It’s weeks like these that clearly expose that the world’s central banks are still living in the 20th century—the world of long data lags for GDP and crude Keynesian models. Eventually they will arrive in the 21st century, and it will all be about asset prices.

One problem is what might be called “central banker hours”. Even when they make a serious error, they don’t bother to correct it until much later. Partly because they meet only once every six weeks (and why is that?), and partly because they don’t like to admit errors.

In a better world the risk of recession and the risk of the economy overheating would always be evenly balanced. And I mean always, every single day of the year. Does it sound like the risks are balanced today?

As the global economy falters, sapping demand for everything from consumer electronics to cars to commodities, investors are anxiously awaiting surveys on the services sector in China and the Unites States – the world’s biggest two economies – due later in the day.

If we hooked Janet Yellen and Stanley Fischer up to a lie detection machine, do you think that in their heart of hearts they are equally worried about a recession and a 1960s-style inflationary boom in the near future?

Or how about 10-year bond yields plummeting to 1.83%, from about 2.2% when they “raised” interest rates in December. I hope all you Austrians who whined about “artifically low rates” being set by the Fed are pleased to have gotten your way.

In a better world our central bankers would not tell us that a 0.5% interest rate is “still very accommodative”, when our intro to money textbooks tell us that low interest rates do not mean money is accommodative. Here’s Mishkin’s textbook:

1. It is dangerous always to associate the easing or the tightening of monetary policy with a fall or a rise in short-term nominal interest rates.

2. Other asset prices besides those on short-term debt instruments contain important information about the stance of monetary policy because they are important elements in various monetary policy transmission mechanisms.

I expect more than EC101 errors from the elite economists at the Fed.

In a better world the Fed, ECB, BoE and BOJ would not wait six weeks. They’d get together next week to discuss a coordinated plan to reflate the global economy. Just the announcement of such a meeting would do wonders.

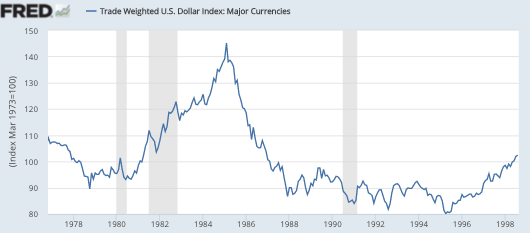

In a better world the Fed would not raise rates after a year of 2.9% NGDP growth, and then mumble something about a “strong dollar” hurting manufacturing. Gee, I wonder why the dollar is so “strong”?

In a better world the Fed would not try to arrogantly tell the markets where rates should be, but rather would meekly take its marching orders from the markets. In other words, I don’t agree with Tyler:

If I were at the Fed, I would consider a “dare” quarter point increase just to show the world that zero short rates are not considered necessary for prosperity and stability. Arguably that could lower the risk premium and boost confidence by signaling some private information from the Fed.

I’m increasing doubtful of the view that the Fed knows something the markets don’t and increasingly accepting of the exact opposite view.

In a better world the Fed would take off its blindfold, and create and subsidize NGDP, RGDP, and unemployment rate prediction markets.

In a better world we’d have level targeting.

In a better world the people who argued for a rate increase would not assume that it’s necessarily the first step toward pushing rates higher one, two, and three years in the future. Instead they would understand that a more expansionary monetary policy would be a better way to promote durably higher rates.

In a better world people would not ask how a measly 1/4% interest rate increase could have major effects, they’d understand that interest rates are not monetary policy, and that a huge change in the stance of monetary policy might be accompanied by a tiny change in interest rates. Recall the US in 1937, the ECB in 2008, and the ECB in 2011, all tiny increases in interest rates, all accompanied by much tighter monetary policy.

PS. I added election odds to the “Sites I Visit” at right, for you political junkies. As I predicted late last night, Rubio surged higher. Indeed he surged by much more than I expected, and is now the strong favorite to win the nomination. Of course Hillary Clinton is still the most likely to win the election.

PPS. Tomorrow we finally cut the cord, so if you are someone who knows me then throw away the phone number. In a better world I would not have to pick up the phone every 15 minutes to deal with telemarketers who ignore the fact that I’m on the do not call list, and then have to tell them what I think of their operation. From now on, cell phone and email are the only way to reach me.

PPPS. In a better world the NBA would move out the three point line so far that only Curry could hit them.