No we can’t

I’m so depressed I just want to give up on this pointless crusade, but I suppose I’d better say something about Bernanke’s “pep talk” today in front of Congress. In the Q&A he argued that “no one” can dispute the aggressive nature of monetary policy today:

“Senator I think it’s important to preface the answer by saying that monetary policy is currently very stimulative as I’m sure you are aware. We have brought interest rates down close to zero, we have had a number of programs to stabilize financial markets, we have language which says we plan to keep rates low for an extended period. And we have purchased more than a trillion dollars in securities.

“So certainly no one can accuse the Fed of not having been aggressive in trying to support the recovery. That being said, if the recovery seems to be faltering then we will at least need to review our options.

I guess that makes me “no one.” In the 1930s everyone seemed to think Fed policy was expansionary. They cut rates close to zero, they dramatically increased the monetary base, they encouraged banks to hold on to more reserves. Hoover set up a fund to help the banking system. I’m not disputing that the Fed has done more this time. But Bernanke himself admitted that we now know Fed policy was actually contractionary during the 1930s. By what benchmark can the economics profession say it was contractionary then, but is highly expansionary now? I’ve asked the question 100 times of my fellow economists and still haven’t received an answer.

The broader aggregates? OK, I admit they fell in the 1930s. But I thought the monetary aggregates were discredited as policy indicators in the 1980s? Now you have economists who had dismissed monetarism as a washed up doctrine suddenly clinging to the aggregates as the one piece of evidence that money was easier this time than in the 1930s. This crisis makes economists look like a bunch of atheists who suddenly accept the Lord on their deathbed. Well it’s too late for that, even M3 is falling now.

Here’s the problem. The Fed’s “effort” only matters if one policy stance is more costly than another. That may be true for fiscal policy, but it isn’t true of monetary policy, at least for any plausible policy stance. Krugman talks about how massive QE could expose the Fed to some price risk. But there are three things the Fed could do with minimal price risk; lower the interest rate on reserves, set a price level target, and do several trillion in QE with T-bills and short term T-notes. In practice, the Fed would never go beyond those three steps, so it makes no sense to talk about the Fed having “given it the old college try.” The correct metaphor is a steering wheel. Is the steering wheel set at a position where they expect to reach their goal? That’s the only sense in which one can talk about “easy” or “tight” money.

Here’s what Bernanke says about the prospects for reaching their goals:

The unemployment rate is expected to decline to between 7 and 7-1/2 percent by the end of 2012. Most participants viewed uncertainty about the outlook for growth and unemployment as greater than normal, and the majority saw the risks to growth as weighted to the downside. Most participants projected that inflation will average only about 1 percent in 2010 and that it will remain low during 2011 and 2012, with the risks to the inflation outlook roughly balanced.

Bernanke’s lucky that Congress doesn’t have a clue as to how to interpret Fed-speak, because he is basically saying the following:

1. The Fed has reduced its implicit inflation target below 2%, indeed below even 1.5%.

2. The Fed sees more downside risk on jobs, but puts a zero weight on jobs in its policy deliberations.

Bernanke has frequently suggested that the dangers of missing the inflation target are not symmetrical, with deflation being a far more serious problem than modestly higher inflation. If the Fed is forecasting 1.25% inflation in 2012, and if they also think the inflation risks are balanced, then we know the hawks have won. Especially given the downside job risks. Last year Janet Yellen said “we should want to do more.” Today Bernanke basically said the Fed has options, but doesn’t want to do more. As I noted earlier, I suspect his actual views are slightly more dovish, but he may feel obligated to paper over differences at the Fed when testifying to Congress.

Oh, and one other thing. Bernanke told Obama that he better plan on running for re-election in 2012 with the same unemployment rate George Bush faced in 1992. You remember, the Bush that presided over a big foreign policy success in the Gulf War, and then got 38% of the vote two years later.

Bernanke also noted that the Greek crisis had increased the demand for dollars, causing NGDP growth forecasts to fall below levels expected in April:

One factor underlying the Committee’s somewhat weaker outlook is that financial conditions–though much improved since the depth of the financial crisis–have become less supportive of economic growth in recent months. Notably, concerns about the ability of Greece and a number of other euro-area countries to manage their sizable budget deficits and high levels of public debt spurred a broad-based withdrawal from risk-taking in global financial markets in the spring, resulting in lower stock prices and wider risk spreads in the United States.

Oddly, he did not indicate any Fed plans to respond to the increase in demand for dollars. Instead, the Fed is content to see the Greek crisis further depress the already pathetically weak NGDP growth forecasts. But they do plan to keep an eye on the situation:

We will continue to carefully assess ongoing financial and economic developments, and we remain prepared to take further policy actions as needed to foster a return to full utilization of our nation’s productive potential in a context of price stability.

And what might those further actions be? Returning to the Q&A link above:

“We have not fully done that review and we need to think about possibilities. But broadly speaking, there are a number of things we could consider and look at; one would be further changes or modifications of our language or our framework describing how we intend to change interest rates over time “” giving more information about that, that’s certainly one approach. We could lower the interest rate we pay on reserves, which is currently one-fourth of 1%. The third class of things has to do with changes in our balance sheet and that would involve either not letting securities run off “” as they are currently running off “” or even making additional purchases.

Here’s how to tell if the Fed is serious, if and when it moves. If they take one of those three steps, it will merely be a desultory action aimed at mollifying the markets. If they are serious, and really want to turn around market sentiment, then they will use the multi-pronged approach I recommended last year; eliminate interest on reserves, major QE, and some sort of quasi-inflation targeting language. As Bernanke indicated, the best we could probably hope for regarding inflation targeting is a vague mention that rates would be left low until some collection of macro indicators rise much more substantially—i.e. no early exit. Those three steps might not be enough for a fast recovery, but it would almost certainly get things moving again.

At a personal level I do get some satisfaction from seeing Bernanke finally mention reducing the IOR as a possible expansionary policy option. My very first blog post (after the intro) was on this issue. Even earlier I mentioned it in a short paper in The Economists’ Voice. Even before I set up my blog, people like Jim Hamilton were warning of the contractionary nature of IOR. But I do think I pushed the idea a bit further, especially with my suggestion of negative rates on ERs. (An idea later adopted in Sweden, but with lots of loopholes.) In the early days I took a lot of grief for focusing on this issue, although I always thought other steps like inflation/NGDP targeting were more important. But with Bernanke mentioning it as a policy option, I think the Hall/Hamilton/Sumner view that IOR was contractionary has been vindicated. Bernanke would not mention reducing IOR as one of three possible expansionary steps, if the program itself was not contractionary.

Despite this minor personal vindication, today fills me with gloom. It will be interesting to hear what you commenters think. How about it JimP? Did Bernanke exhibit the sort of “Rooseveltian Resolve” that (in 1998) he insisted the Japanese needed in order to get out of their Great Recession? Did he show the “yes we can” spirit? The Rooseveltian/Kennedyesque/Reaganesque determination that we won’t put up with high unemployment for as far as the eye can see? Or did he blink?

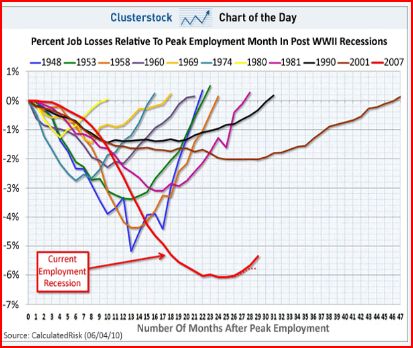

PS. Yes, there might be some “recalculation” problems out there. But how can we know that without first boosting NGDP growth, which is currently only one half the pace of the recovery from the 1982 recession?

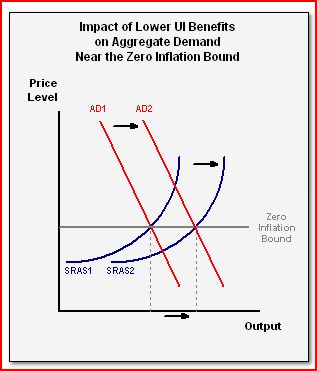

Update: Torgeir Hoien has a nice piece on monetary policy at the zero rate bound.