Pay/productivity gap graphs are nonsense

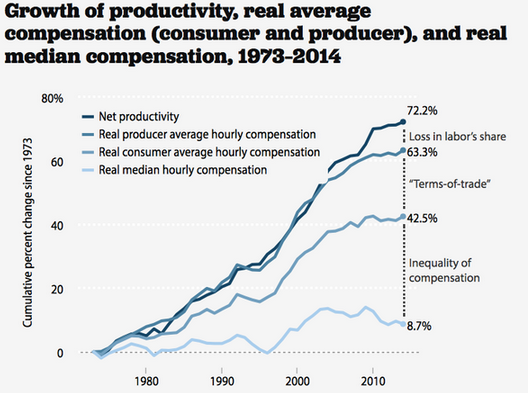

Matt Rognlie left three excellent comments after my recent pay/productivity post, which confirmed some of my suspicions, but also cleared up a few points I was slightly confused about. In doing so, he made me even more skeptical of the graph that supposedly shows a huge gap between growth in productivity and growth in pay. Basically the graph is bogus, and has no useful information on productivity and pay, which have risen in tandem since 1965.

Matt points out that a small part of the supposed gap reflects the fact that the diagram starts at 1973, a very good year for labor. As I pointed out (and Matt confirmed), the labor share of income has been stable since 1965, with a few ups and downs. And 1973 was an up year. One can debate which year is an appropriate starting point, but either way the labor share gap is no big deal.

It’s the terms of trade gap where Matt cleared up a misconception on my part. Although I didn’t mention this in the post (fortunately), I had assumed the gap reflected the fact that consumer goods prices rose faster than investment good prices. Rognlie shows that’s not the issue:

The other major component of the EPI graph is the “terms of trade” wedge, which is meant to be the gap between the price index for workers’ net output and the price index for their consumption. It’s important to emphasize that this is almost all spurious. This is clear enough from a quick sanity check – if you directly compare the behavior of the price indices for net domestic product (NDP) and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) since 1973, you’ll see that they have moved roughly in tandem: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=1OoA

[Some seriously lengthy and obscure price index discussion ensues…]

The EPI graph appears to show otherwise only because it opts to use the CPI-U-RS, rather than the PCE price index, to deflate workers’ compensation – and the CPI-U-RS has risen by 15% more than the PCE index since 1973. On its face, this seems pretty odd: for one thing, the NDP price index (like PCE) is chained while the CPI-U-RS isn’t. If you deflate net production by the former and compensation by the latter, the result is a “productivity-pay” gap that’s partly due to formula bias!

Matt provides much more detail, and is entirely convincing on this point. And I just want to make sure readers are not getting lost in the weeds here. This is not one of those “he said, she said” where reasonable people can disagree on whether the PCE or CPI is a better price index. This is a pay/productivity gap being invented by using the slowly moving price index (NDP, which is similar to the PCE) to make worker productivity look better, and the faster moving price index (CPI) to make real wages look lower. That’s not kosher. You need to use the same type of index for both lines on the graph.

So now we have demolished one part of the pay gap, and shown the other goes away if you start the clock in 1965 (still a good year for American workers, according to the left) and not 1973. What’s left is the biggest category, wage inequality. But of course it’s bizarre to put this on a pay productivity graph, as it has nothing to do with productivity and pay. It’s all about inequality of pay among workers. I’ll conclude with another Rognlie comment that points to the subtle sleight of hand involved in putting this on a pay/productivity graph; it makes readers think that low-skilled workers are not being compensated for their productivity, without actually providing any evidence that their productivity rose as fast as high-skilled workers. Here’s Matt:

So… as the lengthy digressions above demonstrate, neither the “loss in labor’s share” nor the “terms-of-trade” wedges in the widely circulated EPI graph are all that meaningful. The one remaining component that is unambiguously meaningful and important is the “inequality of compensation” gap, i.e. within-labor inequality.

Now, it’s not clear that this really belongs in a chart of the “productivity-pay” gap: the implicit assumption here is that there has been no change in mean vs. median labor productivity underlying the change in mean vs. median compensation. Needless to say, that’s a rather sketchy hypothesis – most economists would regard it as unlikely, and I don’t see much evidence for it.

It’s probably best to interpret the chart, therefore, as a clever way to rebrand plain old labor inequality: the idea that pay has failed to keep up with productivity sounds like more of a scandal than does “inequality” in the abstract. The scandal looks even bigger when you add the (dubious) terms-of-trade wedge on top.

Like Scott, I’m not moved much by this kind of rebranding, but I am a utilitarian who cares about distribution and individual welfare, so I am greatly concerned about the rise in within-labor inequality. That’s why I want to keep focused on that issue – and, with any luck, stop the endless tide of confusing productivity-pay charts.

Let’s end on a positive note. Krugman, Rognlie and I all believe that wage inequality is the real issue. Let’s stop with all this pay/productivity nonsense and focus on the real issue. Here’s a great proposal to reduce pay inequality, without raising unemployment.