Endogenous interest rates and aggregate demand

I’m still trying to figure out the MMT view of monetary policy. It’s not easy for me, because MMTers seem to think that “monetary policy ” and “changes in interest rates” are pretty much the same thing. I view that as reasoning from a price change, but even some conventional economists make that mistake.

For a brief moment on page 406 of Macroeconomics (by Mitchell, Wray and Watts) it seemed like they understood this distinction:

In a growing economy, it is likely that aggregate demand conditions will improve at times when the market rate of interest rises as the central bank often raises its target rate in an expansion.

Yes! Interest rates are largely endogenous, mostly reflecting changes in output and inflation expectations. When the economy is booming and/or inflation is rising, then market interest rates will also tend to increase. My only quibble is that the authors need not have added, “as the central bank often raises its target rate in an expansion”, as this relationship is true even in an economy that doesn’t have a central bank (say the US prior to 1913.)

But that minor quibble contains the seeds of a major problem, as I don’t know if MMTers even recognize the income and Fisher effects. At times they seem to assume that all changes in interest rates are “monetary policy”, i.e. the liquidity effect.

MWW continue:

[W]e would not observe investment falling when the market interest rate rose because the IRR of each project could also be increasing

So far so good. The internal rate of return will rise with inflation and/or output growth. But then this:

Thus, it is important to avoid applying a mechanical interpretation of the concept of the [Marginal Efficiency of Capital]. Keynes, in fact, did not think investment would be very responsive to changes in the market rate of interest, especially when the economy was in recession or boom.

Woah! The term “Thus” is mixing up two unrelated issues. First, the fact that because interest rates are largely endogenous you often observe interest rates move procyclically. The second (and more dubious) claim is that this is evidence that the economy is not very responsive to interest rate changes. But that doesn’t follow at all. As an analogy, it is true that budget deficits are usually high when the economy is very weak, but even a monetarist like me would never argue that this proves that exogenous increases in deficit spending are contractionary.

In fact, if interest rates decline due to a highly expansionary monetary policy, then it will have a big impact on aggregate demand. On the other hand, if interest rates decline due to the income and/or Fisher effect, then you should not expect an expansionary impact.

In mainstream economics, this can all be easily explained by referring to the gap between the target interest rate and the natural interest rate. But I’m told that MMTers don’t believe the natural interest rate matters, or they think it’s always zero, or something. (BTW, Do they think the real or nominal natural interest rate is zero?)

On the next page (407):

The extreme optimism that typically accompanies a boom also would reduce the sensitivity of investment to changes in the market rate of interest. With high expected returns, firms would be prepared to pay higher borrowing costs.

That seems to confuse shifts in the MEC with changes in the elasticity of demand for investment (as a function of interest rates), unless I’m misinterpreting their claim. The fact that interest rates are higher during a boom doesn’t mean that investment is less sensitive to changes in interest rates.

On page 464, you can see where MMTers’ confused ideas about endogeniety cause them to really go off the rails:

The fact that the money supply is endogenously determined means that the LM schedule will be horizontal at the policy interest rate. All shifts in the interest rates are thus set by the central bank and funds are supplied elastically at that rate in response to the demand. In this case, shifts in the IS curve would not impact on interest rates. From a policy perspective this means the simple notion that the central bank can solve unemployment by increasing the money supply is flawed.

No, no, a thousand times no!!! The final two sentences absolutely do not follow from the first two sentences, which leads me to believe that MMTers misunderstand the concept of endogeniety.

It’s cheating to claim the money supply is “endogenous” and then completely ignore the fact that the interest rate is also endogenous. In the second sentence they mention that central banks “shift” the interest rate. Yes they do, and they do so to prevent shifts in the IS curve from destabilizing the economy. As a result, shifts in the IS curve absolutely do impact interest rates. A rightward shift in the IS curve right after Trump was elected caused interest rates to go up. I could cite 1000 similar examples. Central banks are like the child that runs out in front of a parade and then has the delusion that he is determining the route of the parade.

So the third sentence is wrong; IS shocks do affect interest rates. But the fourth sentence is even worse. The facts cited in the first two sentences absolutely do not imply that the central bank can’t address unemployment by increasing the money supply.

Go back to the late 1970s or the early 1980s, when interest rates were in the 10% to 15% range. Does anyone seriously believe that a huge increase in the money supply would have failed to boost employment, at least until sticky wages caught up?

MMTers would say a big increase in the money supply is impossible because it would push interest rates to zero. But that completely misses the point. Let’s say the Fed just increased the money supply enough to push rates from 12% to 2%. Does that not boost employment?

Another argument I’ve heard is that lower rates don’t matter because interest payments are a zero sum game. Some people pay less interest but others earn less interest. Yes, they may not matter for consumption in a simple Keynesian cross model, but they certainly do matter for investment, even in the simple Keynesian model. Of course I think that the Keynesian cross model is wrong, but excess cash balances also drive NGDP in the monetarist model, so either way (exogenous and permanent) money creation is expansionary, at least when rates are positive (and in reality even when they are zero.)

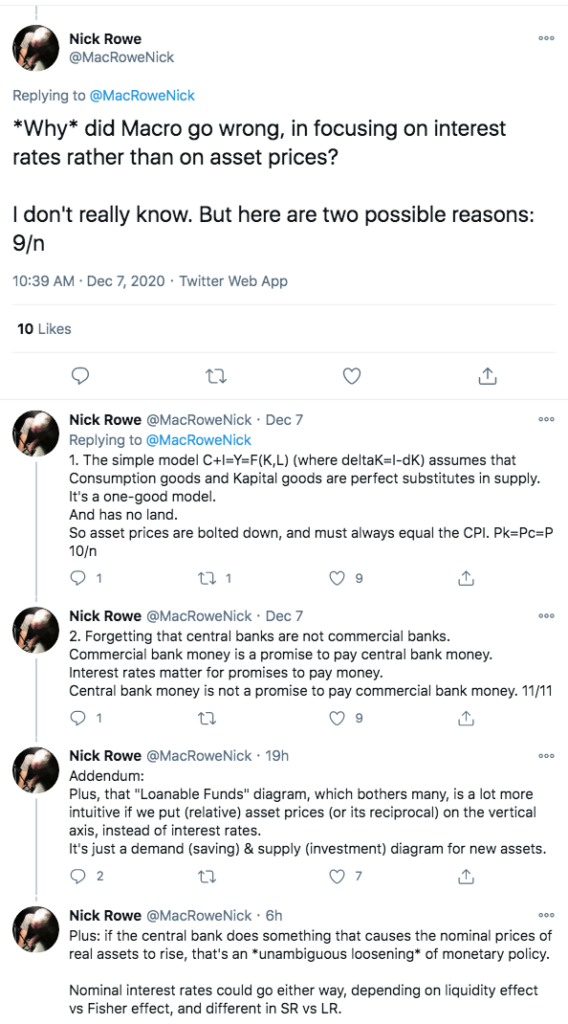

Just to be clear, I don’t agree with the Keynesian view that easy money lowers interest rates, nor do I agree with the NeoFisherian view that easy money raises interest rates. Both are reasoning from a price change. But even using the flawed Keynesian model (where easy money lowers interest rates), the MMT people are mistaken about endogenous money, unless I’m missing something. And after three weeks of arguing with commenters, I’m finding it harder and harder to imagine that I’ve missed some brilliant MMT insight that explains all of this.

Because they get monetary policy wrong, they also get fiscal policy wrong. Thus on page 506 we are told that one reason why “fiscal deficits do not place upward pressure on interest rates” is because “The official interest rate is set by the central bank”.

Thus in the MMT world, the interest rate is not subject to macroeconomic shocks like other macro variables, it’s just an arbitrary number set by the central bank. IS shocks and fiscal stimulus don’t raise rates because the rates are set by the central bank. And the central bank has no discretion to change the money supply, because doing so would cause interest rates to change. And that would be bad because . . .

Again, I don’t believe “endogenous” means what MMTers think it means.

PS. I have a related critique of MMT over at Econlog.