Will China own 1/2 of the planet?

I was reading a study by Garett Jones in the Asian Development Review and came across this interesting tidbit:

Modern optimizing macroeconomics begins with the Ramsey growth model, where time preference plays a large role. If national average IQ differs across countries, and if the IQ-time preference relationship discussed by Shamosh and Gray (2008) holds across countries, then the Ramsey model makes a strong prediction. That is, in a closed-economy world, high-IQ countries will save more and have larger ratios of capital to output. Jones and Podemska (2010) provide evidence that this theoretical prediction holds true in practice. They found that the correlation between national IQ and a nation’s capital-output ratio is 0.64.

Further, in an open-economy world, the Ramsey model predicts that high-IQ countries will ultimately own all of the world’s capital (Barro and Sala-i-Martin 2003). In the modern world, presumably somewhere between those two extremes, we might expect high-IQ countries to hold, at the least, a disproportionate share of the world’s globally traded low-risk assets. And that is indeed the case. Since the mid-1990s, when reliable data first became available, a nation’s average IQ has been positively correlated with the ratio of US Treasuries to that nation’s nominal GDP (Jones and Podemska 2010). In 2007, the correlation between national IQ and that nation’s Treasury-GDP ratio was 0.39, and the relationship remained statistically significant when controlling for log GDP per capita.

As long as East Asian countries (and Singapore) continue to have the world’s highest average IQs””not a foregone conclusion, to be sure””conventional growth theory predicts that these countries will hold a disproportionate share of the world’s globally traded low-risk debt. The predictions of theory hold in the data””indeed, the empirical relationships are actually stronger than conventional theory predicts, as demonstrated in Jones and Podemska (2010).

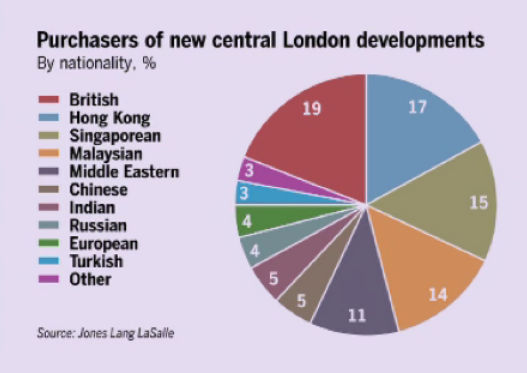

Then Matt Yglesias directed me to a fascinating Tim Fernholz post with this graph:

So let me get this straight. The ethnic Chinese are already buying up half of all the best real estate in London. And of that share, 45% comes from a tiny number of Chinese in Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia, and the other 5% from the 1.4 billion mainland Chinese who are ultra-thrifty but haven’t yet gotten rich like the 20 million Chinese in those three small economies. Care to estimate the share of planet Earth that will be owned by the Chinese in 2075, once the mainland becomes rich?

PS. After doing the post I came across this:

President Obama has become the first president in 22 years to issue a formal order blocking a foreign investment into the United States on national security grounds. The decision, which denies the acquisition of a small Oregon wind farm project by a Chinese-owned company, will unfortunately be seen as yet another signal – this time from the highest possible level “” that the United States does not really want Chinese investment. And for an economy still struggling to create jobs, that’s the wrong signal to send.

Yeah! That’ll stop the Chinese!