Joan Robinson wins

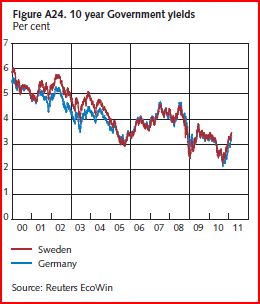

Has there ever been a more complete intellectual breakdown in our profession? Economists of both the left and the right have been disdainful of the idea that the Fed and ECB adopted ultra-tight monetary policy in late 2008. When I ask economists why, they often point to the low nominal interest rates. When I point out that for many decades nominal interest rates have been regarded as an exceedingly unreliable indicator of monetary policy, they shrug their shoulders and say “OK, then real interest rates.” At that point I explain that real interest rates are also an unreliable indicator, but if you want to use them it’s worth noting that between July and late November 2008, real rates on 5 year TIPS rose at one of the fastest rates in US history, from just over 0.5% to over 4%. Then they point to all the “money” the Fed has injected into the system (actually interest-bearing reserves.) I respond that the people who pay attention to money (the monetarists) don’t regard the base as the right indicator, as it also rose sharply in 1930-33.

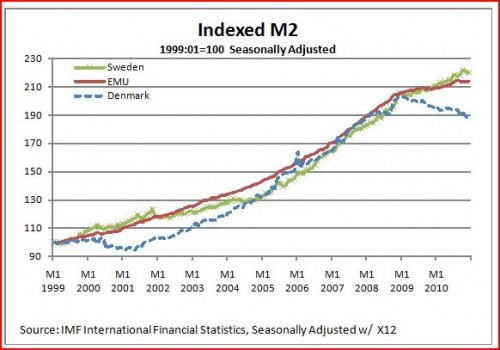

Their best argument has been “OK, but M2 fell sharply in the Great Depression, and M2 has risen briskly in this crisis.” At that point I am usually stumped, and merely remind people that the profession no longer paid attention to M2 after the early 1980s, regarding it as “unreliable.” But now I have a better answer. I was reading a post by Justin Irving and came across this very interesting graph:

At first glance it doesn’t look like much of interest has happened to the eurozone money supply. But remember that growth tends to be exponential, and so please visually follow the red euro M2 line upward. Notice the break in growth in 2008. Where would the money supply be if the ECB had maintained steady eurozone M2 growth? Justin also supplied me with the actual seasonally adjusted data. Here are some data points:

Date M2 growth from 27 months earlier

April 2004 5339999 14.9%

July 2006 6372397 19.3%

October 2008 8014245 25.8%

January 2011 8413040 5.0%

So after rising at fairly rapid rates for years, M2 growth slows to barely over 2% annual rate over the past 27 months. What would Milton Friedman say about that?

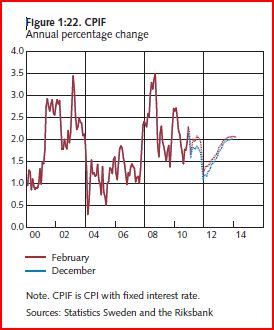

If pressed, Keynesians will usually point to real interest rates as the right measure of monetary ease or tightness. By that criterion the Fed adopted an ultra-tight monetary policy in late 2008. Monetarists will usually say that M2 is the best criteria for the stance of monetary policy. By that criterion the ECB adopted an ultra-tight monetary policy in late 2008. And yet it’s difficult to find a single prominent macroeconomist (Keynesian or monetarist) who has publicly called either Fed or ECB policy ultra-tight in recent years. Maybe tight relative to what is needed, but not simply “tight.”

I’m calling out my profession. Do they really believe what they claim to believe about good and bad indicators of monetary tightness? Or in a crisis do they atavistically revert to the crudest measure of all, nominal rates. Joan Robinson is famous for once having argued that easy money couldn’t possibly have caused the German hyperinflation, after all, nominal interest rates in Germany were not low during 1920-23. Have we advanced at all beyond Joan Robinson in the 73 years since she made that infamous remark? I used to think the answer was yes; now I’m not so sure.

[BTW, modern monetarists like Michael Belongia and William Barnett advocate use of a divisia index for money. I saw a paper by Josh Hendrickson that showed by that measure money became very tight in the US during 2008.]

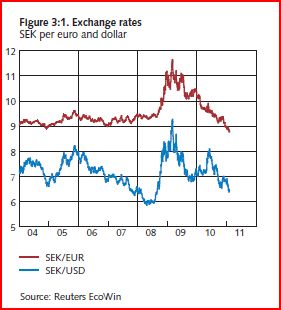

Justin’s post also contains another interesting idea. Notice how much more slowly Danish M2 grew as compared to Swedish, or even eurozone M2. Sweden has a floating exchange rate and devalued sharply in late 2008, Denmark’s currency is fixed to the euro, and Denmark’s economy is much weaker than Sweden’s (in terms of NGDP and RGDP growth.) Here’s Justin:

I am examining this issue in my Masters Thesis and it just occurred to me that it might be interesting to see how Denmark and the ECB compare to Sweden on Milton Friedman’s favored measure of monetary policy-M2 growth. M2 is a standard measure of how much money there is in the banking system of an economy. It is beyond the point of this post, but there is good reason to think that if M2 drops precipitously, that spending will fall and that the economy will grow below its potential. Unfortunately we cannot see M2 for Finland alone as there is no real way of distinguishing between the stock of Euros within the Finnish economy, and those in the broader world. The Danish crown however is something like that radioactive dye physicians inject into peoples veins so that they can see the circulatory system on an x ray. The Danish currency is essentially the Euro, except that we can track it by the fact that it has pictures of Viking longships on it if it is currency, or a DKK currency ID next to it if it is electronic money.

Because Denmark fixes the price of the Danish Crown in terms of Euro, the central bank is constrained in how it can stabilize M2. Central banking is, at the end of the day, pretty simple (no to be confused with easy). The only thing the bank can really do is change the quantity of money and see how the market reacts. Most of the time, central banks pick an interest rate they think appropriate and print money or pull it from circulation (by selling financial assets or foreign currency they have accumulated) until the interest rates moves where they want it. When interest rates fall to zero, central banks need to pick other variables to guide their money printing decisions, such as stocks, exchange rates, consumer prices or nominal GDP. In the case of Denmark, the central bank targets the exchange rate against the Euro by buying and selling the Danish crown in currency markets so that its rate against the Euro never changes. As Denmark is an open economy with free capital flow, this means that they have essentially no control over their monetary policy. Danish interest rates and money supply have to adjust to whatever is necessary to keep the Euro rate stable.

I love Justin’s radioactive dye analogy; it reminded me of something I noticed in the Great Depression. In the US the monetary base fell 7% between October 1929 and October 1930, under the Fed’s tight money policy. Then it rose substantially after October 1930. But money didn’t become easier, rather the Fed was partially accommodating the hoarding of cash and reserves during banking panics. But not fully accommodating the demand, as NGDP continued falling sharply after October 1930. How could we know if this explanation is correct? One answer would be to look for a similar economy, without banking panics. In Canada there were no bank panics, and cash in circulation continued falling throughout 1929-32, if my memory is correct. Because the US deflation was transferred to Canada via the international gold standard, they had no choice but to deflate their own currency. Canada in the early 1930s is like Denmark in the past three years.

There’s an old fairy tale where a beautiful princess looks in the mirror and sees her true self, which looks more like an ugly witch. The US monetary policy looked beautiful in the early 1930s, if one just focused on the base. But all one had to do was look to the north to see just how ugly it really was. If the ECB wants to take a look in the mirror, I suggest they take a look at the contrast between Swedish and Danish M2 growth. The Danish policy it what their policy really looks like. It’s not a pretty sight.

BTW, Justin’s blog post is more valuable than most master’s theses that I have seen.

PS. I believe Canada may have done a small devaluation in late 1931, but not enough to prevent deflation.