NeoFisherism in Turkey

From the FT:

The Turkish lira led a broad drop in emerging market currencies on Tuesday after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed to take greater control of monetary policy if he wins elections next month.

Mr Erdogan has for years harboured a deep antagonism towards high interest rates, taking the unconventional view that they cause rather than curb inflation. Last week, he warned that they were “the mother and father of all evil”, fuelling concern that he would not allow the central bank the freedom to raise rates.

The Turkish president told Bloomberg that cutting interest rates would lower inflation. “The lower the interest rate is, the lower inflation will be,” he said. “The moment we take it down to a low level, what will happen to the cost inputs? That too will go down . . . you will be able to get the opportunity to sell your products at much lower prices . . . The matter is as simple as this.”

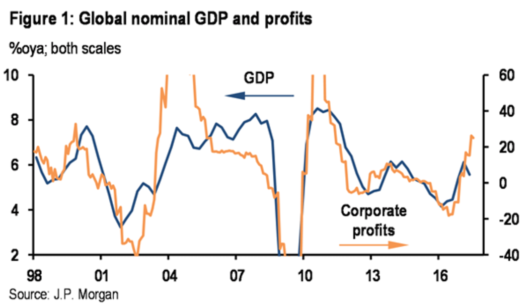

PS. A new paper by Warwick J. McKibbin and Augustus J. Panton makes the case for NGDP targeting:

Looking to the future the importance of supply shocks being driven by climate policy, climate shocks and other productivity shocks generated by technological disruption as well as a structural transformation of the global economy appear likely to be increasingly important. This suggests an important evolution of the monetary framework may be to shift from the current flexible inflation targeting regime to a more explicit nominal income growth targeting framework. The key research questions that need further analysis are: how forecastable is nominal income growth relative to inflation?; and what precise definition of nominal income is most appropriate given the ultimate objectives of policy (nominal GDP, nominal GNP or some other measure that is available at high frequency (e.g. big data on spending)). Also, the issue of growth of income versus the level of income is an open research question with many of the same issues to be faced as the choice between inflation targeting versus price level targeting.