Do the QE opponents have ANY good arguments?

I hope this is my last attack on conservative opposition to QE2, as I am getting sick of the topic. I’ll try to summarize all their arguments here, to see if any are even slightly defensible:

1. Inflation only seems low because the Fed ignores food and energy.

The core rate is only 0.6%, but even the overall CPI is only running 1.2%. So that argument is flat out wrong. Yet it doesn’t stop some people from making it.

2. History shows that when central banks print lots of money, high inflation results.

Actually no. History shows that when central banks print lots of money at the zero rate bound, one generally doesn’t get much inflation. Japan has been printing lots of money for years, and has also run big budget deficits—thus they’ve been monetizing the debt. And their price level is lower than in 1994.

3. Japan is different. When the Fed has printed lots of money we’ve had high inflation.

Actually no. Again, when at the zero rate bound, printing money is not necessarily inflationary. The Fed printed lots of money in the 1930s, indeed the monetary base nearly tripled. Yet the price level fell during the 1930s.

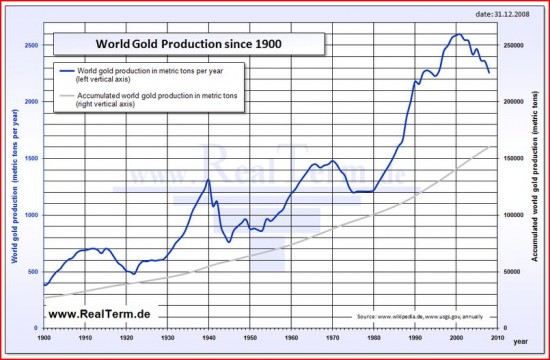

4. The gold market shows that high inflation is just around the corner.

Actually no, for reasons discussed in this earlier post. Every direct indicator we have of inflation expectations shows very low inflation in the years ahead. CPI futures markets, 5-year TIPS spreads, the consensus economic forecast, they all point to low inflation.

5. OK, in the past printing money didn’t produce high inflation at the zero rate bound, and we don’t have high inflation now, and both forecasters and markets tell us not to expect high inflation in the future. But I just can’t believe we can print that much money without eventually suffering from high inflation. Monetarist theory tells us . . .

Monetarist theory has nothing to do with the current policy environment. Monetarist theory is all about the impact of printing non-interest bearing money–aka “high-powered money.” The reason it’s called high-powered is because it lacks interest, and thus is a sort of “hot potato,” an asset that everyone tries to get rid of, and the in process drives up prices. Milton Friedman and Karl Brunner would be rolling over in their graves if they knew people were claiming monetarist theory meant than the issuance of reserves paying interest at rates higher than earned on T-bills was some sort of “high-powered money.”

6. If the policy does raise NGDP, interest rates will also rise, causing the Fed to suffer capital losses on its large bond portfolio.

Conservatives presumably believe in efficient markets, and thus the expected loss is approximately zero. The term structure of interest rates has already priced in the expected increase in rates that will occur as the economy recovers. Yes, there is some risk, but far less than people think. The Fed is mostly buying medium terms bonds, for which the price risk is rather low. And if the recovery is much stronger than expected, the gains to the Treasury would far exceed the losses to the Fed. This is NOT an argument for leaving millions of workers unemployed. Especially given that the Fed took far greater risks to save the big banks.

7. Yes, they are paying interest in reserves, and that prevents inflation right now, but when the economy recovers there will be tremendous pressure on the Fed to avoid raising the interest rate on reserves, and they will spill out into the economy.

Even distinguished economists such as Becker and Posner are making this argument, but I find it the most perplexing and feeblest argument of all.

Right now the Fed is under tremendous pressure not to do more monetary stimulus, despite 9.8% unemployment and below target inflation. There is little pressure on the Fed to do more. Yet somehow we are to believe that when the economy recovers somewhat and inflation is much higher, and unemployment is lower than today, there will be tremendous pressure on the Fed to not raise rates? And all this despite the fact that the Fed is almost universally blamed for holding rates too low for too long, and inflating the housing bubble? That makes no sense.

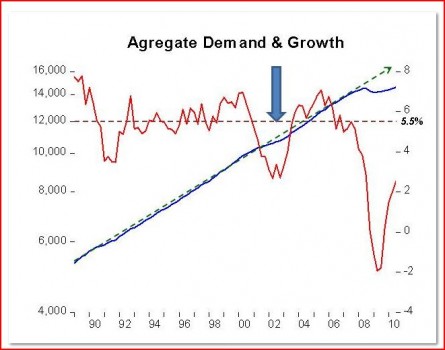

Even worse, we need easier money to reduce that part of unemployment that is not structural; almost certainly a substantial share of the 8 million jobs lost in the recent recession was cyclical. NGDP is not now growing fast enough to rapidly reduce unemployment. I don’t expect the 11% NGDP growth we saw in the first 6 quarters of the (low inflation) Volcker recovery of 1983-84, but surely we can at least raise NGDP growth a bit higher than the current path? How can we in good conscience tell the Fed not to do the right thing, and ease the enormous suffering caused by unemployment, solely because we fear they might do the wrong thing in the future? Especially given that there is little political pressure on them to inflate now, when you’d think the political benefit of easy money would be greatest? Obama didn’t even nominate three people for empty Fed seats for 15 months, which shows how little the liberal establishment cares about monetary policy. And we are to believe that in the near future when the need for monetary stimulus is far less, Obama will suddenly morph into a latter day William Jennings Bryan and start pressuring the Fed?

So there you are. The conservatives do not have a single good argument against QE2. Every argument is based on bad logic, bad economics, a lack of understanding of history, or a lack of understanding of our political system. There must be some reason why the conservative establishment hardly raised a peep when the Fed would cut rates when inflation was running 3% or 4% when Reagan was president, or when Bush was president, and yet are now up in arms over monetary stimulus when we have 1% inflation and 17 million people out of work. There must be some reason. But for the life of me, I can’t figure out what it is.

OK, I’ll get off this topic, and wait for conservatives to explain to me what’s going on.

And when we figure that out, then we can work on the even more bizarre opposition from certain voices on the left. But perhaps I should leave it to Krugman to figure out what’s going on in the mind of that other outspoken, prickly, left-wing pundit and Nobel laureate. Joe Stiglitz.