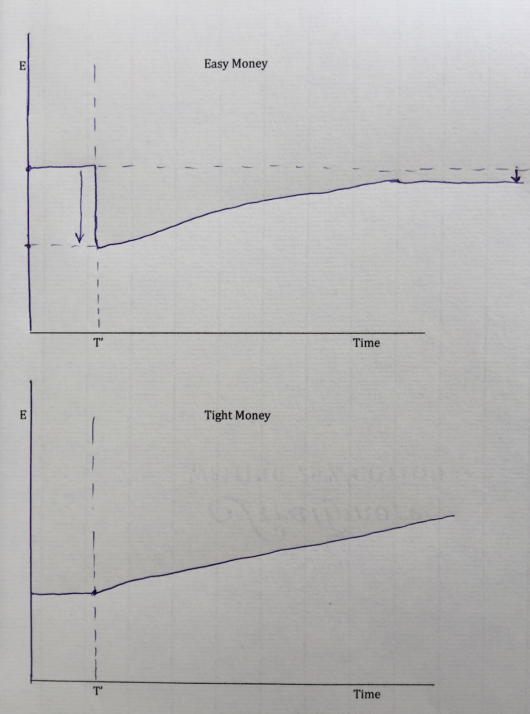

Two examples of low interest rate monetary policies

I’ve done a number of posts comparing New Keynesian and NeoFisherian views on the relationship between monetary policy and interest rates. Here I’d like to illustrate the problem with a picture, as people often have trouble understanding this issue. It’s really hard to not reason from a price change. It’s hard to stop thinking of interest rate movements as a “policy” rather than an outcome.

These two graphs show the path of the exchange rate (E) over time, under two different monetary policies. In both cases a higher exchange rate (E rising) reflects domestic currency appreciation. Importantly, both of these examples are “low interest rate policies”, when the central bank reduces interest rates to a lower level than before. But case #1 is an easy money policy, whereas case #2 is a tight money policy:

To focus on the essentials, I’d like to assume that a policy change occurs at time = T’, and that the following movement in the exchange rate is anticipated, once policy has shifted. (The policy move itself was unanticipated beforehand.)

Notice that in both cases, the exchange rate is expected to appreciate after time = T’. Because of the interest parity theory, this expected appreciation means that interest rates will be lower than before the policy change, when the exchange rate was stable and interest rates were the same as in the other country. So from the interest parity theory we know that these two cases are both shifts to a lower interest rate policy.

But now let’s look at the long run impact of the two policies on the level of the exchange rate. In case #1, the exchange rate ends up lower (depreciated) in the long run, despite the near-term expectation of appreciation. Because of PPP, that means the policy is expected to increase the price level in the long run. In other words, it’s an expansionary monetary policy.

In case #2, the exchange rate appreciates in the long run, yielding a lower price level. That’s a contractionary policy.

Because the first case looks so convoluted—a currency that is expected to appreciate over time but still end up lower than before—you might think it represents the “weird and controversial model”. Just the opposite, the first case is the New Keynesian model of easy money, and more specifically the Dornbusch overshooting version. The second more straightforward case reflects the weird and controversial NeoFisherian model. Just looking at the second graph, it’s easy to see how the NeoFisherians are able to get their result from mainstream mathematical models of the economy.

Here’s another way of thinking about the two cases. In case #1, there is a one-time increase in the money supply (and/or reduction in money demand). It reduces interest rates (due to the liquidity effect.) But it also leads to expectations of a higher price level in the long run, due to currency depreciation and PPP. Because prices are sticky in the short run, the effect of easy money is to initially depreciate the currency, not raise the price level in proportion.

In case #2, there is a permanent decrease in the growth rate of the money supply (and/or increase in money demand growth). Because of the quantity theory of money, that leads to a permanent decrease in the inflation rate. And because of the Fisher effect, the lower inflation leads to lower nominal interest rates. And because of interest parity, lower nominal interest rates lead to an expected appreciation in the currency. But you don’t even need the interest parity relationship. By itself, the lower expected inflation combined with PPP leads to the expected appreciation in the currency.

So how does this help us to better understand the New Keynesian/NeoFisherian dispute? It may be helpful to contrast the “highly visible” with the “highly important”. The New Keynesians are focused on the highly visible, while the NeoFisherians are focused on the highly important.

The vast majority of specific, short-term decisions by central banks are better viewed as one-time shifts in the money supply, rather than permanent changes in the growth rate of the money supply. Thus “easy money” announcements often make short-term interest rates fall, even as inflation expectations rise. At the same time, the truly major moves in interest rates over time largely reflect longer-term changes in the growth rate of the money supply (and money demand—in more recent years). Thus the low nominal rates in Japan are primarily due to tight money, not easy money.

Both the New Keynesian and the NeoFisherian models are wrong, as both sides engage in reasoning from a price change. The correct (market monetarist) model says that low rates can reflect easy or tight money, and that one should not draw any inferences about the current stance of monetary policy by looking at interest rates.

If one cannot draw any inferences about the current stance of policy by looking at rates, can one draw any inferences at all? I see two:

1. On any given day, a decision by a central bank to cut rates by more than the market expected is usually (not always) expansionary. It reflects “expansionary intent” and may be viewed as a signal by the central bank of a desire to make policy more expansionary. This is, of course, consistent with New Keynesianism. But it does not mean the current stance of policy is expansionary.

2. When nominal interest rates fall persistently over a long period of time, it is usually (not always) evidence that monetary policy has been contractionary. (This is more consistent with NeoFisherism). But it does not mean that the current stance of monetary policy is contractionary. As usual, Milton Friedman was decades ahead of the rest of the profession:

Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy. . . .

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.

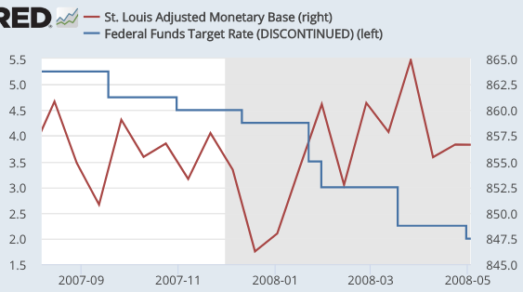

In America, monetary policy in 2017 and 2018 became a bit more expansionary, despite higher rates.