An extraordinarily accurate and highly disturbing prophecy from 1989

I recently came across a very interesting essay written by Paul McCulley (of PIMCO) in 2001. At one point he discusses a bizarre idea that got a foothold at the Fed in 1989:

For the last decade, the Fed has played something called “opportunistic disinflation,” and it, too, has worked.

The term actually entered the public arena on July 10, 1996, when the Wall Street Journal leaked an internal Fed report by staff economists Orphandies and Wilcox, detailing the Fed’s “new” approach to inflation-fighting: the Fed should not take deliberate action to reduce inflation, but rather “wait for external circumstances – e.g., favorable supply shocks and unforeseen recessions – to deliver the desired additional reduction in inflation.”

Simply put, the theory said, the Fed should not deliberately induce recessions to reduce inflation, but rather “opportunistically” welcome recessions when they inevitably happen, bringing cyclical disinflationary dividends. A corollary of this thesis was that the Fed should pre-emptively tighten in recoveries, on leading indicators of rising inflation, rather than rising inflation itself, so as to “lock-in” the cyclical disinflationary gains wrought by recession. While the label “opportunistic disinflation” was a clever one, the Fed had actually been practicing the policy for a long time. Indeed, former Philadelphia Fed President Edward Boehne elegantly described the approach at a FOMC meeting in late 1989:

“Now, sooner or later, we will have a recession. I don’t think anybody around the table wants a recession or is seeking one, but sooner or later we will have one. If in that recession we took advantage of the anti-inflation (impetus) and we got inflation down from 41/2 percent to 3 percent, and then in the next expansion we were able to keep inflation from accelerating, sooner or later there will be another recession out there. And so, if we could bring inflation down from cycle to cycle just as we let it build up from cycle to cycle, that would be considerable progress over what we’ve done in other periods in history.”

Before discussing the Boehne quotation, think for a moment about just how strange this “opportunistic disinflation” idea really is. Suppose you are trying to lose weight. You notice that extremely ill people often lose weight. Voila! A cancer diagnosis is a perfect “opportunity” to lose some weight. Of course you don’t want to go on a diet when suffering from cancer, (that would be going too far), but on the other hand don’t go out of your way to eat food either. Just enjoy the weight loss.

There are basically two types of macroeconomists in academia. Those (mostly right-wing) who favor a strict inflation target. In that case inflation would be the same whether we are in a recession or boom. Others favor some sort of flexible inflation target. NGDP targeting is a good example. When real growth falls, you allow inflation to rise a bit. This reduces the severity of the business cycle during supply shocks.

But within the halls of the Fed a third and very dangerous idea took hold during the 1980s and 1990s, opportunistic disinflation. This ideas suggests that the fall in inflation rates often observed in recessions is not a failure of demand management, not a highly procyclical monetary policy, but something to be welcomed.

Now at this point I know my more sensible readers are starting to roll their eyes. “Yes, a few oddballs at the Fed put forth this theory, but you don’t mean to seriously suggest that such a wacky idea, with almost no support in academia, would be embraced by the Fed itself?”

Go back and read the Boehne quotation. As of 1989, inflation had average about 4.5% over the previous 7 years. The bond markets clearly indicated that inflation was likely to stay high, indeed go even higher. But Boehne had inside information, he worked at the Fed and understood that in the next recession the Fed was determined to reduce inflation to 3% and keep it there until the following recession. And in the following recession they would reduce it a bit further, and so on. And that is what happened. Inflation fell to 3% percent in the 1990s. The next cycle didn’t see much further reduction, but only because of the huge 2006-08 oil shock. If not for Asian oil demand, the Fed would have delivered a further reduction in inflation. Now that oil prices are down, we have inflation falling to about 1% in this cycle.

Boehne was very accurately predicting a Fed policy that would almost inevitably drive the economy off the cliff, only he didn’t realize it. Opportunistic disinflation means that inflation falls at the same time that RGDP is falling. If you start from a position of already minimal inflation, and have a steep recession, and the Fed does nothing to offset the fall in inflation typically associated with steep recessions, then you can get a fall in NGDP. As I keep pointing out, NGDP in 2009 fell at the sharpest rate since 1938. And both 1938 and 2009 saw near-zero interest rates. Boehne did not recognize that this sort of policy could drive the economy into a liquidity trap. But he can be forgiven for that oversight, after all, with Treasury-bill rates up around 8% in 1989, few people even considered the possibility of 1930s-style liquidity traps returning.

Bernanke and Greenspan saw what happened in Japan in the 1990s, however, and that ‘s why the Fed seemed to ease aggressively in 2002. In fact, monetary policy was not very expansionary, but at least they understood the problem. Unfortunately, they didn’t recognize just how dangerous the Fed’s opportunistic disinflation policy had become.

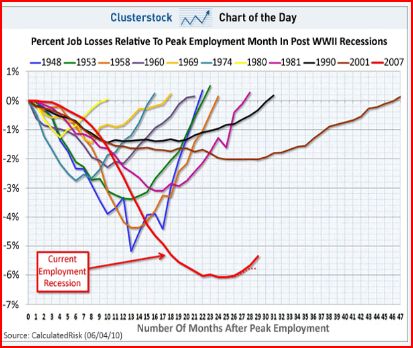

The following graph shows that the jobless recovery of 2010 is nothing new, the previous two cycles had the same problem, it’s just that they were much milder, so fewer people noticed.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

I found this graph in Erik Brynjolfsson’s blog, which also contained this provocative post:

As growth resumes, millions of people will find that their old jobs are gone forever. The jobless recovery is one symptom.

Two points. There are no jobless recoveries. If you don’t generate jobs, you have no recovery—regardless of whether RGDP is growing. And second, people normally don’t get their old jobs back, in this recession or in any other recession. How many people return to their old jobs after being laid off? I read somewhere that during a typical year there are about 32 million jobs lost and about 33 million jobs created. I’d wager that very few of those jobs created are people getting their old jobs back.

The post was entitled “The Great Recalculation.” But if the Fed is doing its job then recalculation should produce stagflation. Lower output should mean higher inflation. But that’s not what we are seeing. It is possible that there is an unusually large amount of recalculation going on, although in my view that mostly occurred before the severe phase of the recession began in August 2008, but in any case it is observationally indistinguishable from opportunistic disinflation.

I recall reading about opportunistic disinflation in the 1990s, and making a mental note that it was a silly idea, obviously procyclical, and that surely the Fed would not take the idea seriously. Shame on me. The Fed warned us what they planned to do as far back as 1989. We ignored them. Then they went ahead and did it. And they are still doing it. This expansion will have even lower inflation that the last one.

PS. Paul Krugman deserves some credit for anticipating this problem.

Tags:

21. July 2010 at 14:02

If the above post is accurate then I have been right all along – Bernanke (or the Fed as a whole) likes what we now have, and is determined to give us more of it.

Bob Reich of course doesn’t. He is, of course, a Democrat. But is Obama?

http://wallstreetpit.com/36509-we%E2%80%99re-in-a-one-and-a-half-dip-recession

quote from Reich

And what about the Fed? It’s the last game in town. The 1.5 dip recession should cause Ben Bernanke to revert to buying mortgage-backed securities, buying Treasury bills, buying anything that will get more money into circulation.

But the Fed chair continues to talk about pulling money out of the system and raising short-term rates as the economy improves. During Wednesday’s appearance before Congress he made it clear monetary policy won’t be loosened; it just won’t be tightened for a while. And he reiterated that deficits were “unsustainable.”

He admitted unemployment would probably remain high for a long time, and the likelihood of growth was “weighted to the downside,” which in Fed-Speak means we’re still in trouble. And he said the Fed still has the tools to do what’s needed if the economy needs more help.

But would he use the tools now? No. “We need to look at them carefully to make sure we’re comfortable with any steps that we take.” This is like the captain of the Titanic looking carefully at his lifeboats to make sure he’s comfortable with using them as the ship starts sinking.

end quote

In a previous post Scott accused the Fed of abuse of power. This is a very strong accusation – but the above post would explain it.

Obama should now demand that the Congress take the Fed back –

toss the deflationists out and start over again.

21. July 2010 at 14:18

Off topic in a way, but I’m commenting in July, so I’d note that Lance Armstrong was a cancer patient who didn’t particularly mind the associated weight loss. Some of us believe that, doping or not, he’d never have won a Tour if he hadn’t lost the weight he lost then.

21. July 2010 at 14:22

I’ll say it again: The best economic commentator going right now is Scott Sumner.

Hard to argue with this post. People, ensconced (sometimes for decades) in large organizations, usually come to adopt the mannerisms, thoughts, biases, etc. of that organization.

Anybody in real estate now knows we need a huge boost, and that inflation would be great. Fed bankers? They have their own notions, and nearly a religion around price stability. I guess we are now targeting absolute price stability–zero inflation.

Nobody wants accelerating inflation–but price stability at the price of real output?

I’ll say it again–I would rather live through a long inflationary boom than a long deflationary recession. I am not sure those sentiments are the same at the Fed.

21. July 2010 at 14:27

Krugman´s “identification” of the “opportunistic disiflation strategy:

Paul Krugman in his Age of Diminished Expectations (1994, page 108) writes: “… economists are still puzzled by the suddenness of the slump that developed in 1990, in particular by an abrupt decline in consumer confidence … one answer is that during the early stages of the slump the Fed.’s mind was on other things. In the late 1980’s, there was considerable agitation by conservative economists and their congressional allies for a U.S. policy aimed not simply at holding the line on inflation but at achieving complete price stability. The Fed wasn’t prepared to launch another all-out war on inflation, but it was willing to contemplate some rise in unemployment… one Fed economist remarked to me at about that time that: ‘we can’t go out and create a recession, but we can try to take advantage of any little recessions that come along”.

21. July 2010 at 15:27

This is a very interesting post and almost unbelievable.

To mention Reich, his blog is among the 4 or so I read first, along with this one. I almost always agree with him/

21. July 2010 at 15:32

In a way, this reinforces the whole fiscal vs. central bank “The monetary authority moves last, and he who moves last wins” ideas.

The incentives of any administration would be almost opposite this scheme, in that they would like to have “opportunistic inflation”, that is, to take advantage of emergency events and use the crisis as cover to debase the currency, boost employment, and lower the real value of debt.

But a fiscal authority stimulating with an eye to opportunistic inflation is not just neutralized but *outweighed* by a later moving, independent monetary authority attempting opportunistic disinflation.

I think JimP has it right – the Fed thinks it’s doing the right thing, and will only do more if absolutely compelled to do so by a new and dramatic deterioration in conditions.

21. July 2010 at 16:00

I am now reviewing the testimony Bernanke gave to the Senate today. I am socked that the senators weren’t all over him when he said something like, ‘We can do more and will if things get worse.’ How much worse does the economy need to be? Worse than 2009 or 2008? Worse than now? He hasn’t explained why the Fed isn’t doing more and insists monetary policy is now quite accomidative. How so? I’m sensing an aura of ‘Let them eat cake’ and the senators are just clueless.

21. July 2010 at 16:03

Their incompetence knows no bounds.

Need I say it?

End the Fed.

21. July 2010 at 16:55

Completely unrelated:

Essential flashback reading, from May 2007!

“Despite making only $14,000 a year, strawberry picker Alberto Ramirez managed to buy his own slice of the American Dream. But his Hollister home came with a hefty price tag – $720,000.”

http://hollisterfreelance.com/news/contentview.asp?c=213141

Wow…

21. July 2010 at 17:08

In this light, it seems all of us misinterpreted Bernanke’s famous QE speech. We all thought he meant to reassure us that the Lost Decade could not happen in the US.

We were wrong –

What Bernanke really meant to say was that there’s no reason for the 2% inflation target. The justification for 2% was to give the Fed the ability to drop rates to compensate for an AD shock.

But if you have access to QE tools, you don’t need that wiggle room – you can keep an inflation target at 0%, and manage using QE rather than rate drops.

21. July 2010 at 18:40

It’s worth noting that Fed long run inflation forcasts still say 1.7-2.0, which suggests they have not changed.

21. July 2010 at 18:40

Also, even Thoma, a monetary policy skeptic, seems baffled by the Fed http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2010/07/why-are-the-feds-options-still-under-review.html

21. July 2010 at 18:44

There is an interesting intersection between this idea and the observation that the business cycle seems to be lengthing.

Its not the business cycle that got longer but that the Fed decided to stop triggering recessions with tight money. So as every intentional recession must happen sooner than the next natural one, the business cycle would appear to lengthen.

21. July 2010 at 18:54

Many businesses would consider firing people to outsource their jobs unethical. Not so many would consider it unethical to avoid hiring as demand picks up by asking foreign suppliers to add services and build the cost into the price of the product. Doing so has another benefit; for them, the labor cost is perfectly variable.

There are many reasons why, if and when demand returns, labor will lag. Rising domestic administrative and overhead costs and increasing capability of overseas labor are two of them.

Notice that rising overhead cost alone will extend the recession. Every small business owner I know (20+) has told me they are remaining their present size on purpose; it’s not worth the headache to grow. The economy will have to wait for new entrepreneurs to sense unmet demand, successfully enter the market and stay there, which is more difficult than it sounds.

21. July 2010 at 20:13

Am I the only one that noticed this narrative leaped from ~1991 to ~2007, totally skipping the downturn in 2000-2001?

21. July 2010 at 20:15

I should clarify, I know that it is mentioned, but I mean that it is left out of sequence.

21. July 2010 at 22:33

Could this policy explain why we have had deeper recessions lately?

What would the next step, what will happen when you enter the next recession with even lower inflation? Would the Fed respond more aggressively then when there’s not much inflation to lower?

It would be ironic for the gold bugs though. They are convinced that Bernanke is destroying the currency and laying the ground for hyperinflation.

22. July 2010 at 04:32

[…] Via Scott Sumner, Paul McCulley discusses the strange theory of “opportunistic disinflation” that was bandied about in Fed circles in the late 1980s: Simply put, the theory said, the Fed should not deliberately induce recessions to reduce inflation, but rather “opportunistically” welcome recessions when they inevitably happen, bringing cyclical disinflationary dividends. A corollary of this thesis was that the Fed should pre-emptively tighten in recoveries, on leading indicators of rising inflation, rather than rising inflation itself, so as to “lock-in” the cyclical disinflationary gains wrought by recession. While the label “opportunistic disinflation” was a clever one, the Fed had actually been practicing the policy for a long time. Indeed, former Philadelphia Fed President Edward Boehne elegantly described the approach at a FOMC meeting in late 1989: […]

22. July 2010 at 05:11

@ThomasL

“Am I the only one that noticed this narrative leaped from ~1991 to ~2007, totally skipping the downturn in 2000-2001?”

That downturn was really mild.

1.Anyway, equity based downturns shouldn’t be as bad as debt based downturns.

2. We didn’t have the fed crushing NGDP.

22. July 2010 at 06:26

In the Fed’s defense, many people think that a steady 4 percent inflation is too high, and 1 to 2 percent is better. Some even think that a long-term average rate of zero inflation is best. If, as most economists believe, price indices understate inflation, then even zero measured inflation is still a positive rate.

So let’s assume for a minute that it’s 1990 and you favor a long run inflation rate 3 or 4 percent lower than it was then. How do you get there? I used to favor an announced target path for an expected broad price index. Scott has persuaded me that an announced target path for expected NGDP is better. But the Fed, like every bureaucracy, does not want the accountability that would come with a numerical target. If you rule that out, how do you lower inflation? Given your assiduous avoidance of blame, you’re not likely to deliberately induce recessions. Volcker could do it only because double digit inflation really scared people. Opportunistic disinflation may be the best you can do.

It bears repeating that this sad outcome really results from the refusal to commit to a numerical target that could be easily monitored by Congress and the public. I’ve never understood why this is so important to the Fed, but long observation has convinced me that it is. Part of it may be that, as Arnold Kling says, if the central bank’s response function is simple and well-understood, the Fed loses prestige. Or it may be that political liberals do not want to acknowledge that good monetary policy obviates the need for fiscal stimulus.

OK, so I lied: this really isn’t much of a defense of the Fed at all.

22. July 2010 at 09:32

From a speech by Fed Governor Laurence Meyer in 1996:

Opportunistic Disinflation

“A couple of years ago, I gave the name “opportunistic disinflation” to an alternative strategy for bridging between short-run policy and long-run goals, a strategy that I observed the Federal Reserve to be following at the time. I will use this strategy this evening to describe my own position. But I want to make clear that I am not speaking for others on the FOMC or describing official policy. Under this strategy, once inflation becomes modest, as today, Federal Reserve policy in the near term focuses on sustaining trend growth at full employment at the prevailing inflation rate. At this point the short-run priorities are twofold: sustaining the expansion and preventing an acceleration of inflation. This is, nevertheless, a strategy for disinflation because it takes advantage of the opportunity of inevitable recessions and potential positive supply shocks to ratchet down inflation over time. Proponents of this strategy sometimes describe this approach as reducing inflation cycle-to-cycle or describe the economy as being one recession from price stability. Under this strategy, if growth were to slow to trend, the unemployment rate were to remain where it is, and inflation were to remain stable, monetary policy would remain on hold, ready to respond aggressively to any acceleration of inflation, but otherwise prepared to be patient and accept the lower inflation that will accompany the next recession or favorable supply shock.

This is just another rule, though a more complicated one than the simple Taylor Rule. It also links short-run policy actions to long-run objectives, juggles multiple targets in a disciplined way, and would be successful in achieving the long-run objective over time”.

Could he imagine at what cost!

22. July 2010 at 12:22

This hypothesis is terrifying. This way of is completely absurd on the economic point of view.

Alas, on a political point of view, this is frighteningly seducive: find a scapegoat (a real supply schock) on which to blame

22. July 2010 at 12:26

This hypothesis is terrifying. This way of is completely absurd on the economic point of view.

Alas, on a political point of view, this is frighteningly seducive: find a scapegoat (a tiny real supply schock) to make accept destructive but prestigious policies (reducing the inflation rate).

22. July 2010 at 15:02

JimP, Yes, that’s a good quotation.

Thomas, Even as I wrote that I had a sneaking suspicion that it wasn’t quite the right metaphor. I’d thought people lost too much weight during treatment for cancer, but maybe it was some other disease.

Thanks Benjamin.

marcus, Yes, I recall that Krugman has pointed out the agenda of steadily reducing inflation each cycle.

Mike. I agree with Reich on monetary policy right now, but there are many issues where he is to the left of me.

Indy, That’s a good point.

Bonnie, I agree. And by the way I don’t think I saw all the questions, just the main testimony and a few questions in the link I provided. If anyone sees any other important questions and answers, let me know.

Indy#2, And I sort of knew that that was going on, but will admit that I didn’t pay as close attention as I should have. It really did get crazy. I’m sure many of you commenters were more on top of the RE bubble than I was–it wasn’t so extreme in Boston. Many banks around here are doing ok.

Statsguy, You may be right, but then he isn’t using the QE to the extent that he needs to. The memoirs will be very interesting.

John Salvatier, That’s a good point. But I’ll bet that in the mid 1990s, when inflation was around 3%, the long run projections were higher than 1.7-2.0%. I think they lower the trend inflation first, get people used to it, then gradually admit that their projections are actually lower. It would be highly unpopular to admit to reducing an inflation target right in the middle of the recession. BTW, I find the 1.7 figure interesting. They have never acted like that was their target (before this recession.) Inflation was well over 2% for much of the 2000s, and they weren’t raising rates after 2006. Indeed they cut rates several times in 2007 when inflation was well above 2.0. So I think the de facto target was above 2%, but now the de facto target is below 2%. Time will tell.

Jon, I have been thinking about that a lot, but still haven’t reached a conclusion. The Fed has probably lengthened the upswings, which used to average only about three years. But the periods of high unemployment also seem lengthened, perhaps for the same reason. Extended unemployment benefits might also keep unemployment a bit elevated, but I have a hard time believing that is the primary factor.

I also sometimes wonder if this is a function of our post manufacturing economy. The Asian countries that still do a lot of manufacturing had more of a traditional V-shaped recession. There might be multiple reasons, but monetary policy is a likely culprit.

Whiskey Jim, You may be right, but does it explain why the pattern developed over the last three cycles? Is it a post-manufacturing phenomenon? (BTW, I do know we do a lot of manufacturing, but it is a much smaller share of jobs than it used to be.)

ThomasL, I believe I mentioned briefly that the Fed seemed to be engineering lower inflation after the 2001 recession, compared to the 1990s, but that record was marred a bit by the huge oil shock. I haven’t looked at the data recently, but I believe core inflation fell after 2001. This cycle is clearly lower again. I’m old enough to recall when people thought inflation was “conquered” in the 1980s, and it was 4.5% after 1982!!

Mattias, But we haven’t so much had deeper recessions, but rather longer recessions. This was fairly deep, but 2001 was very shallow, but with an extremely drawn out jobs recovery. The 1991 recession was not that atypical, but again a slow recovery.

Jeff, I actually think it is possible to gradually reduce inflation during a boom. We were succeeding in the 1990s up till about 1998. Then the Fed panicked with LTCM failing and the foreign crises, and got too expansionary. That pumped up NGDP in 1999-2000, as I recall. If they’d stayed tighter after 1998, and not let NGDP rise, we could have continued the progress in gradually lowering inflation that occurred between 1992-98. BTW, this is all from memory, so the years may be a bit off, and the changes were very gradual.

Marcus, Yes, I ran into that quotation when working on the post.

Jean, Yes, the Fed can just blame the recession, not their policy.

22. July 2010 at 16:12

@Scott:

“I recall reading about opportunistic disinflation in the 1990s, and making a mental note that it was a silly idea, obviously procyclical, and that surely the Fed would not take the idea seriously. ”

You underestimated the political economy. Remember, everyone, especially regulators and policymakers are self interested.

@Whiskey jim:

“Notice that rising overhead cost alone will extend the recession. Every small business owner I know (20+) has told me they are remaining their present size on purpose;”

The marginal regulatory burden on business as a function of employee size becomes immense near 50 employees. It really makes a lot of disincentive for growth from employee expansion. I have a feeling the next few cycles we will see more and more growth from productivity enhancements and less from employment expansion.

22. July 2010 at 20:51

@Scott and Doc:

does it [outsourcing] explain why the pattern developed over the last three cycles? Is it a post-manufacturing phenomenon?

Partly I suppose. There are a number of conflating effects. One is technology and the Internet smoothing transaction costs, enabling buyer / seller meetings, and communication in general. And fifteen years say, is a long time for millions of people to learn English and develop marketable skills.

Remember, outsourcing as we call it is not the only issue. New business no longer has to originate domestically. Just go hire the talent on a contract basis off the Internet. There are incredibly talented people around the world. Many are live at home mothers in the heart of what we consider third world countries.

It is beyond ironic that as business (including large firms) flattens and empowers individuals and entrepreneurial activity, drawing closer to the autonomous agent complex system model, domestic government policy becomes ever more controlled and hierarchical. There is a huge disconnect there. Labor is becoming as mobile as capital. You can not tax it and regulate it in a cocoon.

As for marginal costs of overhead, remember the psychology as well. A great number of people worked very hard the last 10 years to get ahead, and now it’s all gone. They’ll never work hard again. It’s not worth it. Besides, the government is coming, and everyone knows it.

22. July 2010 at 23:42

@WhiskeyJim:

“does it [outsourcing] explain why the pattern developed over the last three cycles? Is it a post-manufacturing phenomenon?”

Garett Jones has been saying that the reason is in the new economy, workers don’t build goods, they build productive capacity. This means that employment growth should be MUCH slower than GDP growth now.

I don’t know what outsourcing may have to do with it, unless it just is outsourcing to china because of supply side barriers in the US?

23. July 2010 at 17:55

Ah, sorry Doc.

I’m saying the trend to view labor as an international commodity is growing by leaps and bounds, and it doesn’t necessarily clearly show up in the numbers: on a macro level, GDP would remain constant, margins would go down slightly (the new foreign services labor is included in the price), and displaced domestic employment would be slightly down, so it would look like a productivity increase, wouldn’t it?

And like you implied earlier, there is a huge marginal cost to growing here domestically. We are encouraging employers to go international, and it is increasingly easy to do. We are quickly reaching a tipping point where the trend becomes a river for services as well; legal, advertising, etc.

Your clarification reminds of another dampening trend; firms are getting over their cultural aversion to work-from-home, which means less consumption.

Question: if say, 10% of people stopped going to the office (implying closing or selling buildings), wouldn’t that look like slower growth (decreased energy, less building, etc) rather than more efficient production?

24. July 2010 at 16:17

Doc Merlin, That’s a good point. Here’s one way to create jobs–lift the regulatory exclusion from 50 to 100. Lots of small firms that are doing well may add additional employees.

WhiskeyJim, I’m sure there’s a lot of truth in what you say. What I constantly struggle with is separating the long run trends from factors that would influence the business cycle.

24. July 2010 at 16:21

@Scott

‘Doc Merlin, That’s a good point. Here’s one way to create jobs-lift the regulatory exclusion from 50 to 100. Lots of small firms that are doing well may add additional employees.’

Hrm, I’ll call my congressman and suggest it.

29. July 2010 at 09:50

[…] only deciding to go for zero during the worst financial crisis in American history? Oh, I forget, opportunistic disinflation. (aka: “Having cancer is a good opportunity to lose some […]

29. July 2010 at 11:08

Have you seen the film The Devil Wears Prada. There’s a line, “I’m one stomach virus away from my goal weight!”

29. July 2010 at 18:01

[…] was unique to some feature of Japan itself, and cannot happen in the US. But perhaps we have quirky features as […]

30. July 2010 at 05:55

Andy, No but I like that line.

4. August 2010 at 13:02

Scott

Just remembered they missed their grand opportunity at OD in 2002-03 when inflation came down close to 1% and instead of keeping AD steady at something close to 5% they jacked it up to 7%+. They were afraid of the disinflation sliding into deflation then (which was of the benign kind – due to productivity increase) and are not afraid (Fischer even welcomes) desinflation today with close to 10% unemployment!

6. August 2010 at 06:37

marcus, Yes, it does seem inconsistent.

8. September 2010 at 09:54

Scott,

I thought that Opportunistic Disinflation was the policy of the Fed until roughly 1998, and it was abandoned entirely in 2002, IMO.

One reason for its abandonment had to do, not just with Japan, but also with Argentina. The view is that Argentina under Cavallo and convertibility was TOO successful: its low inflation rate made it hard to reduce real wages, and therefore restricted Cavallo’s room to maneuver the economy out of its slower-growth trajectory. You might say, “Japan was much more important”. Except that Japan was an analogy of failure — by 1998 it had already undergone ten years of crisis. By contrast, Argentina was seen as an example of the resounding success of disinflation.

So Cavallo’s problems meant that true price stability was unwelcome. Throw in Japan’s deflationary issues, and it is no surprise that Greenspan/Bernanke adopted the “inflation cushion against deflationary shocks” approach in 2002. That sea-change in policy roughly coincided with the bottom in gold prices. Now, before you call me a crazy gold bug, I am talking about long-term trends which have more “signal” than “noise”. Under first “inflation-fighting” and then “oportunistic disinflation”, gold had a twenty year bear market. Under “inflation cushion against deflationary shocks”, a ten year bull market.

9. September 2010 at 07:12

David Pearson, I also thought it had been abandoned. But as Krugman would say “It’s Baaack”

7. October 2011 at 09:54

[…] and TheMoneyIllusion link to sites explaining “opportunistic disinflation.” It’s a questionable […]

1. February 2013 at 05:21

[…] looking at falling inflation the previous few decades. Not that we have to guess. Fed president Edward Boehene actually laid out this approach in 1989, and Fed governor Laurence Meyer endorsed the idea of […]

1. February 2013 at 11:13

[…] looking at falling inflation the previous few decades. Not that we have to guess. Fed president Edward Boehene actually laid out this approach in 1989, and Fed governor Laurence Meyer endorsed the idea of […]

17. September 2013 at 14:29

[…] the bust too. This was a pernicious idea that took hold at the Fed in the late 1980s called “opportunistic disinflation.” It went something like this. The Fed could tighten policy to lower inflation, but that […]

17. September 2013 at 18:26

[…] the bust too. This was a pernicious idea that took hold at the Fed in the late 1980s called “opportunistic disinflation.” It went something like this. The Fed could tighten policy to lower inflation, but that […]