Today I’ll dissect a really sloppy article in The Telegraph:

To paraphrase Senator Everett Dirksen’s famous quote on the American military budget: a trillion here, a trillion there, and pretty soon you are talking about real money. Central banks may not have that much in common with the Army, but they are starting to fall into the same habit of spraying vast quantities of money at a problem, despite a troubling lack of evidence that it has any real impact.

Central banks don’t spend money in the fiscal sense; they create money and swap it for other assets.

So the ECB adopts a tight money policy in 2011 and the eurozone goes into recession. Draghi then switches to a slightly more expansionary policy in 2013 and the economy begins to recover. But because inflation is temporarily depressed by plunging imported oil prices, this somehow shows monetary policy is ineffective? I don’t get it.

Here in the UK, the Bank of England is meant to generate price rises of 2pc a year, but Chelsea FC are hitting the back of the net more frequently this season than the Bank hits its inflation target. Likewise in Japan and the US, central banks are consistently missing their official targets for inflation. What is going on?

So exactly how badly are the central banks missing their targets? By 10%? By 5%? By 1%? It does make a difference, no one expected perfection. After all, they were often 1% or 2% off during the Great Moderation.

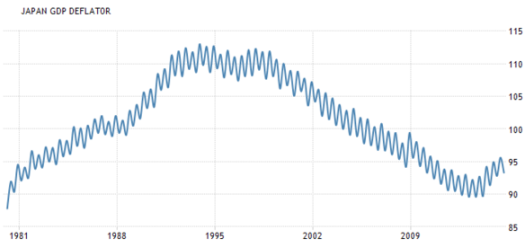

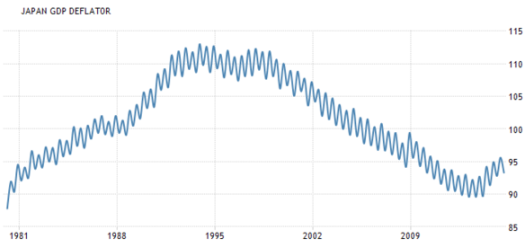

Up until 2013 the BOJ was not trying to create inflation. Then they adopted a 2% inflation target. Here’s what happened:

Over the past two years Japan has moved from a trend rate of 1% annual deflation to 2% annual inflation, using the GDP deflator. (I wish they’d give us seasonalized data.) That seems like a huge success to me. What am I missing?

Over the past two years Japan has moved from a trend rate of 1% annual deflation to 2% annual inflation, using the GDP deflator. (I wish they’d give us seasonalized data.) That seems like a huge success to me. What am I missing?

But what about unemployment? Oh yeah, that just fell to the lowest rate since the golden days of the early 1990s:

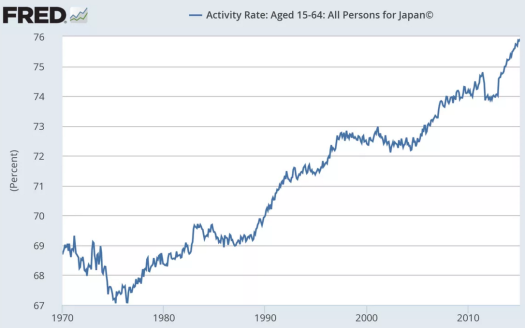

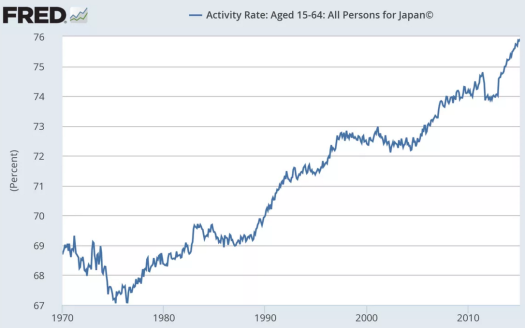

So they’ve hit their inflation target, and had huge success in lowering the unemployment rate. But isn’t that achieved by people exiting the labor force? Nope, just the opposite, Matt Yglesias recently pointed out that labor force participation in Japan is high and rising under Abenomics:

But what about the CPI? Yes, CPI inflation has been depressed recently by imported oil prices. That’s why the GDP deflator is a better indicator; it’s the price of domestically made goods matters for macroeconomic stability. (Obviously I’d prefer NGDP.)

But what about the CPI? Yes, CPI inflation has been depressed recently by imported oil prices. That’s why the GDP deflator is a better indicator; it’s the price of domestically made goods matters for macroeconomic stability. (Obviously I’d prefer NGDP.)

So Japan’s hit almost exactly 2% inflation on Japanese produced goods and services, after decades of steady 1% deflation. Unemployment has fallen to a multi-decade low. Labor force participation is soaring. And yet we are to believe that Abenomics has failed solely because Japanese motorists are suffering from dramatically cheaper imported oil, and as a result Japanese real wages are rising strongly? This stuff is so silly I couldn’t make it up if I tried. Whenever I read someone suggest that Abenomics has failed I immediately write them off as non-serious.

I was wrong about Abenomics. I thought the monetary “arrow” would be a modest success, as they were on the right track but not doing enough. In fact, so far the monetary arrow has been an overwhelming success, beyond almost anyone’s wildest dreams. (The other two arrows are still in the quiver.) I’m still expecting closer to 1% inflation over the next few years, but even that would be a huge success compared to recent decades.

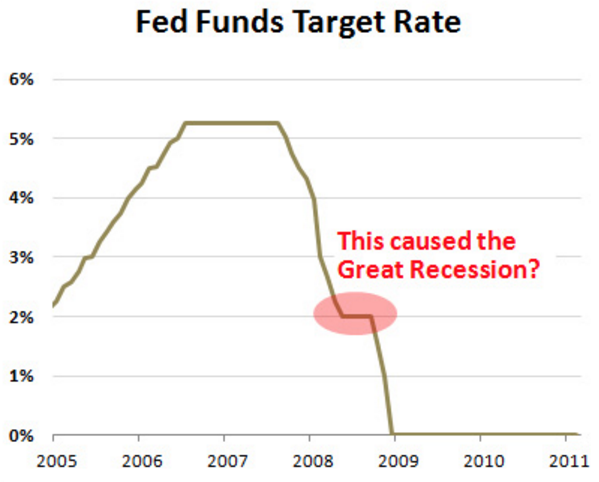

But how about the US? Haven’t we fallen short of 2%? Yes, but the Fed is about to raise interest rates next week precisely because they think inflation is only temporarily depressed by falling oil prices, and that we are on track to 2% inflation when that shock passes. (Yes, oil prices are still falling, but surely they can’t fall below zero.)

I suspect the Fed is too optimistic, but this has nothing to do with the impotence of monetary policy. Even economists who think QE is 100% ineffective concede the Fed could choose to not raise interest rates in December, and that this would lead to higher inflation. You might not like Fed policy, but the Fed believes inflation is right on track to being on target in a couple years. I thought the silly blather about monetary policy ineffectiveness would stop once the Fed raised rates, but that doesn’t seem to be the case.

A new paper by the Bruegel Institute argues that central banks have lost their ability to control inflation. At the moment, that doesn’t matter very much, because prices are generally stable. But (and it’s a big “but”) if we can’t control inflation on the way down – and it appears we can’t – what makes us think we can control it on the way up? Once prices do finally tick up, it may turn out to be impossible to stop them. And that is worrying.

By now it should be clear to everyone that the ability of central banks to control inflation has disappeared. Take the eurozone to start with. The ECB has an official target of prices rising by 2pc a year.

Clear to everyone? First one needs to present some evidence, and the author fails to do so. He also gets the ECB’s inflation target wrong; it’s not 2%, it’s “below but close to 2%”. Yes, the inflation rate is further below 2% than they’d like, but that partly due to the recent plunge in oil prices. And why would central banks be unable to prevent rising inflation? None of the theories that I know of that predict monetary policy impotence at the zero bound have any implication for preventing a rise in inflation.

Then again, it may be something more serious. In a recent paper for the Bruegel Institute, Gregory Claeys and Guntram Woolfe argue that central banks may have lost their ability to control inflation. They point out that globalisation and new technologies have already been shown to have had a powerful disinflationary impact right around the world: “The important question is whether these integration trends affect the transmission mechanisms of monetary policy and reduce the ability of central banks to fulfill their mandate.”

This isn’t just wrong, it’s doubly wrong. Positive supply shocks don’t prevent central banks from hitting their inflation target. Not in monetarist models. Not in New Keynesian models. Not in Austrian models. Not in any plausible fiat money model. Even worse, to the extent that positive supply shocks hold down inflation, they do so by boosting output growth. But growth has also been unusually low in recent years, not just in the US, but also globally. Fast rising productivity due to globalization is the least of the world’s problems.

PS. I have a post on Krugman/Cruz over at Econlog.

HT: Caroline Baum