Monetary equilibrium: Reply to Nick Rowe (and Bill Woolsey and Saturos)

Nick Rowe quotes me in a comment section (first paragraph), and responds (second paragraph):

Scott: “2. I assume the market for the MOA is in equilibrium (in terms of the MOE.) And in that case I’m pretty sure that I am right. A huge rise in the demand for gold makes the silver price of gold soar. That reduces the stock of MOE when priced in MOA terms. Since goods are priced in MOA terms, that’s very deflationary. QED?”

We are on the same page. I would say it differently. ‘A huge rise in demand for gold makes the silver price of gold soar, which reduces the real stock of MOE when priced in MOA terms, which creates an excess demand for MOE/excess supply of all other goods that have sticky prices, which is a recession’.

Thank God we are on the same page. For those who have trouble following, I’m going to switch from silver to Zimbabwe dollars, as in my earlier post. I’ll do an example where Nick and I agree, and then discuss the disagreement. Suppose Zimbabwe goods are priced on gold terms, and a strange phenomenon causes 1/2 of all the gold in the world to disappear. The equilibrium price level and NGDP will fall in half. The value of gold (in terms of goods) will double. If gold had been used as money, the amount of gold coins would have fallen in half. If we assume prices are very sticky in the short run, then the real stock of gold money would initially fall in half. If we instead assume that Z$s are used as a (medium of exchange) MOE, then the Z$ price of gold would double. This means that if the supply of Z$ (the MOE) was unchanged in nominal terms, it would fall in half in real terms, or gold terms. (Remember, real terms and gold terms are the same in the short run, as we hold goods prices in gold terms constant in the short run, and gold is the medium of account (MOA.)

I claim that if the supply of gold fell in half, and gold is the MOA, then the long run equilibrium price level and NGDP will fall in half. In the short run wages and prices are sticky, so this shows up as less real output. There was no change in the number of Z$s in circulation, so the MOE was not responsible for the recession.

Nick would say that the increased demand for MOA did start the ball rolling, but what actually caused the recession was the effect it had on the MOE. And even though it did not reduce the number of Z$s by one iota, it did reduce the real quantity of MOE, which led to fewer purchases, and a recession (because prices are sticky.)

Nick (and Bill and Saturos) see things from a disequilibrium perspective. More or less money puts the money (MOE) market into disequilibrium, and this gets resolved via a change in aggregate spending. The change in aggregate spending has effects on both prices and output, because wages and prices are sticky. Indeed we all agree on that last point, so let’s explore whether this is a case of disequilibrium in the money market, or elsewhere.

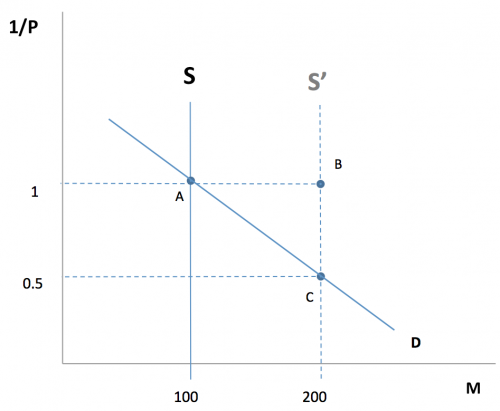

Consider this famous diagram of the money market:

The classic thought experiment for demonstrating the quantity theory is to double the money supply, while holding the real demand for money unchanged. In the long run you go from A to C, and the price level doubles to push the nominal demand for money in line with the newly enlarged nominal supply of money. In the short run prices are sticky, and you go to point B. I believe that point B is what my opponents call “monetary disequilibrium.” The money supply is too high to provide equilibrium at the current price level. I claim that at point B the labor market (and perhaps goods market) is in disequilibrium, but the money market is in equilibrium.

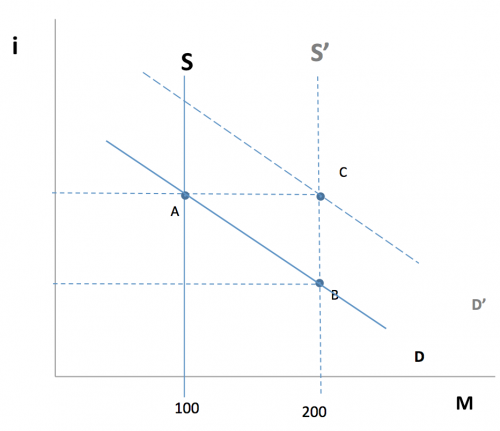

In my view the term “shortage” should apply to a situation where it is actually difficult to get money. I’ve read that there were shortages of money in Colonial America, due to British policies prohibiting the import of coin, combined with America using British pounds as the MOA. I recall a shortage of coins in 1964-65, when silver prices rose above the face value of quarters and dimes. But that’s not what happens in most recessions. People don’t say “I have plenty of wealth, I can afford that new BMW, but I just can’t find any MOE so I won’t buy it. They don’t buy the new BMW because they are poorer during recessions. Now let me be clear that they are poorer because the MOA (which is of course also the MOE in modern America) has either fallen in supply or risen in demand, depressing NGDP and throwing millions of people out of work (due to sticky wages.) So recessions are monetary problems in the sense of being caused by MOA shocks, but they don’t reflect a situation where people with plenty of wealth and a desire to buy just can’t find a way to convert stocks and bonds into cash and checking balances. So that raises the question of why there is no money shortage at point B. It sure looks like a disequilibrium point. The answer is that the opportunity cost of holding the MOA falls when the money supply doubles, as you can see in the famous “liquidity effect” graph below:

At point B the increased money supply has depressed interest rates. On the first graph this would show up as a shift in the demand for money. I didn’t draw the new demand curve on the first graph, but it would go right through point B (on the graph with 1/P on the vertical axis.) The money market is now in equilibrium. Even at point B when you take your paycheck to the bank to get some MOE to spend, the teller doesn’t say “sorry we are out of vault cash,” he hands over some MOE, whenever you need it. But there is also clearly a sense in which we are not in equilibrium in a broader macroeconomic sense. At point B the prices of all sorts of assets have changed (stocks, bonds, commodities, forex, perhaps even commercial RE), and this changes lots of relative prices since goods prices are sticky. In addition, at point B the expected rate of NGDP growth has risen sharply. In the short run these forces will push output above the natural rate, although in the long run the only effect will be a doubling of the price level.

The deeper question is whether the disagreement between myself and other MMs reflects something important, or do we agree as to what is going on, but simply characterize it differently.

That which has no practical implications, has no theoretical implications. I had originally assumed that my thought experiment with Z$s as MOE, but gold as the MOA, showed the practical advantage of my approach. But Nick’s comment convinced me otherwise. He saw the same set of facts as I did, but was able to interpret the hypothesized recession by using a “change in the real quantity of MOE” framework.

So right now I’m stuck. I can’t think of any experiment, no matter how far-fetched, that would resolve our dispute. If I’m not able to think of one, then I’ll end up filing this issue away as being unimportant. That is, I’ll assume we actually do agree, but we describe the exact same situation using different language (i.e. ‘equilibrium’ vs. ‘disequilibrium.’) In order to be convinced that there is a meaningful difference here I need to see a thought experiment that would produce different results from a MOA perspective as compared to a MOE perspective. Perhaps removing the MOE entirely would do that. But I’m not convinced. Does removing the MOE shows that the MOE is important, or that there is no such thing as sticky wages/monopolistic competition under barter?

PS. Saturos recently said this in response to an earlier post:

Scott, I’ll restate what I said. Of course employers can always liquidate their assets to pay wages. That’s not what I meant.

I want you to visualize the circular flow of income. When I say money, I mean an inflow of money. I mean money income.

Then we are in agreement, because I also think money income (NGDP) is the key. But it has to be money income measured in MOA terms, not money income measured in MOE terms.

Tags:

3. November 2012 at 07:34

” If I’m not able to think of one, then I’ll end up filing this issue away as being unimportant”

That was my position all along, I never saw a practical difference between these approaches.

I’m also going to suggest a thought experiment. Suppose both MoA and MoE are both fiat, with two separate agencies responsible for each, say Ministry of Units, and a Bureau of Payments. Which agency is more important? Which has the potential of cause more damage to the economy assuming another agency reacts optimally?

3. November 2012 at 07:57

123, If the MOA was fiat, but not the MOE, why would it have any value?

3. November 2012 at 08:18

I will study this more, but here is my current impression:

First, don’t assume the MOA is something where flow supply and demand is unimportant, and can imagine the stock falls in half.

Second, stop treating currency has the sole medium of exchange.

In recessions, the problem isn’t that people can’t go to the bank and get hand-to-hand currency from their accounts. There is no shortage of currency.

Currency is just one small part of the medium of exchange.

It plausibly is the only part that serves as medium of account under current conditions.

Second, the way the recession gets started is a shortage of the medium of exchange. People decide they want to hold more, and so they spend less. Now, once nominal income falls, the demand to hold the medium of exchange falls. That is how it clears up. There is a shortage at the equilibrium level of real income and output.

If you assume that all final goods prices are perfectly flexible, and only wages are sticky, then you can characterize the problem as real wages being to high, the quantity of labor demanded being too low (and the quantity of labor supplied maybe too high.)

But this is the wrong way to think about it. The problem is that prices and wages are too high relative to the quantity of the medium of exchange.

The problem can be fixed by increasing the quantity of the medium of exchange. Period.

Now, if you have some other medium of account, and the higher medium of exchange would raise the demand for it, creating a shortage at the defined price, then there would be a problem.

For the medium of account to clear at the defined price, other prices must fall, and so creating a sufficient quantity of the medium of exchange won’t work.

Again, it all becomes clearly if you stop imagining that the medium of account is something that is another type of money.

It will also help if you stop thinking of the medium of exchange as being currency.

Steel is the medium of account. Inventories of steel don’t exist. Checkable deposits are the medium of exchange.

Think about this scenario.

Stop treating hte medium of account like money. Stop treating the medium of exchange like currency.

3. November 2012 at 08:40

Lots of thoughts, hopefully this will make some sense.

At the micro level, MOA pricing in services tends to happen as equilibrium “question marks”. Or, when a service good is priced, a couple of things can happen. In healthcare the price tends to be adjusted to existing MOE at the end of pay periods. Whereas in other service offerings pricing and financing mechanisms are created to rely on tremendous variations in income. IOW equilibrium doesn’t get the simple pricing mechanism of production activity where participants have income levels that more readily correspond.

Also in macro terms any nation’s overall consumption basket is a direct reflection of both primary commodities and varying degrees of production processes. Here, NGDP also depends on – for instance – the different grades of oil that are currently primary in production. As some countries use up the oil that’s easier to get to, other countries become “ascendent” as their harder to reach oil becomes a bigger part of the marketplace. But what is important here in terms of equilibrium is, what kind of service basket is possible in realistic terms? When no one really knows and the question remains unanswered too long, knowledge is not able to fully augment production wealth. So Scott that is my argument for staying with this line of thought in monetary terms. I continue to plod ahead with what happens for value in use economies once NGDP draws that clear line with the full understanding as to why MOA is paramount.

3. November 2012 at 09:36

“If the MOA was fiat, but not the MOE, why would it have any value?”

Or suppose that MoA authority could redefine the MoA periodically however it wishes.

3. November 2012 at 10:10

Frankly, I’m just pleased that there’s a post on TheMoneyIllusion.com with my name in the title.

3. November 2012 at 11:26

OK, I’m done typing, get ready for some long replies…

3. November 2012 at 11:26

I think Bill’s criticisms in the above comment are correct, but I also think that there are more fundamental ones.

A minor quibble first though (actually not so minor): Nick and I would say that there is no “money market”. When money is the MoE, all markets are money markets. Your diagrams show the equilibrium in the demand and supply for holding stocks of nominal money balances aggregated through the inventories of all agents in the economy, not the flows which actually appear in exchange on each of the markets.

People don’t say “I have plenty of wealth, I can afford that new BMW, but I just can’t find any MOE so I won’t buy it.”

No, what they would say (if they were knowledgeable enough) is, “I have plenty of productive capacity, but due to the lack of MoE flow, I can’t exchange my production with that of others. The instrument for resolving the double coincidence of wants is absent; so I am effectively poorer, even though I can still work as hard and as well as I used to, and my employer is just as capable of facilitating my work as it used to be, and the problems of real economic calculation and recalculation are otherwise no harder than they used to be. Yes, I could incrementally restore the MoE flow by spending some of my engorged money balances; but why should I? The benefits of that, holding everyone else’s actions constant, would mostly go to everybody else.”

The reason why people’s wealth is lower is because their real incomes are lower, and their expected future real incomes. And that is because their ability to realize income from productive capacity depends on the medium of exchange, whose flow has dried up. (And it is that flow M*V, which of course always equals P * Y, which I think of as being the real “NGDP”).

Which brings me to my critique of your analysis in the post.

First of all I don’t know why you wouldn’t simply combine the two diagrams, like the rest of us do, and have “i” on the vertical axis and “M/P” on the horizontal. Anyway. Your analysis is an analysis purely of stocks, not flows. Indeed such an analysis is strictly incoherent, as there is no analysis of how the stocks get there, and how they change; no explanation of the process of moving from one equilibrium to another. Of course market monetarists do have such an analysis: it is called the “excess money-balances mechanism”, which is about flows just as much as it is about stocks.

All the points which you identify as representing equilibrium in stocks: so do I. My concept of disequilibrium in stocks is the same as yours. However – I disagree about the sequence of equilibria.

When there is an excess of money-balances (stocks), there is briefly a disequilibrium at the current level of nominal income. I agree that the first thing to adjust is nominal interest rates. This takes us into a temporary point of equilibrium at the same nominal income, but a lower interest rate, which you label “B”.

But this equilibrium is very short-lived. This is where I disagree with Keynesians too – the liquidity-effect of lower interest rates cannot possibly be responsible for all the increase in spending which occurs during monetary expansion, as the lower equilibrium interest-rate is the result of a fragile equilibrium in flows (in the bond market). The increase in flows of money for bonds must cease as soon as equilibrium in monetary stocks is acheived. At that point, the excess-cash balances mechanism takes over – the “hot potato-effect” proper. Not mere “portfolio rebalancing” which only occurs in the bond market, and perhaps some others; I am talking about a hot potato which spills over into every market, increasing the flow of money/MoE balances received into the inventory of stocks which everyone holds. I am talking about increased MoE flows on real assets and real goods and services of all kings, increasing the flow of MoE income for all sellers and workers, pushing up real Y.

Eventually, once real income has risen high enough, the hot-potato ceases. Because real income is higher, people are willing to hold a greater stock of real money balances, even at the previous natural interest rate. And they do; until prices eventually adjust upwards. Now the stock of real balances is lower; but also the flow of MoE immediately loses its purchasing power, and thus the real value of income and the demand for holding money stocks falls very rapidly to equilibrium. The final position is one of higher nominal money balances, the same real money balances, the same interest rates, and a higher price level (a lower real value of money). And the same process would work in reverse if there were a decline in money balances.

So your problem is that you ignore the actual booms and busts, the changing value of the Y variable as a determinant of the demand to hold money and its role of setting equilibria in money stocks. You rushed your analysis of money-balances, completely missing the most important equilibrium stage: the one where real income adjusts to bring demand and supply for money-balances into equilibrium. Call this point “gamma” (as it lies between “B” and “C”). At this point gamma, there is equilibrium in money balances, as real income has adjusted by enough to allow the demand to hold money to equal the available stock. But there is a disequilibrium in monetary flows. Indeed, as you saw from my description of the excess cash-balances mechanism, it is precisely this change in flows which is required to make the equilibrium in stocks adjust to the new level! And since prices are sticky, as nominal income adjusted in the face of the HPE, the variable that adjusted was not prices, but real income.

And how did real income adjust? Well, when the flow of money rose/dropped, instead of being absorbed by a change in prices there was a mismatch between the amount of real output people wanted to sell at the stuck price level and the size of the flow of nominal money-balances available to buy them. So a lot of stuff goes unsold, Keynesian-style, and gets put in inventory. So the “Keynesian cross” process begins to operate. And real income from selling goods moves up/down to the new equilibrium. At which point the “multiplier” ceased, as there was equilibrium between the stock of money and the demand to hold it. So at “gamma”, there is equilibrium in monetary stocks – but disequilibrium between monetary flows on the one side and the stuff waiting to be exchanged for monetary flows on the other. This is the recession (or boom).

And this is pretty much the analysis that Bill and Nick have been blogging about ad nauseam as well.

3. November 2012 at 11:27

That which has no practical implications, has no theoretical implications.

A lot of mathematicians would disagree with that.

Fortunately, our disagreement does have practical implications. (In theory.) The “experiment”, or litmus test, is in fact very easy. I suspect that perhaps you will never make it through all the comments I left on previous posts (which I still regard as having answered all points in this debate), but I had presented two cases. One is an economy with MoA but no MoE. And the other is an economy with MoE but no MoA. I claim that the former has no “demand-side recessions”; and I claim that the latter does.

Of course I remember previously that when I started talking about a barter economy with no MoE, precisely to give you the decisive thought experiment you now want: the one time you responded you responded by saying that barter was irrelevant…

Does removing the MOE shows that the MOE is important, or that there is no such thing as sticky wages/monopolistic competition under barter?

The former.

That was actually not correct. I gave in to clarify my answer to your objections, but in fact, since money intermediates nearly all exchanges, a lack of money flow impairs all exchanges. So the same thing preventing firms from earning new income to pay wages, would also hamper their ability to pay wages by liquidating assets, and even to get credit. All forms of money-intermediated exchange become more difficult. (And that is a testable prediction.) Hence financial markets, as well as real goods markets, suffer liquidity crises during a recession (except to the extent that financial markets can get by with different MoE than real goods markets, and those other MoE are less scarce in flow).

In fact that is probably the best way of putting it: “Recessions are always and everywhere a crisis of liquidity”.

Then we are in agreement

Unfortunately we are still not in agreement. Because despite quoting me thus, of all the pretty diagrams you posted above, none was the circular flow of income! You still insist on talking about stocks, not flows. I could immediately show you where you were going wrong on that chart.

But it has to be money income measured in MOA terms, not money income measured in MOE terms.

Yes – if the exchange rate between MoE and goods-in-general is fixed in MoA terms. But you don’t actually think that money income is the key, not the way we do. For you “money income” is interchangeable with “nominal income”. But for Nick, Bill and I, “money income” literally means a flow of money, of the medium of exchange. (Like on that circular flow of income chart.)

3. November 2012 at 12:40

STILL an absolute moratorium on any analysis of WHY prices are sticky, e.g. psychological effects of inflation, etc.

3. November 2012 at 13:49

MF – you might want to check out the other post that I inspired: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=16594

3. November 2012 at 13:56

“because the MOA (which is of course also the MOE in modern America)”

Getting somewhere? I assume that means no gold standard. Now can you be convinced that MOA and MOE are currency plus demand deposits?

3. November 2012 at 14:04

“In the short run wages and prices are sticky, so this shows up as less real output.”

What if they were not? Isn’t the debt still sticky?

3. November 2012 at 14:39

Question about money supply and interest rates: Interest parity tells us that the forward rate F is related to the spot rate S by the equation F=S(1+Rd)/(1+Rf) for a domestic interest rate Rd and foreign interest rate Rf. Violations of parity lead to arbitrage opportunities. Let the domestic currency be dollars and the foreign currency be gold. If S=$100/oz, Rd=2%, and Rf=1%, then F=$101/oz. Now, if the Fed increases the money supply, you monetarists say that Rd will fall to maybe 1%. This means F falls to $100/oz. The dollar is more valuable relative to gold, but of course monetarists say that the dollar should be less valuable. How do you guys reconcile that?

3. November 2012 at 15:25

bill woolsey: said “Second, stop treating currency has the sole medium of exchange.”

If “has” becomes “as”, I agree.

“In recessions, the problem isn’t that people can’t go to the bank and get hand-to-hand currency from their accounts. There is no shortage of currency.”

Agreed.

“Currency is just one small part of the medium of exchange.”

Agreed. Another part I am thinking of is demand deposits.

3. November 2012 at 15:26

This is but a thought experiment but I feel I need to try. Imagine MOE as a racetrack in which each measured foot of track is the money supply. While people may know collectively how many feet of track exist, that does not affect their rationale as individual players. Which means that individual players set up hurdles along the track that in turn need to be monetarily cleared, so that the total measurement of hurdles and track would become the MOA. However the entire apparatus may get measured as though the flat track is all that exists and the money supply is unchanged. If the measurement of hurdles is the same as track length (the supply of gold falls in half) who gets to the finish line?

3. November 2012 at 16:37

“Second, the way the recession gets started is a shortage of the medium of exchange.”

Probably.

“People decide they want to hold more, and so they spend less.”

I believe the amount of MOE falls first or the amount of MOE in circulation falls first.

“Now, once nominal income falls, the demand to hold the medium of exchange falls. That is how it clears up. There is a shortage at the equilibrium level of real income and output.”

Something similar that relates MOE to time.

“If you assume that all final goods prices are perfectly flexible, and only wages are sticky, then you can characterize the problem as real wages being to high, the quantity of labor demanded being too low (and the quantity of labor supplied maybe too high.)

But this is the wrong way to think about it. The problem is that prices and wages are too high relative to the quantity of the medium of exchange.

The problem can be fixed by increasing the quantity of the medium of exchange. Period.”

Yes! Yes! And, yes! But, how more MOE is created and its distribution matters!!!

3. November 2012 at 17:00

In order to be convinced that there is a meaningful difference here I need to see a thought experiment that would produce different results from a MOA perspective as compared to a MOE perspective. Perhaps removing the MOE entirely would do that. But I’m not convinced. Does removing the MOE shows that the MOE is important, or that there is no such thing as sticky wages/monopolistic competition under barter?

I also think money income (NGDP) is the key. But it has to be money income measured in MOA terms, not money income measured in MOE terms.

THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS MoA INDEPENDENT OF MoE

Your original hypothetical example of gold being a MoA, and Z$s being a MoE, is an example in which the market price of gold, in Z$s, IS a manifestation of MoE. Gold carries a price in Z$s by way of gold and Z$s being exchanged.

Prices on balance sheets, in either gold or Z$, is a function of exchanges. There can be no price of gold in Z$ unless gold is exchanged for Z$. There can be no price of Z$ in gold unless Z$ is exchanged for gold.

As soon as you are talking about prices, you are talking about exchanges. As soon as you are talking about exchanges, you are not independent of MoE!

The reason you can’t think of a thought experiment that would lead to different outcomes depending on whether you take an MoE perspective or an MoA perspective, is because MoA is derived from MoE. It’s not that money is useful as both a means of account and means of exchange, as if these two concepts are divorced and independent from one another. It’s that money as a MoE has enabled it to then be used as a MoA.

People account for the prices of things by way of exchanges of those things as against the commodity being accounted for. There is no sense in which a commodity is being used as MoA, divorced from that commodity being exchanged. The very accounting values themselves are the market PRICES of those commodities, and prices are manifested in exchanges.

3. November 2012 at 17:14

Bill

Second, the way the recession gets started is a shortage of the medium of exchange. People decide they want to hold more, and so they spend less.

This is incomplete. Recessions don’t start with a shortage of money. Recessions have to at least start with what causes the sudden “shortage of money”, and why the existing supply of money and existing supply of money growth is no longer sufficient.

3. November 2012 at 17:28

Mike

“Now, if the Fed increases the money supply, you monetarists say that Rd will fall to maybe 1%. This means F falls to $100/oz”

No, S rises to $101/oz. The dollar is indeed less valuable. However it is not expected to fall any further.

3. November 2012 at 19:56

M_F,

1) How can the amount of MOE in circulation go down?

2) an increase in the amount of goods/services (and/or an increase in financial assets)

3. November 2012 at 22:04

As soon as you are talking about prices, you are talking about exchanges. As soon as you are talking about exchanges, you are not independent of MoE!

MF, your first sentence is absolutely correct, I wish Scott would understand that. But your second sentence is wrong. Counterexample: every barter economy ever.

3. November 2012 at 22:28

“This is the recession (or boom)”

Oops! That’s wrong too. There is no disequilibrium in flows for a boom, as the quantity of output rises to meet the volume of flows (and if it doesn’t then prices adjust – we don’t see commodity shortages during booms, except maybe a few bottlenecks).

The disequilibrium in flows occurs only during a recession. Here the flow of newly produced output at its natural rate is too great for the shrunken flow of MoE. So the quantity of output actually sold falls below the natural rate. The difference is what we refer to as the general glut.

3. November 2012 at 22:28

Damn it. Well at least I didn’t italicize the whole page this time.

4. November 2012 at 00:22

Fed Up:

1) How can the amount of MOE in circulation go down?

If you mean money supply, money created via bank credit expansion can literally be erased from existence by being defaulted on or by being paid back.

2) an increase in the amount of goods/services (and/or an increase in financial assets)

If you are answering your own question, then this is an incorrect answer. More goods and services does not lead to less money in existence or in circulation. More goods and services will, ceteris paribus, lead to falling prices and unchanged nominal spending and money supply.

Saturos:

“As soon as you are talking about prices, you are talking about exchanges. As soon as you are talking about exchanges, you are not independent of MoE!”

MF, your first sentence is absolutely correct, I wish Scott would understand that. But your second sentence is wrong. Counterexample: every barter economy ever.

The context in which I made these arguments was a monetary economy. I meant exchanges of Z$s for gold, or vice versa. The preceding two paragraphs, I thought, set that context.

But by itself, you’re right, I agree, that second sentence would have been wrong.

4. November 2012 at 01:02

MF, monetary economies can have barter exchanges. But yes, the conceit of the scenario is that gold is only directly traded for Z$.

4. November 2012 at 01:45

MF, monetary economies can have barter exchanges. But yes, the conceit of the scenario is that gold is only directly traded for Z$

Monetary economies have MoE, so instances of barter are rather tangential to the argument I’m making.

Related to your point about the conceit of the example: If gold is only directly traded for Z$, then both the gold price of Z$ and the Z$ of gold (same thing) are each derived from exchange, and hence neither can be divorced from MoE.

In order to know what gold price is to be accounted for in the hypothetical MoA example, gold has be exchanged against Z$, which makes the alleged MoA example really a MoE example.

4. November 2012 at 01:47

If you take away Z$, and think about what would happen to the gold MoA, then the only way to account for the gold prices of all goods would be if gold were actually traded against all goods, and what does that imply? Yup, gold would be a MoE.

4. November 2012 at 01:50

You may already understand this, but it bears emphasis:

Accounting for prices in the MoA sense is derived from, it is logically a posteriori to, exchanges of that which carries a price, and in a monetary economy, we account for the money price of goods exchanged, i.e. MoE.

4. November 2012 at 05:26

If you take away Z$, and think about what would happen to the gold MoA, then the only way to account for the gold prices of all goods would be if gold were actually traded against all goods, and what does that imply? Yup, gold would be a MoE.

Not at all, there simply has to be a reachability relation from gold to every other commodity in the economy via exchange. We can use any arbitrary commodity in a barter economy as the numeraire, and then calculate implicity exchange rates with everything else. Only if gold was directly exchanged with everything else would it be a MoE, but for MoA purposes direct exchange is unnecessary.

4. November 2012 at 05:30

Does anyone here think MOA is “special”? It is the direct result of herd mentalities which are nonetheless individuals acting alone! As long as there is freedom, there are going to be people who think freedom is about cancelling interior flexibilities that would make it easier for all economic actors to freely participate. Nobody should kid themselves about this being brought about by the big bad government. It is also brought about by the wife of the conservative next door(and even the liberal down the street) who want to make sure every house sold on the market adheres to a certain size dimension and make to keep the riff raff out of town. Riff raff weren’t always this threatening but now the process of clearing the hurdles requires that everyone have a middle class income when many employees can only logically pay helpers a lower to middle class income. Yes government and finance get rich by setting up the hurdles and then everyone is stuck trying to pay for the grand display such as what happened in Stockton California. Blaming government is silly when each us us wants to raise the bar for our own benefit and consequently use government to do so.

What would the measurement of NGDP do in this instance? For one thing it would point out the absurdity of everyone trying to maximize wealth by insisting that everyone live like kings on an everyday budget.

4. November 2012 at 05:33

Correction: employees should be “employers”.

4. November 2012 at 06:04

Bill, I would agree with almost all of your analysis if you simply replaced “MOE” with”MOA.”

Saturos, You said;

“But this equilibrium is very short-lived. This is where I disagree with Keynesians too – the liquidity-effect of lower interest rates cannot possibly be responsible for all the increase in spending which occurs during monetary expansion, as the lower equilibrium interest-rate is the result of a fragile equilibrium in flows (in the bond market). The increase in flows of money for bonds must cease as soon as equilibrium in monetary stocks is acheived. At that point, the excess-cash balances mechanism takes over – the “hot potato-effect” proper. Not mere “portfolio rebalancing” which only occurs in the bond market, and perhaps some others; I am talking about a hot potato which spills over into every market, increasing the flow of money/MoE balances received into the inventory of stocks which everyone holds. I am talking about increased MoE flows on real assets and real goods and services of all kings, increasing the flow of MoE income for all sellers and workers, pushing up real Y.”

But that is also my view. The liquidity effect is an epiphenomenon. Given that I explicitly rejected this Keynesian view in the paragraph after my second graph, I’m puzzled as to why you would attribute this view to me.

At point B the money market is in equilibrium (in stock terms, which is the appropriate way to define equilibrium for an asset like money.) But the macroeconomy is not in equilibrium. The macroeconomy (NGDP) is in the process of transitioning toward a higher level of NGDP. The factors causing that transition are explained in my post, all sorts of asset prices change, and also expectations of future NGDP will increase. This causes the current flow of money expenditure (aka NGDP) to rise.

You keep insisting that the stock of money is the wrong way to define money, that we should look at the flows of money expenditures. I disagree, I think the stock of money is the right way to define money (it is certainly the traditional monetarist way of defining money.) I believe that we already have a perfectly good term for the flow of money—NGDP. So yes, if you insist on equating the MOE and NGDP, then I can’t argue against the proposition that more NGDP is caused by changes in the MOE. But that doesn’t tell me what caused that flow of expenditure to increase. In fact, the increase was caused by changes in the market for the MOA. Then the MOE/NGDP adjusts to a new equilibrium, based on those MOA market shocks.

You said;

“No, what they would say (if they were knowledgeable enough) is, “I have plenty of productive capacity, but due to the lack of MoE flow, I can’t exchange my production with that of others. The instrument for resolving the double coincidence of wants is absent;”

I believe there is plenty of MOE, but rather the shortage of MOA causes NGDP to fall to a level where at existing sticky wage levels it is not PROFITABLE to produce more tonnes of steel. But if you insist on producing and selling them at a loss, you will have no trouble finding buyers. MOE is not the problem.

You said;

So your problem is that you ignore the actual booms and busts, the changing value of the Y variable as a determinant of the demand to hold money and its role of setting equilibria in money stocks. You rushed your analysis of money-balances, completely missing the most important equilibrium stage: the one where real income adjusts to bring demand and supply for money-balances into equilibrium. Call this point “gamma” (as it lies between “B” and “C”). At this point gamma, there is equilibrium in money balances, as real income has adjusted by enough to allow the demand to hold money to equal the available stock. But there is a disequilibrium in monetary flows. Indeed, as you saw from my description of the excess cash-balances mechanism, it is precisely this change in flows which is required to make the equilibrium in stocks adjust to the new level! And since prices are sticky, as nominal income adjusted in the face of the HPE, the variable that adjusted was not prices, but real income.”

It’s amazing how similar we see the picture, but how different the labels we attach. I agree that gamma is the key. Indeed I agree with almost your entire post–except that I believe the HPE works for the MOA, not the MOE, and what you call MOE/money flows/M*V, I call NGDP/P*Y. I don’t see those changes in money flows as the cause of monetary policy shocks, but as the EFFECT of changes in the market for the MOA.

4. November 2012 at 06:15

Saturos, In your next post you ask about a scenario where there is an MOA but no MOE. In that case the MOA cannot be sold for MOE, it must be sold for other goods. To avoid having the MOA become the MOE, assume only 5% of all transactions involve gold, but everything’s still priced in gold terms.

Now consider a case where gold is the MOA. A new car costs one pound of gold. Suddenly gold nuggets fall from the sky like manna from heaven. Obviously gold becomes much less valuable. But autoworker wages are sticky in gold terms. So the price of cars become an incredible bargain, and car sales soar until auto wages have adjusted.

QED.

Mike, Isn’t this just the Dornbusch overshooting model? If you increase the money supply by X%, the forward rate goes to whatever the equlibrium forward rate is according to the quantity theory of money (presumably X% higher), and the spot rate goes to the level that makes the interest parity condition hold. Maybe I misunderstood your question . . .

4. November 2012 at 06:33

Net Worth is a more important part of a micro-decision maker (real people) than that person’s annual or monthly income, with lifetime expected Net Worth being even more important.

Net Worth is the stored Medium of Exchange (stored as Medium of Account).

Net Worth is highly market dependent, when most of most people’s net worth is the market value of house minus their outstanding mortgage; net home equity.

When house prices dropped, net worth dropped, so Medium of Exchange dropped. Or was that Medium of Account? Or both?

Trying to make an exclusive argument of where net worth fits into a monetary theory of Mediums of exchange or account seems like physicists arguing about light as wave or particle — it’s both.

Deal with it.

What are the different policy implications? What policies are one the table, what will be their effects.

Big stimulus “failed”, but would NGDP targeting, after the house bubble pop of 2006, really have done much better?

And, what is the mechanism of increasing or decreasing the “supply” of money?

(For me, more tax cuts or better, tax loans, to increase supply. Of MoE or MoA.)

4. November 2012 at 06:34

According to your two diagrams, which are indistinguishable except for the variable employed on the vertical axis, one is left to conclude that (1/P) = i. Thus, contrary to all of your previous writings, you now apparently believe that expansionary monetary policy will lead to a reduction in interest rates. In short you cannot have things both ways.

1) If you use the first diagram (which is consistent with 99.9% of everything you’ve written) and combine its implications with the Fisher relation, expansionary open market operations lead to INCREASES in nominal interest rates through their effects on expected future inflation.

2) With regard to any notion of a “liquidity effect,” please see a paper by Laidler from the late 1960s or Ireland’s 2005 paper in IER. Both point out that a rose is not a rose is not a rose. Do we mean an effect of open market operations on the fed funds rate? The interest insensitivity of the demand for money to a LONG-term rate of interest (the original definition) or about three other possible definitions? But combining your second figure with the first has been the cause of more confusion than almost anything I can think of, including (e.g.) the Fed’s completely misguided policy actions of the late 1970s where continued attempts to push interest down with more expansionary money growth only backfired with ever-higher nominal rates.

4. November 2012 at 08:20

Gold nuggets fall frorm the sky. No one shows up at the gold shops to buy gold.

Why do they raise the prices of the other goods?

You consistently assume a Walrasian Auctioneer.

4. November 2012 at 08:32

Monetary disequilibrium exists when the quantity of the medium of exchange is different from the amount that would be demanded if the interest rate equals the natural interest rate and real income equals potential income.

Monetary disequilibrium does not involve empty money shops nor does it involve those operating money shops having full shelves of moeny and few customers showing up.

Because money is the medium of exchange, people will take it even if they don’t want to hold it, and people can accumulate it by simply spending less.

I don’t agree with Saturos (and Rowe, I think) regarding the identification of money with the flow of money expenditures.

A shortage of money does result in reduced money expenditures, but the demand for money isn’t the flow supply of goods (or the desire to earn money incomes.)

The shortage of money exists because if those people who want to work, produce, and sell actually did, they _would_ want to hold money balances (mostly they would want to earn and spend, but they would also want to hold money balances) and this would reslt in a demand for money greater than the quantity.

The quantity of money is less than what the demand would be at potential output and the natural interest rate.

In a system where money is not the medium of account, then the way changes in the supply or demand for the medium of account results in changes in the price level is through changes in the quantity of money or the demand to hold money.

And, if there is some change in the quantity of money or the demand to hold money that would cause a change in the price level, there must be some institution that causes the quantity of money (or perhaps the yield on money) to adjust so that the market for the medium of account clears at its defined price.

Anyway, money is still the medium of exchange.

Also, your wage fixation is an error. What if wages are perfectdly flexible and final goods prices are perfectly fixed?

Does that solve the problem?

4. November 2012 at 09:18

“I can’t think of any experiment, no matter how far-fetched, that would resolve our dispute.”

I like your Zimbabwe example with different MOA and MOE, where MOA prices are the sticker prices in shop aisles and MOE prices are at the shopkeeper’s till. Assume that one set of shops sells a certain unique and vital item. These shops can’t easily adjust their till price ie. till prices for type-1 shops are rigid in the short term. (The till price is Zim$/oz.) The other type of shop sells totally different stuff and can immediately adjust their till price.

My guess is that if you have a huge increase in demand for Zim$ you could have a recession because type-1 stores can’t reduce their till price enough to keep people from withholding purchases, and only type-1 stores stock this vital good.

It seems to me that MOE and MOA is not always the key distinction in determining what causes a recession. It also depends on whichever set of prices you make sticky – MOE prices at the till or MOA sticker prices in the aisles or both, and also the nature of Zimbabwean shops (can you substitute from one shop to the other?).

4. November 2012 at 11:19

Scott, you said:

Given that I explicitly rejected this Keynesian view in the paragraph after my second graph, I’m puzzled as to why you would attribute this view to me.

Because in your original post you completely forgot to look at the equilibrium where prices and interest-rates were the same, and only real income had adjusted to hold the new money stock!

In fact, the increase was caused by changes in the market for the MOA.

Ain’t necessarily so. An increase in the velocity of/decrease in the demand for holding $Z, if the extra circulation did not spill over into higher Z$ prices of gold but only into the other markets, would change NGDP without changing the value of the MoA. Unlikely, but theoretically possible.

I believe there is plenty of MOE, but rather the shortage of MOA causes NGDP to fall to a level where at existing sticky wage levels it is not PROFITABLE to produce more tonnes of steel. But if you insist on producing and selling them at a loss, you will have no trouble finding buyers.

That’s wrong. Assume that wages and prices have adjusted downwards by the same percentage everywhere. (If wages and prices adjusted by different amounts, then we would be back to the too-high real wages problem; if they adjusted differently in different places it would be a relative price change not affecting all industries in the same way, the essence of a general glut.) So say that gold’s equlibrium value is 50% higher, but wages and prices adjust everywhere by falling only 25%. Why should the remainder show up as a change in output? Indeed, why should the remaining distance to equilibrium in the gold market make any production less profitable than it was, given that real relative prices are all still the same?

Indeed I agree with almost your entire post-except that I believe the HPE works for the MOA, not the MOE

That’s silly of you, since the HPE requires everyone to be holding inventories of an asset which they accept in exchange for other goods but which has no intrinsic value. That indicates MoE, not MoA. See here: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/09/all-money-is-helicopter-money.html

Scott, you promised we were going to ignore changes in the real wage! You are right that for booms, unlike busts, the mechanism you just gave is probably more relevant. But I want to talk about the case where: a) real wages are constant, and b) relative prices do not change across markets/industries. Try repeating your argument with those restrictions, and see if it can explain booms, let alone busts. You will see that the key is to explain fluctuations in quantity demanded at the same price level across all industries, which is not possible unless you consider the generalized market with all output Y on one side and the medium of exchange M on the other.

I will admit one thing , though: it’s clear that your own explanation for why booms occur crucially depends on relative prices changing, something which I missed the first time I read the post. But do you really think that booms are not possible without shifts in relative prices? And recessions most certainly are possible without such shifts; indeed the dominant mechanism requires no such shifts. Again, here is scope for empirical investigation; we can run tests similar to the standard ones for comparing Austrianism versus Keynesianism/Monetarism to see whether shifts in relative prices of real goods and assets are quantitatively significant in explaining recessions. (Spoiler alert: the tests don’t favor you.)

In conclusion, perhaps the root problem here is that you are suffering from an even more fundamental disorder: inadequate time spent reading Nick Rowe. Seriously, if he can’t wake you from your dogmatic slumbers no one can.

4. November 2012 at 11:20

…the demand for money isn’t the flow supply of goods (or the desire to earn money incomes.)

Bill, I’m distinguishing between the stock demand for money (which you are talking about) and the flow demand for money (and so does Nick, I think). It is in the latter sense that the economy is still in monetary disequilibrium even after real income has fallen. And it is this disequilibrium which puts downward pressure on prices to adjust and end the recession.

JP Koning, have you read Mankiw on this? Of course it’s the MoA prices on the stickers that are sticky. (Hence, “sticky prices”, geddit?)

4. November 2012 at 12:06

Scott: “In order to be convinced that there is a meaningful difference here I need to see a thought experiment that would produce different results from a MOA perspective as compared to a MOE perspective. Perhaps removing the MOE entirely would do that.”

Consider a simple economy. Haircuts, manicures, and massages are produced and traded. Each person produces one of the 3 goods and consumes the other 2 goods.

Gold is the MOA and MOE. Start in equilibrium, where (we assume) all 3 goods have the same price in terms of gold. One ounce of gold per job. Hold prices fixed, then halve the stock of gold. Every individual wants to sell more of one of the the three goods, and buy less of the other 2 goods. There’s an excess supply of all 3 other goods in terms of gold. There’s a recession. The quantity of trade shrinks until each wants to sell more of one of the 3 goods, but does not want to buy either more or less of the other 2 goods.

Now assume someone invents a new way for all 3 women to meet and do a 3-way barter deal. So gold is still the MOA but not the MOE. There is no MOE. “I cut you hair while you do her nails and she gives me a massage”. (Note that all 3 prices are still one ounce of gold). The recession ends immediately, even though there is now an excess demand for gold.

4. November 2012 at 12:11

In the above I (implicitly) assumed there was a demand for a stock of gold to wear as jewelry, and the jewelry demand was large relative to the monetary MOE demand for gold, so that when the resort to barter and the MOE demand for gold disappears, there is still an excess demand for gold as jewelry.

4. November 2012 at 12:15

There you go Scott. QED.

4. November 2012 at 12:17

Bill: “I don’t agree with Saturos (and Rowe, I think) regarding the identification of money with the flow of money expenditures.

A shortage of money does result in reduced money expenditures, but the demand for money isn’t the flow supply of goods (or the desire to earn money incomes.)”

I don’t think I disagree with you there. An initial excess demand for the stock of money *causes* an increased flow demand for money (people try (and fail) to sell a bigger flow of goods) and a reduced flow supply of money (people try (and succeed) to buy a smaller flow of goods). They also try (and fail) to sell part of their stocks of other assets.

4. November 2012 at 13:21

M_F’s post said:

“Fed Up:

1) How can the amount of MOE in circulation go down?

If you mean money supply, money created via bank credit expansion can literally be erased from existence by being defaulted on or by being paid back.”

I mean MOA = MOE = money supply = currency plus demand deposits, so OK for those two. I was also looking for saving, taxes, and trade deficit in addition.

“2) an increase in the amount of goods/services (and/or an increase in financial assets)

If you are answering your own question, then this is an incorrect answer. More goods and services does not lead to less money in existence or in circulation. More goods and services will, ceteris paribus, lead to falling prices and unchanged nominal spending and money supply.”

MOE stays the same, agreed. But, more goods/services means there is a shortage of MOE, more needs to be created. How more is created and how it is distributed matters.

4. November 2012 at 13:39

Demand and supply of the MOA only matter because all/many other prices are sticky in terms of the MOA.

Suppose government institutes rent controls, where the controlled rental is indexed to the CPI (or GDP deflator, or whatever). That means all/many prices are sticky (fixed) in terms of apartments. If rent controls are binding, that creates an excess demand for apartments. People would like to sell more other goods and buy less other goods, and use the proceeds to rent more apartments. But that does not create a recession. Because they know they cannot in fact rent more apartments. So they go on doing what they would have done anyway.

4. November 2012 at 13:49

Fed Up:

I mean MOA = MOE = money supply = currency plus demand deposits, so OK for those two. I was also looking for saving, taxes, and trade deficit in addition.

Saving does not lead to a reduction in money supply. Saving is merely using earnings for purposes other than consumption. Saving is not cash holding. All cash is held by someone at any given time.

Taxes also does not reduce the money supply. Taxation is money taken by the state. Since the state does not tax merely to hoard, but to spend, then it would be more accurate to connect taxation with government spending, and put those on two sides of the same coin, as it were, instead of keeping it separate from government spending,

4. November 2012 at 13:59

Nick Rowe:

To be accurate, what “people would have done anyway” is paid more for apartment rentals, but with the price controls, they cannot, so there is a “spill over” (nominal) demand for goods other than apartment rentals.

More importantly, your example of rent controls is not divorced from MoE. The price of the apartment rentals is a function of MoE. Saturos agrees that if you are talking about prices, then you are talking about exchanges, and if you are talking about exchanges, you are talking about MoE (in a monetary economy).

4. November 2012 at 14:09

Nick Rowe:

If these three services/goods each carry a price of 1 ounce of gold, then you are, whether you realize it or not, arguing that each of these services/goods are being exchanged for 1 punce of gold. If you insist that they are not bieng exchanged for gold, then you cannot presume that they each carry a price of 1 ounce of gold. Prices cannot be abstracted away from exchanges, for prices are themselves ratios of exchange.

We say a good carries a certain price in gold, or dollars, or whatever, because that good is being exchanged for gold, or dollars, or whatever.

4. November 2012 at 16:01

mb, One is left to conclude that i = 1/P? Is that a joke? If so, I missed the humor.

Bill, Wait a minute. Are you saying that if we were knee deep in gold that it would still sell for (the commodity equivilent of) $1700 an ounce. I’m not assuming a Walrasian auctioneer, just the obvious assumption that gold’s value would fall. I seriously wonder how that can even be disputed?

Saturos, You said;

“That’s wrong. Assume that wages and prices have adjusted downwards by the same percentage everywhere.”

First of all, it makes no sense to say “that’s wrong,” and then assume a completely different set of assumptions from what I assumed. Rather you should say “I don’t like your assumption that prices would fall more than wages.” If prices and wages and all costs fall at exactly the same rate in a prefectly competititive industry, then output doesn’t change at all. If you are assuming that gold’s value rose 50%, and that this reduced equilibrium NGDP, by an equal percentage (actually minus 33.3% if we are using ordinary percentages) then if wages and prices fell by 25% the rest of the decline would be in output.

You said;

“That’s silly of you, since the HPE requires everyone to be holding inventories of an asset which they accept in exchange for other goods but which has no intrinsic value.”

Not at all. If gold falls from the sky as I assumed, then in the ultra-short run (until interest rates adjust) people would be holding more gold than they wished to hold, at the current market value of gold. They’d try to get rid of this gold, and that would depress its value and drive up prices. That’s the hot potato effect. If all prices adjusted immediately, then (as with cash) people would gladly hold the larger gold balances, and there’s be no HPE. Of course in the real world short term interest rates would fall, and various asset prices would rise, as those prices are flexible.

Now I will admit that the gold price of currency would soar, and so you’d also get a HPE for currency, but the gold market shock would be what got the ball rolling. It would be the ultimate monetary shock, everything else is endogenous.

You said;

“You will see that the key is to explain fluctuations in quantity demanded at the same price level across all industries, which is not possible unless you consider the generalized market with all output Y on one side and the medium of exchange M on the other.”

I’m not really sure what you are doing here. Either you have perfect competition, or you don’t. If you have perfect comp, then if input and output prices fall equally, there will be no real effect. But if not, if there is a real effect, then you can’t assume that wages and prices fall at the same rate, and still talk about “quantity demanded” as if you have some sort of supply and demand model at work. S&D models only work in competitive industries, not monopolistic comp. If you have monopolistic comp, it’s perfectly ok to argue that an adverse nominal shock will reduce both prices and output, regardless of what caused the adverse nominal shock. Indeed if you assume monopolistic comp. with sticky prices, then any deflationary shock will reduce output in the short run.

But I’m not that interested in the output market. Output can move around for lots of reasons that have nothing to do with demand-side recessions. Employment shocks get much closer to the heart of what we mean by a recession—involuntary unemployment. That’s why I keep coming back to the ratio of hourly wages to NGDP. The ratio of wages to prices doesn’t matter, except in the relatively rare perfect comp industries. For monopolistic comp you look at W/NGDP. An adverse gold market shock reduces NGDP and raises unemployment. I think even Nick agrees with that, but he believes it occurs because the adverse MOA shock impacts the MOE stock measured in MOA terms.

You said;

“But do you really think that booms are not possible without shifts in relative prices?”

Suppose there was a huge flow of gold from heavan. Assuming the MOE price of gold was flexible, then the value of MOE in gold terms would soar. And you could use the HPE for MOE. So no, I don’t think relative price changes are necessary. Now assume even the MOE/MOA price is fixed. That implies no liquidity effect, and indeed no effect on asset prices like stocks, bonds, RE, commodities, etc. I suppose in that case the MOA must become a MOE, at least off the top of my head I can’t think of any other way to address the surplus of gold. People will try to spend the extra gold on goods directly. I still think it would create a boom, but I suppose one could argue that in that case the MOA has become a de facto MOE. If they could not spend gold, then it would no longer be the MOA. I’ve always assumed the MOA was traded in a free market and that the price of the MOA was the actual market price. Otrherwise how can it be the MOA?

More to come . . .

4. November 2012 at 16:25

Nick, I assumed the MOA market is in equilibrium. If it’s not in equilibrium, in what sense it is the MOA? When they do barter, in what sense are prices sticky in gold terms? BTW, the official price of gold in the US was $35 dollars an ounce in 1970 (under Bretton Woods) but the market price was higher. So although gold was de jure the medium of account, de facto it was not. There was a gold shortage. I’m claiming the MOA is the key variable if and only if it truly is the MOA. If and only if other prices truly are quoted in gold terms, at the going market rate for gold. In your example they are not, as the gold market doesn’t clear.

Just to be clear, I completely agree that barter would solve the problem. But that would be equally true if we didn’t abolish the MOE, but just sort of ignored it, didn’t use if very often. If 99.9% of transactions are done with barter and the MOE is mostly ignored, then there is no recession, even if you have a MOE. That seems parallel to me. In your example, 99.9% of the markets are in equilibrium, but the gold market is not. In both cases you are sort of sidelining one of the roles (MOE or MOA) and in each case you go to barter, and in each case there is no recession, because as soon as you go to barter, there is no longer a price stickiness problem. And that’s true regardless of whether there is a MOE, a MOA, both or neither.

Ditto for the apartment example. If apartments are the MOA, and are not in equilibrium, then I completely agree that my MOA model is worthless. The MOA must trade at an equilibrium price for this to matter.

But you are in great company. In the Monetary History F&S said FDR’s gold buying program of 1933 was no different from an agricultural price support program. They forgot that gold prices matter much more because it was expected that we would soon return to the gold standard at a new price, and gold would once again become the MOA.

4. November 2012 at 18:55

M_F’s post said:

“Saving does not lead to a reduction in money supply.”

But it does reduce the amount of MOE in circulation. If paying down debt is considered saving, then it could reduce the amount of MOE if it is used to pay back a bond owned by a bank or bank-like entity.

“Taxes also does not reduce the money supply.”

But it does reduce the amount of MOE in circulation, or it could reduce the amount of MOE if it is used to pay back a bond owned by a bank or bank-like entity. If the gov’t budget is balanced, the reduction and increase should cancel.

“Saving is merely using earnings for purposes other than consumption. Saving is not cash holding. All cash is held by someone at any given time.”

I save (not consume, not invest) in the MOE. I then decide what financial asset gives me the best return, including just holding the MOE.

4. November 2012 at 21:44

(actually minus 33.3% if we are using ordinary percentages)

Yes, sorry. My bad.

If prices and wages and all costs fall at exactly the same rate in a prefectly competititive industry, then output doesn’t change at all. If you are assuming that gold’s value rose 50%, and that this reduced equilibrium NGDP, by an equal percentage (actually minus 33.3% if we are using ordinary percentages) then if wages and prices fell by 25% the rest of the decline would be in output.

Scott, I can’t make any sense out of this. It seems like you are contradicting yourself. Let’s assume perfect competition here. (Is that OK with you?) We assume the equilibrium value of gold, in a barter economy with no MoE, rises 50%. We assume that NGDP or the price level now needs to fall by a third. Then in our example wages and prices both fell by only 25% (with no shift in relative prices). Will there be a recession, as in your second sentence? Or no recession, as in your first? (And in another sentence later on.)

As a prominent former Australian politician might put it, “PLEASE EXPLAIN”.

They’d try to get rid of this gold, and that would depress its value and drive up prices.

Scott, the HPE requires the hot potato to be passed back and forth between the same people, or around in a circle. Why would people keep accepting and reaccepting gold in exchange if it wasn’t MoE? If people bought the gold that others were ridding themselves of for intrinsic value, you couldn’t get it back to that person (or some other fungible bit of gold) by lowering the price. Why would I buy gold from you for $x worth of goods, and then sell it back to you for <$x worth of goods?

As Nick says, money is always and everywhere a hot potato. The hot potato effect never really ends. What does happen is that nominal income stops rising/falling, so that the flow of hot potatoes stops changing and the same flow keeps getting passed around under the stock-equilibrium condition at the same price. Which is necessary, in order for GDP to be sold to consumers.

But if not, if there is a real effect, then you can’t assume that wages and prices fall at the same rate, and still talk about “quantity demanded” as if you have some sort of supply and demand model at work.

Scott, surely you troll. There isn’t such a thing as “quantity demanded” under monopolistic competition? *puts on best Jerry Seinfeld voice* Really?

Why can’t we hold the levels of both prices and wages fixed under monopolistic competition? Or reduce them by the same percentage? Anyway it doesn’t matter, my fundamental argument has little to do with market structure. As Nick said you only need monopolistic competition to explain “pure demand-side” booms, not busts.

I believe we can have monopolistic competition under barter. Can you explain why it is you believe that a purely nominal shock would reduce output or employment under barter conditions, without any change in real wages or relative prices?

“But I’m not that interested in the output market… That’s why I keep coming back to the ratio of hourly wages to NGDP.”

For the last time, if NGDP means P*Y and not M*V, and if “the output market doesn’t really matter” – then it is meaningless to say that wages/NGDP “causes” anything. We are holding W/P constant, because WE AGREED THAT THAT WAS A SEPARATE FACTOR IN CAUSING RECESSIONS, which we are leaving to one side. Wages have stopped falling, and now unemployment is supposed to rise with W/NGDP. But you say Y is irrelevant. And P, from above, is now stuck. So what does further “falling NGDP” mean? Why, it means falling employment, of course. So I am back to arguing with Mr. Tautology. (It’s like that argument with MF never really ended.)

Now, we could alternately say that Y does matter. Then when P gets stuck, Y begins to fall, because the flow of MoE spending on Y has fallen, and Y needs to be sold for MoE to be consumable and counted in GDP. Now falling sales of Y cause less workers to be employed (or less labor hours hired) at the same real wage, a la Keynes. So with W and P fixed, falling NGDP means falling Y, which means falling hours worked.

4. November 2012 at 21:44

If they could not spend gold, then it would no longer be the MOA. I’ve always assumed the MOA was traded in a free market and that the price of the MOA was the actual market price. Otherwise how can it be the MOA?

???

Scott, I think you’ve just lost the argument here.

“Spending” is what we do with the MoE. It intermediates all exchanges. An MoA is just any asset or commodity used as the numeraire of the economy. It could be wheelbarrows of gold, or the wheelbarrows themselves. You don’t “spend” wheelbarrows, any more than anything gets “spent” in a barter economy without MoE. If I barter bread for chickens, neither bread nor chickens was “spent”.

Now you’ve just said to me, “If gold isn’t spent it isn’t MoA”. In other words, if the MoA isn’t an MoE, it isn’t an MoA.

What the heck?

Your second sentence is even worse. The whole point of my argument has been to show that, with MoA and no MoE, and no relative price shifts (including changes in the real wage), it is incoherent to speak of recessions whilst the MoA is trading at equilibrium price. Because the goods-price of MoA is the inverse of the price level, if a sticky price level prevents the output-market from clearing (and hence all workers from being employed at the same real wage), this logically implies that the MoA price, too, is stuck out of equilibrium. The whole point is that, unlike MoE, if the MoA price tries to rise to equilibrium because of excess demand, but the price level gets stuck halfway, the remaining excess demand CANNOT be resolved, as with MoE, by falling demand for MoA as a function of real income. Because there is no reason why real income should fall! People simply go on bartering at the same relative prices. (In fact the excess flow demand for MoE is never cleared, until the price level falls and the recession ends. The excess flow demand for MoE is the recession. Obviously it is, as why should any other kind of excess demand involve a recession?)

There’s no reason why the MoA should affect anything other than prices in this barter economy; the MoA, by assumption, is something irrelevant, like peanuts, used only to calculate common prices.

So now you want to say that being the MoA logically requires the price to always be in equilibrium? Even though the price level, which is the inverse of the price of MoA, is sticky? How’s that work? Is it impossible for this sticky price-level barter economy to have an MoA at all times, then?

I repeat, what the heck?

As I said earlier:

If the price of MoA gets stuck in disequilibrium, we can still use it as the MoA. Just calculate all output prices in terms of that disequilibrium price, just as we used the equilibrium price before. (That’s what Nick did in his examples.) Nothing about *accounting* for all prices in terms of one other price, says anything about whether that price has to be in equilibrium or not.

In any case, gold doesn’t have to be traded for the whole GDP basket to be the MoA. There could be a market where gold is bartered only for bananas in our barter economy, and bananas are part of the complicated web of exchanges that make up the rest of the economy. But gold is still the MoA, as we can calculate implicit prices in terms of gold for everything else. (Because, as I explained to MF, there is a reachability relation between gold and everything in GDP via exchange.) So a surplus or shortage of gold in the gold-bananas market need have no impact on the successful trade of everything else. In or out of equilibrium, gold has no value in facilitating exchange. Production, allocation and consumption of GDP does not depend on gold.

The only reason why this debate has lasted so long is that you keep evading the key challenge: How can there be pure demand-side recessions in a barter economy? I don’t mean shocks to productive capacity, I don’t mean changes in relative prices or real wages, I mean declines in the aggregate quantity of GDP demanded by economic agents. Assuming everyone still wants to earn as much (no mass vacations, another “real shock”), how does this happen? Why doesn’t Say’s Law hold? How does “demand create its own supply”?

4. November 2012 at 21:45

Your replies to Nick seem absurd. How can 99.9% of transactions be conducted by barter, and we still have a general medium of exchange? That’s just pure nonsense.

You don’t seem to understand Nick’s example. In the beginning, everything is bartered, and nothing is sidelined. The MoE is required to sell anything. Then when they switch to barter, by definition there is no more MoE. No “sidelining”, it is gone. Kaput. Now gold is only a MoA.

In reality, ignoring the MoE would mean a permanent collapse in output, as an economy like ours doesn’t work without MoE. As can be seen when the flow of MoE dries up relative to the price at which output can be traded for it, which we call a “recession”.

Honestly, how can you say this: “because as soon as you go to barter, there is no longer a price stickiness problem” without acknowledging that the relevant sticky price is really the price of output-in-general in terms of the MoE? And also the ratio of hourly wages to the MoE, as they are what causes output to be sticky? Indeed, even if output prices weren’t sticky, sticky nominal wages : nominal (MoA) value of the MoE would lead to recessions, as now there isn’t enough MoE income flow to pay all the workers, right? That’s what you mean by wages/NGDP, isn’t it? Except you are confused by the fact that prices are usually denominated in the medium of exchange. If they are not, then it is only the ratio of nominal wages to the nominal value of the flow of MoE (so if the MoE stock falls in nominal value, its flow velocity must increase) that can put people out of work, demand-side. There are no pure demand-side recessions without the MoE.

I think F&S were wrong, the gold-buying program was very different from an agricultural price-support. The gold buying program increased the flow of medium of exchange. Consequently people reduced their reliance on substiture scrip and barter, and output started to recover.

Scott, I realize that I am on a fool’s errand here. I am trying to accomplish the Sisyphean task of changing the mind of the man who has spent the past four years (nay, the past 25 years) as a holdout against the rest of the economics profession, peddling his own theory of the Great Recession, braving scorn and derision from the rest of the economics world. (And he was right about that.)

I don’t actually expect to win this debate. We haven’t seem to have made much progress thus far. I believe I understand your point of view (as far as it is possible, as there seem to be lapses of reasoning embedded in it) by now. You don’t seem to have grasped the thrust of the arguments I am making. That’s OK. Really I just want to know how far it is possible for reasoned debate to actually resolve issues seemingly amenable to reasonable resolution, on the internet. We’re both rational people. Aumann’s Theorem says we can’t agree to disagree. So if I understand what you think, and you understand what I think… it should be possible for us to reach a joint conclusion, even if one with uncertainty in it.

In theory.

4. November 2012 at 21:50

Whoops, that should have been “In the beginning, everything is traded using a medium of exchange, and nothing is sidelined.”

I can never finish on a strong note, can I?

5. November 2012 at 05:51

Saturos, You said:

“Scott, I can’t make any sense out of this. It seems like you are contradicting yourself. Let’s assume perfect competition here. (Is that OK with you?) We assume the equilibrium value of gold, in a barter economy with no MoE, rises 50%. We assume that NGDP or the price level now needs to fall by a third. Then in our example wages and prices both fell by only 25% (with no shift in relative prices). Will there be a recession, as in your second sentence? Or no recession, as in your first? (And in another sentence later on.)”

If the entire economy is perfectly competitive, then the price level is flexible. If wages are equally flexible then monetary shocks have no real effects. Pefectly competitive industries ar ealways i nequilibrium if their input prices are also perfectly competitive. My point was that you were trying to show than my MOA shocks would have no real effects, in a (unrealistic) scenario where MOE would also have no real effects. So you have no recessions either way.

You said;

“Scott, the HPE requires the hot potato to be passed back and forth between the same people, or around in a circle.”

I suppose you can define it that way, but my point is that the value of gold in my example falls for exactly the same reason that the value of cash falls in the HPE example. People initially have larger stocks then they wish to hold. They try to get rid of these excess stocks. In aggregate they cannot do so. Their attempt to do so gradually reduces the value of these stocks in the marketplace.

You said;

“”But if not, if there is a real effect, then you can’t assume that wages and prices fall at the same rate, and still talk about “quantity demanded” as if you have some sort of supply and demand model at work.”

Scott, surely you troll. There isn’t such a thing as “quantity demanded” under monopolistic competition? *puts on best Jerry Seinfeld voice* Really?”

Maybe I misunderstood you. I thought you were referring to quantity demanded in a perfect competition model where wages and prices fall at exactly the same rate. Later I addressed the monopolistic comp case. That works equally well for my MOA approach.

You said;

“For the last time, if NGDP means P*Y and not M*V, and if “the output market doesn’t really matter” – then it is meaningless to say that wages/NGDP “causes” anything. We are holding W/P constant, because WE AGREED THAT THAT WAS A SEPARATE FACTOR IN CAUSING RECESSIONS, which we are leaving to one side.”

When I say “output” I mean Y, not PY. I believe changes in PY cause changes in Y

You said;