Hayek would have told the ECB to print more money

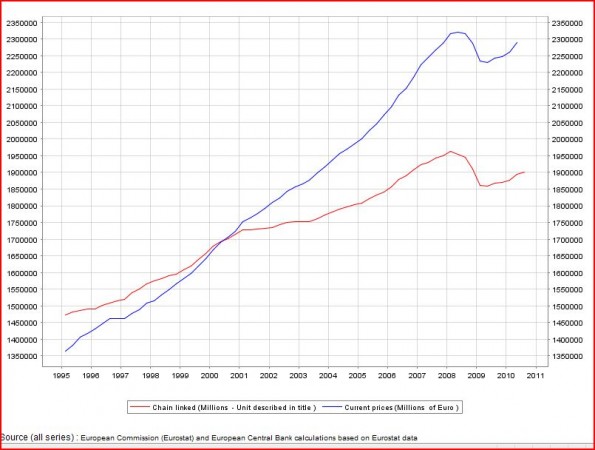

Luis Arroyo sent me the following graph:

I get frustrated when I read people arguing the Eurozone problem is that the ECB can’t come up with a one-size-fits-all policy stance. As if monetary policy is too tight for just a few small stragglers on the edge of Europe, comprising just a few percent of the Eurozone GDP. Actually money is even tighter in Europe than in the US. It’s too tight for every single Eurozone member. Nominal GDP is well below the levels of early 2008. Obviously in that situation many people, businesses and governments will have difficulty repaying their nominal debts. Look at the path of nominal income before the crisis (blue line); that’s the income trajectory that people and governments were expecting when they contracted their nominal debts.

Obviously several small countries made extremely foolish decisions. Greece faked its national accounts and Ireland agreed to bail out bank creditors. So they’d be facing some problems under the best of circumstances. But without the big drop in NGDP the Eurozone debt crisis would be far smaller, indeed would be relatively easily contained with a few bailouts.

How ironic it’d be if the ECB destroys the euro it was set up to protect, by obsessively trying to raise its value. They should have consulted King Midas.

Or perhaps Hayek, who warned what would happen if nominal incomes were allowed to decline.

HT: Thanks to Luis, and to Niklas Blanchard who finally taught me how to right-size graphs.

Tags: F.A. Hayek

27. November 2010 at 14:34

Graph isn’t right sized here. Oh well – a good post nonetheless.

And I hope and trust that the entire MoneyIllusion community had a wonderful Thanksgiving.

Money isn’t everything after all.

And my very best to everyone.

And if anyone wants to know how to invest money – read this:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/27/your-money/27money.html?_r=1&ref=business

27. November 2010 at 16:34

Some related question(s), Sumner. The Krugman is jabbering on about Ireland as a failed experiment in Austerity. He, as usual, wants more so-called “stimulus”. He does, however, acknowledge that Ireland went through a genuine economic miracle before the bubble times took over (via easy money I contend).

So, here’s the questions.

#1. Didn’t Ireland’s government institute some serious spending cuts as part of the reforms that sparked this “miracle” and, if so, doesn’t that make Krugman’s model a bit, ehem, problematic.

#2. Has Ireland actually done any real “austerity” yet to warrant claims that it has caused their recession? I don’t trust Krugman on the facts or the sequence or the casual claims.

Sorry if this is diverging from NGDP… but at least it’s part of the general topic.

27. November 2010 at 17:29

Great article JimP! And Happy Thanksgiving to you and everyone else at MI too!

John Papola:

I think that Krugman, as a good counter-cyclical Keynesian, has always pretty much said that budged cutting is most appropriate in periods of economic growth.

He has also said that it is appropriate even in periods of contraction, *if* it is possible to counterbalance its effects with either currency devaluation or monetary stimulus or both. (see http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/18/fiscal-fantasies-2/)

He also thinks that whatever the case for austerity in the weakest countries, central banks and national governments in the strongest countries should be turning the stimulus up to 11 at this point.

If the ECB and the Fed were doing their job properly, then Ireland could still have austerity while benefiting both from increased demand in the Euro Zone and the U.S., as well as from relative devaluation against other major currencies.

What is wrong with those claims?

27. November 2010 at 18:06

I think the graph dramatically makes the case why things are so bad in precisely those periphery countries that should not shoulder any blame(Ireland and the Baltic States). The reduction in liquidity hit those areas of the EU the hardest that were growing the most rapidly.

You can austeritize until the cows come home. Until NGDP in those countries is where it was before the massive reduction in money supply they will be in perpetual crisis.

27. November 2010 at 18:19

JimP, The right margin is covered up, but I don’t care about that. Thanks for the article about investing. From jerk to nice guy in one life.

John, I don’t see how Ireland can even do stimulus, as the ECB determines AD in Ireland. I don’t know enough about Ireland, however, to really comment on their situation. I notice the minimum wage is being “slashed” to $10.35/hour, that doesn’t seem like austerity to me. If they are serious about stimulus, they really need to leave the euro. But it’s possible that the costs of leaving might be bigger than the benefits. I can’t understand why they guaranteed those bank debts. Was it simply corruption?

Shane, Yes, Krugman is completely correct that the Fed and ECB should be doing much more. Ditto for the BOJ.

Mark, I agree. And the Baltic states show that even with their own currency Ireland wouldn’t have any easy choices. But their debt crisis was self-inflicted, not caused by the ECB. They actually don’t have that big a deficit, other than the massive bank bailout.

27. November 2010 at 18:27

Scott wrote:

“And the Baltic states show that even with their own currency Ireland wouldn’t have any easy choices. But their debt crisis was self-inflicted, not caused by the ECB.”

Sure, they pegged, and they could have chosen not to. But what would the Austerians said if they had depreciated?

And don’t underestimate the pain (especially in Latvia).

27. November 2010 at 18:33

Yglesias has a post up about the PIIGS adopting dual currencies: issuing new national forms of legal tender that are pegged against the Euro for intranational purchases, but that float against other currencies, including the Euro, on international markets (http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/11/de-euroizing-spain/). So pace Yglesisas, those within the borders of Spain get to spend Euros and “Espanolas” (why not just call it the Peseta again?) in an interchangeable fashion, but anyone with Euros could exchange them for Espanolas (URGH!) at market rate.

I’ve heard similar things proposed for depressed regions of the U.S. (meet the “Michigander,” the local Michigan currency). Any thoughts out there on this idea? I guess it might be appropriate to ask a lawyer’s opinion as well as an economist’s opinion.

27. November 2010 at 19:51

Well the ECB can come up with a one-size-fits-all policy stance. However, they can’t come up with one that is appropriate for the hugely diverse economies of the EZ. Taking into account the language barriers preventing labour mobility, different levels of labour market flexibility, no standard banking regulation and widely different inflation it is difficult to see how they could ever have an appropriate one-size-fits-all policy.

In Ireland real interest rates averaged minus 1 per cent 1998-2007. With the removal of currency risk the imbalances were not going to lead to interest rate rises. Absent EMU the overborrowing would have led to interest rate rises. Better regulation of their banks could obviously have helped prevent the worst excesses. However, during this period policy was too loose for Ireland but appropriate for Germany. The main problem now for Ireland and the rest of the periphery is they have lost wage competitiveness.

The ECB policy stance is always going to be determined by the euro core and Germany in particular. The main raison d’être for the euro was a convergence of borrowing costs and that is now effectively defunct. The ECB has really lost control of the situation and absolutely no one is saying ‘ don’t fight the ECB ‘. The only way I can see the euro project survive in anything like its current form is if they adopt a common debt euro-bond. The EFSF instrument could be the beginning of pooled debt. However, it will require the periphery to surrender sovereignty over their budgets to a central authority. Otherwise why would the core want to pool borrowing costs when they can already refinance cheaply. I suppose you could call it a one-size-fits-all fiscal stance.

27. November 2010 at 20:25

Scott, could you point me to the source of Hayek’s nominal income targeting recommendations?

27. November 2010 at 20:43

John Papola,

Check out this by David Beckworth:

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2010/02/hayek-and-stabilization-of-nominal.html

27. November 2010 at 21:20

It is an odd time of ultra-low inflation, even deflation, and yet some economic commentators calling for austerity and tight money. Some seem to have conflated a tight fiscal policy with a tight monetary policy.

Keep banging the drum that money is oxygen for a growing economy.

Remember, the anti-QE2 crowd are the “Nipponists.”

27. November 2010 at 23:18

This looks like my country circa 2001. Things won’t end well if policy isn’t changed.

@Shane,

“Yglesias has a post up about the PIIGS adopting dual currencies:”

Yglesias should read on the Argentine crisis and the experiments with complementary currencies and barter [1]

1- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patac%C3%B3n_(bond)

28. November 2010 at 01:12

Thanks, Scott, I´ve translated and published it in

http://cuadernodearenacom.blogspot.com/2010/11/de-money-illusion-de-scott-sumner-quien.html

Mi blog Ilusión Monetaria (inspired on your´s as you remember). When I saw the graph I can´t believe it.

But don´t worry, that is a question which don´t worry in the ECB.

ECB manage an unknow model that always say: chit chit, too much inflation Mr Trichet, you must rise interest rate. BTW, Madame Merkel is watching you.

28. November 2010 at 04:40

Scott – I have to disagree.

For one, you need to disaggregate the data – Germany and France are in a very healthy position and most German and French people will tell you the same. RGDP growth in Germany is expected to touch 3.7% in 2010 and unemployment is lower than it was at the height of the pre-crisis boom.

It’s all and well to say that the ECB should do more but what exactly more? It is already the only buyer of last resort for PIIGS debt via its repoing of bank purchases of sovereign debt. Indeed, the Irish crisis was triggered by the ECB essentially figuring out that it had way more Irish debt on its balance sheet was prudent. Same was true of Greece – local Greek banks bought Greek govt debt and repoed it with the ECB. Moreover, the ECB has the most lax repo collateral standards of any big central bank. Almost any single-A rated asset on a European bank’s balance sheet can be repoed. Given how easy it is to manufacture a single-A rated asset, anything that cannot be repoed with them is probably toxic junk.

The ECB has traditionally always been calibrated to the German and French business cycles which was the problem in the pre-crisis when Ireland and Spain in particular got easy money when they needed tight money, thus triggering off a real estate bubble. Right now, they’re calibrated as far to the needs of the periphery as they possibly could be. Anything more than can be done needs to be fiscal for which there is no public appetite in Germany.

28. November 2010 at 06:32

Scott:

I only half agree with you here.

Yes, monetary policy is too tight for the Eurozone as a whole.

But, the central bank is supposed to act as lender of last resort, to prevent self-fulfilling expectations leading to runs, not just on banks, but on government debt. And the ECB is conspicuously failing at that latter job. And the failure is in the periphery, not in Germany and France.

28. November 2010 at 07:12

Nick:

A lender of last resort is only supposed to lend to solvent institutions. Greece, Iceland and Ireland do not qualify on that score. It’s questionable whether or not Spain and Portugal do.

In any case, the Euro is doomed. There are too many cultural and language barriers to labor mobility within the EU to make a single currency a good idea. Look at California, which is doing horribly right now, vs. Texas, which is not nearly as bad. If California had it’s own currency, a depreciation would be called for. It doesn’t, but at least some of its unemployed can move to Texas. It’s not so easy for an unemployed Spaniard to move to Germany.

(This touches on another reason the recession is so bad. If you’re underwater on your mortgage, it’s harder to move to an area where jobs are more plentiful. But this is just another example of how too much debt throws sand in the gears of the economy.)

The sad part is that these problems were well known before the Euro was set up, but they went ahead with it anyway.

28. November 2010 at 07:15

Mark, I think you misunderstood me on Latvia–I agree with you.

Both choices had problems, it’s very possible that devaluation would have been better.

Shane, If they are going that route, why not go 100%.

I don’t know enough to have a good sense of how bad things are in Spain. In my view the market expectation of default (bond premiums) is the best guess we have.

Richard, I agree that one-size fits all is “a” problem for the eurozone, I just don’t think it is “the” problem they are facing now.

I agree that Ireland needed “better” regulation, as you said. In my view “better” would have meant less corruption and insider dealing. I.e. less total regulation and more honest regulation.

You said;

“The ECB policy stance is always going to be determined by the euro core and Germany in particular.”

I recall talking to a German economist a while back and he said many Germans felt money was too tight at the time. Spain had something like 4% inflation, and Germany was close to zero (with high unemployment.) How things have changed. So I’m not sure it always favors Germany.

John, Lawrence White has a recent article in the Journal of Money Credit and Banking on Hayek’s views. You can google it.

Thanks Mark.

Thanks Benjamin.

Lucas, Do you live in Argentina?

Thanks Luis.

Ashwin, The French economy is certainly not in good shape, the unemployment rate is higher than ours, and has been rising. Germany has a bit lower unemployment, but that is misleading. Their output has fallen just as far as our output–their recession is just as deep. They put workers on short hours–so it looks like unemployment hasn’t risen, but it has. Even Germany, the most successful big eurozone country, has lower output that two years ago (unless I am mistaken.)

ECB policy should reflect the aggregate nominal output of the eurozone, not one or two countries. Would you want Fed policy to cater to Texas and California? That would make no sense.

Nick, Then we completely agree. I certainly wasn’t defending their policy on the debt issue, I was just trying to show that they don’t even have the correct monetary policy stance.

28. November 2010 at 07:25

@ Ashwin

France have to refinance in excess of 20 per cent of their GDP next year. Large scale refinancing is also taking place next year in Italy and Belgium. With this in mind tensions could easily spread to core sovereign markets. I don’t consider France in a ‘healthy’ position.

28. November 2010 at 09:36

The problem is to distinguish between The positive and the normative aspect. Normative would say that ECB should be the central bank of the Euro Zone. the fact is that is the central bank of Germany (and perhaps Danmark and Holland).

In the past Germany has needed -and obtained- a loose monetary policy, but today the party is over: Germany is booming, so no more “inflationary policy”.

So, not only ECB is a conservative central bank: it is the bank of a few countries. France is not capable of change this situation.

I suppose Scott is talking about what a central bank in a country should do. But eurozone is not a country, is a mess.

I ask myself how Spain (or Irland, or Greece, or Portugal) with a unemployment rate of 20%, will return its debt if NGDP is lower that 2 years ago and with no expectation of growth. If the interest rate will rise, the debt will not be paid.

Sure there are a lot of wrong things that should be reformed. But (as Bernanke would say), an increase of unemployment from 9% to 20% is not a problem of labor market only

28. November 2010 at 09:40

John Papola,

You wrote:

“So, here’s the questions.

#1. Didn’t Ireland’s government institute some serious spending cuts as part of the reforms that sparked this “miracle” and, if so, doesn’t that make Krugman’s model a bit, ehem, problematic.

#2. Has Ireland actually done any real “austerity” yet to warrant claims that it has caused their recession? I don’t trust Krugman on the facts or the sequence or the casual claims.”

I just noticed your questions this morning. I think the answers to your questions are the following:

#1 I wouldn’t characterize the Irish reforms that sparked the “Celtic Tiger” as involving overall spending cuts so much as involving spending restraint. As the economy took off the government sector continued to grow but at a slower rate than GDP. However, spending was reprioritized in such a way that led to more public investment in infrastructure and human capital at the expense of other forms of government expenditures.

#2 Within the OECD, Ireland was one of only three countries (along with Iceland and Hungary) out of 30 which actually engaged in fiscal tightening as of March 2009. This was of course the opposite of what other OECD members were doing. Ireland enacted tax increases over 2008-2010 roughly equal to 4% of annual GDP and spending cuts equal to 1% of of annual GDP. The Baltic States also engaged in fiscal austerity early on. But I would argue that monetary policy is a far more important reason for their current plight.

Ashwin,

You wrote:

“For one, you need to disaggregate the data – Germany and France are in a very healthy position and most German and French people will tell you the same. RGDP growth in Germany is expected to touch 3.7% in 2010 and unemployment is lower than it was at the height of the pre-crisis boom.”

Germany did have good RGDP growth in 2010Q2 (mostly due to a surge in exports), and that will be reflected in the annual data. But given that their RGDP plunged 6.8% from peak to trough this recession (compared to 4.1% in the US) they had a lot of ground to make up. And unemployment is only so low in those countries because of worksharing.

Much of the positive talk that you hear from France and Germany these days is missguided chauvinism. An honest appraisal of the data clearly suggests that even the core countries in Europe are suffering from an equal if not larger reduction in trend growth in NGDP and RGDP than the US.

Scott,

You wrote:

“Mark, I think you misunderstood me on Latvia-I agree with you.”

I realized that. That was just a clumsy effort on my part at clarifying my views.

28. November 2010 at 09:53

Scott

You wrote:

“Even Germany, the most successful big eurozone country, has lower output that two years ago (unless I am mistaken.)”

I just noticed your response to Ashwin. Consequently I wasted some breath repeating some of your points.

However, you are not mistaken. As of 2010Q3 RGDP in France and Germany was still 1.8% and 1.7% below previous peak respectively in 2008Q1. By contrast last quarter the US was 0.6% below its previous peak which was 2008Q2. Even if one allows for a greater population growth rate in the US I don’t think that the core of Europe is doing much better.

28. November 2010 at 10:00

@Scott,

“Lucas, Do you live in Argentina?”

Yes, I’m an Argentine.

The 2001-2002 crisis has left a deep mark on our generation. I was finishing high school in those years. I have lively memories of the December 2001 riots [1]

1- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/December_2001_riots_in_Argentina

28. November 2010 at 10:15

Scott

This is Kling almost “pure atheist”:

“Overall, macroeconomics is problematic for those with diffuse priors. One can observe a Scott Sumner who is totally convinced that monetary expansion now is warranted. And one can observe a John Taylor who is equally adamant that monetary expansion now is not warranted. And, of course, one can observe Prad Krulong adamantly arguing that we are in a liquidity trap that requires more fiscal stimulus. Not to mention those of us who have doubts about the whole paradigm of aggregate supply and demand.

What should a policy maker do? In my view, a fiscal expansion is high risk, given the long-term debt outlook. A monetary expansion is lower risk. If we get more inflation, well, we were going to get it sooner or later, given the fiscal outlook. The worst case is that we get it sooner rather than later.

But, of course, my priors lean to the view that neither fiscal nor monetary expansion will do much good”.

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2010/11/macroeconomics_4.html

28. November 2010 at 16:12

This story about a pre-election administration economic team meeting raised hairs on the back of my neck. Evidently somebody important among the President’s economic advisers thinks that the unemployment problem in the US is largely structural.

“More generally, I can’t think of any Democratic-leaning economists who think the problem is largely structural.

Yet someone who has Obama’s ear must think otherwise.”

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/lacking-all-conviction-2/

Actually, given the fact they left three FOMC seats empty for two years while the Fed Presidents browbeat Bernanke I’m not surprised. But still, I wonder, who? (And how many?)

And when you have Republicans slamming QE2 in a WSJ petition the last thing you need is someone in the administration essentially agreeing.

28. November 2010 at 22:07

What’s so nice about this graph is that you can clearly see in the mid-2003, BOTH comfortable negative trend lines are bastardized, and we’re now right where we should be with both.

Meaning, if we continued living with the kind of growth we saw after the Internet crash, we’d be slightly below where we are now.

So you shouldn’t be pretending we should have this much cake. You should be hoping we’re done with the diet. We’re not going to get any of that back.

I see NO logical reason to pretend a trend line from 2006-2008 is reality. Nothing you’ve said so far justifies the assumption.

29. November 2010 at 04:21

Scott

Germany takes it’s medicine as a country, the sort of thing you admire in Sweden. It doesn’t cheat by printing money. Unemployment is now at an 18 year low. The economy is booming, to them, or growing unspectacularly to nominal GDP junkies. They don’t fear deflation but accept it as the price of stability, and believe things will come right in the end. The German consumers are famously conservative and generally believes in living with their means. US consumers believe in living the dream, or bust.

29. November 2010 at 06:25

Luis, Interesting that you include Denmark in that list, but not Austria. Denmark is not in the eurozone, although their currency is pegged to the euro.

Is Germany really booming? Their RGDP is back to where it was several years ago. That seems to be a pretty weak performance.

I agree that Spain has labor market problems, but they also had 20% unemployment a few years back w/o any debt problems. The debt problems mostly come from the big drop in eurozone NGDP.

Mark, Thanks for all that info, I agree with your appraisal.

Lucas, Yes, but I read that many Argentineans blamed neoliberal policies, whereas the actual problem was tight money.

Marcus, Yes, needless to say I don’t agree with Kling on monetary stimulus.

Mark, I was a bit less appalled by that info about Obama. At least it shows he’s not in a cocoon, at least he is considering alternative views. Obviously I don’t agree with that alternative view, and I doubt many of his advisers do either, but you’d like an open debate on policy.

Morgan, The trend line goes back for decades, plus you are confusing NGDP and RGDP. There is no natural limit to NGDP

James, What medicine? And why is printing money “cheating?” And why compare Germany to Sweden, which devalued? And RGDP is lower than 2 years ago, which is hardly “booming.” If unemployment is at a record low then the German workers must be spectacularly unproductive, as output is lower than several years ago, despite a growing workforce.

29. November 2010 at 06:33

I am not sure there is as much disagreement between you and those who say the problem is a one-size-fits-all (OSFA) as you imply. I don’t think most OSFA people would disagree that overall monetary policy is too tight. I also doubt most OSFA people would disagree that targeting Germany and France alone is crazy, though the contention is that that is more or less what the ECB does due to political quirks in EU.

One can certainly argue that monetary policy is somewhat too tight for Germany, but it is catastrophically tight in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland. Would Germany stand for a monetary policy geared towards the aggregate NGDP trend, if that implied via the logic of weighted averages that Germany’s NGDP growth needed to be above trend?

Perhaps the bigger disagreement is over the importance of the Euro area being a non-optimal currency area in building up the imbalances? It seems to me to be a pretty strong contributor, though surely not the only one, especially if you look at the divergance in unit labor costs. I assume you disagree?

Lastly, on Ireland, it’s a good question as to why the government guaranteed the bank debt, one that doesn’t get asked enough. I think corruption played a part, though I am sure the banks and politicians grossly underestimated the amount of debt they were ultimately guaranteeing.

29. November 2010 at 08:57

[…] QE2 & THE EUROPEAN CRISIS — WHAT WOULD HAYEK DO? By Greg Ransom, on November 29th, 2010 David Beckworth gives some reason to believe that Hayek would have supported QE2. And Scott Summers make the case for believing Hayek would have supported monetary easing in Europe. […]

29. November 2010 at 12:16

when you have a china that keeps the yuan artificially the cheapest so they can sell their wares,

you better lower your own currency lower than the yuan,

because you have got your own wares to sell too.

the way to do it is to print like hell.

think of one yuan exchanging for two euros.

29. November 2010 at 14:09

Brad DeLong – Friedman would have supported QE2. Case closed.

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2010/11/milton-friedman-suppors-ben-bernanke-on-qe.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+BradDelongsSemi-dailyJournal+(Brad+DeLong's+Semi-Daily+Journal)

29. November 2010 at 14:16

And from the same Friedman speech – on the Euro.

http://everydayecon.wordpress.com/2010/11/29/friedman-on-ireland-and-the-euro/

29. November 2010 at 15:55

Scott,

I was actually able to find fed fund futures reaction to the December 2007 25 (rather than 50) basis point cut. The only problem : for some reason they only provide data on the January meeting outcome and not March (still, I’ll argue this data supports your point).

Here is a link to the data. You can download an excel file at the bottom for more detail.

http://www.clevelandfed.org/Research/data/Fedfunds/archives.cfm?dyear=2007&dmonth=12&dday=13

Here are the probabilities for before and after the December meeting…

FF Rate – Probability on December 10 – Probability on December 11

3.50 – 18.7% – 6.5%

3.75 – 7.0% – 24.3%

4.00 – 40.8% – 40.1%

4.25 – 30.1% – 28.6%

4.50 – 3.4% – 0.5%

At first glance, it seems like after a disappointing 25 basis point cut markets simply swapped the chance of the FF rate being 3.5% in January to 3.75%. But the average expected FF rate actually stood still (fell very slightly actually). That should be surprising given that the Fed cut by less than expected. I think the markets thought that even though the Fed screwed up, they wouldn’t be willing to cut 100 basis points in one meeting. Beyond that though, they actually saw less of a chance of rates being 4.00-4.5% in January even though the rate cut was less than expected.

(In the end the rate ended up being 3% after the January meeting FYI!)

It’s disappointing they don’t have data for a later meetings. Those would likely better show expectations of further cuts than the January one. Still, I think this data proves your point relatively well. The expected January cut in rates basically increased by 10 basis points as a result of a disappointing cut. That’s an unusual reaction to a tighter policy unless you though the fed screwed up and would later be forced to cut more.

29. November 2010 at 16:10

Scott I’m still not seeing it:

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_b6CLevEGCD0/S_rsp_mYa8I/AAAAAAAAByw/hIp5NOLFqVY/s1600/ngdp_forecast.jpg

Where do we see decades of historical NGDP with inflation factored out?

Something tells me you’re still going to be pointing at trend from an obviously unsustainable period, when we should have been pissing on booms.

29. November 2010 at 16:54

Morgan, take a look here.

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2009/11/global-nominal-spending-history.html

29. November 2010 at 18:59

The author is absolutely correct, that Hayek would have wanted the Eurozone to keep the supply/demand ratio of its currency stable.

A central bank pursuing a deflationary policy…including one where money supply grows, but not enough to keep up with demand…is doing even more harm to the economy than an inflationary policy (which is, to be sure, harmful itself).

Unfortunately, that’s what you can expect from any central bank, or other monopolistic authority.

This is why Hayek advocated a free market in money, NOT either a fiat gold standard or fiat paper money.

The US is in its depression, in significant part, because from 2004-2008 its domestic money supply was growing too slowly…at a 60 year low.

Europe’s apparent effort to prove how kewl and strong its currency is through the metric of a relatively useless exchange rate is doing nothing but harm to the European Union.

The only really important factor of the exchange rate is how it impacts imports/exports. In that regard, the Euro is harming Europe, as industrialists there have been screaming about for years.

29. November 2010 at 19:49

Scott

Linking to the Friedman speech JimP mentions:

http://www.bankofcanada.ca/en/res/wp/2000/keynote.pdf

The Q&A section is “creepy” (on QE and Euro problems). And makes me wonder about the “intelectual honesty” of Krugman that never misses a chance to say “Friedman was wrong” while “praying” at the end of his NYT column today for the “spirit” of Friedman to “shine” over the Fed!

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/29/opinion/29krugman.html?_r=1&hp

29. November 2010 at 21:32

Thanks Edwin (and David), but I’m still not seeing it, what I see is Scott’s assertion that when we’re doing 5% NGDP things are pretty good, higher than that and they start to suck.

What I want to do though is take a recent time when we were barely growing, but growing, and removing the last 6 years from our data, figure out where we should be now – MINUS the housing crisis.

I could care less about what has happened since 2008, things were supposed to go down, the wrong people had the hard assets, because 2004 onward was also bullshit.

So I took 2001 – the GDP is: 10.578TRILLION

at .05% in 2009 it is: 15.629TRILLION

With inflation calculated that $15.6T is worth: $12.872T in 2001 dollars.

So it looks to me like accounting for inflation we gained close to 25% GDP since 2001, which is about Scott’s after inflation target right?

30. November 2010 at 04:45

A Cato working paper:

Has the Fed been a Failure? George Selgin, William D. Lastrapes and Lawrence H. White

Abstract:

“As the one-hundredth anniversary of the 1913 Federal Reserve Act approaches, we assess whether the nation’s experiment with the Federal Reserve has been a success or a failure. Drawing on a wide range of recent empirical research, we find the following: (1) The Fed’s full history (1914 to present) has been characterized by more rather than fewer symptoms of monetary and macroeconomic instability than the decades leading to the Fed’s establishment. (2) While the Fed’s performance has undoubtedly improved since World War II, even its postwar performance has not clearly surpassed that of its undoubtedly flawed predecessor, the National Banking system, before World War I. (3) Some proposed alternative arrangements might plausibly do better than the Fed as presently constituted. We conclude that the need for a systematic exploration of alternatives to the

established monetary system is as pressing today as it was a century ago.”

http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=12550

30. November 2010 at 06:09

OGT, I mostly agree with your comments. On the optimal currency zone question I’d say “it depends”. The more effective the ECB is at stabilizing total NGDP growth, the larger is the optimal currency zone. The more inept the ECB the greater the advantages to weaker members having their own monetary policy.

Good point about the Irish underestimating the risks of guaranteeing the debt.

I’ve been warning for 15 years that Fannie and Freddie were ticking time bombs, but even I grossly underestimated the risks. I thought a disaster this big was highly unlikely. It’s funny how society insures against small risks, and then treats the entire banking system like a giant casino, where the taxpayers are on the hook for much more than they ever dreamed they would be (also in Iceland.)

Thanks JimP, I had a post on the same topic, with almost the same name in mid-September (also titled “case closed.”

Cameron, Thanks for getting that data, it is very helpful. I’ll do a post at some point.

Morgan, Why was NGDP growth in 2001-08 unsustainable? It was no faster than during previous decades.

Kaz Vorpal, I would also like to reduce the Fed’s discretion, and have markets determine monetary policy.

Marcus, Yes, Krugman owes more to Friedman than he realizes.

Nick Rowe has a recent post on that.

Morgan#2, I don’t have an after-inflation target.

Bonnie, Thanks, I did a post on that paper a couple weeks back entitled “There’s no going back.”

30. November 2010 at 07:48

As in 08 the world is short dollars. In 08 the short was covered with unlimited swap lines. Will the Fed create the dollars this time?

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2010/11/30/420776/its-a-much-bigger-dollar-squeeze-this-time/

30. November 2010 at 09:03

Even if economists could agree on what the ECB should do, politically it is very complicated. The EU is not (yet) the US of Europe, but people are trying, see for instance this interesting plea : http://www.pdf.lacaixa.comunicacions.com/ee/eng/ee37_eng.pdf

30. November 2010 at 09:09

Scott should give Alan Reynolds a lesson on inflation expectations:

http://www.cato-at-liberty.org/david-wessels-curious-defense-of-the-feds-ambiguous-mandate/

30. November 2010 at 11:12

One last thing on Fed Funds Futures: I found another good site with charts covering the entire lifespan of FF futures contracts 2007 to present.

http://futures.tradingcharts.com/historical/ZQ/2008/C/linewchart.html

Interestingly markets were expecting an increase of the FF rate to 2.75% by year end in June 2008 and it wasn’t until early/mid September 2008 that markets actually thought rate cuts were more likely than rate increases.

30. November 2010 at 12:07

Krugman-

“The good news about America is that we aren’t in that kind of trap: we still have our own currency, with all the flexibility that implies. By the way, so does Britain, whose deficits and debt are comparable to Spain’s, but which investors don’t see as a default risk.”

They don’t see a risk because (a) Britain has just had an election and now has a stable coalition government with a substantial parliamentary majority that will almost certainly be in power until 2015 and (b) this government has set out a steady, vigorous programme of cuts that are going to be coupled with both monetary and supply-side (a shift from corporation tax to consumption tax and lower state spending) stimuli. All in a country with a flexible exchange policy (the BoE can intervene on the currency markets if necessary, but doesn’t have to do so) and a flexible labour market.

If Britain had similar political instability to that of Ireland or Spain (say a minority Labour-Liberal Democrat government) coupled with a major government figure who was somewhere to the left of Stiglitz on fiscal policy (Ed Balls, now in the Shadow government) and a plan to defer fiscal retrenchment until at least 2011, the UK would be on the same route as Spain, Italy, Portugal and Belgium. And we wouldn’t have the same case for the Germans to prop us up, which would further spook the markets, so we’d probably be off to the IMF. Again. The UK would then end up having to cut faster and deeper than otherwise, while also struggling with high interest rates and the markets looking sceptically at the pound.

I understand Krugman’s ideological opposition to cutting public spending, but to seriously suggest that the UK could get away without cutting government spending has now become untenable in my view. I think it was a matter of judgement back in June, but with the advantage of hindsight the strategy set out back then has probably got Great Britain away from being the second “G” in “PIIGGS”.

The main problem, instead, is that many of our main trading partners are now in such a mess. It’s easy to forget how much the UK exports to small European countries like the Republic of Ireland.

30. November 2010 at 12:23

As for the EU (in its post-1992 incarnation) and the euro: both were essentially “fair-weather” political entities, like Third Way social democracy or compassionate conservativism. In a time of bad weather, their prospects for success are bleak.

One of the hardest jobs in the civil service is forcing politicians, almost none of whom are natural decision makers, to choose X over Y or vice versa. Politicians’ training, such as it exists, consisting in thinking about what they want to do, rather than what they want to sacrifice. After all, in a democracy, it’s thinking and speaking in that way which wins elections.

Hence politicians loved the EU and the euro, which promised both the rigorous stability of Teutonic monetary policy with the power of controlling fiscal policy; free trade, but with limits on politically sensitive areas like agriculture; a chance for Belgian politicians to be respected on the world stage, but no suspiciously Napoleonic common army etc.

All of which worked very well in the era of Third Way social democracy and compassionate conservativism, but floundered in the face of economic crises. For example, it’s not clear that the possibility of a peripheral country leaving the euro was ever seriously considered, even though this had been a problem in the predecessors of the euro. Until the Lisbon Treaty, there wasn’t even a mechanism whereby a country could leave the EU.

Equally, when faced with having to cut spending and raise taxes, politicians who have spent most of their careers finding the “middle ground” (i.e. spending without raising taxes via steady growth) are now having to rediscover their priorities. Like public spending? Then you can’t have low taxes. Like low taxes? Then you have to be prepared to cut spending.

The long term future of the EU and the euro exists only if there is a change in political culture in Europe and politicians can adapt to making choices again. The US isn’t in that position yet, but it is unavoidable in the end and, from a neutral perspective, the Tea Party’s radicalism- superficial or not- gives the Republicans a definite edge at this stage.

30. November 2010 at 14:53

Yglesias thinks the Fed should supply the dollars Europe wants. Will they? Not if the Congressional crazed deflationists have any say in the matter.

http://yglesias.thinkprogress.org/2010/11/the-demand-for-dollars/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+matthewyglesias+(Matthew+Yglesias)

30. November 2010 at 16:23

OGT I am sure the banks and politicians grossly underestimated the amount of debt they were ultimately guaranteeing. Because the level of credit offered/debt created is not independent of whether it is guaranteed. Eliminating downside risk has an effect on behaviour: why is this hard? Yet, again and again, it seems to be so — think Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Think IMF’s “welfare for Wall St” …

30. November 2010 at 19:52

DeLong asks why all this is happening – that the government apparently doesn’t much care about 10% unemployment, and isn’t going to do much about it.

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/delong108/English

Good questions.

And personally I think the answer is the Obama does not give one sweet s**t.

1. December 2010 at 00:49

Scott

You admit to massively unsustainable supply-side problems like Fannie and Freddie and 99-week unemployment insurance. But then assure us not to worry, no matter what supply-side shocks or more common creeping supply-side frictions and inefficiencies, NGDP will also march on at the same “underlying” trend”.

How do you KNOW that the trend is always the same? How do you KNOW the 2002-2008 “trend” wasn’t above an underlying, new, lower trend growth?

I guess because you are a macroeconomist first and a microeconomist second, you KNOW these things, that us mere mortals are less sure about.

P.S. Am just back from Germany and their, consensus-driven, self-help, Swedish-like, response to this crisis is doing them just nicely now that other countries are finally getting their comeuppance for years of “above-trend” credit-financed NGDP growth. They are in no hurry to bail out the imprudent, debt-gorged periphery, but will in the end.

1. December 2010 at 01:03

Scott

You asked me on an earlier blog response why printing money was “cheating”. If individuals, corporates and banks wish to move to cash because they fear for the future, their investments, their counterparties, then why should a central bank print money to offset this natural market phenomenon?

Although you say you don’t believe in liquidity traps, you were merely saying you thought they could be solved – by printing money. You fear them badly. Once indviduals, corporates, banks, expect there to be no magic fairy (no Greenspan “put”), expectations will bring about the necessary adjustments and money will flow again.

1. December 2010 at 03:43

I am strong believer of a European Q.E program. ECB should start printing money just like the fed and here is why http://seekingalpha.com/article/239298-why-the-ecb-should-consider-qe

1. December 2010 at 06:44

Scott, have you seen this long Matt Stoller post via Yves Smith critiquing the “corrupt” Fed and how it does monetary policy? Provocative.

1. December 2010 at 07:41

James in London,

In your second paragraph, you expect monetary policy to change people’s behaviour i.e. central bank intervention prevents people making the “necessary adjustments”.

In your first paragraph, you regard people’s behaviour as a “natural market phenomenon”, as if people’s behaviour in the last two years was entirely independent of the deflationary monetary conditions.

If a central bank commits to a 2% target, people expect it to do what it takes to achieve that, and then it fails to meet that target, how is that a natural market phenomenon or a market phenomenon of any sort? Destabilising nominal conditions via setting expectations in private contracts/decisions and then not doing what it takes to meet them doesn’t sound like the market to me.

Consider if it was the other way around: if there was 10% inflation, would you say that the central bank should continue its monetary policy and not try to bring inflation down? After all, aren’t people’s reactions to an inflationary shock as much a “natural market phenomenon” as their reactions to a deflationary shock?

1. December 2010 at 08:07

W. Peden

I don’t agree Central Banks should target a 2% inflation rate, it is bound to fail. Central Banks just aren’t that smart and can never know enough. Scott’s target the forecast is even more comical as it would just lead players to game and arb those forecasts, prop traders aren’t fools, Goodhart’s Law would soon kick into action.

No macroeconomic manager can succeed as the macroeconomy does not really exist, certainly not in a way that it can effectively be managed. We live in a world of anarchic order that looks like it’s been planned, but it hasn’t been. Spontaneity rules, and governments more or less sticks its oar into the spokes and more or less makes things less good than they otherwise would have been.

Keep to a few good micro principles and leave well alone. No monetary policy is best policy. So, keep the money supply constant and let gentle (good) deflation work it’s magic. If there are shocks big enough to lead to a general loss of confidence and a shortage of money demand, as Scott and his friends fear, this will cure itself once people realise there is no magic wand solution of printing money. There is no liquidity trap (as a great economist once wrote).

1. December 2010 at 08:50

Again, I would ask again, how do you KNOW the 2002-2008 growth trend on the charts above we were not above a new, lower, trend – and thus needing a correction. The credit bubble was a very real, and huge, phenomenon, that led to hugely excessive (although, mostly unrealised at the time) risk-taking. The whole shadow banking system and related rapid growth in banking assets was a real phenomenon, causing massive misallocation of resources – and thus needing a correction. It’s not rocket science.

1. December 2010 at 11:14

James in London,

The question is not whether or not central banks should target 2% inflation.

The question is that, given that they have committed to such a target and individuals have made decisions that assume such a target, should central bankers deviate from this target at precisely the moment when a nominal shock has disrupted the extended order of society?

If the velocity of money increased substantially and a constant money supply target of, say, 5% per annum led to an inflation rate of 10%, would you still support keeping the money supply constant?

1. December 2010 at 13:35

OT, but worthy of Scott Sumner’s perusal and commentary:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704638304575636861053069680.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

Vernon Smith, Cato, Chapman, Nobel Prize winner, advovates QE2 to re-cap bak mortgages. Also notable that a “conservative” is not bashing Bernanke.

1. December 2010 at 14:18

W. Peden “If the velocity of money increased substantially and a constant money supply target of, say, 5% per annum led to an inflation rate of 10%, would you still support keeping the money supply constant?”

Apart from thinking a 5% per annum target insanely managerial of an unmaneagable “macro-economy”, if you asked me if money supply were stable and velocity increased 5% leading to a 5% inflation rate would I favour sticking to the stable money supply? Yes. Any misallocation from the increased-velocity-induced inflation would reverse in time.

Anyway, velocity of money circluation is a concept I really struggle with as a micro-economist. Predicting velocity of money and attempting to manage it are a bit like trying to predict and manage the weather.

1. December 2010 at 15:28

James in London,

The 5% figure was simply because it’s the classic number for central bank control of the money supply. A 5% or a 0% figure are identical in principle.

Anyway, I think you’re on the right lines if you’re willing to take the rancid (rising prices) and the sour (falling prices) with the sweet (considerable price stability over time). Then again, I’m a boneheaded monetarist.

I think the velocity of money is a straightforward concept. But you overestimate its predictability: predicting the weather is one thing, but predicting velocity is a mug’s game. However, I’m still not convinced that that negates the importance of controlling the money supply. It seems to me that, if we can’t control velocity at all, we can at least moderate the fluctuations of what can be controlled.

1. December 2010 at 16:11

“Hayek would have told the ECB to print more money”…

…but Mises and Rothbard would have screamed STOP THE PRESSES!

Readers should not (as I’m sure you don’t) confuse Hayekian pragmatism for Misesian logic.

1. December 2010 at 19:29

“Again, I would ask again, how do you KNOW the 2002-2008 growth trend on the charts above we were not above a new, lower, trend – and thus needing a correction.”

Ho doesn’t James. When push comes to shove, he really doesn’t have an answer.

But he also refuses to admit that this entire charade is about desperately trying to keep home prices from falling, so the banks don’t go insolvent.

But, Greenspan is a one note trumpet on that message – he’s perhaps the single man most likely to KNOW and BE WILLING to say whats going on – he’s playing catch up with his reputation before he dies.

Without rents, we’re at 1.9% CPI which is Benji’s target.

Fun Fact: over here, we’re talking about ending the Mortgage Tax deduction which would have a deep depressing effect on home prices – owning a big house will no longer be a tax shelter.

As such, we’re about to watch Sumner say we MUST PRINT MONEY to offset the negative effects of simplifying the tax code.

1. December 2010 at 20:14

@JimP:

Its not that they don’t care, its that they don’t care for the unemployed. Of course they care about unemployment, high unemployment is a great opportunity for them to implement their policy choices, and to find an excuse to give to their supporters (calling it a stimulus).

2. December 2010 at 07:39

Thanks JimP, I hope the Fed has learned it’s lesson, but I doubt it.

Bogdan, Thanks for the link–they are a long way from a US type government, (Thank God)

Wonks Anonymous, He’s wrong about expectations, they are usually ahead of reality.

Cameron. Thanks, I need to think about what that all means. Fed funds futures are forecasting both the economy, and also the Fed’s reaction to the economy. Those two variables must be disentangled somehow.

W. Peden, I agree with your comments on the UK situation.

Regarding the EU, the tight money policy of the ECB caused a public debt crisis that was going to eventually happen, to happen much sooner.

JimP, I agree with Yglesias. Or should I say he agrees with me? 🙂

Lorenzo, That’s a very good point about the effect of moral hazard.

JimP, It is puzzling that the elites seem so unconcerned about 9.6% unemployment.

James, You said;

“You admit to massively unsustainable supply-side problems like Fannie and Freddie and 99-week unemployment insurance. But then assure us not to worry, no matter what supply-side shocks or more common creeping supply-side frictions and inefficiencies, NGDP will also march on at the same “underlying” trend”.

How do you KNOW that the trend is always the same? How do you KNOW the 2002-2008 “trend” wasn’t above an underlying, new, lower trend growth?

I guess because you are a macroeconomist first and a microeconomist second, you KNOW these things, that us mere mortals are less sure about.”

It’s not a question of being an immortal, it is understanding the basic principles of macro. Talking about sustainable trends in NGDP growth is sheer gibberish. The Fed can set any NGDP trend it likes.

You said;

“You asked me on an earlier blog response why printing money was “cheating”. If individuals, corporates and banks wish to move to cash because they fear for the future, their investments, their counterparties, then why should a central bank print money to offset this natural market phenomenon?”

Why shouldn’t the Fed accommodate the public’s wish to hold more money? If they don’t, people will have to fight over who gets to hold an insufficient amount of base money–causing deflation.

Michael, I agree.

JTapp, I think “provocative” is being a bit generous. He is asking for a return to 1940s Keynesianism.

James, Goodhardt’s law has no relevance for my proposal, because I don’t favor using intermediate targets.

You said;

“Again, I would ask again, how do you KNOW the 2002-2008 growth trend on the charts above we were not above a new, lower, trend – and thus needing a correction.”

Again, it’s hard to debate macro with someone who keeps insisting on ignoring the distinction between RGDP (which is not controllable in the long run) and NGDP, which is.

Benjamin, Thanks for the Smith article. I think he focuses too much on housing, which is only about 5% of GDP.

Thanks leo, I used your comment in my new post.

Morgan, You said;

“Ho doesn’t James. When push comes to shove, he really doesn’t have an answer.”

All my suggestions that James doesn’t understand macro principles applies equally to you. I’m talking about NGDP, not RGDP. I must have said that 100 times to each of you.

And I’m not a ho, not that there’s anything wrong …

2. December 2010 at 08:27

[…] a commenter named Leo made this interesting observation: Readers should not (as I’m sure you don’t) confuse Hayekian […]

2. December 2010 at 09:34

Scott-

But debt on housing is an important part of bank portfolios…..and people’s nesteggs…

2. December 2010 at 09:40

Scott

What is the chart at the top of this blog? Why did you post it? You wanted to demonstrate NGDP was off-trend and needed to be brought back on trend. I am still wondering how you KNOW what the trend really is, or should be?

Who knows what real GDP should be? If supply-side problems/bubbles bursting/shocks should cause Real GDP to fall 10% from where they had got to, why paper over the correction with pumping the money supply? Because you think the market can’t do it without a load of monetary grease? But what is your evidence? If people (the market) don’t expect the monetary grease then they will get on with the job themselves all the more quickly.

Macro principles = politics. Or rather macro principles = fear of deflation. You don’t believe the people (the market)can adjust automatically, spontaneously, anarchically to shocks without relying on our immortal, all-knowing central bankers (aka central planners) to add just the right amount of money to the money supply, at just the right time, and then withdraw just the right amount of money, at just the right time.

Because they can’t achieve this feat, no central banker (aka central planner) can, you will blogging for ever. (Even though this will still be a fun thing in which to participate.)

2. December 2010 at 14:08

And again, he doesn’t KNOW.

He won’t specifically answer questions either. I’ve asserted routinely we should use 2001-2004 to determine new normal growth.

After the web bubble, when we had growth, but before the housing bubble. Scott doesn’t give an answer, he just asked WHY I chose that time, like my answer isn’t obvious: it happens when there is no bubble.

—-

Scott, perhaps you should place a link at the top of your site that shows in multiple ways:

Historical NGDP

Historical GDP

Inflation

And forget unemployment.

ALSO: if throwing out Mortgage Tax Credit causes homes prices to fall, are you going to say they are returning to normal (sans subsidy), or are you going to pretend there is deflation as rents plummet?

4. December 2010 at 09:52

Benjamin, I agree that the housing crisis helped trigger the banking crisis. But right now I don’t think banking problems are holding back the economy, lack of AD is. I suppose you are right in the sense that if AD doesn’t improve, there could be more defaults and the banking crisis could flare up again.

James. I don’t know the precise trend in NGDP, but the level is lower than two years ago, so I firmly believe recent growth has been well below trend. I’m guessing the trend is around 4% nominal growth in Europe. If the ECB felt NGDP was far too high in early 2008, they would have aggressively tried to reduce it. But they didn’t, rather they passively let it fall. That looks like a policy mistake to me–letting NGDP fall during a severe banking crisis.

Morgan, You don’t determine trend NGDP, the Fed does. They’ve implicitly been targeting around 5% growth. That may be too high, but a financial crisis is not time to downshift to the lower trend line you think appropriate.

7. December 2010 at 07:21

Scott,

Didn’t know where else to put this (that I’m half Polish of course has nothing to do with this). 😉

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/07/business/global/07zloty.html?_r=1&hpw

The fact that Poland had no recession (or financial crisis) makes it absolutely unique among EU members. And so it would seem that printing zloty worked. (And I have the actual numbers. Poland depreciated more than any EU member with its own currency during the crisis.)

P.S. If you read the article you’ll note that Poland ranks 70th out of 183 countries for ease of doing business, according to the World Bank. So it certainly wasn’t their neoliberal economic policies that got them through the short term unaffected. However, an improvement in those policies might help their long term outlook.

8. December 2010 at 18:34

Mark, Thanks for that info, I agree about Poland.

25. December 2010 at 11:47

[…] is commenter Cameron: Scott, I was actually able to find fed fund futures reaction to the December 2007 25 (rather than […]

7. March 2011 at 04:52

[…] Irish forbearance, what was it good for? – FT Alphaville What lies in Greek RMBS – FT Alphaville Hayek would have told the ECB to print more money – Money […]

6. April 2011 at 04:31

[…] This is not normal ECB tightening – FT Alphaville Eurozone interest-rate hindsight – FT Alphaville Hayek would have told the ECB to print more money – Money […]