How many economists can answer this question?

Dustin asks an interesting question:

An elementary question on the topic of interest rates that I’ve been unable to resolve via google:

Regarding Fed actions, I understand that reduced interest rates are thought to be expansionary because the resulting decrease in cost of capital induces greater investment. But I also understand that reduced interest rates are thought to be contractionary because the resulting decrease in opportunity cost of holding money increases demand for money.

One? Neither? Both? Little of each? Depends?

It’s not at all clear that lower interest rates boost investment (never reason from a price change.) And even if they did boost investment it is not at all clear that they would boost GDP.

But two things are very clear:

1. Open market purchases reduce short term nominal rates.

2. Open market purchases boost NGDP.

However it’s surprisingly hard to explain why OMPs boost NGDP using the mechanism of interest rates. Dustin is right that lower interest rates increase the demand for money. They also reduce velocity. Higher money demand and lower velocity will, ceteris paribus, reduce NGDP. So why does everyone think that a cut in interest rates increases NGDP? Is it possible that Steve Williamson is right after all?

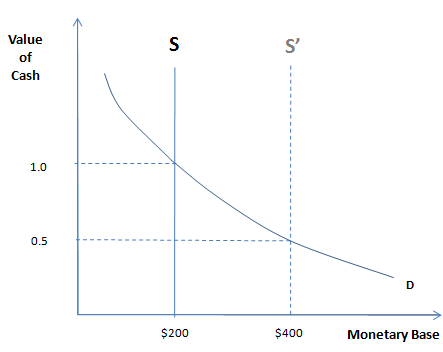

Here’s what people forget. The Fed doesn’t wave a magic wand and reduce interest rates. They do so via a boost in the monetary base. Now let’s think about the effect of a sudden and instantaneous 1% boost in the monetary base. Contrary to most macro models, there is an immediate impact on NGDP, although almost certainly less than 1%. The instantaneous impact on NGDP comes from the fact that the OMP immediately boosts commodity prices, and hence the gold and oil flowing out of the ground in America has a higher nominal value. But that’s nowhere near enough to instantly boost NGDP by 1%. Instead interest rates must fall by enough so that Americans are willing to hold extra non-interest bearing base money. The lower interest rates reduce velocity in the short run. So NGDP might rise by 0.2%, and V might fall by 0.8%, within seconds.

In the very long run money is neutral, V is unchanged, and NGDP rises by 1%.

The medium term is the most complicated. There may well be a period when velocity goes up, especially if inflation rises and real growth is strong.

So the correct answer is that the lower interest rates tend to reduce NGDP, but the thing that causes lower interest rates may increase NGDP by more than the reduction caused by lower V. At least if that “thing” is OMPs.

Yes, easy money often makes rates fall in the short run, but it’s the larger money supply that does the “heavy lifting” of boosting NGDP.

And here’s my claim, if a student asked Dustin’s question in a typical American econ class, the professor would struggle to answer the question. What do you think? Note that to answer the question you must address the specific concern raised by the student (lower rates causing rising demand for money in this case.) It’s not enough to wave off that concern and answer it using an unrelated model, say New Keynesianism.

Now suppose interest rates were cut via lower interest on reserves. How would the answer be different? Lower IOR would reduce the demand for money, which would boost NGDP. No increase in the monetary base would be necessary. No wonder that many anti-monetarists are so anxious to move to a world of IOR. They are embarrassed by some inconvenient facts about the impact of lower interest rates in a world of OMOs involving zero interest base money.

PS. Some have claimed that in the brave new world of IOR we won’t need OMPs to target NGDP. Perhaps with a zero growth rate target path that would work. But if you want 5% NGDP growth, then IOR would have to fall fast enough to lead to 5% velocity growth. Eventually you would blow right through the zero bound, and need negative IOR. Even on currency. Velocity would rise faster and faster. After being paid workers would run to the store to spend their money. Then they’d start using jetpacks. Eventually the speed of light might put an upper limit on V, and hence NGDP.

I’d rather stick to good old OMPs.