Here’s Nick Rowe:

I understand how monetary policy would work in that imaginary Canada (at least, I think I do). Increasing the quantity of money (holding the interest rate paid on money constant) shifts the LM curve to the right/down. Increasing the rate of interest paid on holding money (holding the quantity of money constant) shifts the LM curve left/up. Done.

It’s a crude model of an artificial economy. But it’s a helluva lot better than a simple New Keynesian model where money (allegedly) does not exist and the central bank (somehow) sets “the” nominal interest rate (on what?).

I think this is right. But readers might want more information. Exactly what goes wrong if you ignore money, and just focus on interest rates? Let’s create a simple model of NGDP determination, where i is the market interest rate and IOR is the rate paid on base money:

MB x V(i – IOR) = NGDP

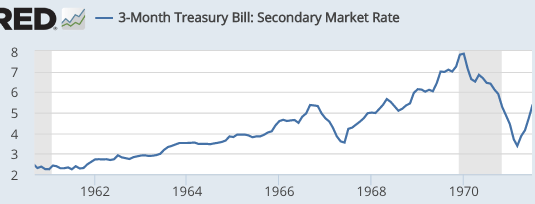

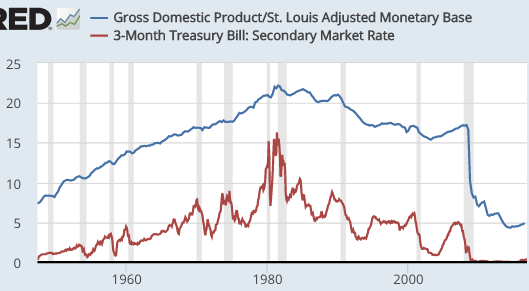

In plain English, NGDP is precisely equal to the monetary base time base velocity, and base velocity depends on the difference between market interest rates and the rate of interest on reserves, among other things. To make things simple, I’m going to assume IOR equals zero, and use real world examples from the period where that was the case. Keep in mind that velocity also depends on other factors, such as technology, reserve requirements, etc., etc. The following graph shows that nominal interest rates (red) are positively correlated with base velocity (blue), but the correlation is far from perfect.

[After 2008, the opportunity cost of holding reserves (i – IOR) was slightly lower than shown on the graph, but not much different.]

What can we learn from this model?

1. Ceteris paribus, an increase in the base tends to increase NGDP.

2. Ceteris paribus, an increase in the nominal interest rate (i) tends to increase NGDP.

Of course, Keynesians often argue that an increase in interest rates is contractionary. Why do they say this? If asked, they’d probably defend the assertion as follows:

“When I say higher interest rates are contractionary, I mean higher rates that are caused by the Fed. And that requires either a cut in the monetary base, or an increase in IOR. In either case the direct effect of the monetary action on the base or IOR is more contractionary than the indirect effect of higher market rates on velocity is expansionary.”

And that’s true, but there’s still a problem here. When looking at real world data, they often focus on the interest rate and then ignore what’s going on with the money supply—and that gets them into trouble. Here are three examples of “bad Keynesian analysis”:

1. Keynesians tended to assume that the Fed was easing policy between August 2007 and May 2008, because they cut interest rates from 5.25% to 2%. But we’ve already seen that a cut in interest rates is contractionary, ceteris paribus. To claim it’s expansionary, they’d have to show that it was accompanied by an increase in the monetary base. But it was not—the base did not increase—hence the action was contractionary. That’s a really serious mistake.

2. Between October 1929 and October 1930, the Fed reduced short-term rates from 6.0% to 2.5%. Keynesians (or their equivalent back then) assumed monetary policy was expansionary. But in fact the reduction in interest rates was contractionary. Even worse, the monetary base also declined, by 7.2%. NGDP decline even more sharply, as it was pushed lower by both declining MB and falling interest rates. That’s a really serious mistake.

3. During the 1972-81 period, the monetary base growth rate soared much higher than usual. This caused higher inflation and higher nominal interest rates, which caused base velocity to also rise, as you can see on the graph above. Keynesians wrongly assumed that higher interest rates were a tight money policy, particularly during 1979-81. But in fact it was easy money, with NGDP growth peaking at 19.2% in a six-month period during late 1980 and early 1981. That was a really serious error.

To summarize, looking at monetary policy in terms of interest rates isn’t just wrong, it’s a serious error that has caused great damage to our economy. We need to stop talking about the stance of policy in terms of interest rates, and instead focus on M*V expectations, i.e. nominal GDP growth expectations. Only then can we avoid the sorts of policy errors that created the Great Depression, the Great Inflation and the Great Recession.

PS. Of course Neo-Fisherians make the opposite mistake, forgetting that a rise in interest rates is often accompanied by a fall in the money supply, and hence one cannot assume that higher interest rates are easier money. Both Keynesians and Neo-Fisherians tend to “reason from a price change”, ignoring the thing that caused the price change. The only difference is that they implicitly make the opposite assumption about what’s going on in the background with the money supply. Although the Neo-Fisherian model is widely viewed as less prestigious than the Keynesian model, it’s actually a less egregious example of reasoning from a price change, as higher market interest rates really are expansionary, ceteris paribus.

PPS. Monetary policy is central bank actions that impact the supply and demand for base money. In the past they impacted the supply through OMOs and discount loans, and the demand through reserve requirements. Since 2008 they also impact demand through changes in IOR. Thus they have 4 basic policy tools, two for base supply and two for base demand.

PPPS. Today interest rates and IOR often move almost one for one, so the analysis is less clear. Another complication is that IOR is paid on reserves, but not currency. Higher rates in 2017 might be expected to boost currency velocity, but not reserve velocity. And of course we don’t know what will happen to the size of the base in 2017.