Why level targeting?

I’ve done a number of posts advocated level targeting, but many readers remains skeptical. Here I’ll try to provide a bit more intuition in support of the idea.

Let’s think about a model with NGDP growth rate targeting at 4%/year. Assume that once every 5 years the central bank makes a mistake and NGDP moves 4% off target (i.e. 0% or 8% growth.) Then they let bygones be bygones and establish a new NGDP trend line from that point forward. Also assume that half of the errors are in an expansionary direction and half are in a contractionary direction. Thus once in every 10 years you get a recession, and once in every 10 years you get overheating and high inflation.

At first glance, it seems like switching to level targeting would be a step backwards. Now you’d see periods of declining NGDP occurring once every 5 years, not once every 10 years. This would occur when there was a contractionary mistake, and it would also occur when the Fed had to correct an expansionary mistake and get back to the old trend line. Twice as many recessions! That sounds bad.

I see two reasons why level targeting would actually produce better results than growth rate targeting. I’m going to focus on the issue of correcting overshoots, as many opponents of NGDP level targeting (including Jay Powell) have no problem with correcting undershoots.

[BTW, I am not suggesting we now correct the recent overshoot, because we don’t have a NGDPLT policy in place. I’ll explain the distinction later, but this is about setting up a new regime when the economy is currently in equilibrium, say back in 2019.]

I believe that NGDP growth targeting proponents overestimate the cost of correcting overshoots for two reasons:

1. They overlook the fact that level targeting would make overshoots (and undershoots) much smaller in the first place.

2. The overlook the fact that the pain of correcting NGDP overshoots from a booming economy is much smaller than the pain of an equivalent reduction in NGDP starting at trend.

Both of these conjectures require some explanation:

Suppose that in mid-2021, the Fed had announced that any overshoot of NGDP would be erased as quickly as possible, using a tight money policy to bring NGDP back to the trend line. In that case, as NGDP started heading for an overshoot in late 2021, interest rates (relative to the natural rate) would have soared much higher, in anticipation of a future tight money policy to bring NGDP back to trend. BTW, most of the contractionary “work” would have been done by lowering the natural interest rate, not raising the actual policy rate.

Instead, the Fed held their policy rate far below the natural rate in late 2021, causing NGDP to dramatically overshoot the pre-Covid trend line.

So yes, under level targeting there’d be twice as many periods of declining NGDP as under growth rate targeting, but they’d be correcting much smaller overshoots—say 1% or 2%, not 4% as with growth rate targeting. As an aside, many New Keynesian models suggest that changes in the current level of aggregate demand are heavily influenced by changes in future expected levels of aggregate demand. In these models, an expectation of future tightening makes money tighter right now. Thus under level targeting, the market helps to stabilize the economy. This may be one reason why New Keynesians such as Michael Woodford have advocated NGDPLT.

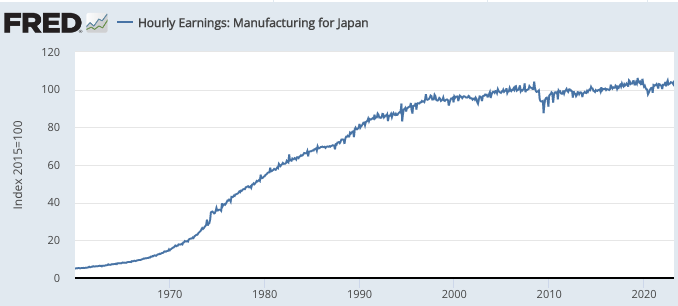

In addition, the corrections would be much less painful, even for any give reduction in NGDP. To see why, we need to consider the components of NGDP growth. Recall that NGDP is also gross domestic income. Overshoots of NGDP can be decomposed into overshoots of profits, hours worked, and nominal hourly wages.

When overshoots are corrected quickly, almost all of the action takes places with profits and hours worked. During the period of correction, the economy moves from excess profits and higher than nominal hours worked back to normal profits and normal hours worked. That’s not painful!

What would be painful? Suppose the excessive monetary stimulus were persistent. Eventually, those sticky nominal wages would begin rising. Output would return to the natural rate. In order to reverse these excessive wage gains, you’d probably need to create “slack” in the economy, i.e. higher unemployment. That doesn’t mean a softish landing is impossible, but it’s far more difficult than under level targeting.

The best time to correct the policy mistake is right away, before the NGDP overshoot spills over from profits and hours worked into higher nominal hourly wages. This sort of correction will be much less painful than a reduction in NGDP starting from trend, which would likely create a recession.

Some commenters ask me, “Given that you favor level targeting, what should the Fed do now?” To begin with, the Fed should only do NGDP level targeting if it has already announced a very specific NGDP level target. It has not done so, and hence it would now be inappropriate to return to the pre-2020 trend line. We don’t even know what trend line they would have chosen if (back in 2019) they had opted for NGDP level targeting.

So that’s all a moot point. If the Fed is targeting 2% inflation then they should target 2% inflation. I’m not happy with the target—I’d prefer NGDPLT—but if that’s the target then take it seriously. (Obviously the dual mandate allows some flexibility, but at a minimum the long run inflation rate needs to average 2%.)

Some people still fail to see that monetary policy was too expansionary during 2022. Admittedly, by that time it was too late to return to the old trend line, but we should at a minimum have reduced NGDP growth to the old trend line. Instead, the economy rose further and further above trend and the labor market continued to be wildly overheated. In 2022, we could have had a tighter monetary policy, lower inflation, and a better functioning labor market.

If I switch from eating three donuts every breakfast to two donuts every breakfast, that certainly doesn’t mean I’m dieting. Money was too expansionary in 2022, even if NGDP growth slowed late in the year. Growth was still far too rapid.

[BTW, the real consumption figures from 2022 are highly suspect, as they don’t account for the horrendous decline in the quality of service faced by consumers of things like travel and hotels. As we return to normal, the rate of productivity growth rate will be understated.]

PS. Here’s a shorter version of this post. Macroeconomic instability is caused by fluctuations in the growth rate of the aggregate nominal wage rate. Level targeting stabilizes nominal wages more effectively than growth rate targeting.