Here’s the conventional wisdom from Renee Haltom at the Richmond Fed:

Changing the Rules

The Fed’s policymaking committee discussed NGDP targeting at its November 2011 meeting and provided a hint that major changes are not on the table. “We are not contemplating at this time any radical change in framework,” Chairman Bernanke said after the meeting. “We are going to stay within the dual mandate approach that we’ve been using until this point.”

Central bankers don’t take changes to the conduct of policy lightly. All central banks face the temptation to boost growth for temporary gain at the expense of longer-run price stability. To convince the public that monetary policy won’t give in to that temptation “” to therefore maintain credibility and keep inflation anchored “” many central banks stick to consistent “rules,” either explicit or implicit, to effectively tie their own hands.

Radical change? Bernanke has recently emphasized that the Fed takes its dual mandate seriously. He indicated that they put equal weight on both sides of the mandate. I recall he responded to a conservative senator with something to the effect that if Congress wasn’t happy with their policy they should give them a different mandate. And of course the Fed influences employment by affecting RGDP growth. I wouldn’t say the Fed puts equal weight on inflation and RGDP growth, but Bernanke’s comments about the dual mandate suggest their policy is pretty close to NGDP targeting.

And yet Haltom is right that a switch to NGDP targeting is generally viewed as a major change in Fed policy. That got me wondering if it would be possible to do a policy that looked very much like current policy, and yet was almost identical to NGDP targeting. Given Bernanke’s insistence that both sides of the mandate (inflation and employment) are treated equally by the Fed, it ought not be too difficult. I’d like to hear your suggestions, but here’s one idea. The Fed announces that it will fulfill its dual mandate as follows.

1. It will aim for 2% core PCE inflation every single year.

2. It will aim for RGDP growth equal to the average RGDP growth rate of the previous 20 years.

This policy will tend to produce roughly 2% headline inflation over any long period of time. Importantly, it will aim for 2% core inflation even in the short run. The RGDP target is aimed at the Fed’s employment target. High employment is more likely to occur in an environment where RGDP growth and inflation are relatively stable. Indeed my preference would be for the Fed to “target the forecast”, that is, set policy such that it is expected to hit this target.

Now let me anticipate objections:

1. No, this isn’t trying to hit two targets at once, it is a single target; NGDP growth equal to the 20 year moving average rate of RGDP growth plus 2% inflation. That’s a single number, a single target.

2. It answers one popular objection to NGDP targeting, the fear that the price level would no longer be anchored. This still anchors inflation at 2% over the long run. The math is kind of complicated, but the average inflation rate would approach 2% as the time period approached infinity. Thus if trend growth fell from 3% to 2%, as may be occurring right now, there would be a transition period when inflation would temporarily exceed the 2% goal. But then it would asymptotically fall back to 2%. And the reverse would occur when the trend rate of RGDP growth rose. When trend growth is stable then inflation should be stable at 2%.

In contrast, under NGDP targeting a fall in trend RGDP growth from 3% to 2% would leave inflation permanently higher.

The more I think about this idea the more I like it. The 2% inflation target is “locked in” to this system, not left to chance. It’s an explicit 2% inflation target. The system gives equal weight to inflation and employment fluctuations. The Fed is trying to keep inflation at 2%, and trying to stabilize employment. This gives it a definite target, no more of the ambiguity that drives both liberals and conservatives nuts when they are trying to evaluate Fed policy. We can finally hold them accountable. We can say; “We’ve instructed them to do X, now let’s see how close they came to doing X.” As it is, it’s hard to hold them accountable, because their interpretation of the mandate is so vague.

Consider Haltom’s second paragraph quoted above. I think she expresses the conventional wisdom, but I’m not sure that’s true. Ever since Lehman failed inflation has averaged just over 1%. This is quite odd, given the Fed’s dual mandate. If you think about it, even 2% inflation would have violated the dual mandate, as it would have implicitly given zero weight to jobs. If inflation had been 2% over the past three years, the Fed should have been trying to raise inflation above 2% to reduce unemployment. Does anyone serious believe they would have, given that even at slightly over 1% inflation it was really hard to get them to explicitly try to raise inflation?

And how about the BOJ, or the ECB under Trichet? Do they seem like central banks just chomping at the bit to print money, but help back by inflation targets? Japan’s had mild deflation for nearly 2 decades. And Trichet bragged that he drove inflation to a level far below that of the Bundesbank in the midst of the greatest debt crisis in European history.

As I look at world history, it looks to me like the major central banks were constantly trying to boost growth until about the early 1980s, and since then have constantly been obsessed with reducing inflation.

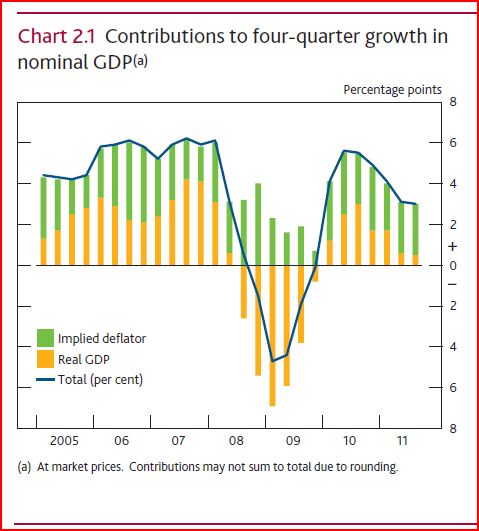

I don’t know why these multi-decade long mood swings affect our central banks, but it needs to stop. NGDP targeting would be ideal, producing a perfectly calm ocean surface over which the ship of free market capitalism could sail. But my “20 year average of RGDP growth plus 2% inflation” idea is almost as good. It would produce very long and graceful swells in the economy’s surface, barely detectable to most people. Even a tsunami is hardly noticeable in the middle of the ocean. A 20 year moving RGDP average plus 2% inflation isn’t much different from a fixed NGDP target, but looks much more like a dual mandate featuring 2% inflation targeting, and it also anchors inflation in the long run. What’s not to like Mr. Bernanke?

PS. I’ve ignored the level targeting vs. growth rate targeting issue, as I think we first need to get a consensus on what type of target. This proposal could be amended to go either way, although I obviously prefer level targeting.