believe (“The target is the standard”). Warped compared to what investors NEED to allocate labor and capital sustainably: free market prices, which requires free market money production.

The business cycle persists not because of belief in and “targeting” of the wrong god, e.g. price levels instead of spending levels. It persists because there is a faith in the socialist god to begin with. All non-market money distorts economic calculation. If there were ever a false belief, it is the belief that NGDPLT will somehow succeed in “reducing” or “minimizing” the intensity of recession cycles. All it can do is DELAY. Delay. That is a word that should enter into the minds of all MMs.

All the Fed did since 2009 is DELAY the full correction. They did not fail and then gradually succeed. They delayed pain to the future, and brought MORE future pain along.

Aggregates mask this.

7. November 2014 at 11:33

So it will take 7 years or so to fix most of the effects of the 10-12% ngdp shortfall of 2008-2009 with 4% ngdp growth. Give or take, we repaired the equivalent of a 1.5% shortfall in NGDP every year.

If the Fed had set NGDP growth at 5%/year through a mix of QE and forward guidance, market monetarism predicts that annual wage growth would have been roughly the same (say under 2% per year), and that the gap would have been closed in 4-5 years instead of 7 years. Is that right?

7. November 2014 at 13:44

Following up on my earlier comment, it seems like there is an uber-monetary offset.

To me, it seems likely that policies such as the minimum wage hikes and emergency unemployment insurance that were implemented during the crisis, on net, raise inflation but lower real production. As a first order effect, they both pull workers out of production while intending to increase consumption. I know there are widespread ideas about how the added consumption is supposed to increase real production, but the presumption sure seems like it should be that these policies mean more money is chasing less production.

But, it seems like the Fed tends to accept the idea that these policies are stimulative. If that is the case, and, further, if the Fed also tends to make adjustments in their interpretation of data such as Janet Yellen’s trimming down of the true unemployment rate, then the Fed could be making additive adjustments in policy as a result.

So, we have policies that may be increasing inflation and decreasing production because these are basically labor market supply shocks, and the Fed’s reaction to these policies may be highly disinflationary. A combined inflationary supply shock from labor policy leading to a deflationary demand shock from monetary policy. This would end up leading to middling inflation but low RGDP growth. And, if the Fed was misinterpreting the effect of these labor policies and then kind of double counting the effects, this would even lead to inflation levels below the Fed’s target.

If this is the case, monetary offset would more than counteract fiscal policy.

7. November 2014 at 14:52

@Kevin, fascinating notion.

7. November 2014 at 15:53

Excellent blogging. Americans have given up trillions of dollars in output and millions of jobs for scant reduction in inflation.

I do not even want to think about Europe.

7. November 2014 at 17:53

Seeing so much “sound money” nonsense on the right, it’s really depressing.

I have a giant political crush on Rand Paul, but I’m starting to worry his election might lead to some really, really bad monetary policy.

8. November 2014 at 05:40

Thanks Kevin, I’ll do a post.

Ironman, Interesting, but recall that the breakout began earlier in the year, before oil prices fell.

LK, I’d say it will take 6 years for complete recovery (2009-15), 4 years with 5% NGDP growth, and less than 4 years if policy had tried to catch up to the original trend line.

8. November 2014 at 07:50

As much as I hate discussions of monetary policy centering on interest rates, this from UC Irvine’s Eric Swanson is pretty clever;

http://www.voxeu.org/article/zero-lower-bound-has-not-been-very-severe

———-quote———-

… from 2009 to mid-2011, Blue Chip survey participants consistently expected that the Open Market Committee would begin to raise the federal funds rate in just 4 quarters’ time. Only beginning in August 2011, when the Committee issued an explicit statement that it expected to keep the funds rate near zero “at least through mid-2013″, did the Blue Chip forecasters’ expectations of policy tightening get pushed out further, to a horizon of 7 quarters or more.

….

These results have important implications for monetary and fiscal policy. For monetary policy, they suggest that the Open Market Committee could have done more to ease policy between 2009 and late 2011. In retrospect, it clearly could have lowered one- and two-year yields further by promising to keep the federal funds rate low for a longer period of time. Only beginning in August 2011, when the Committee issued its ‘mid-2013’ forward guidance, do we see those longer-term interest rates fall to the point where they were more significantly constrained by the zero lower bound. Going forward, one of the lessons from the analysis above is the power of the Committee’s explicit forward guidance to influence longer-term interest rates and thereby the economy.

For fiscal policy, the results suggest that crowding out would not have been very different from normal between 2009 and late 2011. Although the federal funds rate was stuck at zero, one- and especially two-year yields were largely unconstrained during this period. As a result, the ARRA fiscal stimulus package passed in 2009 likely raised interest rate expectations in the usual way and crowded out the effects of the stimulus by the usual amount.2 This is one factor that could help explain why the economic recovery has been so disappointing, despite the very large fiscal stimulus package passed early on (see Romer 2012, Frankel 2014, and Fischer 2014 for discussions of the weak recovery and post-mortem analyses of the stimulus).

————-endquote———-

8. November 2014 at 09:30

The Fed has been very reluctant, in the face of “inflation hawk” opposition, to de the modest amount of stimulus that it has done and is chomping at the bit to raise rates. In view of the slow recovery in the employment/population ratio, and that NGDP has not yet returned to its pre-crisis trend, it might be a good idea to re-think whether 5% unemployment of the diminished labor force really represents full employment.

8. November 2014 at 12:27

TallDave –

“I have a giant political crush on Rand Paul, but I’m starting to worry his election might lead to some really, really bad monetary policy.”

Might lead to bad monetary policy? It’s a certainty.

http://www.salon.com/2014/02/05/rand_pauls_monetary_fear_mongering_debunked_what%E2%80%99s_his_story_where_the_fed_goes_under/

“Sen. Rand Paul took to the floor to accuse the Fed of “laundering money from the American people” and warn that “the once proud dollar that was once backed by gold … is now backed by used car loans and underwater mortgages.” Citing an author calling the Fed “insolvent,” Paul told the Senate he was “concerned that we have papered over the problems in a sea of new currency.””

There is a link to his speech in the article. It’s all gold standard nostalgia. Rand Paul is a hard money nut.

8. November 2014 at 12:41

Thanks Patrick.

Thomas, Here’s an even better idea—ignore the unemployment rate entirely when setting monetary policy.

Negation, I guarantee that Rand Paul will not put us back on the gold standard.

8. November 2014 at 13:33

The bond market yields and market-implied inflation expectations continue to breakout to the downside. The employment data may be positive, but is scaring the bond markets witless about too early tightening.

10. November 2014 at 07:16

James, We are getting a classic supply-side recovery. A demand-side recovery would have been much faster, but the economy will eventually self-correct either way.

10. November 2014 at 10:51

Scott. Interesting.

Problem remains that any rise in short term rate expectations now would quickly invert the yield curve – as mid and long term rates are so low already, and trending lower – and then act as the classic predictor of a recession.

Question is: how many classic supply-side recoveries have been accompanied by falling long term yields?

10. November 2014 at 19:37

James, That’s been my concern for a while. I don’t think the policy stance “right now” is a huge problem in and of itself. We can grow this way. The real problem is that we don’t have the sort of regime that would prevent the same problem from occurring again. It’s potentially unstable.

I seem to recall long bond yields fell a bit in the previous two US recoveries, or at least were surprisingly low in the case of the 2003 recovery.