The monetary base is special

Tyler Cowen has a new post criticizing the idea that we should eliminate hand-to-hand currency so that the Fed could cut interest rates below zero. He’s right that it’s a bad idea, but not all of his objections are sound:

Furthermore, under some views, this proposal would in essence put monetary policy in the hands of the drug trade. Cracking down on drug lords, or easing up on them, would become major monetary policy instruments, at least if you take the Fama-Sumner view that currency has special potency over the price level.

4. I do not myself believe that currency per se has such extreme power over aggregate demand, at least not in such a credit-intensive economy as ours. That means this proposal doesn’t get at the heart of the AD problem, which is closely linked to credit creation.

This is a very common mistake, so it’s important to explain what’s wrong with this reasoning. Money is not special because it is a big part of wealth, or a big part of credit. Indeed it’s not even special because it’s the medium of exchange. It’s special because it’s the medium of account. All prices (including the price of credit) is measured in money terms, not credit terms. If everything was measured in apple terms, then the apple market would drive the nominal economy (even though apples would continue to have only trivial impact on long term RGDP growth.)

Even if there is no change in the real demand for credit, a doubling of the money supply will lead to a doubling of the nominal credit stock in the long run. That’s true even if the stock of credit is 100 times larger than the stock of currency. The reverse is not true. Base money is special because we price things in terms of base money. If someone could show me that the previous sentence was wrong, I would disavow everything I’ve written on this blog from day one. It’s the rock on which all of monetary history theory is built.

Also note that drug dealers would not cause any problem for monetary policy, for the simple reason that they did not do so before 2008, when 95% of the base was already currency. The Fed can easily accommodate changes in the demand for currency, and does so. That’s why the big increase in currency demand in the 1990s and 2000s did not put us in a depression. On the other hand if we had been following a 4% constant MB growth rule, we probably would have fallen into depression as foreign demand for our currency soared.

6. I don’t see how this proposal could work unless it is applied globally, which seems implausible. If your dollars are being taxed some extra amount, just put them in a foreign bank to earn zero or do some kind of funny quasi-repurchase agreement, with a foreign bank, to avoid having formal ownership of the dollars on the days of the tax.

If I’m not mistaken the electronic money proposal would eliminate hand-to-hand currency, and all other base money would be electronic accounts at the Fed or money embedded in debit cards representing electronic accounts at the Fed. Continual positive or negative interest would occur via adjustments in those money balances up or down. Other foreign “dollar bank accounts” could pay positive or negative interest. So I think it would be feasible, but I’m far less confident on this point than on my previous point.

Currency will obviously be eliminated at some point, but I agree with Tyler that it would be a mistake to rush this solution into effect anytime soon. For now a much easier solution to our problems is monetary stimulus. Remember, Bernanke does not say the Fed can’t give us 3% inflation; he says it would be a bad idea.

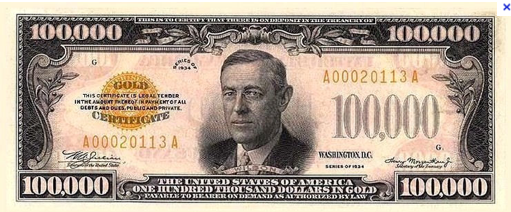

PS. The “Sumner-Fama view” is not all that special. During the Great Moderation the standard view was that the Fed could target NGDP or inflation via adjustments in the fed funds rate. And those adjustments occurred only because the Fed was able to adjust the base (not via a magic wand.) And the base was 95% currency. Furthermore, the vast majority of monetary economists believe the policy could have been implemented without reserve requirements, which is simply a tax. In that case the base would have been over 99% currency. Currency seems unimportant because actual operating procedures make the base change first, and then currency endogenously adjusts to a change in the base. But prior to 1914 the base was 100% currency, and we could easily return to that system and still run monetary policy essentially the same way. The only difference would be that the Fed would give banks ten $100,000 bills for a $1 million T-bond, not credit their Fed account for $1,000,000. That’s a trivial difference.

Monetary policy is all about adjusting the stock of currency.

Tags:

28. October 2012 at 06:14

Once again, money determines NGDP because it is the unit of account. But because money is also the medium of exchange, drops in NGDP cause recessions:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/05/imagine-theres-no-money.html

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/03/do-keynesians-understand-their-own-models.html

(more links coming up)

If everything was measured in terms of apples, then apples would drive the nominal economy. But a fall in apple production would not cause a recession, as workers wouldn’t be paid in apples.

Base money is special because we price things in terms of base money. But base money is also special (and potentially calamitous in its consequences) because all media of exchange are derived from the circulation of the stock of base money.

Ask yourself: why do nominal shocks have real effects? Because the price level doesn’t adjust. Why not? Because wages are sticky. So what? Well, if wages are sticky, and NGDP goes down, then a fixed hourly wage means less hours of labor hired.

STOP RIGHT THERE. Why hire less labor? Why not hire the same hours of labor? Because you can’t afford to. Why not? Well if NGDP is going down, then wages times hours worked is income, which is down, so one of the two must fall, if not wages then hours. But that’s not right – NGDP is nominal output sold for money. And it’s not just “nominal income” – it is the total value of income earned as money, measured in terms of money.

Otherwise workers could just barter, and we’d still have full employment.

28. October 2012 at 06:19

“The Fed can easily accommodate changes in the demand for currency, and does so.”

Except during 2008, of course…

(I’m taking demand for the higher aggregates as implicit demand for, well not currency but for the base.)

28. October 2012 at 06:21

But your criticisms of Tyler are all correct, of course.

More links: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/09/mackerels-and-money.html

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/05/why-an-excess-demand-for-money-matters-so-much.html

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2010/10/the-paradox-of-thrift-vs-the-paradox-of-hoarding.html

28. October 2012 at 06:22

Nick Rowe is one of the few people who properly understands macroeconomics. Really makes you laugh looking at all the respected economists who nonetheless don’t understand these things.

28. October 2012 at 06:31

Saturos, I mostly agree, although I’d add that massive goald haording caused a depression in the 1930s, even though gold was only rarely used as an actual medium of exchange by that time. A drop in apple production would cause a drop in NGDP. If wages were nominally sticky (in apple terms) unemployment would soar even of the stock of currency was unchanged.

28. October 2012 at 06:45

Hmmm, wasn’t the availability of the money of the 1930’s (US dollar currency and deposits) determined by the stock of gold?

If the unit of account was apples, but the medium of exchange was a certain kind of paper, then a fall in the stock of apples would require the apple price of everything else, and the nominal value of the incomes of the people producing everything else, to fall. But what matters for employment is the ratio of (the nominal value of) media of exchange to )the nominal value of) total output (and the factor payments behind it). So as long as the price of pieces of paper (the medium of exchange, in the example) adjusted to the stock of accounting-units (apples), so that the nominal value of the stock of exchange-media stayed constant, there would be no “general glut”, and no demand-side unemployment.

28. October 2012 at 06:48

To clarify, Tyler is wrong because the stock of “credit” (the higher monetary aggregates) is determined by the stock of base money (reserves, unless we abolish them). Even without reserve requirements, M3 can’t keep rising and rising whilst M0 is held constant, contrary to what Ritwik thinks.

28. October 2012 at 06:53

“So as long as the price of pieces of paper (the medium of exchange, in the example) adjusted to the stock of accounting-units (apples), so that the nominal value of the stock of exchange-media stayed constant, there would be no “general glut”…”

I’m surprised that I even need to tell you this, considering that you know how we (nearly) got out of the Great Depression…

Of course, IOR complicates matters. We should really be talking about the stock of non-interest bearing base money.

28. October 2012 at 07:04

Oh, and in case you were looking for a test of this theory…

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2011/03/unemployment-recessions-and-barter-a-test.html

Take that, mainstream economists! Who’s the scientist now?

I want to also add that Krugman’s baby-sitting co-op is not a great illustration, it is a model of credit, not money…

28. October 2012 at 07:07

The fundamental issue I have with most Keynesians, I guess, is that they go on about “Spending!” without immediately also thinking, “Money!”. Now that’s cognitive dissonance for you.

28. October 2012 at 07:11

Scott,

What is your opinion about the idea of private currency being issues by commercial banks as part of the broader money supply and not base?

28. October 2012 at 07:13

Saturos, I disagree. What matters is the ratio of NGDP to nominal hourly wages. If there is a big drop in apple output, then the value of apples will rise, producing severe deflation (and falling NGDP), regardless of what happens to the money stock.

If hourly nominal wages are sticky, then hours worked will fall.

The currency stock in the US rose sharply between 1929-33.

28. October 2012 at 07:16

Think of your standard Intro to Macroeconomics classroom. The first thing they teach is the circular flow of income. Goods go one way, money goes the other way. One can’t happen without the other.

They then proceed to completely forget this and start going on (a few weeks later) about C + I + G + NX = Y. As if it was handed down to them on a stone tablet (Which it kind of was). When they say “monetary policy”, you might get excited – wow! Are they about to reacknowledge the fact that all trading takes place with money? No, they just want to say that I is a function of i, and there’s a bunch of guys in the capital who decide every few months what i is going to be, so let’s see how much that would shift this curve…

We then end up at the zero lower bound, and resorting to arguments about how the price level might still be influenced by the time-path of the nominal interest rate as t tends to infinity… (Ah, but don’t you see, interjects the post-Keynesian, money is really all credit/debt, and households right now are all overindebted and deleveraging…)

28. October 2012 at 07:16

Joe, There’s no good reason to allow them to issue paper currency, unless we auction off the rights to do this. Otherwise you are just throwing away seignorage.

28. October 2012 at 07:39

Scott –

“Joe, There’s no good reason to allow them to issue paper currency, unless we auction off the rights to do this. Otherwise you are just throwing away seignorage”

As the unofficial seignorage advocate of this site, I’d like to point out that your point applies to the broader money supply as well – or at least the portion that’s backed by the Fed and FDIC.

Perhaps we should auction off rights to have an emergency line of credit at the Fed discount window and to have FDIC protection. Then the government would be getting the full seignorage profit for the entire money supply, not just base money. Another way to go is to have all government backed accounts 100% reserve (I know we’ve discussed this before and you’ve expressed at least some sympathy for the idea).

Saturos –

“Of course, IOR complicates matters. We should really be talking about the stock of non-interest bearing base money.”

Exactly. A higher level of reserves means more of a share of the profit from the monetary system (seignorage) goes to the government(and taxpayers), a lower share means a higher share goes to banks (and depositors, shareholders). How much of a share each group deserves and receives is a very important question for society.

28. October 2012 at 07:57

I see that Saturos has already put forward my position!

Scott: Yes, the fact that the base is the unit of account is important. But if that’s all it was, and if we lived in a barter economy, it would be perfectly possible for all prices to be sticky in terms of the base, for the base to halve, so there is an excess demand for the base, but the rest of the economy could continue on as before, with no recession, with people bartering one good for another at exactly the same relative prices.

The base is the unit of account. Plus, it’s a medium of exchange, and all other media of exchange are at fixed exchange rates with respect to the base.

(Saturos: in Paul Krugman’s babysitting model, since the tokens are the only asset, as well as being the only good acceptable in exchange, it is impossible to distinguish between money and credit. Those tokens are both money and bonds.)

28. October 2012 at 08:05

On second thoughts, here’s a weird model:

Suppose the base is the unit of account but not a medium of exchange. But all media of exchange are convertible on demand into the base at a fixed exchange rate (asymmetric redeemability). A excess demand for the base would create an excess demand for media of exchange, and cause a recession that way.

Analogy: suppose Canada fixes its exchange rate against the USD. An excess demand for US dollars will create a recession in Canada, even if USDs are not used as a MOE in Canada.

28. October 2012 at 08:23

Nick, Saturos is wrong. If apples are the medium of account then the apple market determines the price level. The base (including currency) is then endogenous.

Recessions occur if prices are sticky. If they are flexible then the effect of apple market shocks is purely nominal.

I agree with your comment on Krugman’s model.

Nick, Yes, I agree with your second comment. Although I’d prefer you call the base the “medium of account” not the “unit of account.”

In the 1930s gold was rarely used as a medium of exchange in Canada. But the rise in the value of gold (internationally) made a big fall in Canadian NGDP inevitable. There was no policy for the medium of exchange that could have prevented that, short of Canada changing their medium of account away from gold (which they eventually did.)

Negation, I’d rather abolish FDIC. But I agree that bank liabilities are effectively socialized in America. And the profits on the asset side of the sheet are privatized.

28. October 2012 at 09:16

Okay, Scott, get ready for a mega-comment… (I’m no Nick Rowe, but I’ll do my best.)

If we’re still assuming that apples are the unit of account, but not the medium of exchange, then I don’t think you are quite correct. Apples are not being used to intermediate exchange on all markets, they are only being traded on one or two markets. The price of apples is determined by supply and demand on that market.

Now suppose the supply falls (flow of new production falls, obviously apples are perishable and don’t make for much of a stock). Now to restore equilibrium the price must rise. Because apples are the medium of account, this means all other prices would fall. If they can’t (hold the price level fixed Keynesian-style) then the price of apples cannot rise. So we have disequilibrium trade in the market for apples, with a shortage of apples relative to quantity demanded.

But would this lead to unemployment? I don’t see any reason why it would. Greenbacks are the medium of exchange. The stock of greenbacks is unchanged. Everyone is holding the same inventories of greenbacks in their wallets and bank accounts (actually some nifty behind-the-scenes intermediation going on in those bank accounts), and the flow of greenbacks intermediating all exchanges is uninterrupted. Firms still receive the same volume of greenbacks in their annual revenues. Furthermore, since the exchange rate between apples and greenbacks is constant, the apple-value of greenbacks is also unchanged. Workers can ask the same hourly wages and be hired and paid for the same number of hours. But there is a disequilbrium in the market for apples.

OK, let’s be a little more realistic. Suppose apple prices do adjust upwards, and goods prices do fall. But hourly wages are fixed. And the price of greenback falls with the price of other goods. So if apple prices double, then the price of greenbacks falls in half. The goods market stays the same, but since the apple value of the greenbacks is halved the apple value of the goods they are traded for is also halved. There is equilibrium in the apple and the goods market. But not in the labor market, as the price of labor stayed fixed. Labor is now relatively twice as expensive as it was (twice as much goods-in-general being asked for an hour’s work), so half as much (or less) is hired. The economy implodes. I suspect this is what you are thinking of, a case where some prices but not others are sticky, so that when the value of the unit of account changes, some of the values in the rest of the economy adjust, but the others don’t, and there are gluts in the sticky sectors (labor). It comes down to a change in the value of money raising the real wage (due to money illusion) and pricing people out of work.

But the real world is somewhere in between. Suppose apple-NGDP falls in half. But suppose output prices, perhaps constrained by sticky wages, fall only a third. Now real wages, inversely, rise only by 50%, instead of doubling. (Assume the elasticity from the previous case, where doubling would have moved us up the labor demand curve until quantity demanded had fallen in half). But since NGDP has fallen by half, output-sales must still fall by a quarter, in addition to the 1/3 reduction in price. In that case, (assuming [unrealistically] 1-1 correspondence between % of output sold and labor hired) we would see employment fall by half.

Specifically, the 50% jump in real wages would put a third of the labor force out of work. But the additional 1/4 reduction in sales would lead to another sixth of the workforce being laid off, as the labor demand curve shifted to the left (zero-MRP workers excluded). So part of the unemployment is attributable to Sumnerian real wage increase, and part due to Keynesian lack of spending on the output that those workers would otherwise have been hired to produce.

But I have changed the story here slightly. Weren’t we saying that apples were only the unit of account, not the medium of exchange? If so, then the above is incorrect. It should be a combination of the previous two cases. So now suppose that as apple supply halves, with unit-elastic demand for apples, output prices adjust down by a third, but wages are fixed. But now the output market clears (at 2/3 of the price), even though the apple stock is halved. Because output prices didn’t adjust all the way, the apple price hasn’t risen to equilibrium, and there is an apple shortage. But this shortage has no further impact on the other markets. Because the apple value of spending only falls by a third, and the reduction in the flow of the medium of exchange (NGDP) is not equal to the reduction by half of the stock of unit of account (though money demand is constant) and all the output is sold at a third of the price, real wages rise by only 50%, and a third of the labor force is fired. And nothing else happens. So even though we halved the money stock, just like the fully flex-price case (and demand curves for apples and greenbacks were unchanged), this time we only got 1/3 unemployment.

So here’s the difference between our stories: in your story, it is the downward adjustment of some prices but not others that causes the problems. But in my story, where money being the medium of exchange also counts, to the extent that nothing adjusts downward, the recession and unemployment is even worse, as now the reduced flow of the medium of exchange (or “NGDP”, as you will) buys even less output, and the labor behind it. Real wages don’t have to change at all; there is less demand for labor even at the same real wage, because its product is going unsold. But this only occurs if money is the medium of exchange; otherwise there could be barter, and the output would still be “sold”, if not for money.

We are both right, in other words – unemployment is partly higher real wages due to assymetric adjustment to an appreciating unit of account, but also partly lower sales of output as output prices don’t fully adjust, causing unemployment of the workers behind the unsold output (but only because output must be sold for the medium of exchange). Remember, deflation is a substitute for [output-]recession. As long as output and greenbacks are equiflexible in price, there is no general glut regardless of the apple price, and no general-glut unemployment (though rising real wages could still put people out of work). On the other hand if the stock of exchange media falls, then holding money demand constant the flow also falls. If output prices don’t fall by as much as the money stock, then Y takes a hit, and this puts people out of work. Two different results, depending on whether money(=apples) is the medium of exchange or not.

It’s all a lot clearer if you draw it up on an AS-AD diagram. That’s the way I always think about it.

(God, how can MF do this all the time without cringing)

28. October 2012 at 09:24

“The currency stock in the US rose sharply between 1929-33.”

Yes, but M2 shrank by 1/3. And that was determined by the base and its velocity/multiplier. Eventually a sufficient expansion of the nominal value of base * velocity began to restore output, even without a recovery in the multiplier.

28. October 2012 at 09:36

Recessions occur if prices are sticky. If they are flexible then the effect of apple market shocks is purely nominal.

Oh Lord, now what are you saying? Suppose no prices adjust. Then apple prices, logically, also don’t adjust. But apples are not the medium of exchange. So changes in the stock of apples don’t affect the price of apples. So changes in the stock of apples don’t affect the nominal value of whatever the medium of exchange is. So you could withdraw as much “money” from the system as you like (well perhaps not all of it) but the nominal value of exchange media stays the same, nominal revenues are the same, and nominal wage payments stay the same.

On the other hand if apples are also the medium of exchange (or the medium of exchange has fixed redemption for apples, as Nick suggests) then throwing out half the apples cuts the stock and flow of media of exchange in half (unless people change their demand for holding inventories of media of exchange, or desired velocity), and now we do get a recession and unemployment. This whether prices adjust down with fixed nominal wage-rates, so that real wage payments are too high to hire everybody; or whether nothing adjusts, but the flow of revenues dries up and hence the availability of means to pay workers, even at the same wage-rates and price level (because you can’t barter).

Maybe Bill Woolsey could help out here, I suspect he agrees with Nick and I more than you here.

28. October 2012 at 09:36

Nick, thank God you’re here! Please help Scott see reason! If someone as smart as Scott can’t get this (which has been intuitively obvious to me since high-school) then I am going to have to give up on humanity.

I’m going to bed now, but tomorrow I’ll post a critique of why Krugman’s model is off (almost biased towards “Keynesianism” over “Monetarism”…)

28. October 2012 at 09:56

Sorry, it is possible for apple prices to rise whilst output prices stay fixed. It simply means that the apple price of greenbacks (exchange media) falls. Which means that the nominal volume of exchange media flow falls. Which will cause a recession, since output prices haven’t fallen.

Instead if output prices (in terms of apples) are fixed, and the exchange rate and volume of greenbacks to output stays the same, then an apple supply shock, holding demand for apples and greenbacks constant, causes an apple shortage at a fixed exchange rate of apples-to-greenbacks. Unlike a medium of exchange shock, however, this does not cause unemployment, as apples aren’t traded in all markets.

Sorry, can’t make it clearer than that.

“There was no policy for the medium of exchange that could have prevented that…”

Sure there was. Devalue the medium of exchange, in terms of the unit of account. Like FDR did. This would increase the nominal value of the total volume of exchange-media-flow, so that output prices could come back up to normal, in line with those sticky wages. And the medium of exchange could flow through, and buy up all the output, and the inputs behind them…

Why isn’t this obvious to everybody???

28. October 2012 at 10:02

So changes in the value of the unit of account can cause a recession by:

a) pulling output prices down whilst wage-rates are fixed, real wages rising (this may only be a labor-market recession though)

b) reducing the nominal price of the medium of exchange, meaning a reduction in the nominal flow, leading to a general glut and unemployment for workers whose products can’t be sold.

But if there is no medium of exchange, with everybody bartering using apples as a measuring-stick, then b) can’t happen, and there are no general-glut recessions. Like this one.

28. October 2012 at 10:10

What I’m saying is, you can’t have

a) unit of account appreciation

b) output prices fixed

c) no medium of exchange, or no change in value of the medium of exchange

That’s an impossible trilemma (logically impossible).

28. October 2012 at 10:44

Saturos, You said;

“Sure there was. Devalue the medium of exchange, in terms of the unit of account. Like FDR did.”

We are talking past each other. I was assuming gold is the medium of account. If you devalue gold then it’s not the medium of account, currency is. In that case I obviously agree with you.

I am assuming gold is the medium of account, and I’m also assuming that gold market was in equilibrium 100% of the time (which it basically was) so that any changes in the real value of gold must show up as changes in the price level.

Saying the real value of gold rises 25% is simply saying the price level fell 20%. It’s two ways of making exactly the same statement. It’s not some sort of weird theory I’m propounding.

You shouldn’t use the term “unit of account,” as it is confusing. You should refer to medium of account and medium of exchange. Unit of account is simply dollar or pound or yuan. It depends on whether the dollar is a one dollar bill, or 1/20.67 oz of gold.

If everyone is bartering you are probably assuming prices are flexible.

Here’s another way of looking at it: Suppose 1/2 of the world’s gold stock vanishes overnight, but gold is not the medium of exchange, and prices are sticky, so they don’t fall right away. In that cases expected future NGDP will fall in half, and thus AD will fall, which reduces current NGDP and RGDP.

In the 1930s M2 fell for the same reason as NGDP fell, the rise in the real value of gold caused by gold haording caused deflation all over the world. M2 is endogenous, indeed even the base is endogenous under a gold standard.

28. October 2012 at 12:56

Scott, you said:

If everyone is bartering you are probably assuming prices are flexible.

Both Nick and I seem to think that barter can occur even if the general level of prices is fixed in terms of the numeraire. It would just be really inefficient.

The gold market is in equilbrium 100% of the time”

Equilibrium in terms of what? What is on the other side of this market? If there’s no medium of exchange, then if the price level is fixed and half the gold disappears, there’s going to be an excess supply of goods in general in terms of gold. But that’s not a recession, as gold is not the medium of exchange. No one would have to lose their jobs.

If you want the gold market in equilibrium at all times and hold the price level fixed, then for the price of gold to rise you need a medium of exchange gold is traded for. Then a fall in the stock of the medium of account means a fall in the gold-value of the stock of the medium of exchange. Then you do get a recession, but it’s not the price of goods in terms of gold that does it, as gold is not traded for goods. It’s the doubling of the currency price of goods, to offset the halving of the gold price of currency, keeping the gold value of the price level fixed. But if currency wasn’t the medium of exchange, there wouldn’t be a recession.

But the US Gold Standard wasn’t like that. In that case it was the price of goods in terms of dollars that was sticky. By expanding the stock of the medium of exchange, output was restored. And because dollars were also the medium of account, prices rose too. But this meant accepting a higher dollar price of gold. If gold had been the medium of account, then this wouldn’t have worked – devaluation would have raised the size of the medium of exchange stock but lowered its nominal value, in terms of gold. NGDP would not have risen. (If gold had been the medium of account then only changes in the gold stock could have affected the nominal value of output.)

So if gold is really the numeraire then the gold stock determines the effective stock of the medium of exchange, if there is one (whether gold itself or not). And it is fluctuations in that effective stock which cause recessions. But ignore that medium of exchange and you can’t hold the price level fixed and say that the price of gold changes, nor that gold causes recessions. So…

Here’s another way of looking at it: Suppose 1/2 of the world’s gold stock vanishes overnight, but gold is not the medium of exchange, and prices are sticky, so they don’t fall right away. In that cases expected future NGDP will fall in half, and thus AD will fall, which reduces current NGDP and RGDP.

That’s false if there’s no medium of exchange, and true if there is, but only because the value of the stock of currency is determined by the gold stock (medium of account stock). To see this, imagine that gold demand wasn’t unit elastic. Let’s say a halving of the gold stock led its price to triple. Then then the money stock M (currency, or the medium of exchange) is three times smaller. V = 1/k, where k relates to the quantity of currency people want to hold, not gold. Let’s hold V and k constant. NGDP will fall threefold, not in half. So gold cannot be money. So money is the medium of exchange, not the unit of account. QED.

OK, I think I’m done now 😉

28. October 2012 at 13:12

ssumner

Speaking of common mistakes, this quote right here is a very common mistake.

Money as a “medium (i.e. unit) of account” is subsidiary to its medium of exchange use. This is rather easily understood as soon as one considers what would happen to one use if the other use were to be eliminated. For example, if the use as a medium of exchange were to be eliminated, then its unit of account use would all but be eliminated as well. But, if its unit of account use were to be eliminated, it would not require its medium of exchange use to be eliminated. People can continue on trading goods as against the money commodity without technically “accounting” for it in the unit of account sense.

I don’t think you addressed the argument Cowen actually made. He argued that currency is not a significant form of money in an economy such as ours where money is mostly fiduciary media (i.e. credit). Cash transactions are dominated by electronic exchanges which trade fiduciary promises from banks. As such, currency (base money) manipulation by the central bank does not adequately address the “AD problem”, because most of what AD is composed of is not currency based spending. Not saying I agree with any of this, just that this is what he seems to actually be saying.

This is incorrect. We don’t price things in base money per se, we price things in money, which is composed of both base money AND credit expansion. This is easily understood as soon as we realize that credit expansion is a crucial component of nominal demand, and nominal demand is one “half” of what determines prices (the other “half” being supply).

Good lord, are you sure? Even if you’re wrong here, it doesn’t imply your entire NGDP theory is wrong (although it is).

The reason why this doesn’t imply your worldview is wrong is because NGDP is determined primarily by the monetary base. As you focus on NGDP, you are really focusing on the aggregate money supply, which is the primary driver, and the aggregate money supply contains both base and credit, with the former driving the latter. It all fits, as far as it goes without too much criticism.

28. October 2012 at 13:25

I strongly favor the privatization of hand-to-hand currency. A coercive monopoly on the issue of hand-to-hand currency is wrong. Banks and their customers have a right, as an implication of freedom of contract, to create redeemable hand-to-hand currency. That this competition will result in the end of monopoly rents is desirable. I don’t beleive that the government should auction off the right to be the monopoly issuer of currency.

How exactly will competitive issuers of hand-to-hand currency provide benefits to those holding the currency? I am not sure. There are many possibilities. Still, I think the most reasonable approach is for banks to continue to interest to those withdrawing currency and putting it into circulation until the currency clears.

Still, having many ATM machines and providing free withdrawals to everyone (including the customers of other banks) is another possibility.

To me, monopolizing currency is stealing interest from those who use the money. People who are paying fees to get currency from an ATM machine are bearing the burden of the government currency monopoly.

In my view, Sumner’s views on this are based upon old Chicago notions–government prints money and spends it, 100% reserve banking, and a money supply rule.

The fundamental nominal value in that system is the nominal quantity of money. There is no relationship between banking and money. And if velocity is constant, nominal GDP grows at a stable rate.

With nominal GDP level targeting, the fundamental nominal value is the level of nominal GDP. The quantity of currency must vary, and it could fall to an arbitrarily low level. Sumner admits that one day it will happen. This makes it a type of borrowing.

The benefit to being the monopoly issuer of currency is that you can borrow at a zero nominal interst rate and a real interest rate equal to the negative of the inflation rate. No doubt this is good for a monopoly issuer.

With a competive system, the benefit goes to those using the currency. If you think about it, there are lots of benefits that a bank can provide to those using its currency.

But one clear macroeconomic benefit today is that deposits and credit would not be based upon privately issued currency. If banks stop issuing it, and shortages develop, this is no barrier to spending on output remaining on a slow, steady growh path.

28. October 2012 at 13:44

There is no way for apples to serve as the medium of account unless the medium of exchange is somehow tied to apples. The easy way is to make money redeemable with apples.

There is a shortage of apples at the defined price. Those holding money redeem it for apples. The quantity of money falls. There is a shortage of money. Spending on output falls due to the shortage of money (not the shortage of apples directly.) If apples are a normal good, the demand for apples falls. The apple market clears.

As the prices of other goods fall, and the relative price of apples rise, then there is a surplus of apples at the low level of real income. Apples are deposited for money, the quantity of money rises, spending on output rises, real output recovers.

In the end, the price level has fallen enough to clear the apple market. Nominal wages (in apple terms) have fallen (perhaps to a lower growth path.)

Now, I will grant that as soon as the apple blight hits, everyone will expect a recession and deflation. Spending on output will drop immediately.

But if there we no connection between apples and money, there would be no process to keep the price of apples from rising above its defined price. There would be no process that would cause spending on output to fall and the prices of other goods to fall. And so, there would be no room for expectations to directly impact spending on output and the prices of other goods.

I have worked out the scheme hinted at by Saturno, where we have a fiat money whose price is determined on the apple market in the usual way, though rather than “dollars per apple” we say “apples per dollar.” And then, amount of money required for all other goods and services is calculated using prices quoted in apples and the apple price of a unit of paper money. Even then, the nominal quantity of money (in apples) changes creating the monetary effects needed to adjust the price level.

Still, the realistic scenarios involve direct or indirect redeemability.

Currency serves as money itself, but it is tied to the broader payments system by redeemability. And so, it can tie down the price level.

However, I think the thought experiement of a given quantity of currency determining the price level (or nominal spending on output) is the wrong way to think of a system where nominal GDP (or the price level) is the nominal anchor.

If the demand for currency was zero in equilibrium, changes in the quantity of currency could be used to keep nominal GDP on target, as long as the monetary authority can settle up checks (paper or electronic) with currency and insist on the settlement of such claims with currency.

And, of course, deposits can do just as well as currency, though with the benefit of being able to adjust the interest rate paid on it as well as the quantity.

28. October 2012 at 13:55

Monetary policy is all about setting the real interest rate on the financial numeraire.

28. October 2012 at 14:14

I don’t doubt for a moment that price levels are set primarily by the base money supply, but it isn’t just the current level of base money so much as the expected level of base money now and in the future. I think these expectations can be influenced by the level of credit in an economy, because excessive debt overhangs can induce the central bank to make more base money available. The causation between increases in broad money (or even credit) and increases in base money often runs opposite to what the textbook money multiplier model implies.

28. October 2012 at 15:01

Sarturos, I think you are getting confused by the fact that currency is usually pegged to the medium of account at a fixed price. In that case the deflation can be equally well thought of in terms of a rise in the value of gold or a rise in the value of currency. Then you add in that currency is closer to the transactions, and it seems more “important.” But that’s an illusion. One could imagine a regime where the currency does not trade at a fixed price to the medium of exchange. In that case which would determine the price level? Obviously the medium of exchange (say gold), not the currency. You could price wages and prices in terms of gold and have the Zimbabwe dollar serve as your medium of exchange. Prices would be listed in gold terms, and at the cash register there would be a list of the current exchange rate between Z. dollars and gold. That would be a clumsy system, but it shows that the medium of account, not the medium of exchange, is the sine qua non of money.

If you want to view gold and currency as dual media of exchange, you can model the price level in terms of either market. By analogy, if oranges and tangerines were perfect substitutes (and hence had identical prices), then it would be possible to describe the path of tangerine prices with 100% accuracy by describing shifts in the supply and demand for oranges.

Bill, No, I don’t favor 100% reserve requirements, I favor zero. And in 1995 I published a paper that called for “Privatizing the Mint”. But I advocated auctioning off the rights to produce various denominations, as price competition is almost impossible in currency, and I wanted to avoid wasteful non-price competition. Remember when banks gave away toasters?

Bill, regarding your second point, let’s avoid a lot of confusion by using gold as the medium of account, so there’s no doubt about the mechanics of convertibility, and we can refer to known real world examples.

Ritwik, And what was that rate during the Zimbabwe hyperinflation?

Rademaker, I certainly agree about the textbook multiplier model. And I certainly agree that it’s the future path of monetary policy that matters. But I’d argue that the Fed usually responds to shifts in the demand for base money, and tries to keep the path of bas emoney along a line that stablizes some combination of P or NGDP. I don’t think they target credit aggregates (although I wouldn’t completely rule out the hypothesis.

28. October 2012 at 16:03

Saturos:

Two reasons: Self-esteem and fast typing.

28. October 2012 at 16:06

Scott Sumner,

“Bill, No, I don’t favor 100% reserve requirements, I favor zero. And in 1995 I published a paper that called for “Privatizing the Mint”. But I advocated auctioning off the rights to produce various denominations, as price competition is almost impossible in currency, and I wanted to avoid wasteful non-price competition. Remember when banks gave away toasters?”

I need to re-read that paper, but couldn’t one have non-price competition in the form of new denominations e.g. private low denomination coins, as documented by Selgin in “Good Money: etc.”?

28. October 2012 at 22:45

Scott

-1000%, give or take a few hundred percent, in early 2007, about a year before *hyperinflation* finally hit.

28. October 2012 at 22:57

Wasteful nonprice competition.

For example, restaurants offering many convenient locations and a variety of menus when it would be oh so efficient to have a few rationally located restaurants with a standardized menu.

I am familiar with your paper (of course,) and considered it wrongheaded at the time.

Under modern conditions, competing banks issuing hand-to-hand currrency have lower costs (because of less need to hold vault cash) and more revenues from earning assets. They compete to get customers by paying them higher interest on deposits. This is on the very reasonable assumption that it is your depositors that withdraw and hold your currency and then when it is spent, it may pass hand to hand to various people until it finally clears.

Your borrowers, on the other hand, are going to have little interest in taking a large amount of currency anyway, and when they do get the loan, they will spend the funds and it will rapidly clear.

Of course, there might be descrimination. For example, retailers get extra high interest on their deposits (or lower net service fees) because of their use of currency and their ability to launch it into circulation. Those banks with lots of retailers as customers do better, and pay higher deposit rates or charge lower fees to them.

As I have explained many times before, under modern conditions, it would be possible to record the serial numbers of currency as it is paid out of the ATM machine, and interest could be credited to the customer withdrawing it until it clears. If you hold your own banks currency, you earn interset on it. When you spend it, you still earn interest until the seller deposits it and it clears.

When I think of “waste” it would mostly be lots of ATM machines in convenient locations, along with no fee services to the customers of other banks.

I don’t see the toaster example as too relevant.

28. October 2012 at 23:20

It is possible to devalue the medium of account. The medium of account is the good used to define the unit of account. The price of the medium of account is fixed by definition. Devaluation means raising the unit of account price of the medium of account.

If you say the dollar is 1/20 of an ounce of gold, and then change it so that it is 1/35 of an ounce of gold, then there is a devaluation.

If the medium of account is the medium of exchange, then monetary effects are automatically generated so that price level adjusts to clear the market for the medium of account.

If, on the other hand, the medium of account is not the medium of exchange, there must be some tie to the medium of exchange or else the price level will not adjust.

Suppose gold is the medium of account. The demand for gold rises at the defined dollar price. There is a shortage of gold. What market process causes all of the other prices in the economy to fall so that the realtive price of gold rises enough to close of the shortage?

The gold shops have empty shelves. Why does this make the grocery store lower its prices?

With a Walrasian auctioneer, we just assume that he calls out lower prices for other goods until the gold market clears.

If you assume the Walrasian auctioneer is prohibited from calling out lower wage rates, then I guess that real wages rise and firms choose to hire fewer workers.

But there is no Walrasian auctioneer.

Why does the grocery store cut its price? The only plausible mechanism is going to be reduced demand for groceries. Why does empty shelves in the gold shop cause people to spend less on groceries?

In reality, money was convertible into gold, and so, people wanting gold could go to their banks and redeem money for gold. The quantity of money falls. The demand to hold money didn’t change, and so there is a shortage of money. Each person can rebuild their money holdings by spending less, including less on groceries.

When this leads to the prices of all other goods falling enough, then the relative price of gold has risen, and the gold shortage ends.

Now, once this monetary link is estabilished, it can be bypassed by expecations. The shelves start to empty in the gold stores. People expect a recession and deflation. They cut spending now, even before anyone shows up at the banks to redeem money for gold. The price level falls enough to clear the market for gold.

But if money was not redeemable for gold, then there wold be no recession and deflation. And so, there would be no reason to reducing spending now.

As Saturnos explained (and I guess he didn’t read the relevant chapter in my dissertation,) if there is no convertibility, but people buy gold with paper money, but quote prices in gold, then the gold store allows a gold price of paper money to be determined. It is just like normal. A shortage of gold, and the gold price of paper money falls enough to clear that market. Then, that gold price of paper money, along with the gold prices of other goods, is used to determine how much paper money is due for each other good.

But if there is a shortage of gold, the gold price of paper money falls, and so the nominal quantity of money (in gold units) falls. Alternatively, the amount of paper money due for all other goods rises, resulting in surpluses of them. And so, they reduce their gold prices (and their paper money prices too.)

Kind of a silly system, but it shows that it is monetary effects that determine the price level.

Again, it is possible that expectations of this process would leave everyone to immediately lower their gold prices as soon as they receive the report that the gold price of paper money has fallen. Which suggests they are really quoting prices in paper money, doesn’t it?

Oh, and by the way, if there is a shortage of money it causes a recession. But when the recession hits the gold shop, and it rasies the gold price of paper money, this raises the nominal quantity of money, fixing the problem.

28. October 2012 at 23:38

In fact, it’s even more interesting. In early 2004, when inflation was a mere couple of hundred percentage points per annum, the bank rate was about 80%.

http://www.rbz.co.zw/publications/monthlyeb.asp

Seems like a classic Howitt/ Wicksell collapse to me.

Saturos

The divergence of M3 from M0 is rather clear in Canada, NZ. Canada has even stopped reporting/publishing M0. The data’s all out there.

It’s also clear in the US, when you include MMMF/ shadow bank deposits in M3. (as you really should)

29. October 2012 at 00:49

Scott, we are very close to agreeing here, and hopefully you’re about to understand the argument I’ve been making, which follows from your last comment.

“One could imagine a regime where the currency does not trade at a fixed price to the medium of exchange. In that case which would determine the price level? Obviously the medium of exchange (say gold), not the currency. You could price wages and prices in terms of gold and have the Zimbabwe dollar serve as your medium of exchange. Prices would be listed in gold terms, and at the cash register there would be a list of the current exchange rate between Z. dollars and gold.”

This is exactly the scenario I used in my last argument. As you say, it would be clumsy, and the US gold standard didn’t actually work like this (as prices were sticky in dollar terms, not gold terms). Now, I agree with you that in this scenario, where gold is really the medium of account, the price of gold is what determines the price level. But that doesn’t establish anything: you are arguing that because the medium of account determines prices, it is money. You’ve drawn a substantive conclusion from a tautology. What I’m disputing is whether the medium of exchange, despite relying on the medium of account (which could be something else) to determine prices, nonetheless is the important factor in determining whether recessions occur. If it is, and if the “M” in the equation of exchange refers to the medium of exchange, not the medium of account, then I think that the good which should be called “money”, in a case where they differ, is the medium of exchange and not the medium of account.

So let’s say gold is the MoA, and dollar bills are the MoE. In my previous comment, I showed that it was the effective quantity of dollars that determined prices, not the quantity of gold, hence “M” in MV = PY is the (effective) quantity of dollars and not of gold. The quantity of gold only matters because it changes the price of gold, which inversely changes the nominal value of M(oE). If the gold stock halves, but the price triples, then the value of M falls to 1/3, not 1/2.

Similarly, k refers to the demand for dollars (MoE) not gold (MoA). We know that if k doubles, then ceteris paribus P halves. But can you see that k is not gold demand, but dollar demand? Hold the quantities of dollars and real goods constant. A doubling of the quantity of gold demanded, holding the stock fixed, means that the price must adjust upwards. Let’s say once again that the dollar price of gold triples, to clear the excess demand. The gold value of dollars falls to 1/3. And the gold price of goods (the price level) falls to 1/3. (Because gold was not the MoE, it wasn’t necessarily the case that halving the gold price of goods would lead to half as much gold demanded – people are holding inventories of dollars for exchange, not gold.) So the doubling of gold demand cannot have doubled k. So k is not gold demand.

Now let’s double the demand for dollars instead. People are trying to hold twice as many dollars at the current PY. But assume that the dollar demand for gold does not fall. The flow exchange of dollars for other goods halves. The quantity of dollars is constant. But the exchange rate between dollars and goods (the dollar price of goods) halves. And the gold price of dollars stays the same. But the gold price of goods halves (increasing real money balances to meet the demand). Even though neither demand nor supply in the gold market changed! This is possible because gold is not directly traded for goods; it’s only the MoA. [Of course in reality the gold price would also fall, increasing the value of M (dollars), and the price level would not change as much.] In this case it is clear that k is dollar demand. k doubles, P halves.

So which should be called the money of this economy: gold or dollar bills? I say the latter. Fluctations in the gold stock will cause recessions, by changing the value of M. Fluctuations in the dollar stock will change the size of M, but not its nominal value, and won’t cause recessions. But V is the velocity of dollars not gold. A change in the desire to hold dollars could cause a recession, even [especially] if the gold price didn’t change. On the other hand if dollars didn’t exist and there was no MoE then fluctuations in the gold price would not cause recessions. If the price level was sticky, then so too would be the price of gold. But excess demand for gold would not cause unemployment. Gold demand would not fall as a function of Y, as Y could always be bartered, and wouldn’t fall. The excess demand would persist, but no one would lose their jobs.

You need to remember that in a monetary economy the medium of exchange is on every market – including the market for the medium of account. That might clear things up a little.

But if this still doesn’t persuade you, then I’m afraid there’s only one thing that will – a Nick Rowe post. Over to him.

29. October 2012 at 00:54

Wider comment boxes, more readable fonts. This is such a popular blog, those changes would really help us commenters.

29. October 2012 at 01:06

“There is no way for apples to serve as the medium of account unless the medium of exchange is somehow tied to apples. “

Bill, in a barter economy, you could arbitrarily select apples as the numeraire, as Walras did, couldn’t you? Then the price of apples (or gold) is the inverse of the price level.

“I have worked out the scheme hinted at by Saturno, where we have a fiat money whose price is determined on the apple market in the usual way, though rather than “dollars per apple” we say “apples per dollar.” And then, amount of money required for all other goods and services is calculated using prices quoted in apples and the apple price of a unit of paper money. Even then, the nominal quantity of money (in apples) changes creating the monetary effects needed to adjust the price level.”

Yes, exactly. And M is the nominal quantity of the exchange media (measured in apples/gold), not the physical quantity of apples. Big difference. (I’m not proposing the scheme, it’s just to illustrate that money is the medium of exchange first, medium of account second. I see that’s the way you are using the word too.)

“Kind of a silly system, but it shows that it is monetary effects that determine the price level.”

Yep. Except remember that in this example gold, the medium of account is what Scott would call “money”, paper notes are just the medium of exchange. My whole point is to convince him that he should call the notes money, as you do, whilst the golden measuring stick is just a unit of account. It affects the value of the money stock, but is not itself money. Which makes a big difference in MV=PY, determining how price levels change and how recessions occur.

Bill, beginner’s question. How does the quantity of deposits, and broader means of payment, get tied down under free banking? What restricts the supply of reserve money? How is inflation controlled? (If you say competition between reserve-issuers, wouldn’t network effects lead to a monopoly emerging anyway?)

For example, Ritwik claims that the supply of M3 is unconstrained by the supply of M0. Suppose this were really true. How do means of payment that any bank can issue retain their value for everyone else? I don’t want a bank I hold shares in to pay me dividends in money that it can print as much as it wants of.

If lending actually created the means of exchange, then it wouldn’t really be “lending” would it? Of course, bank deposits are claims to reserve money, and as they circulate so do the reserves behind them. Hence bank runs. It’s conceptually clearer to think of money as the irredeemable liabilities in the economy – i.e. they’re not really liabilities at all.

I would love to read your dissertation, if I thought I could understand it…!

It’s Saturos btw.

29. October 2012 at 01:13

Oh, and by the way, if there is a shortage of money it causes a recession. But when the recession hits the gold shop, and it rasies the gold price of paper money, this raises the nominal quantity of money, fixing the problem.

We are clearly on the same page here (pun intended).

29. October 2012 at 01:20

There is money and then there is the numeraire. Our currency happens to be both. And since it is both, a shortage of it will cause a recession.

Can’t make it clearer than that.

29. October 2012 at 03:42

Saturus:

I don’t think Sumner thinks that the medium of account is money or that the equation of exchange applies to the medium of account.

Currency, on the other hand, is money and the equation of exchange applies to it, as well as it applies to anything. Currency is important because it serves as medium of account, not because it is money.

The other sorts of money, each one of which may not be terribly important, but which add up to something more important than currency as money, are not any of them the medium of account. And so, they don’t play the key macroeconomic role that does currency.

I think there is a lot of truth to that, but it only works because the other types of money are redeemable in currency. If they weren’t, then there would be no process by which changes in the quantity of currency or the demand to hold it would lead to a change in the price level.

What Sumner has emphasized, and I am sure that he is correct, is that expectations allow the process to be skipped.

An anticipated increase in the demand for currency, that people don’t expect to be accomodated by a greater quantity, will immediately beging putting downward pressure on the price level. There is no need for the demand for currency to rise first.

29. October 2012 at 03:45

P.S. And an unanticipated increase in the demand for currency, that people anticipate will be accomodated by an increase in the quantity soon, will create little or no downward pressure on prices.

29. October 2012 at 03:46

Saturos… I will try to get it right.

29. October 2012 at 04:59

“Currency, on the other hand, is money and the equation of exchange applies to it, as well as it applies to anything. Currency is important because it serves as medium of account, not because it is money.

The other sorts of money, each one of which may not be terribly important, but which add up to something more important than currency as money, are not any of them the medium of account. And so, they don’t play the key macroeconomic role that does currency.”

I’m reading this as your statement of Scott’s views. (Which I partly share.)

“I think there is a lot of truth to that, but it only works because the other types of money are redeemable in currency. If they weren’t, then there would be no process by which changes in the quantity of currency or the demand to hold it would lead to a change in the price level.”

And that is what you and I are emphasizing. And if you add expectations to the mix, then “the future can cause the past”, as Scott likes to say.

“And an unanticipated increase in the demand for currency, that people anticipate will be accomodated by an increase in the quantity soon, will create little or no downward pressure on prices.”

Yes, as people won’t be cutting back on spending of currency (and higher means of payment) in aggregate.

I would be having more self-doubts about my position on this, if it weren’t for the fact that both Bill Woolsey and Nick Rowe seem to agree with me (though of course I’ve learned plenty from reading them).

29. October 2012 at 05:00

Off topic… I think Bryan Caplan’s reasoning here is brilliant. (Am I stupid?)

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2012/10/a_bunch_of_argu.html

29. October 2012 at 05:50

Bill, I think you misunderstood my point. I certainly don’t claim that all non-price competition is wasteful, rather that non-price competition is wasteful when it occurs only because price competition is not possible. So I don’t see any relevance for the restaurant examples, etc. Restaurants can very easily engage in price competition.

You said;

“I don’t think Sumner thinks that the medium of account is money or that the equation of exchange applies to the medium of account.”

I most certainly do think the medium of account is money, and I do think the equation of exchange applies to the medium of account–indeed it’s a tautology.

You said;

“It is possible to devalue the medium of account. The medium of account is the good used to define the unit of account. The price of the medium of account is fixed by definition. Devaluation means raising the unit of account price of the medium of account.”

If you devalue the medium of account, then by definition it is no longer serving the role of the medium of account. Between April 1933 and February 1934 gold was no longer the medium of account.

You said;

“Suppose gold is the medium of account. The demand for gold rises at the defined dollar price. There is a shortage of gold. What market process causes all of the other prices in the economy to fall so that the realtive price of gold rises enough to close of the shortage?”

It’s no different from when there is a shortage of currency. Asset prices immediately adjust so that the demand for base money equals the supply. The same is true for gold. Maybe interest rates rise, increasing the opportunity cost of holding the medium of account (until prices have adjusted.)

Ritwik, I didn’t know you could have rates more negative than minus 100%. How is that possible? And is the Zimbabwe bank rate a free market interest rate? And how do you define monetary policy in an economy with no banks (which has been true for most of world history.)

Saturos, I’ll reply in a new post.

29. October 2012 at 05:57

A Visual Guide to the Federal Reserve: http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2012/10/guide-to-fed-reserve/

29. October 2012 at 06:27

Bill Woolsey:

That is an apt description of how money is produced and exchanged under the present non-market system, no?

One quantity of money is as efficacious as any other.

Also, it cannot be ignored that sudden increases in cash preference can be, and in our society typically are, preceded by undue increases in the supply of money, which affected the physical side of the economy via altering relative demands and prices that induced investors to allocate capital in unsustainable ways. This preceding inflation is usually presented at the time as intended to eliminate the deflationary price and demand effects at the time. So what ends up happening is that the “solution” begets the very problem it was intended to solve.

29. October 2012 at 07:08

A $10 note is a value that the Fed owes you. It is a credit, in the same way as a $10 deposit at the Fed would be.

The Fed may of course repay the $10 deposit credit with a $10 note, but it may conversely repay the $10 note credit with a $10 deposit.

So, the difference between money and commercial credit is not that they are different in nature, but that the former is emitted by a super safe borrower and carries no interest.

The first conclusion is that if the Fed pays an interest on deposits of commercial banks, it makes them a big favor. One that holders of notes can’t access.

The second conclusion is that it is possible to keep only Fed deposits and eliminate notes. That’s already happening in part in countries discouraging the use of cash (France for example).

So, in theory, the Fed could decide to apply negative or positive interests on deposits (because we’re talking deposits and not loans, a rate increase would be deflationary).

There may be reasons for not eliminating bank notes. But eliminating them would not eliminate the monetary base.

29. October 2012 at 07:15

Scott

My apologies, I forgot about the 1+i term in the denominator and ended up with a nonsensical result.

So, I should say that in early ’04, the real short rates in Zimbabwe were about (100% – 300%) /(1+300%)= -50%. Similarly, in early ’07 they were about (340%-2000%)/(1+2000%) = -80% approx.

The bank rate is not a market rate, of course. It’s not a market rate anywhere in the world. Would you call the fed funds rate a market rate? I’m not absolving the monetary and fiscal authorities of blame. Setting the real short rate IS monetary policy, so Zimbabwe was a case (partially) of monetary policy gone horribly wrong. Hyperinflations typically have so many factors happening together that I would personally eschew mono-thematic explanations anyway. I just wanted to take you on the Zimbabwe challenge, to show that real rates had become negative and set off an inflationary spiral for a longish time before the final currency collapse happened.

I’m just saying that for high inflations (say of the Lat Am variety) and even in the initial stages of hyperinflations, the process starts with a Wicksell/Howitt mistake. If you set the real interest rate too low for too long, government AND (crony) private sector credit explodes. Essentially, high inflation episodes are not just about a collapse in currency/deposit demand but also about an explosion of credit and spending demand.

I’m not knowledgeable about the conduct of monetary policy in medieval or ancient times so I will reserve comment on your other question. But I’m reasonably convinced that in the modern world, apart from being a somewhat Luddite behavioural legacy that lets governments make a little bit of free revenue, and facilitating crime, currency is not important.

29. October 2012 at 07:16

LOW INTEREST RATES

Market monetarists, and more and more of other Fed apologists/strategists, believe that the declining interest rates since 2008 are the result of a shift in real interest rates, that is, it is increased savings that is primarily responsible.

What if, however, we look at the long term trends? When we do that, we we see declining interest rates associated with a declining personal savings rate.

The recent decline in interest rates is being associated with the recent increased saving, and yet the decline in interest rates is part of a much longer term declining trend, which suggests that the notion of higher savings rate as the alleged cause is an illusion.

29. October 2012 at 07:32

MF, the US is part of a global capital market. You have to look at global savings. And the natural rate is currently low because no one wants to borrow, as well as the excess demand for safe assets.

Ritwik, you said, “Would you call the fed funds rate a market rate?”

He probably would.

29. October 2012 at 07:45

[…] seem obvious to me, but I can tell from the recent comments that most people don’t agree. Saturos and Bill Woolsey have argued (in the comments) that money is the medium of exchange. I argue that money is the […]

29. October 2012 at 08:04

Saturos:

MF, the US is part of a global capital market. You have to look at global savings.

No doubt, but the same declining savings rates is taking place in the world as well.

Plus, consumption spending has not declined in most of the countries that save in the US, which would have taken place if increased saving in the US really was the cause.

And the natural rate is currently low because no one wants to borrow, as well as the excess demand for safe assets.

Well, “no one” is an exaggeration, but total credit outstanding has declined, if that is what you are referring to.

Yet, if “no one wants to borrow”, then rates would be going up, ceteris paribus, not down, no?

29. October 2012 at 08:08

MF, tell that to all the economists who have been talking about a global savings glut for years.

“Yet, if “no one wants to borrow”, then rates would be going up, ceteris paribus, not down, no?”

Here you have lost the last vestige of sanity. (You also seem to have become French – perhaps not coincidentally.)

29. October 2012 at 08:18

Bill Woolsey –

“To me, monopolizing currency is stealing interest from those who use the money.”

I don’t see it that way. If I keep a few subway tokens in a drawer does that mean the transit authority is stealing interest from me? The transit authority is a monopoly issuer of subway tokens. Likewise, if people voluntarily want to hold US currency, they must believe it is in their interest to do so, and are entitlted to no interest .

Any insitution has a monopoly on issuing its own notes. If banks want to issue bills of credit, and it’s clear that they are not backed by, or accepted by the US government, I have no problem with that. People can trade them as they wish. But the currency that the government uses, backs, and accepts as payment must only be issued by the US government.

29. October 2012 at 08:21

Saturos:

MF, tell that to all the economists who have been talking about a global savings glut for years.

You mean Sumner, right? He argued a few posts ago that the decline in interest rates is due to increased saving.

“Yet, if “no one wants to borrow”, then rates would be going up, ceteris paribus, not down, no?”

Here you have lost the last vestige of sanity.

In what way?

(You also seem to have become French – perhaps not coincidentally.)

Snore.

29. October 2012 at 23:47

MF – do you seriously think that interest rates go up when the demand for loanable funds (borrowing) decreases? Do you also believe that the price of bonds rises when people sell more?

30. October 2012 at 05:40

Ritwik, I don’t agree that hyperinflations start with a Wicksell mistake. They are caused by printing too much money, using to monetize debts. I’m sure there are plenty of hyperinflations associated with positive ex ante real rates.

BTW, I do consider the fed funds rate to be a pure free market rate. There are no price controls. Yes, changes in the money supply can affect that rate, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a free market. The government buys copper, that doesn’t mean copper prices aren’t set in a free market.

30. October 2012 at 06:59

Criticize and mock the internet austrians if you like, but you have to admit that every true internet austrian has a strong respect for Frederic Bastiat and his classic deconstruction of the kenysian promoted broken window fallacy.

How many kenysians still to this day mindlessly repeat the great advantages to “economic growth” of bombing countries, breaking windows and hurricanes?

30. October 2012 at 07:38

Saturos:

MF – do you seriously think that interest rates go up when the demand for loanable funds (borrowing) decreases?

My theory of interest is somewhat complex, but the gist of it is that time preference is the anchor, and this, along with some accounting relations, ultimately manifests a difference between expenditures for goods, and expenditures for factors in the production of goods, i.e. nominal profits, and I hold that this profit constrains interest rates, i.e. determines them. This is the case even with a fixed money supply and volume of spending.

I made sure to include “ceteris paribus” when I made my initial argument, because when all else is held equal, I hold that a fall in borrowing will tend to widen the relative spread between the two expenditures listed above, because I assumed that the significant borrowing that takes place is for investment purposes, more so than for cosnumption purposes. Hence, when businesses borrow and invest less, then economic costs on income statements will fall. As alluded to, this will, ceteris paribus, widen the relative spread between aggregate revenues and aggregate costs. This will then tend to raise interest rates.

I do not subscribe to the loanable funds theory of interest. I can understand how what I said would throw you for a loop. Don’t worry about calling me insane, because when people are slightly riled up, their minds are a little more active, and that makes for better discourse, IMO. Not too riled up though.

Do you also believe that the price of bonds rises when people sell more?

ceteris paribus, yes, because this would bring about the same effects as above, only in the opposite directions. But things are rarely ceteris paribus. In this case, the rise in bonds could have come at the expense of equity, with no change to the key expenditure spread and thus no change in interest. But then again, the rise in bond sales could be associated with inflation, in which case we would be in a temporary environment where for now, what you call the liquidity effect would be dominant, and interest rates would fall. But if the inflation stops, that effect would end, and the addition to aggregate revenues would then make rates go up, but then because costs rise with a time lag, interest rates would then come back down.

30. October 2012 at 07:38

Or rates remain the same because the temporary inflation is foreseen.

30. October 2012 at 07:39

But the Kenysians are right, Gabe! Hurricane Sandy would cause a multiplier effect on output, boosting GDP by more than the cost of the repairs – provided the central bank was holding M0 constant.

Also, my pet peeve – “deconstruction”. You’re using it wrong.

30. October 2012 at 07:44

Gabe,

Bastiat’s broken window parable also applies to inflation, which is why Austrians, despite the seeming affinity with monetarists as against Keynesians, nevertheless rile the monetarists.

Inflation misleads people into believing they are wealthier than they really are, and it leads to capital consumption, not just via the taxation effect, but also in the ABCT malinvestment sense. This is analogous to breaking windows which then brings about effects that make it seem like prosperity is growing. After all, “production” does temporally increase.

30. October 2012 at 07:48

Inflation leads to a long term lower sloped wealth trajectory.

PS If you really want to rile Keynesians, and are willing to put aside any positive beliefs about inflation, then cite passages from Keynes’ essay “The Economic Consequences of the Peace”. There are so many anti-Keynesian arguments in that essay. Especially the one where he vehemently attacks inflation as the destroyer of civilization.

30. October 2012 at 09:09

Saturos is trolling right?

30. October 2012 at 22:51

Gabe, with a fixed money stock, people who received govt. expenditures would spend the receipts, creating more jobs…

Total expenditures of money equal the supply of money divided by the demand for holding it as a fraction of nominal income. Fiscal stimulus can work because it transfers money (literally money) from people sitting on it (which they do when interest rates are zero) to the government, who spends it instead of holding on to it. The total flow of money in the economy increases. Spending goes up. This creates jobs, when there are unemployed workers able to receive the spending.

(Unless there is perfect Ricardian equivalence, and people save enough to exactly offset future taxes. Then there’s only the initial spending, no multiplier. But that’s not realistic.)

OTOH if the central bank moves to offset the fiscal stimulus – then that’s a different story.

31. October 2012 at 05:42

saturo, The governemnt can’t give money to people without taking it from others.

When someone has money sitting in the bank it is because they don’t see a good enough opportunity to invest in. When the government or Fed decides to steal this money and spend it on facist cronyism(say blowing up brown people in far off lands)…then resources are re-directed away from other ventures and shifted towards the the facist/crony business of bombmaking. The potential of the “idle” money is decreased. Yes jobs are involved in the areas where money was redirected…but unseen jobs are taken away from more productive goals.

More destructively, the sturcture of the economy moves towards what is being rewarded(cronyism) over what a free-market rewards(helping your fellow humans through voluntary actions).

the advocates of blowing things up to improve the economy have a pecular fetish for spending money…as if “holding money” or saving as some call it does harm to the economy. Nothing could be further from the truth. When I decide to not bid up asset prices, more attractive investments become available.

31. October 2012 at 05:58

Gabe, you said,

“When someone has money sitting in the bank it is because they don’t see a good enough opportunity to invest in. When the government or Fed decides to steal this money and spend it […]then resources are re-directed away from other ventures”

You just contradicted yourself.

“When I decide to not bid up asset prices, more attractive investments become available.”