Aggregate demand and the Phillips Curve

Yesterday, I did a post discussing a recent WSJ article on inflation that was partly motivated by research by James Stock and Mark Watson. They found evidence that the recent apparent flattening of the Phillips curve may reflect price stickiness in some important sectors of the economy.

The WSJ article suggested that these findings might help to explain why the Fed was having trouble hitting its inflation target. In the previous post I expressed doubt that a flatter short run Phillips curve explains why the Fed has fallen short of the 2% inflation target, although perhaps there is some model where that is an issue.

Tyler Cowen has a new post that quotes from the WSJ article. Tyler’s post is entitled:

The post begins by quoting from the WSJ article:

Recent studies have shown prices in some sectors—such as housing—do indeed rise faster when growth is in full swing, unemployment low and markets frothy. But a large chunk of the economy, from health care to durable goods, appears insensitive to rising or falling demand.

A paper published last month by economists James Stock of Harvard University and Mark Watson of Princeton University found prices accounting for nearly half of the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the personal-consumption-expenditures price index, don’t respond to changes in economic activity. In 2017 economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found such “acyclical” goods and services made up a whopping 58% of that index.

Do you see the problem? The study does not make any claims about demand being difficult to stimulate, rather the study finds evidence that demand stimulus has less short run impact on prices than one might have expected.

This is an important distinction. Are we confused because the Fed seems unable to stimulate demand, or because when the Fed does stimulate demand there seems to be little impact on prices? Those are radically different issues.

In fact, the Fed could easily boost demand with an easier monetary policy, and if they did so then inflation would increase. Because prices are sticky, the initial effect of extra demand would mostly show up in higher output, but the long run effect would be higher prices.

The Stock and Watson paper focuses on the relationship between “slack” and inflation. In my view, it’s better to focus on the relationship between NGDP growth and inflation. From that perspective, there is no mystery that needs to be explained. Inflation has been low because NGDP growth (i.e. demand) has been low. Thus from an NGDP perspective, there is little evidence that prices are insensitive to demand. We haven’t had much growth in demand.

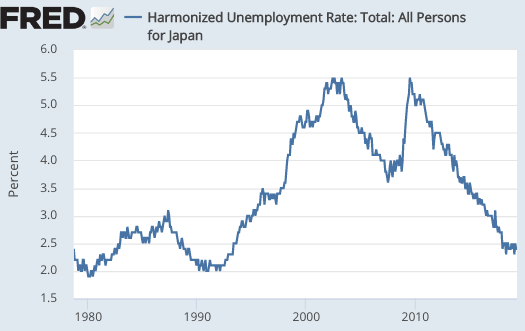

If prices appear to be insensitive to “slack”, then that’s probably because our current estimates of slack don’t track demand very closely. The currently low unemployment rate in the US does not reflect a high level of aggregate demand. Instead, it reflects a labor market that is increasingly able to reach equilibrium at low rates of NGDP growth, a situation where (as in so many other areas) Japan has been a path breaker.

PS. The OECD claims that Japan has had three recessions since 2010. I say they’ve had zero. That’s why Abe has been so popular.

Tags:

29. July 2019 at 16:47

Well, nothing in macroeconomics is ever certain, but I think this post may be correct.

There is more to the extraordinary cultural stability and social cohesion in Japan than its current economy.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there are 162 job openings for every 100 job applicants in Japan. Japan is not a nation of yellow jackets or Trumpers or Boris Johnson or AOC.

A one-bedroom apartment in Sapporo rents for $450 a month. Healthcare costs are reasonable by the standards of a developed nation, and they have bullet trains and very low crime rates.

Curiously enough, there is the equivalent of about $8,000 in yen in circulation for every resident of Japan.

I suspect a key to social stability in developed nations is very tight labor markets.

29. July 2019 at 17:05

Seems like the OECD definition of recession isn’t very useful.

29. July 2019 at 21:40

Garrett, That’s right.

29. July 2019 at 21:43

The NBER’s criteria of a recession is “”a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales”

Scott’s time frame is from 2010. A large tsnuami hit Japan in March 2011 and real GDP was -1.0, -0.4 and 1.0 annualized growth after that. Looks like a recession even if mild.

The economy was flat when Abe came to power for the second time: -01., 0.2 (elected), 0.3.

Abe assures he will raise the consumption tax so in late 2013 and 2014: -0.1, -0.9, -0.5. This was the only recession – a mild one – that occurred under Abe’s watch, which is why has been mostly popular.

29. July 2019 at 21:45

correction: in 2011 the real GDP growth rate was -1.0, -0.4 and 0.1 (not 1.0)

30. July 2019 at 02:23

BTW, one might think Japan’s labor force is shrinking,

In fact, in the latest month Japan reported its largest (formal) labor force ever.

“Japan’s unemployment rate improved to 2.3 percent in June from 2.4 percent the previous month, helped by women’s aggressive job market participation, government data showed Tuesday.

The number of people in work hit a record 67.47 million in the reporting month, with that of women topping 30 million for the first time since comparable data became available in 1953. The figures signaled the country continues to face a chronic labor shortage on the back of its rapidly aging population.”

30. July 2019 at 03:20

> Instead, it reflects a labor market that is increasingly able to reach equilibrium at low rates of NGDP growth, a situation where (as in so many other areas) Japan has been a path breaker.

Looks like that should make you more favourably disposed towards the constant nGDP per capita target that George Selgin proposes in Less Than Zero?

30. July 2019 at 04:21

Japan’s unemployment rate is low, and assuming Ben is correct, it also has the highest number of people working ever, at least formally. It also has a shrinking population whose average age is getting older. It also has a very high percentage of government debt relative to GDP. One of my hypotheses is that one way to solve the increasing debt and shrinking population problem——so the “ponzi” of increasing debt does not impoverish people_—is have a society where people continue working at an increasingly older age. I assume that is happening in Japan—-which assumes too that the real value of “social security and Medicare” payments is declining, or at least expected to.

I neither read the WSJ article or the paper it referenced—-. But Scott explicitly states we are in equilibrium at a lower rate of employment than normally is the case—which makes sense to me because we are below absolute level of working people than we have been historically at past peaks. So that alone could help explain things without resorting to a different paradigm of “lower demand than assumed” to explain lack of inflation—although I am not disputing that either.

Also, a nit question. Scott inserted the phrase “in the short run” when describing the study’s, perhaps, confused analysis on the difference between increasing demand and inflation—which Scott defuses by saying we have no, or not enough, increasing demand to cause price increases.

I wonder if the authors also were referring to “in the short run” when proposing their “a-cyclicality” sectors—-which to me seems very radical if they have evidence of that (I.e., “a-cyclicality). If they are saying prices normally rise in the short run when Demand is ‘high” —-and they think demand is high—-then showing alternative evidence that Demand is in fact not high— is very useful

30. July 2019 at 04:27

I meant lower rate of “unemployment”—2nd line, 2nd paragraph

30. July 2019 at 06:28

Pushing on a string, not a metaphor (about monetary policy) that Sumner would approve. Can monetary policy increase aggregate demand, thus growth/inflation/etc? In theory. I suppose an easier monetary policy could increase demand (lower interest rates might boost consumption while increasing debt to fund the consumption). Back to the future. But demand and inflation and all the rest must start with investment: firms invest because they expect greater demand, the investment generates higher employment, the higher employment produces the wages that generate greater demand, the higher employment and greater demand produce inflation, all all together creates economic growth (and the business cycle as we have known it). Investment is the sina qua non of the cycle.

An easier monetary policy is supposed to stimulate investment, but it hasn’t (or has barely done so) because firms aren’t confident of demand for their products. Or, in a global economy, is it that firms are confident, but confident to invest in supply chains in East Asia, the supply chains that generate big profits for firms but not higher domestic wages? While economists debate why monetary stimulus hasn’t produced the desired effect in the U.S., firms have been investing in East Asia; it’s where the profits are (not to mention tax avoidance). The problem is that the investment in East Asia has been supported by the consumption in the U.S., and now that consumption in the U.S. is lagging (because of flat wages in the U.S.), the edifice is collapsing. In the long run, the world is flat (costs, demand, etc. are essentially equal), investment will return to the US., and all is well in the kingdom. How long is the long run? Long.

30. July 2019 at 06:46

I posted a link to the Stock paper yesterday in the hopes you would talk about the fact that there are two separate questions.

1. Why does inflation remain persistently low, and which dimensions of the economy are contributing to the low inflation?

2. If we are adequately able to describe contributing sources of inflationary drags, what can be done about them.

I think you focus quite a bit on question #2, which is your monetary policy recommendations, but I don’t feel confident that we have answered #1 yet.

30. July 2019 at 06:54

I omitted the key feature of today’s monetary policy because, well, Sumner doesn’t react to it well. The key feature: using monetary stimulus to increase asset prices, the higher asset prices giving the illusion of greater wealth, the illusion of greater wealth stimulating demand, and so on. The problem is what I call the zero upper bound (to be distinguished from the zero lower bound). What’s the zero upper bound? Those in the upper tier of wealth (the upper bound), who own most of the assets, can consume just so many yachts and mansions. On the other hand, the policy has succeeded in causing inflation, inflation in the price of yachts and mansions.

30. July 2019 at 07:00

rayward, Scott and the MMs are still quantity theorists, who believe inflation happens because of excess money creation by the CB that causes higher spending through a real balance effect. Investment, consumption, and interest rates are epiphenomena in their model.

30. July 2019 at 07:02

Whether you agree with it or not, this paper by Bob Hetzel is a very good explanation for how this theory is reconcilable with interest-rate targeting central banks: https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/economic_quarterly/1993/summer/pdf/hetzel.pdf

30. July 2019 at 12:05

AD rules!

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2019/06/28/the-dynamic-as-ad-model-is-a-good-guide-to-understanding-the-economy-over-the-last-25-years-of-low-stable-inflation/

30. July 2019 at 19:30

Benjamin,

You said, “Healthcare costs [in Japan] are reasonable by the standards of a developed nation.”

Just to set the record straight. If you make more than $55k a year…

1. Your premium as a single young person are $9,000 a year.

2. You also have a 30% copay.

3. Medical treatment in Japan is incredibly stingy (hospital rooms are 8 beds to a ward with roughly 18″ between beds, no medical treatment in ambulances..transport only, delay of 8 years on average for latest life saving cancer drugs.)

31. July 2019 at 08:11

Todd, I agree that it was a technical recession. My point is that the technical definition of recession makes no sense for Japan. The definition was developed for a world of strong trend growth. Japan’s trend growth is very low, and hence random negative quarters are common. That’s very different from what people usually think of when they hear the term ‘recession’, a period of rising unemployment. I believe my definition is more useful.

Rayward, You said:

“But demand and inflation and all the rest must start with investment:”

Just stop. How much investment did Zimbabwe have during their hyperinflation? Monetary policy determines inflation.

Derrick, The answer to #1 is easy–money has been too tight. What other explanation is there? The Fed raised rates 9 times. Why do you think they did that?

Paul, I completely agree that interest rate targeting is an option, and indeed it worked OK from 1982-2007. I just don’t think it’s the best option.

31. July 2019 at 11:36

The Phillips curve hasn’t “flattened”, the Phillips curve does not exist! The correlation between inflation and unemployment does not meet statistical significance! It is bad science to talk about it as if it did.

It is time to drop bad science on the ash-heap of history.

31. July 2019 at 14:05

Doug, It’s misleading to say the Phillips curve does not exist. Rather you should say it’s not a useful model (I agree.) The Phillips curve itself is just a collection of points on a graph.