I recently listened to a very good interview of Tyler Cowen by Erik Torenberg. For me, it was 80 minutes of bliss. I tend to agree with the vast majority of his views (even one’s where I had no opinion until I heard his reasoning), with one notable exception—China. Tyler seemed very pessimistic about China’s short-term prospects, and seemed to think they were headed into recession.

I’m not sure the last time China had a recession; the last time they experienced sub-5% economic growth was 1989-90, and growth was still about 4% in each of those two years. I guess you could call that a growth recession. But I’m fairly confident that Tyler expects something considerably worse.

My general view is that most types of recession are almost unforecastable, and that the least bad prediction is always “more of the same.” (Here I’m thinking of ordinary demand shocks or financial crisis; a recession caused by something like the Syrian civil war can be predicted once the war begins.) Thus people who in 2007 didn’t predict a recession for 2008 were making sensible predictions, and those who did predict it were making foolish predictions, and just got lucky. So I’m going to predict no recession for China, this year or next.

Some might argue that there are good reasons to predict a recession, and that it’s not just a wild guess:

1. The Chinese stock market has collapsed.

2. The Chinese yuan has been devalued.

3. The Chinese macro data is ugly.

I say no, those three statements are all inaccurate. The Chinese stock market is about 20% below its recent peak, but still far higher than a year or two ago. There is nothing in stock prices to indicate a recession. You might respond that Chinese government intervention has made Chinese stock prices meaningless. Fine. Then let me rephrase that; there is nothing in Chinese stock prices to indicate a recession, because they are meaningless.

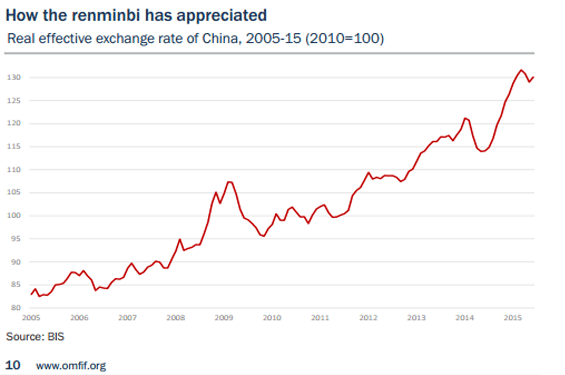

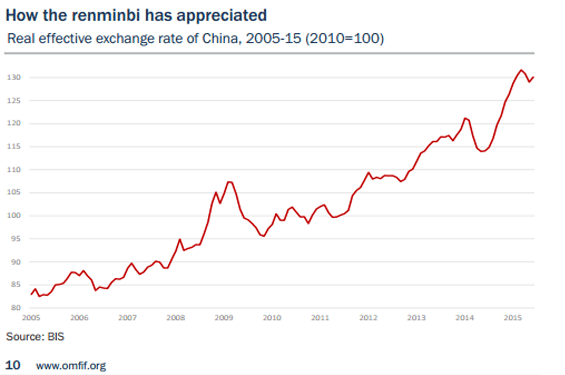

It’s also not accurate to say the Chinese yuan has recently been devalued. The value of the yuan against a basket of currencies has been trending higher for many years. Nothing significant has changed in that regard in recent weeks. The yuan is still higher than a year or two ago, still very strong against almost all currencies around the world. (Indeed too strong, and if a recession does occur it will be due to tight money.)

And the macro data does not indicate a recession. The Chinese economy has been growing at about 7% per year, and while I expect it to slow a little bit next year, I doubt the slowdown will be dramatic.

People often forget that with all its problems China still has enormous momentum. Let me just give you one example. China is building infrastructure at a very rapid pace, all over the country. The construction of infrastructure is itself a part of GDP. But the whole point of building infrastructure is that it provides services. Last year Beijing’s subways provided 3.41 billion rides, more than any other system in the world. But their subway system is still very inadequate, and is often extremely crowded. Many more lines are being built, and they’ll be busy too. Now think about the flow of services from the subway. In terms of Beijing prices it’s pretty low, as they price tickets at around 50 cents a ride. But at New York prices it would be closer to $10 billion/year. I can recall when Beijing’s entire GDP was about $10 billion. (Yes there’s been inflation, but still . . . )

That flow of subway services is much bigger than the year before and next year it will be much bigger still. And the same is true of 100 other examples I could cite. Despite what you read about “ghost cities”, there is still a enormous flow of people from rural shacks to modern urban apartments, yielding a massive and increasing flow of housing services—also part of China’s growing GDP.

China is still less that half as rich as Greece is at the bottom of Greece’s depression. Yes, China has lots of inefficiencies, such as state-owned enterprises, but they also have a labor market that’s dramatically more flexible than any labor market in Southern Europe, and which provides reasonably full employment and fast rising wage rates. Here’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard:

It is worth remembering that the authorities are no longer targeting headline growth. Their lode star these days is employment, a far more relevant gauge for the survival of the Communist regime.

On this score, there is no great drama. The economy generated 7.2m extra jobs in the first half half of 2015, well ahead of the 10m annual target.

Few dispute that China is in trouble. Credit has been stretched to the limit and beyond. The jump in debt from 120pc to 260pc of GDP in seven years is unprecedented in any major economy in modern times.

For sheer intensity of credit excess, it is twice the level of Japan’s Nikkei bubble in the late 1980s, and I doubt that it will end any better.

At least Japan was already rich when it let rip. China faces much the same demographic crisis before it crosses the development threshold.

It is in any case wrestling with an impossible contradiction: aspiring to hi-tech growth on the economic cutting edge, yet under top-down Communist party control and spreading repression.

That way lies the middle income trap, the curse of all authoritarian regimes that fail to reform in time.

Yet this is a story for the next fifteen years. The Communist Party has not yet run out of stimulus and is clearly deploying the state banking system to engineer yet another mini-cycle right now.

One day China will pull the lever and nothing will happen. We are not there yet.

I’m a bit more optimistic, as I think the reform process will continue. They’ll avoid the middle-income trap. But they haven’t yet even reached the trap—a lot more growth is ahead. If you want to know when that day of reckoning will finally arrive in China, don’t come here looking for answers. I will miss the collapse, blinded by the EMH, just as I missed every other dramatic economic shock in my entire lifetime. My predictions are boring, and always the same:

More of the same ahead

My predictions are usually right, but they get no respect, and don’t deserve any.

PS. I just talked to a Beijing resident who told me that people who cook and clean now make about $4/hour. That sounds low to Americans. But that figure’s been doubling every 5 or 10 years for many decades; 25 cents, 50 cents, $1, $2, and now $4. One more doubling and it would exceed the US minimum wage. Yes, I’d say within about 15 years something’s got to give in China. I don’t know when it will be, or whether there’ll be a soft landing, but I can’t see this blistering growth going on much longer.