China’s retail boom

In my view many pundits are excessively pessimistic about the Chinese economy, focusing too much on the weakness in heavy industry and exports. Offsetting that weakness is booming growth in retail sales, as Chinese incomes rise very rapidly. BTW, if China really is doing so poorly, then precisely WHY are Chinese incomes growing so rapidly? There are possible answers — fast rising unemployment or fast rising inflation — but I see no evidence of either. Here’s a recent report from Forbes:

Beijing’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that retail sales in China jumped 10.8% in August compared to the same month last year. That was substantially better than every consensus estimate. Analysts had predicted sales would come in at 10.5%, the same increase as July’s.

Most observers are bullish about consumption as the next driver of the Chinese economy. The dominant narrative tells us China is in a transition from investment-led growth to growth propelled by consumer spending. The oft-cited Andy Rothman, now at Matthews Asia, calls the country “the world’s best consumption story.”

The evidence supporting that proposition looks compelling. Apple, from the first indications of a few hours ago, immediately sold out its iPhone 6S and iPhone 6S Plus in China. Express parcel deliveries were up 47% in July compared to the same month in 2014. Box office revenues? For the first eight months of this year, theyskyrocketed 48.5% from the corresponding period last year.

Consumption contributed 50.2% of growth of gross domestic product in 2014. In the first half of this year, it accounted for 60.0% of GDP.

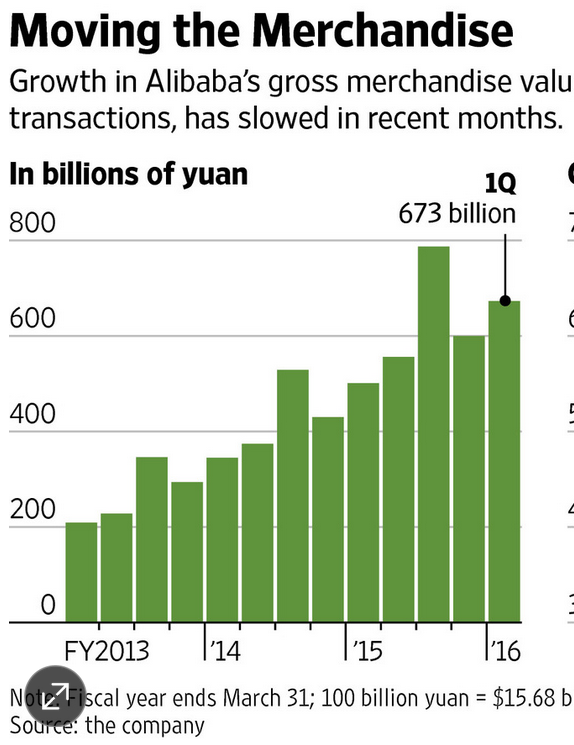

In recent years it has become trendy in China to buy goods online. Alibaba is by far the largest online retailer, so I thought I’d take a look at its numbers:

That graph is a bit misleading for two reasons. First, the latest figures are actually 2015:2, not 2016:1 (their fiscal year ends in March.) And second, growth is expected to slow modestly in Q3 due to the stock market plunge. But clearly the trend is very strong, and other online retailers show the same pattern:

That graph is a bit misleading for two reasons. First, the latest figures are actually 2015:2, not 2016:1 (their fiscal year ends in March.) And second, growth is expected to slow modestly in Q3 due to the stock market plunge. But clearly the trend is very strong, and other online retailers show the same pattern:

Three Chinese Internet companies””Alibaba, Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Baidu Inc.””are now among the world’s largest in market capitalization. The industry’s rise has come even as China’s economic growth has slowed from its double-digit pace of a decade ago.

Some other competitors are expressing caution, though many are signaling still-strong growth. Executives at Alibaba rival JD.com Inc. said last month that they expect third-quarter revenue growth of between 49% and 54%””compared with a year-earlier 61%””reflecting a “conservative outlook in light of the recent Chinese stock-market correction and the slowing macroeconomic conditions.”

Of course just as in America, some of this growth is coming at the expense of brick and mortar firms, and there are indications that sales are flat for many ordinary retailers. But don’t underestimate the importance of online; Alibaba alone now sells more than $100 billion dollars per quarter. If we assume the entire online sector is around $150 billion per quarter, then growth in that sector (year-over-year) is probably on the order of $50 billion per quarter, or $200 billion per year. Thus online growth alone can explain about half of the growth in China’s $4 trillion retail sector.

This relatively sunny view of Chinese retailing is one argument in favor of the Fed raising rates in September, although on balance I still think that would be a mistake. (Of course if China were actually sliding into recession, a rate increase now would be a mistake of epic proportions.) I strongly agree with Ray Dalio’s recent take:

Ray Dalio, the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, said the firm believes the next big move by the Federal Reserve will be to loosen U.S. monetary policy, not tighten it.

In a client note sent out on Monday, Dalio said the Fed is paying too much attention to the short-term ups and downs of the business cycle rather than the longer-term ramifications of central banks driving interest rates to zero, which now leaves them no room to act if worldwide deflation takes hold.

“The ability of central banks to ease is limited, at a time when the risks are more on the downside than the upside and most people have a dangerous long bias,” said Dalio, who helps manage $162 billion at Bridgewater. “Said differently, the risks of the world being at or near the end of its long-term debt cycle are significant.”

. . .

Dalio said the Fed has overemphasized the importance of the cyclical short-term business cycle in its desire to raise rates, but has been less attentive to the longer-term trend toward deflation.

He said the Fed will react “to what happens,” suggesting it should undertake more quantitative easing, or QE, but he isn’t positive of that, given Fed officials’ desire to raise rates.

Dalio warns of global disinflation, slow global economic growth, and the lingering risk aversion that is behind the proclivity to hold cash despite its significant negative real returns.

“Our risk is that they could be so committed to their highly advertised tightening path that it will be difficult for them to change to a significantly easier path if that should be required,” Dalio said.

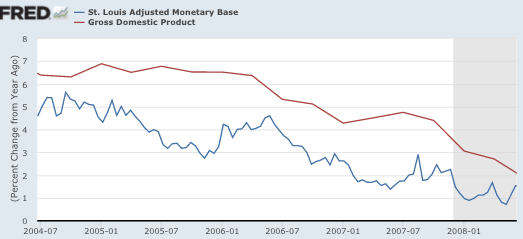

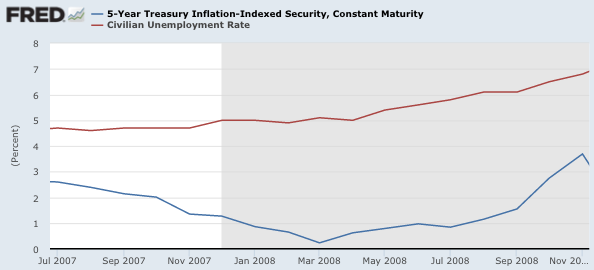

That final comment is especially important. This was precisely the mistake the Fed made in mid-2008, when many at the Fed assumed their next move would be higher. It was really hard for them to re-orient their thinking to the need for a rate cut, and hence they did not cut rates during the May through September period, when interest rate cuts were desperately needed. This effective tightening made the recession (which had already begun) much worse.

This time the probable consequences would be more benign, a slowdown in growth and undershooting the inflation target, not recession. But it would leave the Fed with fewer options when the next recession occurs.

HT: Ben