1. For a guy who has been right about everything, Paul Krugman sure is wrong about an awful lot of things. Bob Murphy has an excellent new post which digs up lots of Krugman claims that turned out to be somewhat less then correct.

Krugman, armed with his Keynesian model, came into the Great Recession thinking that (a) nominal interest rates can’t go below 0 percent, (b) total government spending reductions in the United States amid a weak recovery would lead to a double dip, and (c) persistently high unemployment would go hand in hand with accelerating price deflation. Because of these macroeconomic views, Krugman recommended aggressive federal deficit spending.

As things turned out, Krugman was wrong on each of the above points: we learned (and this surprised me, too) that nominal rates could go persistently negative, that the US budget “austerity” from 2011 onward coincided with a strengthening recovery, and that consumer prices rose modestly even as unemployment remained high. Krugman was wrong on all of these points, and yet his policy recommendations didn’t budge an iota over the years.

Far from changing his policy conclusions in light of his model’s botched predictions, Krugman kept running victory laps, claiming his model had been “right about everything.” He further speculated that the only explanation for his opponents’ unwillingness to concede defeat was that they were evil or stupid.

Read the whole thing.

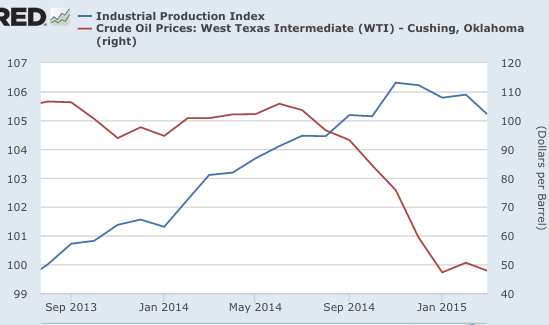

2. Caroline Baum has a very nice post on “never reason from a price change.” She’s one of the relatively small number of journalists that seem to really get this idea.

The Fed is equally confused when it comes to long-term rates. If you were to ask policy makers if interest rates move pro-cyclically, they would all answer yes. But when rising market rates become a reality, the cries go out that higher rates will damage the economic growth. At the same time, a decline in long rates is automatically assumed to provide economic stimulus. Alas, the expectation that the 100-basis-point decline in 10-year Treasury yields last year would boost investment was mugged by reality.

Getting back to oil prices, economists are still waiting (hoping?) for the oil-price-tax-cut to materialize. Bad weather is getting old as an excuse.

Read the whole thing. Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous:

3. John Tamny has a post entitled:

Baltimore’s Plight Reveals the Comical Absurdity of ‘Market Monetarism’

In case you are wondering who John Tamny is, in an earlier post he explained that Bernanke’s inflation targeting idea was unwise, as it would imply that each and every price was stable, not just the overall price level. Flat panel TV prices could no longer decline.

I’m too busy to do a post mocking all of Tamny’s more recent claims, but he was polite enough to write it in such a way that all I really need to do is quote him. It’s self-mocking:

‘Market monetarists’ believe that economic growth can be managed by the Federal Reserve. . . .

Market monetarists’ believe the Fed can achieve the alleged nirvana that is planned GDP growth and national income through money supply targets set for the central bank by members of the right who’ve caught the central planning bug. . . .

In fairness to the neo-monetarists, they would all agree that Baltimore has problems that extend well beyond money supply. Still, if money supply planning is the alleged fix for the broad U.S. economy, presumably it would have a positive impact locally. . . .

Specifically, ‘market monetarists’ seek consistent money supply growth, and then when the economy is weak, a bigger increase in the supply of money to boost GDP. . . .

It’s kind of simple. Money supply once again can’t be forced. . . .

It can’t be repeated enough that production is money demand, and is thus the driver of money supply. Money supply shrank in the 1930s not because the Fed decreased it (if it had, alternative sources of money would have quickly revealed themselves), but because the federal government erected massive tax, regulatory, and trade barriers to production. All that, plus FDR’s devaluation of the dollar from 1/20th of an ounce of gold to 1/35th of an ounce in 1933 further put a damper on the very investment that powers new production. It’s forgotten by economists today, but when investors invest they’re tautologically buying future dollar income streams.

If you are looking for a few laughs, the Tamny piece is highly recommended. Indeed I’d call it “tautologically funny.”

PS. Over at Econlog I have a new post that indirectly addresses some of the confusion in the Tamny post.

HT: David Beckworth

Update: Well I may not have gotten the ECB to adopt NGDPLT, but consider this comment from yesterday’s post:

Must be nice to be the sort of rich hedge fund manager that gets this “critical” information before the rest of us.

And from today’s WSJ:

The ECB will post speeches of its board members on its website when they are scheduled to begin, without making them available to journalists ahead of time under embargo as the ECB had done for many years.

The decision, which takes effect immediately, came one day after the public release of comments by executive board member Benoit Coeuré caused a stir in financial markets. Mr. Coeuré said the ECB would front load bond purchases under its €1.1 trillion ($1.2 trillion) quantitative easing program in May and June to account for a summer lull in bond markets.

HT: lysseas