“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean””neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master — that’s all.”

Paul Krugman recently made the following claim:

The shared starting point here is that we are in a situation in which the Fed would clearly cut rates if it could; based on historical relationships between unemployment, inflation, and policy rates, the Fed funds rate “should” be something like -4 percent. But the Fed can’t do that.

I think that’s probably right, although I doubt the Fed would cut rates by 400 basis points, even if they were able to. But why not cut the fed funds target? The conventional answer is that it “wouldn’t do any good, as nominal rates can’t fall below zero” (or even below the IOR rate, if you want to be picky.) That’s true, but while there’s a lower bound on the actual fed funds rate, there’s no lower bound on the fed funds target.

Before you assume I’ve completely lost my mind, I strongly suggest readers take a look at this provocative Nick Rowe post:

The natural rate of interest is not a number; it’s a time-path. And the central bank doesn’t observe that time-path, so when it sets the actual rate it will almost always miss the natural rate time-path. And when the economy is off that time-path, that will cause the time-path to shift. Because expectations will change. And because reality will change too, as investment changes and capital stocks (understood in the broadest sense to include human capital and the stock of employment relations) change too. So, while useful as a theoretical concept, the natural rate of interest is perhaps not so useful as a practical guide to monetary policy as the Neo-Wicksellian approach requires.

Which is perhaps why all of us, central banks especially, should stop framing monetary policy in terms of interest rates. Setting interest rates is not what central banks really really do. It’s a social construction of what they do. When central banks talk about setting interest rates that is only a communications strategy, and not a very good communications strategy, especially at times like this.

[Update: Tom Hickey asks: “So monetary policy boils down to central bank communications leading to expectations?”

My response: That’s 99.9% of it, yes!

So cutting the fed funds target to negative 4% isn’t quite as good as cutting the actual fed funds rate to minus 4%, it’s only 99.9% as good. In other words, it’s like cutting the actual fed funds rate by 3.996%. I’ll take that!

By now many of you are looking for the flaw in my argument. You won’t find it. At least you won’t find a flaw in the logic. Instead you’ll plunge down a rabbit hole into the endlessly paradoxical world of monetary policy. A world where it’s not at all clear what the Fed “really does.” Does it control the money supply, control interest rates, or control NGDP expectations? Where it’s now believed that what really matters is the expected future path of policy, and current policy decisions work primarily by changing expectations of future policy.

Almost everyone now agrees that during normal times a temporary $10 billion dollar open market purchase will temporarily reduce short term interest rates. And almost everyone believes that if the OMP is expected to be reversed in one month, it will have almost no impact on the macroeconomy. And almost everyone agrees that if the OMP is permanent it will result in roughly 1% higher prices and NGDP in the long run. The implication of all this is that current monetary policy actions matter, if at all, by changing expectations of future monetary policy.

Assume that during normal times the Fed sees indications that NGDP will grow at slightly less than the desired rate of 4.5% over the next 12 months. They might respond with a cut in the fed funds target, which the markets take as a signal that the Fed intends to do what it takes to boost expected NGDP growth back up to 4.5%. Some conceive of that action as lowering the expected future path of rates relative to the natural rate, other see it as raising the expected future money supply. But the key is expectations—if you don’t change expected future policy, you aren’t going to significantly impact the macroeconomy.

The program called “QE2” consisted of the Fed exchanging an interest-bearing risk-free government liability called excess reserves for another interest-bearing risk-free government liability called Treasury securities. One can make a pretty good argument that this program “didn’t do anything” in a narrow technical sense. But nonetheless markets responded in the following fashion:

1. Equity prices rose on the news.

2. Inflation expectations rose on the news.

3. The dollar depreciated on the news.

That’s quite a bit of activity for a program that “didn’t do anything.” Of course it did do one thing—it communicated something about the Fed’s determination to do whatever it takes (over a long period of time) to prevent the economy from slipping into deflation.

Nick Rowe has argued that once rates hit zero the Fed loses its ability to communicate, at least in its preferred language. I’ve accepted that argument, and to some extent I still do. But not completely. I now think that the Fed should have developed a back-up plan for how to operate at the zero bound, how to communicate policy intentions. At one time I thought they had (partly based on my reading of Bernanke’s academic work.) Now I can see that they don’t have any coherent strategy, and are just making it up as they go along.

I strongly believe that interest rates are the wrong policy instrument. But most people disagree with me. Even when the Fed does QE, they justify it as an action that will reduce long term rates. They seem completely unable to communicate to the public in any non-Keynesian language. OK, then why not keep talking Keynesian?

Here’s my suggestion: If the Fed is committed to communicating in terms of the fed funds rate, why not continue to have the Fed set a “shadow fed funds target.” The proposal would work as follows. The FOMC would continue to meet every six weeks and vote on the fed funds target that would be most effective in communicating their macro policy goals. For instance, this might be the number that results from the Taylor Rule formula. No consideration would be given to whether this was a positive or negative number. Then the Fed would announce the target, and instruct the New York trading desk to get as close as possible (which would be zero, or perhaps the IOR rate.)

In my view this policy would be a disguised form of semi-level targeting. This will require some explanation, as most people are used to thinking in terms of growth rate targeting. But first a digression on policy since 2008.

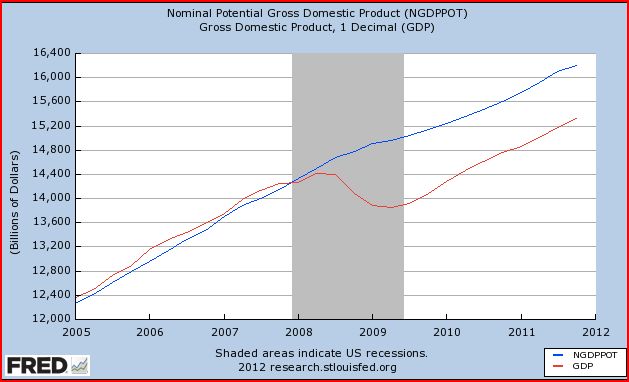

In the opening quotation Paul Krugman overlooks one weakness in his argument. The fed funds target was above zero during the entire collapse of NGDP from June to December 2008. This collapse is best seen using monthly NGDP estimates from Macroeconomics Advisers:

This might be viewed as a policy error, perhaps partly due to lags, partly due to backward-looking policy, and partly due to the mistaken belief that the banking crisis was the “real problem” and that saving banking was the key to preserving NGDP growth. But whatever the cause, the Fed had three choices. Try to go all the way back up to the pre-2008 trend line (level targeting.) Try to go part way back (semi-level targeting.) Or start a new trend line from the 2009 trough (growth rate targeting.) They actually chose the latter option, although it’s not clear if this was intentional, as the Fed is highly secretive about its NGDP policy goals.)

Once rates hit zero, the most effective Fed actions were steps that would communicate the policy goal. In practice, they’ve behaved as if they were doing growth rate targeting. (Let bygones-be-bygones and go for 4.5% NGDP growth from the 2009 low.) But it’s certainly possible that they would have preferred semi-level targeting, i.e. going at least part way back to the original trend line. I strongly suspect Bernanke would have preferred faster NGDP growth, but it’s hard to read the overall FOMC because it includes members that seem to use a non-mainstream macroeconomic framework, and hence talking about the “FOMC view” requires rather heroic assumptions.

Under my plan the 2010 meeting that led to QE2 might have gone as follows: The FOMC meets and sees that NGDP growth is slower than they’d like. They vote to cut the shadow fed funds target by 1/2%, from negative 2.75% to negative 3.25%. This sends a signal to the markets that the Fed will engage in future policy actions to raise NGDP slightly faster than the markets previously expected. Interestingly, that’s exactly how monetary policy works in normal times, or at least that’s 99.9% of how it works. The other 0.1% is that a small change in the fed funds rate over just the next 6 weeks actually affects a few investment decisions.

For those readers from the “concrete steppes” who have trouble visualizing how a purely symbolic fed funds target can impact the macroeconomy, you might try the standard Keynesian explanation. The Fed is known to move slowly and methodically, it’s highly inertial. If the fed funds target falls from minus 2.75% to minus 3.25%, then it pushes the date where rates are expected to rise above zero out further into the future.

(BTW, I don’t see that as being the mechanism, rather I see it “working” by increasing the future expected level of cash in circulation, but I’m in the minority.)

OK commenters, now’s your chance to tell me what an idiot I am.

PS. I’d pay a lot of money to see Ben Bernanke start quoting Humpty Dumpty next time he testifies in front of Congress.

Update: I see from the comments that people are missing the point–probably because I tried to get too cute. Here it is:

1. During normal times the Fed communicates its NGDP intentions (or weighted average of inflation plus output gap, if you prefer) with fed funds target signals. During January 2001, September 2007, and December 2007, the equity markets immediately swung plus or minus 4% to 8% over Fed decisions about whether to cut rates by 1/4% or by 1/2%. To put it bluntly, the markets don’t give a s*** what the fed funds rate is over the next 6 weeks, they care about these anouncements because the Fed is signalling its future intentions for NGDP. Yes, it would be easier if they would explicitly tell us where they want to go, but they won’t.

2. The Fed wrongly thinks it’s communicating by changing the fed funds rate, but the markets are responding to the fed funds target, and what that tells us about the future path of monetary policy.

3. Because the Fed wrongly thinks the actual fed funds rate over the next six weeks is what is important, they wrongly believe they have gone “mute” once rates hit zero, they don’t think they are able to communicate with the markets.

4. But they haven’t gone mute, the actual fed funds rate over the next 6 weeks is an epiphenomenon of monetary policy, it’s the fed funds target that signals the actual (long run) policy. They can use that target to signal future policy intentions regardless of where the actual fed funds rate is, as long as future interest rates are expected to rise above zero. (If they aren’t expected to then the government should just monetize the national debt.)

5. If they thought about things correctly, in a Nick Rovian way, they’d realize they had never really lost their voice, they just thought they had.

6. If they insist on talking interest rate talk, then don’t stop talking once rates hit zero!