Williamson on monetary policy and interest rates

In the past, Stephen Williamson has attracted some fierce criticism for his views on the relationship between money and interest rates, specifically some posts that seemed to deny the importance of the “liquidity effect.” Nick Rowe and others criticized Williamson for seeming to suggest that a Fed policy of lowering interest rates would actually lower the rate of inflation–via the Fisher effect. Williamson has a new post that seems to have somewhat more conventional views of the liquidity effect, but still emphasizes the longer term importance of the Fisher effect:

If the central bank experiments with random open market operations, it will observe the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate moving in opposite directions. This is the liquidity effect at work – open market purchases tend to reduce the nominal interest rate and increase the inflation rate. So, the central banker gets the idea that, if he or she wants to control inflation, then to push inflation up (down), he or she should move the nominal interest rate down (up).

But, suppose the nominal interest rate is constant at a low level for a long time, and then increases to a higher level, and stays at that higher level for a long time. All of this is perfectly anticipated. Then, there are many equilibria, all of which converge in the long run to an allocation in which the real interest rate is independent of monetary policy, and the Fisher relation holds.

Before discussing Williamson, let me point out that back in 2008-09, 99.9% of economists thought the Fed had eased policy, and that the deflation of 2009 occurred in spite of those heroic easing attempts. That 99.9% included the older monetarists. Only the market monetarists and the ghost of Milton Friedman insisted that money was tight and that interest rates were falling due to the income and Fisher effects. I’d like to think that Williamson agrees with us, but of course he’d be horrified by the specifics on the MM model, indeed he wouldn’t even recognize it as a “model.”

Williamson continues:

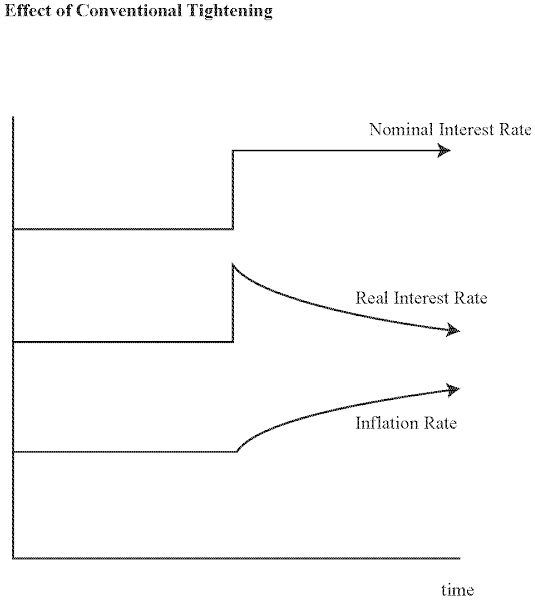

A natural equilibrium to look at is one that starts out in the steady state that would be achieved if the central bank kept the nominal interest rate at the low value forever. Then, in my notes, I show that the equilibrium path of the real interest rate and the inflation rate look like this:

Is that really monetary tightening? After all, inflation rises. Here’s the very next paragraph by Williamson:

There is no impact effect of the monetary “tightening” on the inflation rate, but the inflation rate subsequently increases over time to the steady state value – in the long run the increase in the inflation rate is equal to the increase in the nominal rate. The real interest rate increases initially, then falls, and in the long run there is no effect on the real rate – the liquidity effect disappears in the long run. But note that the inflation rate never went down.

The scare quotes around “tightening” suggest that Williamson is also skeptical of the notion that tightening has actually occurred. Indeed inflation increased, then policy must have eased. However to his credit he recognizes that “conventional wisdom” would have viewed this as a tightening. Nonetheless the final part of the paragraph has me concerned. Williamson refers to the disappearance of the liquidity effect, but in the example he graphed there is no liquidity effect, as the rise in interest rates was not caused by a tightening of monetary policy. If it had been caused by tighter money, inflation would have fallen.

So how can the graph be explained? As far as I can tell the most likely explanation is that at the decisive moment (call it t=0) the equilibrium Wicksellian interest rate jumps much higher, and then gradually returns to a lower level over the next few years. And the central bank moves the policy rate to keep the price level well behaved. I suppose you might see this as being roughly the opposite of the shock that hit the developed economies in 2008, except of course it was more gradual.

Suppose there had been no change in the Wicksellian equilibrium rate, and the central bank simply increased the policy rate by 100 basis points, and kept it at the higher level. In that case, the economy would have fallen into hyperdeflation. When you peg interest rates in an unconditional fashion, the price level becomes undefined.

Is there any other way that one could get a path like the one shown by Williamson? Could the central bank initiate this new path? Maybe, at least if you don’t assume a discontinuous change in the interest rate, followed by absolute stability. To explain how you could get roughly this sort of path lets look at the reverse case.

Suppose the Fed had been increasing the monetary base at about 5% a year for many years, and the markets expected this to continue. This led to roughly 5% NGDP growth. The markets assumed the Fed was implicitly targeting NGDP growth at about 5%. But the Fed actually also cared about headline inflation, which suddenly rose higher than desired (due to an oil shock.) The Fed responded by holding the base constant for a period of 9 months. (For those who don’t know, so far I’ve described events up to May 2008.)

This unexpectedly tight money turned market expectations more bearish. As expectations for NGDP growth became more bearish, the asset markets fell and the Fed responded by cutting interest rates. And since inflation did not immediately decline, real short term rates also fell (still the mirror image of the Williamson graph.) BTW, we know that even 3 month T-bill yields FELL on the news of policy tightening at the December 2007 FOMC meeting. Williamson would have approved of that market reaction!!

Normally the Fed would have realized its mistake at some point, and monetary policy would have nudged us back onto the old path. In this case, however, market rates had fallen to zero by the time the Fed realized its mistake. And the Fed was reluctant to do unconventional stimulus. There was a permanent reduction in the trend rate of NGDP growth, as well as nominal interest rates. This showed up in lower than normal 30-year bond yields. The process played out even more dramatically in Europe (and earlier in Japan.)

I do have one quibble with the Williamson post. He seems too skeptical of the claim that the ECB recently eased policy. But before I criticize him let me say that I find his error much more forgivable than the conventional wisdom, which views low interest rates as easy money.

Williamson points out that the ECB recently cut rates, and that if the ECB leaves rates near zero for an extended period of time, then inflation is likely to stay very low, as in Japan. All of this is correct. But I think he overlooks the fact that while the overall policy regime in Europe is relatively “tight”; the specific recent actions taken by the ECB most definitely were “easing.” We know that because the euro clearly fell in the forex markets in response to that action.

I think this puzzles a lot of pundits. It’s very possible for central banks to take relative weak actions that are by themselves expansionary, even while leaving the overall policy stance contractionary, albeit a few percent less so than before. That’s the story of the various QE programs in America.

I encourage all bloggers to never reason from a price change. Do not draw out a path of interest rates and ask what sort of policy it is. First ask what caused the interest rates to change—the liquidity effect, or the income/Fisher effects?

PS. Of course I agree with most of the Williamson post, such as his criticism of “overheating” theories of inflation.

HT: TravisV

Tags:

13. September 2014 at 08:59

Central banking prevents partially ignorant of each other populations from learning and improving themselves monetarily. It is not a coincidence that personal finance knowledge is relatively lacking.

Private property provides the invaluable benefit of enabling individuals to experience the full costs if their monetary choices. But with socialist money, these costs are of course socialized, thus preventing people from learning the connections between choices and costs.

13. September 2014 at 09:02

Never reason from a spending change.

13. September 2014 at 10:01

Fascinating post!

I’m not sure I provided the link to this one but I’ll take the credit anyway…..

13. September 2014 at 10:21

Fun Fax! Who can write the one-sided Laplace transforms? (… making a few assumptions, I left what I think is the right answer on Williamson’s blog)

13. September 2014 at 11:56

Heart…right place…

http://www.voxeu.org/article/making-vox-accessible-undergraduates-voxeu-course-companions

‘The idea behind the VoxEU Course Companions is simple. Economics can seem complex and mysterious to students who have just started studying it. As exams begin to loom, textbook theories can remain abstract and elusive, detached from economic and political reality. By providing a recent and real-world discussion of the material in each chapter, the Course Companions should help make the material more concrete, more real.

‘Vox columns analyse economic phenomena as they happened while applying and comparing the suitability of competing economic theories. The hope is that students will learn better, and remember their lessons longer when they recognise terms and theories from lectures in current discussions. Vox columns provide good examples of leading economists’ thought-provoking perspectives on arguments that come up time and again in exam-style questions.’

Now if we just had something for the professors.

13. September 2014 at 13:26

Utter non-sense. The man obviously doesn’t trade bond futures nor has watched or studied the financial markets.

13. September 2014 at 13:27

If you went to Chicago then you must be watching money. M1’s roc has fallen from 14 to 4 percent from July to Sept. Flash crash due 10/1/2014

13. September 2014 at 13:34

flow5:

Investors use more than just M1 to bid securities.

M2 is better. It has only modestly declined from 6ish to 5ish.

13. September 2014 at 13:35

So where does Williamson think rates are headed? If he can’t predict, nothing he says is meaningful.

13. September 2014 at 13:41

M2 is better? Major, you write too much about everything you know nothing about. The ratio of demand drafts clearing thru transaction based accounts relative to non-m1 deposit classifications is 500 to < 3.

I am the greatest market timer in history.

13. September 2014 at 13:54

Nonetheless the final part of the paragraph has me concerned. Williamson refers to the disappearance of the liquidity effect, but in the example he graphed there is no liquidity effect, as the rise in interest rates was not caused by a tightening of monetary policy. If it had been caused by tighter money, inflation would have fallen.

Well, that seems circular, or at least unproductive. Williamson is not defining the liquidity effect as “tighter money” causing anything. He is trying to show how raising actual and expected nominal interest rates through OMOs can cause real interest rates to rise in a way that would not be predicted by the Fisher Effect alone. Whatever is allowing this departure from the Fisher Effect and pushing bond price down and real interest rates up despite higher expected inflation is a “liquidity effect” in his model.

So how can the graph be explained? As far as I can tell the most likely explanation is that at the decisive moment (call it t=0) the equilibrium Wicksellian interest rate jumps much higher, and then gradually returns to a lower level over the next few years.

I don’t think that’s at all what’s going on here. In my opinion, Williamson is still stuck on the same problem, the original Kocherlakota mistake. Yes, he now introduces a “liquidity effect” into his Fisher equilibrium, but the key is still just the primacy he places on expectations of the Fisher equilibrium magically holding instead of exploding.

Like this: The Fed raises rates and is expected to keep them up. All agents know that if the Fed were able to do this, it must mean that inflation is going to be higher in the long run, because in the long run it is the Fisher Effect and not ephemeral liquidity effects that controls nominal rates and neutrality holds. This Fisher Expectation dominates the possible equilibria that result and the impact of the liquidity effect is thus heavily constrained by these equilibria. So you don’t have some big jump in the Wicksellian real rate as you suggest. What you have is a model of expectations that inherently forces inflation and bond prices back to a very constrained equilibrium after a temporary departure caused by some limited friction (in this case, segmented markets). Thus the temporary rise in the real rate above the Wicksellian rate might cause a little damage but is ultimately anchored back to parity by the Fisher expectational equilibrium.

Think of a world in which Congress announced a law that all interest rates would rise to 100% for five minutes to honor Derek Jeter. I see that as the main “liquidity effect” in Williamson’s model in that it is not capable of doing what really matters most about liquidity effects: potentially exploding the expected Fisher equilibrium.

13. September 2014 at 14:25

flow5,

“So where does Williamson think rates are headed? If he can’t predict, nothing he says is meaningful.”

You should know by now that blogger/economists don’t make a lot of concrete predictions (on their blogs anyway). Especially ones in which they say the equivalent of:

“If by 2017 X isn’t within Z of Y, then that’s very good evidence that I’m wrong. I won’t be adding epicycles to defend my model from reality. Instead I’ll admit that my core economics hypotheses are likely invalidated. It’ll be back to square one for me!… either that or I’ll just take up gardening.”

Understandable. Why take that kind of professional risk if you don’t have to? What’s the upside if none of your competitors are doing it? For that kind of thing you probably have to go to outsiders, whose day jobs won’t be affected if reality falsifies their core theoretical ideas. Shoot, how many econo-bloggers (professional or otherwise) are you aware of who would ever publicly spell out precisely what sets of future data would falsify their core ideas, let alone a particular model derived from them? 😀

13. September 2014 at 15:05

… sorry, I can’t resist razzing the econo-bloggers a little bit sometimes: even though I do really like them deep down. But if what I don’t see (much of) out there is as rare as it appears to me to be, then the field is wide open!! An aspiring econo-blogger, in possession of a large pair of cojones, might go for it and repeatedly put said cojones on the chopping block, and let reality take swing after swing at them. Lol. Now the big question is would said aspiring blogger garner respect or derision from his fellow bloggers? Would it matter if said cojones were still attached? (Lady econo-bloggers: I apologize for my sexist imagery: I don’t mean to exclude you here. Everyone else: I just plain apologize for my imagery altogether.)

13. September 2014 at 15:46

I am puzzled….where is QE and IOR in the Williamson model? Going forward, these may become the most important monetary policy tools. My guess is interest rates and pancakes are kin for a couple decades…so the discussion now is QE…

13. September 2014 at 19:32

TravisV, One degree of separation.

dlr, You said:

“Well, that seems circular, or at least unproductive. Williamson is not defining the liquidity effect as “tighter money” causing anything.”

I’m not quite sure what this means. I don’t think I said he “defined” the liquidity effect. Everyone agrees as to what the term ‘liquidity effect’ means, they simply disagree as to whether it exists.

He said:

“The real interest rate increases initially, then falls, and in the long run there is no effect on the real rate – the liquidity effect disappears in the long run.”

Which is a strange thing to say after showing a graph that contains no liquidity effect at all.

Tom, I partly agree, although I’ve made lots of predictions, and pointed to outcomes that would falsify my theories.

Then there are those Keynesian economists who make predictions and then later deny making them.

14. September 2014 at 08:19

Williamson’s analysis is historically wrong. You can’t measure the impact of current open market operations on interest rates without knowing where the rates-of-change in money flows (both proxies for real-output and inflation) are headed.

And:

FRB-NY’s website on the aggregates: “Chairman Greenspan added, ‘The historical relationships between money and income, and between money and the price level have largely broken down, depriving the aggregates of much of their usefulness as guides to policy. At least for the time being, M2 has been downgraded as a reliable indicator of financial conditions in the economy, and no single variable has yet been identified to take its place.’ ”

But Greenspan was vacuous. Nothing’s changed in over 100 years.

14. September 2014 at 08:26

You can moderate my comments all you want. That won’t change the fact that I’m the only one in the world who picked the bottom and top in bonds in the 31 year interest rate bull market.

14. September 2014 at 14:37

The Williamson graph is consistent with a conventional textbook macro model where there is a sudden, unanticipated fall in the money supply at t=0, followed by higher money growth for t>0 than for t0.

The model I have in mind assumes (1) sticky or slowly adjusting prices in the short run, (2) long-run money neutrality, (3) real money demand that is a function of real output and the nominal interest rate, (4) inflation expectations that equal actual inflation, and (5) output growing at an exogenous, steady rate. For more realism, we could modify (5) to allow short-run output fluctuations that are a negative function of the real interest rate. Then a recession occurs at t=0 and recovery follows.

Williamson’s graph is titled “Effect of Conventional Tightening.” His “conventional tightening” is apparently a permanent increase in the nominal interest rate. But a fall in the money supply followed by permanent faster growth, which generates his graph in a conventional model, is not what I would define as conventional tightening.

14. September 2014 at 18:32

The end of my first paragraph did not paste properly, omitting a symbol and cutting off two sentences. Here’s the first paragraph again – no symbols – correct now I hope:

The Williamson graph is consistent with a conventional textbook macro model where there is a sudden, unanticipated fall in the money supply at t equals 0, followed by higher money growth for t greater than 0 than for t less than 0. The standard liquidity effect is seen at t equals 0. Higher inflation offsets it for t greater than 0.

15. September 2014 at 07:48

“A natural equilibrium to look at is one that starts out in the steady state that would be achieved if the central bank kept the nominal interest rate at the low value forever.”

I have a whole bunch of problems with this…

Why would there be an equilibrium? Why would the market reach a steady state. I don’t think it would if the Fed were to be completely passive.

If the central bank holds rates at an artificially low rate indefinitely, I would expect rising inflation, falling real rates, which would lead to accelerating inflation.

There is more than one rate. There is a continuum of rates. The central bank only targets one of them, and that anchors the short end of the yield curve.

The market rate assumes that the central bank does react to new information. If the central bank were completely frozen, I have no clue what that would do to market rates.

The rate targets and inflation establishes an unstable system. But the Fed’s ability to react keeps it from spinning out of control.

15. September 2014 at 16:18

flow5:

You are confused about the monetary system. It doesn’t make a lick of difference what the ratio is between “transaction based accounts and non-M1 deposits”. If M1 growth ceases, then if M2 keeps rising investors have no less money to buy securities.

About 6 months to a year prior to the stock market crash of 2008, the M1 growth had already long since collapsed, and yet the stock market was still being bid up because investors tapped into their non-M1 deposits as the credit crunch intensified.

M2 is in fact better than M1, but it is still not perfect either.

15. September 2014 at 19:05

David, Interesting, but that can’t be a plausible explanation for any real world outcomes. And I thought he was trying to explain actual movements in interest rates in recent years.

16. September 2014 at 08:18

Good post Scott. Nothing to add.

17. September 2014 at 09:27

It’s hard to take a guy like Williamson seriously when he draws a graph like that. Okay, maybe the problem is that as an engineer, I know something about control theory and Williamson doesn’t. So he writes down a relationship between nominal rates and inflation, assuming real rates are anchored for some reason. Here is the problem. When you consider a system that can be described as a set of equations, just because you can find a set of values of system variables that satisfy all those equalities, doesn’t mean you will ever reach that equilibrium. Because it might be unstable!

I though economists understood this kind of thing, but apparently Williamson does not. He explicitly acknowledges that all his short term feedback (the liquidity effect) implies that the system will be moving away from the mathematical equilibrium that he believes to exist, but because that mathematical equality exists, he assumes that the system will eventually get back to that state, through the magic of long term expectations I suppose. Well, that’s a pretty pathetic basis for making an argument about monetary policy.

17. September 2014 at 12:33

mpowell, then you should be able to solve my “Fun Fax” above.

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=27538#comment-364640

Also, here’s a physicist’s take:

http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2014/09/theories-of-inflation-and-european.html?showComment=1410904537523#c2330331953765889814