Suppose that there are 6 ways the government could have prevented the 2008 financial crisis. One might be abolishing moral hazard (FDIC, TBTF, the GSEs, etc.) Another might have been to ban subprime mortgages made with taxpayer-insured funds. Another might have been higher capital requirements. Another might have been to require bankers to post personal bonds in case their bank failed (or needed to be bailed out), like on the old days. Another might have been NGDPLT. Etc., etc. In that case one might argue that failure to do one of those things “caused” the crisis. Of course there are many ways of thinking about causation, but I find policy counterfactuals to be one of the most useful ways of describing causation.

Before considering whether money causes NGDP, I like to consider some related questions.

1. I would argue that between 1879 and 1968 monetary policy “caused” the price of gold. For most of the period the price was fixed by the monetary policymakers. But even in 1933-34, when the price rose sharply, I’d argue it was “caused” by monetary policy, in the sense that the Fed was targeting the price of gold. In contrast, the Fed was not targeting the price of gold in recent years, so the increase was not caused by the Fed in any useful sense of the term ’cause.’

2. So if the Fed targeted gold prices from 1879-1968, does that mean other variables like the price level and NGDP were endogenous, and hence not caused by the Fed? It’s debatable whether they were completely endogenous, but let’s say they were. I’d still argue that the sharp decline in the price level and NGDP during 1929-33 was caused by the Fed. And that’s because I’d argue that gold price targeting was not a wise policy, and that a desirable counterfactual policy would have been to stabilize either the price level of NGDP during 1929-33. The Fed’s failure to do so caused the Depression.

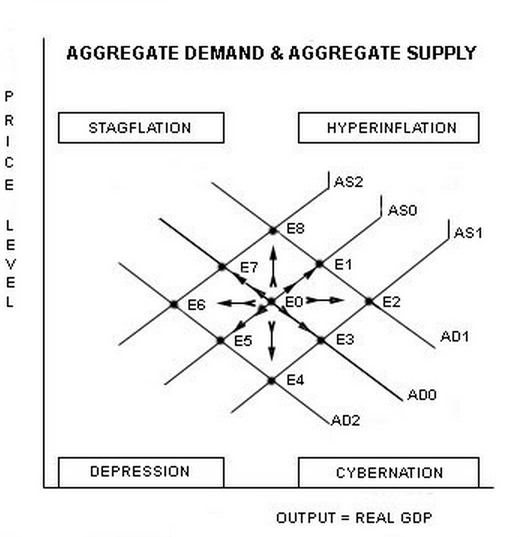

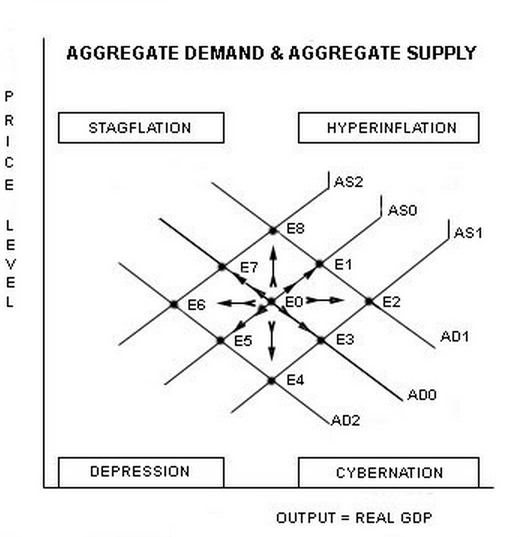

3. Now suppose the Fed is targeting inflation. In that case any change in RGDP growth will lead to an equal change in NGDP growth. Changes in NGDP will have nothing to do with monetary policy. Or at least it seems that way. But not necessarily. Suppose inflation is a bad target, because labor market instability (due to sticky nominal wages) and debt market instability (due to nominal debts) is much more closely related to NGDP fluctuations than to inflation fluctuations. In that case a central bank that is targeting prices could be said to have “caused” a deep recession by letting NGDP fall, even if it was hitting its inflation target perfectly, and RGDP was falling for other reasons. Of course it’s debatable as to whether its useful to consider the central bank to be to blame for the deeper recession, but it’s certainly not implausible, and indeed is the prediction of the standard AS/AD model used in econ textbooks. In the graph below when you are targeting P and there is a negative supply shock, then NGDP will fall. In that case you go to point E6, a deep recession. If you were targeting NGDP when this supply shock hit, you’d have a mild recession (E7) .

.

It’s certain fair game to blame the Fed for depressing AD in response to a negative supply shock, even if 100% of the fall in NGDP is “caused” by a fall in RGDP.

Nominal GDP growth is the sum of a real and a nominal variable; real GDP growth and inflation. And yet (paradoxically) NGDP growth is a 100% nominal variable, completely under the control of monetary policymakers. Whether it is useful to think in terms of NGDP fluctuations “causing” recessions depends on how you think the business cycle would be affected by a counterfactual policy of NGDPLT.

Similarly, changes in the nominal price of a gold (a 100% nominal variable) are the sum of a nominal and a real variable (inflation, and changes in the relative price of gold.) In 1933-34 it was useful to think of the rising price of gold at an indicator of easy money. More recently (in the early 2010s) it was not useful to think in terms of the rising price of gold as indicating an easy money policy. In 1933-34 the price of gold was used as a signaling device for the future path of monetary policy. That was not true in 2010-12. I’d like to use some of these ideas to analyze part of a Tyler Cowen post from a couple years back:

My worry is that some Market Monetarists speak of ngdp as if it is some block of stuff, handed down from on high (of course in the past our central banks have not been targeting ngdp). It’s as if ngdp determines the size of the room, and a carpenter is then asked to build a house within that room. If the room is too small, a large house cannot be built. Or, if you are not given enough clay, you cannot build a very large sculpture. Along these lines, if the growth path of ngdp is not robust enough, the economy cannot do well.

I get nervous at how ngdp lumps together real and nominal in one variable, and I get nervous at how the passive voice is applied to ngdp.

My framing is different. My framing is that the private sector can manufacture its own ngdp. It can do so by trade and it can do so by credit and of course velocity is endogenous to the available gains from trade. Most of the major central banks are, today, not obsessed with snuffing out recovery and increases in real output.

The value of money can be defined in terms gold, other currencies, all goods and services, and share of NGDP that can be bought with a dollar. These all involve an inverse relationship; 1/Pgold, or 1/price of foreign currency, or 1/price level, or 1/NGDP. Thus NGDP can be viewed as a single thing (one way of describing the value of money), or of course it can also be viewed as a composite (P and Y, or M and V). If someone is used to viewing policy in terms of money supply targeting, or price level targeting, then an NGDP discussion can seem odd—adding together two very different things. As I said, if you target P (or M) then NGDP will seem to fluctuate due to “non-monetary factors” like supply shocks (or V shocks.)

But that tells us nothing about whether it is useful to think in terms of NGDP being causal, i.e. whether NGDPLT is a useful policy counterfactual. So while Tyler’s argument is defensible, the average reader would probably assume that Tyler has spotted a logical error in the NGDP fanatics, which is actually not there. (In fairness, elsewhere he explicitly denies doing so.)

Go back to the opening analogy in this post. I favor eliminating moral hazard. But it wouldn’t be fair of me to accuse someone who favored higher capital requirements for banks as having ignored the real cause of banking crisis. At best I could argue my solution was more useful. Perhaps Tyler should have discussed which alternative monetary policy targets are the most useful. The commenter who sent me this post thought (probably wrongly) that Tyler was criticizing NGDPLT. I don’t see that. He was claiming it’s not the cure-all some of its proponents seem to think it is.

To say “ngdp is low,” or “ngdp is on a low growth path,” or “ngdp is below trend,” and so on “” be very careful! Those claims do not necessarily have causal force. Arguably they are simply repeating, in a new and somewhat different language, the point that the private sector has not seen fit to engage in more trade, credit creation, velocity acceleration, and so on. Formally speaking, the claims are not wrong, but I don’t find them useful as an explanation for why economic growth or recovery, at some point in time, is slow. It is one way of repeating or re-expressing the slowness of economic growth, albeit with some transforms applied to the vocabulary of variables.

This paragraph touches on both the “causality” and the “usefulness” perspectives I discussed earlier, but in what seems to me to be a somewhat unsatisfactory fashion. Start with the final two sentences. He’s saying that by 2012 enough time had gone by so that wages and prices should have adjusted. That’s an eminently plausible argument. The final sentence can be thought of as an alternative hypothesis. Say we are targeting P or M, and output is slowing for Great Stagnation reasons. In that case NGDP will also slow (or might slow in the M targeting case) and MMs like me might wrongly attribute the slowdown in RGDP to a slowdown in NGDP. And that’s certainly possible.

When Tyler wrote the post the most recent reported unemployment rate was 8.1%, for August 2012. Now it’s 5.9%. I believe the most useful explanation for that sharp fall is that NGDP has been rising faster than nominal wages in the US. Tyler says central banks were not trying to snuff out the recovery. But we do know that in 2011 the Fed was trying to speed up the recovery while the ECB was trying to reduce inflation by raising their target interest rate. And we know that NGDP in 2011-13 grew much more slowly in the eurozone than the US. And we know that unemployment rose sharply in the eurozone, while it fell sharply in the US. So while Tyler is right that movements in NGDP need not have any causal effect on RGDP, I believe that it just so happens that we live in a universe where it does have a causal effect, or at least that it is useful to talk in terms of causal effects from NGDP.

This matters when we consider sticky nominal wages. Sometimes it is suggested that the “inside workers” have frozen up or taken up so much ngdp with their sticky wage demands that the outsiders cannot find the ngdp to fuel their activities. It’s as if there is not enough ngdp to go around, just as there was not enough clay to make a sufficiently large sculpture.

Yes, workers and firms can behave in a way that overcomes any shortages of NGDP. Indeed Tyler and I agree that in the long run they WILL behave in a way that overcomes any shortage of NGDP. But these metaphors are expressed in a slightly misleading way. The average reader would have a great deal of trouble figuring out whether Tyler is expressing a new classical argument that nominal shocks don’t matter, and that real GDP is determined by real factors, or a NK/monetarist argument that nominal shocks matter in the short run but not the long run, and that September 2012 is now the long run, or the hybrid theory that nominal shocks might matter in the short run, but not if the short run NGDP changes are caused by real factors such as less aggregate supply. A close reading of his other posts shows he believes the nominal shocks matter in the short run, but many of the (skeptical) NGDP metaphors employed here are also applicable to the short run. Do they apply to a case where AS and AD are entangled?

So for instance, suppose a central bank is targeting inflation. Then suppose an adverse supply shock reduces RGDP by two percent in the short run, even in the best of circumstances (i.e. stable NGDP). But also suppose that NGDP falls with the supply shock (as Tyler correctly noted might happen.) My claim is that in that case RGDP would fall by more than 2%, perhaps 4%. What does Tyler believe? The metaphors he employs seem to suggest that he is skeptical of this claim, but elsewhere he argues that nominal shocks do matter in the short run, so falling NGDP should make the recession worse.

PS. Two years ago I did a post in response to this same Tyler Cowen post. I did this post without looking at my earlier post, and ended up with something very different. Maybe in two more years I’ll do a third.

PPS. I do agree with Tyler that framing effects are important. In microeconomics there is one dominant framing method, and hence you don’t see as many cases of microeconomists who are Nobel Prize winners call each other idiots as you do in macro, where different framing effects lead to almost a complete failure of communication.

PPPS. Election today? All I care about are the referenda. Both major parties have sharply declined in quality over the past 20 years. Both deserve to lose.