Confusing “history” with numbers

It turns out “Canucks Anonymous” is Adam P. Here he discusses the 1974 recession:

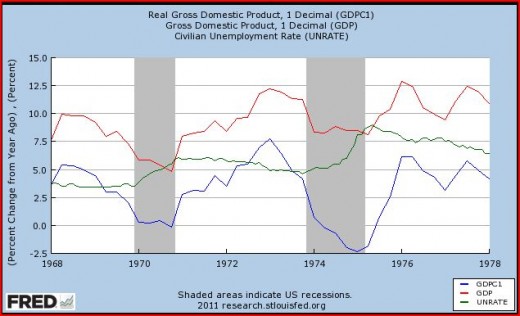

Below is a time series plot of real GDP growth, nominal GDP growth and the unemployment rate during the 1970s. On the eve of the supply shock NGDP growth is running about 10%, real GDP growth is running around 5% and unemployment is about 5%. Now, 10% NGDP growth is a higher level than you’d typically choose to target but the important thing to notice is that in the preceding 4 years or so the unemployment rate is extremely stable right around 5%, inflation is also very stable as both real GDP growth and NGDP growth are accelerating virtually in parallel. It certainly looks like an economy in equilibrium.

Now, when the shock hits real GDP growth of course plummets as is required for the episode to warrant the name “supply shock”, but look at NGDP growth, it is remarkably stable! This is exactly the response of monetary policy and NGDP growth that the market monetarists want, this is supposed to prevent unemployment from rising but if fails miserably! Unemployment rises sharply and remains elevated for several years.

Furthermore, as we all know there was subsequently an acceleration in inflation that got somewhat out of hand, you might even say an inflation overshoot perhaps?

This is an amazingly pure test case, NGDP did exactly as the market monetarists would want and the whole thing is a total failure. Monetary policy does not appeared to have fixed the situation.

I was somewhat in a state of shock after reading the preceding. It would be difficult to find a worse test of market monetarism in all of American history. Remember, we favor a stable 5% NGDP growth rate. Let’s examine all the flaws in Adam’s analysis:

1. NGDP growth rises sharply in the early 1970s, from barely over 5% to a peak of 12.5% in 1973. Then it falls to about 8% in the recession. Also recall that market monetarism is a natural rate model. That means even if NGDP growth had remained at 12.5% in 1974, and even if there had been no oil shock, we still would have expected a recession. The preceding demand-side growth certainly pushed unemployment below the natural rate, and hence a relapse was inevitable in 1974.

2. Now add on the fact that NGDP growth slowed by 450 basis points in 1974. If the decline had started from a 5% baseline, that would be like a decline to 0.5%.

3. Now add on the fact that there was a severe real shock to the economy, in the form of a dramatic reduction in OPEC oil production. Also recall that our economy was much more oil intensive back then. The easiest way to consider this case is to assume the AD curve is a hyperbola. Then if aggregate supply shifts left, we’ll have a recession, even with NGDP targeting.

4. Even worse, the data from this period was completely distorted by price controls. Economy-wide price controls were installed in 1971, and gradually phased out in 1973 and 1974. So the inflation and NGDP data for 1974 was biased upward by the removal of price controls. Money may well have been even tighter than it looked.

5. It’s also widely acknowledged that the natural rate of unemployment rose sharply during the 1970s—market monetarist policies have no control over that variable.

But even if you ignore price controls, and ignore the oil shock, and ignore the rise in the natural rate of unemployment, the recession of 1974 is roughly what a market monetarist would expect if the Fed revved up NGDP to get Nixon re-elected, and then slammed on the brakes in 1974.

To add insult to injury, Adam suggests that market monetarism is somehow to blame for the inflation overshoot of the late 1970s. Recall that NGDP grew at an 11% rate from 1972 to 1981. We recommend a 5% rate. Those extra six percentage points pushed inflation from 2% to 8%. There’s no mystery here, inflation rose because the Fed was ignoring the advice of market monetarists, and regular monetarists as well.

An amazing pure test case? I don’t think so. But if it was, market monetarism passed with flying colors. In my view it would be much more interesting to look at a period where NGDP growth was highly stable. Marcus Nunes had some great posts showing that when NGDP growth got more stable, so did RGDP growth.

Adam continues:

To conclude lets take a look at another historical episode. The following plot shows NGDP growth, real GDP growth, inflation and unemployment from 1957 to 1967 in the US. Inflation is extremely stable while real output growth varies a lot and thus NGDP growth is very volatile as well (both inflation and NGDP are included because the inflation series is ex food and energy).

Why would someone choose 1957-67? That’s the tail end of the Eisenhower/Kennedy low inflation period, and the first three years of the easy money policy that led to the Great Inflation? In addition, when NGDP growth slowed sharply (1957 and 1960) so did RGDP. So what’s that supposed to show?

Then one final shot at yours truly:

Unemployment stays stable around 5% the whole time. So, which outcome do you prefer?

Actually no. Unemployment rises to about 7% in the two recessions (when NGDP growth slowed sharply) and fell below the natural rate in 1966, as NGDP growth was excessively fast.

Scott Sumner says “I make no apologies for ignoring these little toy models, and having my policy analysis incorporate a complex mixture of politics, macroeconomic history, well-established basic economic principles, and logic.”

I pointed out here that “well-established basic economic principles” shouldn’t really be on that list, can we strike “macroeconomic history” as well.

If you are going to trash me for not knowing any “macroeconomic history” (history I lived through) you might want to read up and find out what actually happened to the US economy during the period you are discussing. History is more than numbers.

I don’t want to be too negative here. Adam did provide a useful public service. He showed that when NGDP growth slows sharply we usually get recessions.

Tags: 1970s

10. November 2011 at 17:51

An excellent rebuttal, albeit of a rather soft target. The fact that the 1970s period still makes people say stupid things (like attributing the rise in prices entirely to a cost-push-driven rise in the GDP deflator) shows that the main thing we can learn from history is that people tend not to learn from history.

I think a key point is that NGDP targeting doesn’t prevent all falls in real output. Among its virtues, however, is that it provides the best overall response to variations in real output, including supply-shocks like an oil crisis.

Provided a market monetarist understands that prices function as signals and a minimum of distortion is to be desired, they will obviously not want NGDP to be shooting up to almost 10% above RGDP. IIRC, velocity also becomes much more unstable at higher rates of GDP deflator growth, which is a practical reason for a market monetarist to want NGDP to be low (in relation to RGDP).

10. November 2011 at 17:56

What’s magical about 5%? Much of your thesis seems to revolve around avoiding nominal shocks. If NGDP is steady at 10%, then where is the “shock”? Actors drawing up contracts can do so with that trend growth rate in mind, so the higher NGDP growth rate would have no adverse redistributative effects.

If the i-word doesn’t matter, I don’t see what’s wrong with a high and stable NGDP growth rate. You might argue a high NGDP growth rate is inherently unstable, but I don’t know how you get there with out mentioning the i-word.

10. November 2011 at 18:08

And this post does a 3 country – 50 year span – generalization:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/11/08/%E2%80%9Cweaving-a-story%E2%80%9D/

10. November 2011 at 18:14

I’m befuddled at the nonsensical idea that demand-side policy is supposed to make the problems of a supply-side recession go away.

10. November 2011 at 18:16

Scott, I read the original CA post and agree with your rebuttal, but I think their were bigger mistakes in the CA post. Consider,

CA wrote: “The part that’s really interesting is the last bit that I’ve cited, “If those other prices, for example, wages, are sticky, then the effort to reduce the “welfare loss” from inflation causes a recession”. Bill is apparently claiming that under an NGDP target the recession would be avoided.”

CA is putting words into Bill’s mouth (whether accidentally or deliberately) to assert that NGDP targeters believe recession can be avoided in a supply shock. The argument as I read it is clearly that keeping inflation low in a supply shock creates *additional* welfare losses, since most contracts and prices are denominated nominally.

10. November 2011 at 18:56

Johnleemk:

I’m befuddled at the nonsensical idea that demand-side policy is supposed to make the problems of a supply-side recession go away.

The point of NGDP targeting is precisely to ignore supply side shocks. A strict inflation target, on the other hand, would be forced to respond to such shocks and thus apply “demand-side policy” to “supply-side recessions.”

10. November 2011 at 19:25

W. Peden, I agree.

David, You said;

“What’s magical about 5%? Much of your thesis seems to revolve around avoiding nominal shocks. If NGDP is steady at 10%, then where is the “shock”? Actors drawing up contracts can do so with that trend growth rate in mind, so the higher NGDP growth rate would have no adverse redistributative effects.

If the i-word doesn’t matter, I don’t see what’s wrong with a high and stable NGDP growth rate.”

I oppose higher NGDP growth because it leads to higher nominal interest rates, and thus higher taxes on capital. If we go to a consumption tax then I don’t see a big problem with 10%.

Of course we’ve never had stable 10% NGDP growth.

Marcus, Thanks for the link.

Johnleemk, I agree.

Steve, Yes, and I suppose it might also depend on the definition of recession. Output might fall, but not below its equilibrium level. I try to avoid those arguments, as they tend to end up being about semantics.

Anon1, I agree, and that’s what I thought Johnleemk meant.

10. November 2011 at 19:35

Yup, I wasn’t being sarcastic.

10. November 2011 at 22:02

You forgot about slapping this guy with the currency crisis in 1971; probably one of those things that get overlooked when one tries to prove an argument through omission. After all, he did accuse you of ignoring monetary history. One other interesting tidbit here, in this graph, is that unemployment never rose as high as it is now. The measurement of it is now more forgiving, and the rate started to come down as NGDP rose. The peak was not sustained, a far different story than what is taking place now where the Fed made no effort to maintain NGDP growth, or to give up more.

Further, I don’t remember you saying the current recession would never have happened, that unemployemnt wouldn’t have risen under NGDP targeting, or that it would be the silver bullet to make all our economic troubles disappear. What you did say was that this recession did not have to be as severe, unemployment would have have been as high or sustained, and that it would not have stuck with us for four years. None of those points is disproved by the data set here.

10. November 2011 at 22:09

Scott, don’t be lulled into a false sense of security. When you debate a Yankee Anonymous in January, you’re going to long for Adam P.’s kid-glove treatment.

10. November 2011 at 22:11

I had one of those moments where my fingers want to say something I didn’t intend. What I meant was that, in summary, you made these points about NGDP targeting:

The current recession did not have to be as severe as it has been

Unemployment would NOT have been as high or sustained

And that it wouldn’t have stuck around for four years with no end in sight.

10. November 2011 at 22:23

Evidently Adam P. needs a history lesson. Allow me to dig into my lecture notes (talking points).

Prior to the early 1970s most policy makers thought that 4% or 4.5% unemployment was a reasonable goal. The idea of a target for the unemployment rate largely grew out of hearings during the passage of The Full Employment Act of 1946. A popular book at the time, “Sixty Million Jobs” (1945) by Henry Wallace probably was responsible more than anything else for those specific figures. Well in any case, when Nixon entered office in January of 1969, the unemployment rate was 3.4%. An unemployment rate of 6% probably would have somewhat hindered his reelection chances in November of 1972.

During the 1960s most Keynesian economists believed in the concept of a fixed relationship between unemployment and inflation, or a Phillips Curve. But this relationship seemed to break down starting in the late 1960s. (The term “stagflation” was coined by British politician Iain Macleod in 1965.) This gave rise to the “accelerationist hypothesis” by Monetarists Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps, which essentially stated that any attempt to hold the unemployment rate below the “natural rate” would lead to accelerating inflation. They advocated a nonactivist approach to monetary policy believing that the unemployment rate would tend towards the natural rate without any intervention.

Then in 1975 Franco Modigliani and Lucas Papademos coined the term noninflationary rate of unemployment (NIRU) which was later revised to nonaccelerating rate of unemployment (NAIRU). While Friedman and Phelps believed that the existence of a natural rate implied that there was no useful trade-off between inflation and unemployment, Modigliani and Papademos interpreted the NAIRU as a constraint on the ability of policymakers to exploit a trade-off that remained both available and helpful in the short run. But despite the fundamental differences that still existed between the

Monetarists and the Keynesians, the NAIRU was seen by many contemporary economists as helping build a consensus about the nature of the inflation-unemployment relationship.

At first there was an attempt to estimate a fixed NAIRU for the United States that was valid for all time periods (usually estimated to be between 5.5% and 6.0%). By the late 1990s, as unemployment dropped well below that rate and yet inflation continued to be moderate, this idea was questioned. Now it is fairly well accepted that NAIRU varies over time. The CBO maintains a NAIRU data series that ranges from a high of 6.2% in the mid 1970s to a low of 4.8% since 2001.

So, to make a long story short:

1) We now know in retrospect that during much of this period NAIRU, the non accelerating inflation rate unemployment rate, was 6.0%-6.2%. Thus even at the worst point of the 1970 recession, unemployment was never actually above NAIRU.

2) Despite the fact that the economy was already at or above above potential output, and inflation was already moderately high (3%-6%), a loose monetary policy was run from early 1971 through late 1972. This was partly due to Nixon’s desire to get reelected in 1972 (the Federal Reserve was much less independent in those days).

3) As a result unemployment fell from a peak of 6.1% in August 1971 to a low of 4.6% in October 1973. In addition since unemployment fell below NAIRU during this period, year on year CPI surged from a low of 2.9% in August 1972 to a high of 12.2% in November of 1974.

Had we followed a policy of targeting a steady rate of NGDP growth during this period, unemployment would likely have remained much closer to NAIRU, and inflation would not have accelerated so dramatically, even given the supply side shock we endured at that time.

11. November 2011 at 01:21

It turns out “Canucks Anonymous” is Adam P? Scott, that name has been on all his blog-posts since his blog first appeared.

A more appropriate opening would be: “Careless reader that I am, it has just dawned on me that Canucks Anonymous is Adam P.”

11. November 2011 at 03:48

“History is more than numbers.”

I wish economists had the humility to accept that economics is more than numbers – or is that levers.

11. November 2011 at 05:07

Bonnie, That’s right.

Bob, I’m quaking in my boots.

Mark, Very good observations.

Kevin, Stupid me, I thought the word “anonymous” meant . . . anonymous.

Nevorp, Both.

11. November 2011 at 05:33

Mark: minor quibble. I don’t think Phelps was really a Monetarist. He just found that when he tried to model a Phillips curve theoretically, expected inflation kept appearing in the equation.

11. November 2011 at 05:38

“Recall that NGDP grew at an 11% rate from 1972 to 1981. We recommend a 5% rate.”

that’s a rather disingenuous comment. you recommend 5% *now*. it is impossible to say what you would have recommended had you been asked at the end of 1971. hindsight bias in action?

11. November 2011 at 05:46

MMJ, Your comment makes no sense at all. It’s Adam who’s trying to apply MM retroactively to the 1970s, not me. I’m just responding by pointing out that if you apply the proposal, it does well. Now no one would deny that if you had a version of MM with a higher trend NGDP growth rate, you’d have a higher inflation rate. But so what? How’s that an argument against MM? It makes no sense to me.

You could say the same about inflation targeting–what if the target were 8%?

11. November 2011 at 05:47

BTW, I was at Chicago during the 1970s, and favored low inflation even back then.

11. November 2011 at 05:54

off-topic, but it seems that comments on old posts don’t show up in “Recent Comments.”

Just wanted to say that I thought your interview with Kelly Evans was terrific.

11. November 2011 at 05:55

“I don’t want to be too negative here. Adam did provide a useful public service.”

Yes, that service would be to avoid his blog. I read the post and could only SMH at the number of poor interpretations of data and outright mistakes that he makes. The best advice for CA (and others) is to make sure you understand the fundamentals of the discussion before you try to challenge an opposing viewpoint.

11. November 2011 at 06:09

I am not going to comment on the substance of this argument, except to note Scott’s desperation in claiming that NGDP fell by 4.5% in 1974 (point 2). What I find amusing however, is the similarly between NGDP targeting and MMT disciples in how partisan and biased they become when their beliefs are challenged.

11. November 2011 at 08:16

Scott, typo?

“The easiest way to consider this case is to assume the AD curve is a hyperbola. ”

Shouldn’t that be the AS curve that is a parabola?

12. November 2011 at 12:01

Thanks Catherine, I don’t know about the comments.

Brian, Yes, I thought I was being generous.

Rebeleconomist. When someone ridicules me and can’t find any cogent arguments against my claims, that speaks volumes. I claim that even if NGDP growth had been 12.5% in 1974, MMs would have expected RGDP growth to slow. Do you have a problem with that? Adam doesn’t seem to understand it’s a natural rate model.

As far as the 4.5% drop; Adam said growth was constant, and I pointed out it fell. Who is correct?

TravisA, No, I meant AD is a constant level of P*Y.