Abenomics after 5 years

Abe won a massive election victory in December 2012 on a promise of higher inflation. He was subsequently re-elected in 2014 and 2017, again by a huge margin. This sort of political success is actually very unusual in Japan, where PMs tend to come and go. It’s also unusual that he made such a big issue of inflation, in a country full of elderly savers. (So much for armchair public choice theory.) So how’s he doing after 5 years, apart from being highly popular?

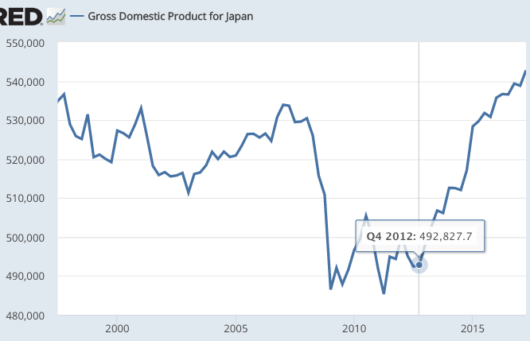

The most important impact of Abenomics was on NGDP, which had been trending downwards prior to his election:

It’s actually better than this Fred graph shows, as Q2 NGDP was revised up to 544.9 trillion yen, and the third quarter came in at a very strong 549.2 yen.

It’s actually better than this Fred graph shows, as Q2 NGDP was revised up to 544.9 trillion yen, and the third quarter came in at a very strong 549.2 yen.

According to market monetarist theory, strong NGDP can be useful in solving 2 problems, excessive debt burdens and high cyclical unemployment. Abenomics has been very successful on both fronts. Unemployment had fallen to 2.7%, the lowest level in 23 years. And the public debt to GDP ratio has leveled off, after soaring higher at a dangerous rate in recent decades.

The debt ratio achievement is especially impressive given the extremely unfavorable demographics facing Japan:

Normally a rapidly falling population makes the debt situation worse, and also makes it more difficult to boost NGDP. Abe overcome this obstacle on both fronts. The boost to NGDP also occurred during a period of fiscal austerity, which of course contradicts the Keynesian model.

Normally a rapidly falling population makes the debt situation worse, and also makes it more difficult to boost NGDP. Abe overcome this obstacle on both fronts. The boost to NGDP also occurred during a period of fiscal austerity, which of course contradicts the Keynesian model.

The BOJ has an inflation target of 2%, and this is one area where they have fallen somewhat short. Prices are up about 5% in five years, which is certainly better than the deflation that preceded Abenomics, but well short of success:

Don’t pay too much attention to the year-to-year changes, as the inflation rate in 2014 was boosted by a sales tax increase, and the inflation rate after 2014 was held down by plunging oil prices. Most forecasters see an inflation rate of just under 1% going forward. Over at Econlog I explain why that’s still too low, even though the Japanese economy can do fine with 1% inflation.

To summarize:

1. NGDP was a big success

2. The debt situation is dramatically improved.

3. The labor market is far stronger

4. Inflation is higher, but well short of the 2% target.

I’d say that Abenomics deserves a B+ on monetary policy. I don’t know enough to comment on the other aspects of his policy, although obviously I don’t agree with his nationalism.

PS. I’d like to thank Ralph Benko for his very generous comments in Forbes. I still feel pretty good about the prediction I made in “An Even Greater Moderation”, which he links to.

Tags:

29. December 2017 at 17:54

Great piece in Forbes. I have only one question. Do enough of the right sort of economists read Forbes?

29. December 2017 at 18:51

Lorenzo, No.

29. December 2017 at 19:02

At least one person of the Abe’s brains has said “NGDPLT is attractive”.

Next year,new BOJ head will be appointed.

29. December 2017 at 20:06

I’m pretty bearish about the next years. I expect that the decline of Trump will coincide with a relevant economic downturn. But I’m happy if I’m wrong and Scott is right.

29. December 2017 at 20:16

Is anyone confused by the Q1 2015 – Q3 2015 jump in nominal GDP. Supposedly it rose 24 trillion yen in 6 months. This never made sense to me. It appears to be a result of the consumption tax increase YoY effect ending.

Scott, I’d point to a few reasons why Abenomics (more like Kurodanomics) has succeeded:

1. Real Japanese Currency value fell 40% to 1975 levels from Q3 2012. Now they are more competitive with Chinese and Korean producers.

2. This extreme depreciation led directly to a massive tourist boom. Now Japanese get to see millions of random people clogging up their highways, temples, and streets. But hey, GDP is what matters and beggars can’t be choosers.

3. China’s economy is almost twice the size it was in 2012 (in real terms). China imports about 80% more Japanese goods and services today. That has been a huge boost.

4. Real labor costs in Japan are down about 15% since 2012. Japanese wages are growing less than inflation rises. Maybe that drops unemployment; but it explains why corporations have record profits while average Japanese have no children.

Japan essentially devalued internally and externally. And because Japanese don’t flee with their capital, the economy benefited. Other nations might not be so lucky.

29. December 2017 at 20:27

Nice post, and Haruhiko Kuroda, BoJ Governor, is in a class of his own as far central bankers go.

It is worthwhile to remember that the lone developed economy to largely sidestep the Great Depression was Japan, thanks to its finance minister Takahashi Korekiyo. You would think the lesson of Japan in the Great Depression would be central to macro textbooks, but instead the historical lesson is largely lost.

Why learn, when hubris is so much more fulfilling?

One deflation “problem” they have in Japan today is that in the still-growing city of Tokyo there is plenty of property development, So much so that housing costs are flat and office rents are expected to start declining,

The Nikkei 225 is up 21.3% YOY.

There are more job opening than people looking for work in Japan, by most measures. (There is some confusion about part-time workers).

Japan is becoming the nicest place in the world to live.

Just one survey, but Monocle rates Tokyo the world’s best big city.

https://www.wien.gv.at/english/politics/international/competition/monocle-quality-of-life-survey.html

Tokyo is affordable housing, safe streets, good schools, excellent mass transit, great eating, culture galore.

I would say US economists and policy-pundits should travel to Japan not to lecture and advise, but to study and learn.

30. December 2017 at 16:09

Alec, Don’t confuse symptoms and causes. Monetary stimulus is the cause–currency depreciation is the symptom.

1. January 2018 at 02:47

Many thanks for the post, Scott. Spot on.

As a side issue, while Abe may be a nationalist, I think he has been accommodating of other political preferences both within his party, which includes liberal dynasties such as Kono’s (whose father as PM issued the first official apology for the war-time abuse of women and was an early supporter of immigration of loosening of citizenship laws) as well as the general public. For instance, even though his coalition has an all-commanding supermajority, he does seek common ground with the opposition on constitutional reform.

His proposal for constitutional amendment is to keep the War-Renouncing Article 9 as is, and merely add a mention the existence of the Self-Defense Forces – which is largely the Constitutional status quo of the past 60 years. In short, he is only asking the opposition to accept reality as we know it, rather than change anything big.

As a reminder, Japan has renounced “the sovereign right of a nation to wage war” and the existing constitutional interpretation is that this right applies to aggressive war, but not to the right to defend yourself when attacked, or to help defend those who come to your help when attacked. The last bit, about defending allies, is new – and introduced at request of the US.

Personally, I prefer a nationalist who is capable and willing to seek moderate, pragmatic, common ground on important national matters, to politicians who win narrow pluralities and push their partisan preferences at all costs and divide their nations.

That said, I don’t like nationalism either.

1. January 2018 at 08:24

Mikio, Excellent comment–that makes sense. You are certainly better informed on these issues than I am.

1. January 2018 at 09:42

“I prefer a nationalist who is capable and willing to seek moderate, pragmatic, common ground on important national matters, to politicians who win narrow pluralities and push their partisan preferences at all costs and divide their nations.”

Isn’t it the Japanese way, culturally, to seek consensus?

1. January 2018 at 16:51

Anon,

Yes, that is true. However, there is wiggle room within the culture – just like there is room for rational compromise within a Western “invididualist” / “confrontational” culture.

My point is, within the context of his culture, Abe is choosing to deploy his overwhelming political mandate to push for non-consensual action in some areas, to get things done, and less so in others.

Specifically, he has used his “partisan” power in areas that are not traditionally “nationalist” by nature, namely when he pushed for Kuroda regime change at the BOJ, and when he strong-armed the agriculture sector (base of his party) to accept the market opening under the TPP and the deal with the EU.

By contrast, in the “nationalist” policy areas (defense, veneration of the war dead), he is mindful of the opposition at home and abroad.

That’s why I think the label “nationalist,” while not wrong, isn’t really fair. His policies are actually more open-minded and internationalist than those of many predecessors who weren’t labeled as such.

1. January 2018 at 21:59

On Dec. 22 the Fed release a study that concludes:

“Rent burdens (for low income US households) have increased over the past 15 years, due to both increasing rents and decreasing incomes.”

I would have guessed incomes were about flat over that period but the Fed says they are going down.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/assessing-the-severity-of-rent-burden-on-low-income-families-20171222.htm

1. January 2018 at 22:06

rental income with capital adjustment

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RENTIN

skyrockets dude

2. January 2018 at 03:03

Thank you for your nice blog of Abenomics.

I tend to agree to your positive four comments on Abenomics in your blog.

I am not sure, however, if permanent and excessive monetary expansion could make a great sense in Japan any more.

In particular, the BOJ’s asset or debt size now stands at about 519 trillion yen. It is clear the BOJ would hit the entire size of the economy (about 539 trillion yen) very soon, given the slow growth of the NGDP and the rapid pace of the BOJ’s monetary expansion.

The BOJ could be forced to normalize its currently very expansionary monetary policy, sooner or later. For instance, a Taylor-rule suggests that the Bank’s policy interest rate should now be raised to 0.5% from -0.1%, given 0.2% core CPI inflation and 0.5% positive output gap based on latest OECD data.

My back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the Japan’s central bank could suffer from huge loss, amounting to about 40 trillion yen (about 8% of the NGDP), assuming 1% rate of inflation, and 1% nominal interest rate (could be 3% given 2% inflation target) with the bank’s holding of long term government debt amounting to 400 trillion yen, and with average 10 year duration (i.e. 40 trillion yen = 400 trillion x 10years x 1% rise of interest rate).

Such large rises of both rates of inflation and interest, if and when being materialized, could become not only politically unacceptable but economically catastrophic.

Furthermore with continued excessive monetary expansion, the size of the BOJ’s balance sheet could explode, and given the scheduled downsizing of the FRB’s balance sheet, the dollar-yen exchange rate could also skyrocket from current 112 yen to about 150 yen by the end of 2018, in accordance with the so-called Solos formula by dividing the expected size of the BOJ by the scheduled size of the FRB.

In sum. I tend to agree with your positive four summaries on Abenomics. However, policies endlessly using monetary measures alone might generate not small side effects on to not only Japan’s economy buy also the world economy as well.

Best regards,

Tomo Nakamaru

An Ex-World Banker

2. January 2018 at 08:05

It seems churlish to disagree – we’d all love ‘Abenomics’ actually to be a ‘thing’. And, of course, nominal GDP is the key metric in Japan. But you really do need to accept a couple of things:

First, to the extent that GDP growth has been led by investment spending, it has been only just barely enough to cover depreciation charges during the period – ie, capital stock has been virtually unchanged despite the rise in return on capital.

Second, if you look at the source of profits during the last couple of years (using a Kaleckian disaggregation), the plain fact is that between 2014 and 2016 the profits rise was primarily the result of an improving trade position – plausibly a longer-term result of the weakening of the yen.

Third, that has changed very sharply during the last year, with profits growth being attributable now to practically nothing but Abe’s willingness to blow out the budget deficit prior to his election.

Meanwhile, to the extent that ‘Abenomics’ aspired to free/discover new sources of domestic demand, it has failed – the proportion of profits attributable to {consumption minus compensation} has been falling consistently since the end of 2013!

2. January 2018 at 11:09

Sorry, bu tas you can see in https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/government-debt-to-gdp

The government debt/GDP hasn’t decrease. In fact in 2016 it has reached the all times record of 250%.

2. January 2018 at 11:20

Tomo, You have things backwards. A far more expansionary monetary policy would lead to higher inflation, higher nominal interest rates, and a far lower ratio of base money to GDP. Thus the balance sheet has been large because policy is too contractionary.

I know that’s counterintuitive, but the data strongly support this claim. The higher the trend rate of inflation, the smaller the central bank balance sheet. Neither the monetary base nor interest rates tell us anything useful about the stance of monetary policy.

Michael, Tell why why I should care about Japanese corporate profits.

Miguel, Thanks for providing a graph confirming what I said:

“And the public debt to GDP ratio has leveled off, after soaring higher at a dangerous rate in recent decades.”

2. January 2018 at 16:42

Tomo-

If rates of inflation in Japan remain near zero, why do you define monetary policy as very expansionary?

As for central bank losses on balance sheets, are not those something of a legal or accounting fiction? A central-bank prints money to acquire assets. I wish to endure such losses.

New topic: would Japan and the Bank of Japan be better advised simply to move to helicopter drops?

2. January 2018 at 18:28

Your last graph shows all of the “success” in creating inflation occurred in the first 18 months of Abe’s tenure. Since then, inflation is essentially zero, certainly not close to Abe’s target.

“And the public debt to GDP ratio has leveled off, after soaring higher at a dangerous rate in recent decades.”

In other words, you’re creating 250 yen in debt for every 100 yen in GDP. That’s not a situation to celebrate, even if it is an improvement.

2. January 2018 at 18:55

Scott

I think You were right about Abe’s nationalism.

Mikio

You are obviously quite biased on the nationalism issue. It is understandable because you are of Japanese origin. But please no gaslighting of non-Japanese speakers (I am usually peeved about these things because I see it all the time as a Japanese speaker myself). “Mindful of opposition”? I mean come on….so in Japan being mindful means publicly insulting the descendants of WWII victims by paying visits to a shrine housing class A war criminals? Or systematically downplaying the sex slave issue during WWII? Revising history books?

2. January 2018 at 21:25

Brian, You said:

“Your last graph shows all of the “success” in creating inflation occurred in the first 18 months of Abe’s tenure. Since then, inflation is essentially zero, certainly not close to Abe’s target.”

I guess you didn’t read the post to the end. I addressed that issue.

You said:

“That’s not a situation to celebrate, even if it is an improvement.”

It’s a huge improvement. As I said, they need to do more. But things are better than before Abenomics.

3. January 2018 at 21:00

You said “I addressed that issue.” Not really. You said “Inflation is higher, but well short of the 2% target,” when inflation is nearly zero as it was for the decade before Abe’s first election. It looks an awful lot like Abenomics was only good for a one-shot price increase. The NGDP growth also loses some luster when you consider that Abe has consistently been running deficits of about 4% of GDP.

Mikio, the reason Abe has had to go slowly on his Constitutional revision is that he simply lacks support. Revision requires approval by a majority of voters in a referendum, and despite the large majorities his LDP-KP governments have had, none of them have ever won half of the vote in an election. (Also, Komeito would never support revision of Article 9.)

3. January 2018 at 21:03

Benjamin Cole should know better than to praise Japan’s economic performance during the 1930s, unless he approves of how it happened: by building up the military and launching wars against Manchuria/ Manchukuo and the rest of China. It was the same military Keynesianism employed by Hitler… and met the same end in 1945.

4. January 2018 at 07:09

Brian J. —

Yes, it was the militarists who in 1936 assassinated Takahashi Korekiyo, the most brilliant central banker of all time.

Takahashi’s helicopter drops worked. But he was only a finance minister and not in charge of the way the government spent money.

Takahashi had nothing to do with Japan’s horrific imperialism. Ben Bernanke financed Iraqistan?

Arthur Burns provided the bucks for Vietnam?

4. January 2018 at 07:47

Benjamin is absolutely correct. In fact, Takahashi primarily tried to target excessive military spending to address strong inflationary pressures, and he was well-known for strongly disliking the rapid ascent of militarists within the army. He explicitly advocated “rich country, prosperous people”, which is a slightly subversive tweak in the Meiji slogan “rich country, strong army”. This is why he was targeted by militarists in their 1936 coup attempt.

He is a genuine hero in my opinion, and his brilliant reflationary (or shall I say “symmetric”) policy certainly had nothing to do with Japan’s hard turn toward militarism in the subsequent period.

4. January 2018 at 17:54

The topic of Takahashi, and a recent post on Italy in Econlog, raise a fascinating question. Maybe Scott Sumner will address it.

The thrust of the Econlog post is that in democracies people want freebies, and so the state borrows money to meet demands, and does not tax enough. See Italy, Greece, and even the US (did we pay-as-you-go on the Iraqistan follies? A 10% surcharge on your tax bill?).

Okay, so in democracies, national debts will spiral up. You have to be Teutonic to avoid it, as most people are not Teutonic. Gee, present-tense America anyone? Trumpian tax cuts, but no spending cuts? Yahoo!

That brings me to helicopter drops. Usually helicopter drops are dismissed not as ineffective (most macroeconomists seem to think they will work, and did in fact work in depression-era Japan) but that soon pols will going to excess on helicopter drops. “Yes I want to print money and build a new post office in my district, give poor people housing, or have the avionics for that new fighter-jet made in my state.”

But, in the real world of democracies, it appears the choice is between a) mounting debts (see Western democracies ) or b) helicopter drops. Fiscal responsibility? Not a choice. You can choose a) or b).

Adair Turner suggests “helicopter drops on a leash,” perhaps drops limited to some percent of GNI or GDP, could work.

Or would you prefer to hand your children mounting and onerous debts?

Worthy topic for illumination and debate.

Add on: I sense the global economy is moving into a new zone, that might require constant demand amendments by the state actors. For some reason, globally, people are saving too much, and chronically. They save even when rates go to zero. Global gluts of capital. As the world gets richer, this problem may get worse. Every global industry is glutted with supply. Think autos.

But expanding state programs is a bad idea.

So I say, just tax much less, and finance the difference with helicopter drops. Try funding Social Security through helicopter drops, for example, thus cutting taxes on people who work and employ.

Add on, add on: Scott Sumner’s recent Econlog post on housing is correct.

5. January 2018 at 17:54

I discuss Japan and helicopter drops here:

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2018/01/05/choice-ever-mounting-national-debts-central-bank-helicopter-drops/

5. January 2018 at 21:48

African-American unemployment hits lowest rate in history

http://archive.is/9UHsy

6. January 2018 at 12:07

Brian, read the post again. And again. And keep reading it until you get the part that addresses the issue you raised.

7. January 2018 at 11:33

@Benjamin Cole

But, in the real world of democracies, it appears the choice is between a) mounting debts (see Western democracies ) or b) helicopter drops. Fiscal responsibility? Not a choice. You can choose a) or b).

Helicopter drops would be just another entitlement. What’s the history of entitlements again? Why do you even think they wouldn’t do both? There’s no rule in your approach that prevents that we won’t end up with both. And of course we would end up with both.

7. January 2018 at 16:44

Christian:

Adair Turner suggests “helicopter drops on a leash.” A rule limiting drops to some ratio of GDP etc.

Another approach would be to simply ban national borrowing, and go to helicopter drops by default. This would prevent the use of both borrowing and dropping.

Beyond that, the current nexus between fiscal and monetary policy is hopelessly confused. We have a Fed engaged in QE or reverse repos or balance sheet tapering or other mysterious open-market operations.

Michael Woodford says that QE in combination with federal deficits is in fact a helicopter drop. There is further confusion, ala David Beckworth, that unless QE is permanent it is not a helicopter drop.

Got that?

There is no clarity and little transparency in our major macro economic policymaking.

Helicopter drops are clear and aboveboard.

8. January 2018 at 06:34

Add on to anyone who might be reading:

Balanced US federal budgets ever again?

Think about this: We have a GOP Congress, and the second-longest running economic expansion in US history (and still going), and the highest corporate profits ever (absolutely and relative to GDP), and a 17-year low in unemployment.

The GOP just voted to add a couple trillion in additional fresh debt on the already accumulating federal debt.

If the GOP does not balance the federal budget now, when would they? It doesn’t get any better than this.

The last GOP president who balanced the federal budget was……….Eisenhower.

The Dems are worse (excepting Bill Clinton).

So…when you pontificate about monetary policy, please premise your comments with, “Since the Congress will always run large federal deficits…..”

If we can replace deficits with helicopter drops….is some inflation better than a bankrupt nation?

Washington as Athens on the Potomac…but not in the way we imagined…..

8. January 2018 at 12:00

Scott,

OT a bit, here’s a nice panel discussion at Brookings on whether to stick to the 2% inflation target:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1BZh1cZ_-4

8. January 2018 at 12:00

Should say that Mishkin and Bernanke are panelists.

8. January 2018 at 16:21

@Benjamin Cole

I agree in so far that the lines (of QE) seem to get blurry when it involves corporate bonds and so on. I don’t really get it. Scott seems to get it but I don’t.

8. January 2018 at 16:41

Christian: don’t worry. No one else understands monetary policy either.

8. January 2018 at 17:47

[…] Abenomics after 5 years http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=32764 […]

8. January 2018 at 22:13

[…] Scott Sumner at The Money Illusion agrees that the most important impact of Abenomics was on Nominal GDP, which had been trending downwards prior to Abe’s election. According to market monetarist theory, strong NGDP can be useful in solving two problems: excessive debt burdens and high cyclical unemployment. Abenomics has been very successful on both fronts. Unemployment had fallen to 2.7%, the lowest level in 23 years; and the ratio of public debt to GDP has leveled off, after soaring higher at a dangerous rate in recent decades. Prices are up over the past five years, and certainly better than the deflation that preceded Abenomics, but well short of the 2% target (Figure 2). […]

9. January 2018 at 15:47

Here is the Brookings event now broken up into 4 parts:

Part 1:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V8hgP4qQoLA&t=1560s

Part 2:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFrJLrm0tQE

Part 3:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHtxTwTGDAM

Part 4:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYiyt_K10LE

Note that in part 4, Larry Summers endorses NGDP targeting.

9. January 2018 at 15:48

Sorry, scratch that last note. I meant to type that Summers endorses NGDP targeting in part 1, at roughly the 25 minute mark.

9. January 2018 at 17:14

North Korea and South Korea, now at the negotiating table:

https://i.imgur.com/0Jaly3p.jpg

11. January 2018 at 01:46

“China is reportedly thinking of halting US Treasury purchases and that’s worrying markets

The report notes that Chinese officials think U.S. debt is becoming less attractive compared with other assets.

Trade tensions between the two countries could provide a reason to slow down or halt the purchases, according to the report.

Treasurys and the dollar fell on the report. Gold rose. Equities fell

China is the biggest buyer of U.S. sovereign debt.”

–30–

The experts say yields will rise, and note huge financing needs ahead. For some reason, saying the US should balance its budget is not a thing anymore.

The wags ask, “So why is the Fed selling its bond portfolio?”

11. January 2018 at 14:32

The BoJ announced that it will (effectively) begin tightening monetary policy.

Most likely that won’t cause a big change just yet because the change was more out of necessity (running out of bonds to purchase).

Please correct me if I am wrong.

http://mobile.reuters.com/article/amp/idUSKBN1EY0FF

11. January 2018 at 16:38

Alec,

Should the BoJ buy bonds from other nations? Why or why not?

23. April 2018 at 23:27

[…] Abenomics After 5-Years by Scott Sumner via Econolog […]

23. April 2018 at 23:56

[…] Abenomics After 5-Years by Scott Sumner via Econolog […]