Tyler Cowen responded to my recent post, arguing that China is a threat to the liberal world order:

If you are the global hegemon, and another country, largely hostile to your political values and geopolitical desires, engages in widespread subversion of your power and influence, you must in some way hit back. Otherwise you will not be global hegemon for much longer. And unlike India or the EU, China desires to build an international political and economic order which would destroy liberalism as we know it. Imagine a world where autocracy is a much more widespread norm, the Xinjiang detentions and North Korean nuclear weapons are considered entirely appropriate behavior, Taiwan is a vassal state, and few Asian countries could allow their media to print criticism of the Chinese government, for fear of retaliation. Institutions such as the WTO would persist only insofar as they created loopholes which gave China the benefits of membership without most of the obligations.

Did I mention that politics in Australia and New Zealand are subverted regularly and blatantly by Chinese influence and money? Very likely the same is underway in the United States (and other countries) right now.

You can put aside trade practices altogether, and simply look at the extreme and still under-reported degree of espionage and spying conducted by China, aimed at major U.S. corporations. It’s not quite an act of war, but it is not the classical model of trade either (“Mercantilism is bad…what’s wrong if they send us goods and we just send them back paper dollars?”). China is violating U.S. laws on a massive scale, and yes, I am sorry to say, trade is our main way of “reaching” them and sending a message.

First I’ll explain why I mostly don’t agree, and then I’ll also briefly describe how Tyler might be correct:

1. I don’t believe that China is trying to destroy the liberal world order. Here’s what I think they are actually trying to do. China accepts that the liberal world order will remain in place. The most developed countries will continue to be free market democracies. China likes to trade with those countries, and China respects their achievements. China doesn’t like or respect places like North Korea and Turkmenistan. Rather, China wants a free hand to continue being an authoritarian country, with a crackdown in places like Xinjiang. Unlike the Soviet Union, they are not trying to instill communism in other places. Their support for autocracies in the developing world is simply a marriage of convenience; they know that (in the UN) these countries will also oppose American attempts to force human rights on China. I believe that many Westerners wrongly apply the Soviet model, which doesn’t fit China at all. As an aside, Trump loves autocracies and views countries like Canada as enough of an enemy that we must stop buying their steel for national security reasons. (Of course, Tyler would not defend Trump on those points.)

2. The Xinjiang detentions are a gross human rights violation, but Trump is making no attempt to do anything about it.

3. China is probably unhappy with North Korea’s nukes, but doesn’t know what to do about it. Neither do we. Unlike the US, China also wants to avoid the collapse of North Korea, for geopolitical reasons. That’s the actual reason that China deserves criticism on North Korea; a collapse of their regime would be a good thing.

4. “Vassal state”? Taiwan is part of China. At least that’s the official view of Mainland China, the US, and the Taiwan constitution. According to international law, accepted by the US, regions like Taiwan, Crimea, Catalonia, etc., do not have the right to unilaterally secede, without permission from the central government. That doesn’t mean I oppose independence for certain regions—the Czech divorce seemed to work fine; I’m just describing the rules of the game. China is not claiming any inhabited land, anywhere in the world, that the US does not consider a part of China. China is not a Soviet style expansionist power, and for the past 2000 years has been the least expansionist great power in all of world history. They have 1.4 billion people at home to worry about; the last thing China wants to do is run other countries. Rather they like regimes who won’t criticize their human rights and are open to doing business with them.

5. I’m skeptical of Tyler’s argument that Asian media outlets are especially afraid to criticize China. The only one I read frequently is the SCMP, and it’s full of criticism of China (albeit perhaps less harsh than if China didn’t control Hong Kong.) How about the media in Japan? South Korea? Taiwan? India? I don’t doubt that a few pull their punches in order to have better business opportunities with China, but that’s their decision.

6. Like many developing countries, China is allowed more trade restrictions than the developed world. As China gets richer, it will adhere more closely to WTO rules. Indeed China has recently been reducing trade and investment barriers, and it’s in China’s interest to continue doing so.

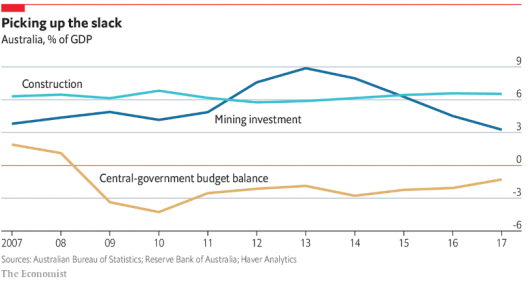

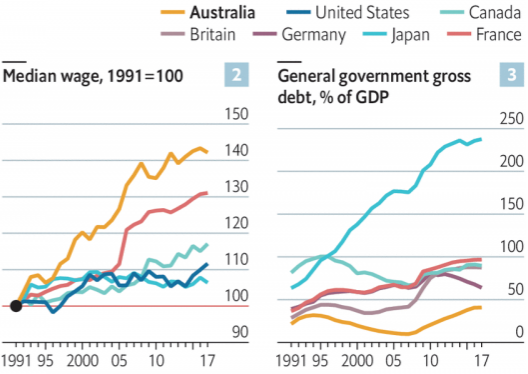

7. I follow Australian politics pretty closely, and I see no evidence that Chinese influence is a major problem. When cases of bribes are discovered, the politicians are punished. For those who have a more conspiratorial mindset than me, tell me why I shouldn’t regard Trump as Putin’s puppet? I’ve criticized Trump on that basis, but even I don’t think Russia controls the US to any significant extent. The Russia sanctions remain in place, even though Russia almost certainly has information that could be used to blackmail Trump, who appeared to lie about his business dealings there. That’s not to say that Australia isn’t a bit friendlier to China than it would be if a huge portion of its exports weren’t going there. But that influence does not require the bribery of local politicians, it’s economic self-interest. Australia just banned Huawei, over the objections of China (HT:Ray Lopez.)

8. This is hard to respond to:

You can put aside trade practices altogether, and simply look at the extreme and still under-reported degree of espionage and spying conducted by China, aimed at major U.S. corporations.

Like most bloggers, all I know is what I read. So if China’s doing all sorts of bad things that are not being adequately reported, I can’t comment. Nor can I comment on US espionage, something that I know little about. I’m certainly not going to defend espionage, but in this case I’d guess the actual damage from China stealing intellectual property (in global utility terms) is very small.

Tyler is very polite and often lets others have the last word, so let me try to take the other side of this issue for a moment, in case he doesn’t respond. Where might I be wrong? The best argument is that I myself am too much a product of the Cold War. I don’t see the China threat because I expect it to manifest itself in the way that the Soviets behaved after WWII; taking actual control of countries in places like Eastern Europe, or supporting guerrilla groups in the third world. Perhaps I’m missing that there is a new form of international competition, involving high tech espionage, fake news, bribing local politicians, economic support for friendly autocrats, etc. In other words, China’s doing a lot of the “softer” stuff the US did during the Cold War. That’s not a defense of China on my part, as the US was wrong to support autocrats and wrong to try to change foreign election results.

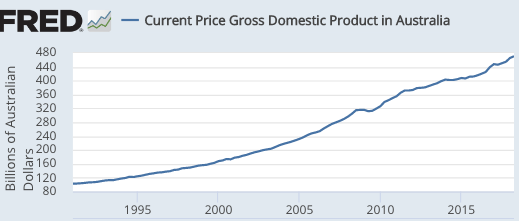

Here are a few final thoughts. Yes, the Soviet Union really was a nuclear threat, and we were lucky that there was no accidental escalation into outright war. But otherwise we Americans were wrong about the Soviets. Its collapse was pre-ordained by the relentless rise of neoliberalism after the 1970s, which continues to this very day. While I liked Reagan, in retrospect he had little to do with the collapse of Soviet communism. Similarly, we overestimate the threat posed by China, which is still poorer than Mexico. Unlike places like Mexico and Brazil, China has a strong desire to be a rich country, and will likely eventually become one. But it will only be able to do so by continuing to reform its economy.

If the US wants to continue to be a global hegemon, it’s most useful role is in enforcing the international norms against one country invading and taking territory from another country. (A norm China strongly supports!) And on that issue, there’s another great power that is a much greater threat than China. Like Tyler, I find NATO to be a very useful organization.

I also wonder if there is a sort of instinctive suspicion of powerful Asian economies, which don’t share our values in some respects. Trump has assigned Robert Lighthizer the responsibility of negotiating with China, despite that fact that he was one of those who warned about the Japanese threat during the 1980s, a threat now almost universally viewed as a false alarm. That doesn’t mean he’s wrong this time, but it should give us pause.

In any case, it’s all a moot point. Trump’s not skilled enough to win this game.