Since the election, there’s been a lot of speculation that we are transitioning to a more inflationary environment. That’s certainly possible, but I’d encourage everyone to take a deep breath. There are three arguments I’ve seen for this claim, and two are extremely weak, while the third is mixed. Let me start with the strongest of the three, rising TIPS spreads.

As a believe in the EMH, I am not going to discount the importance of TIPS spreads, I’ve cited them in the past. Rather, I’d like to put that evidence in perspective with a few observations:

1. As of today, 5 and 10 year T-bond yields are up 50 and 54 basis points from a month ago. That’s pretty significant. But that’s mostly real rates, which are up 32 and 33 basis points. That means TIPS spreads are up 18 to 21 basis points. That’s not trivial, but it’s also not a dramatic game changer. We’ve seen similar moves at times over the past 5 years, and not much happened.

2. In addition, the level of inflation expectations remains well under 2%, especially when you subtract 30 basis points to reflect the fact that PCE inflation (the Fed’s target) runs about that much below CPI inflation (reflected in TIPS.) This is important, because TIPS spreads (as we’ll see) are basically the ONLY evidence we have for the inflation story. And even they are not predicting that the Fed will abandon its 2% inflation target (or ceiling, as some of you would claim.)

3. While I often cite TIPS spreads, I’ve also acknowledged in the past that experts believe these spreads are somewhat distorted by shifts in risk premia. They aren’t perfect. The Cleveland Fed, among others, attempts to come up with adjusted spreads to better reflect true inflation expectations. Of course these estimates are model based, and hence are not perfect either. Please send me any recent ones you come across.

Update: JP Koning directed me to the Cleveland Fed. Their model adjusts TIPS spreads to account for risk premia. Yesterday they updated their 10-year inflation expectations estiamtes to 1.75%. Last month it was 1.69%, and two months ago it was 1.72%.

4. With some uncertainty about the accuracy of small moves in the TIPS spreads, where else can we look for inflation signals? Well, the big story since the election has been the dramatic appreciation of the US dollar. If we are to believe that Trump plans to debase the dollar through higher inflation, would you expect the forex value of the dollar to be surging higher on that information? That’s not the macroeconomics I studied in school. Indeed doesn’t the recent upswing in the dollar suggest we might get a bit lower inflation, as import prices drop?

5. In contrast, there is an alternative explanation for these events. Maybe the markets expect a dose of supply-side Reaganomics, and this is driving up expected RGDP growth (modestly to be sure, as rates are still low in absolute terms) and also driving up real bond yields and the value of the dollar. That makes more sense than the inflation story, although I’m also willing to accept a mixed claim of “0.3% more trend RGDP growth and 0.2% more inflation” as being consistent with the various markets.

The other two arguments cited for higher inflation are especially weak. One claim is that fiscal stimulus will drive up inflation. But Yellen recently shot that down—the Fed fully intends to do monetary offset, and is recommending that Trump not do fiscal stimulus. I have a post on that at Econlog. (BTW, people frustrated with my Trump derangement over here should keep in mind that I always try to put my most important posts at Econlog.)

The other reason cited is that Trump might pack the Fed with compliant pro-growth, low interest rates doves like Arthur Burns. But there are many problems with that claim. Trump would not be able to get a change in the Fed’s official mandate through the Senate. It would be highly controversial, and there are more than enough GOP mavericks and inflation hawks in the Senate to stop it. Ditto for a choice of an obvious lackey for chair of the Fed. He needs to put up a respectable name. The press has discussed two groups of possible Fed appointments. One is traditional conservatives like John Taylor and Martin Feldstein. And the other group is more heterodox thinkers like David Malpass and Judy Shelton. Neither group includes a single person who can be described as a “dove”. Does anyone seriously think that John Taylor would switch the Fed to a 4% inflation target just to please Trump?

For better or worse we are locked into a world of low inflation. Get used to it, it’s not going away. And that means that artificial attempts to generate higher wages will do nothing but slow growth and reduce employment.

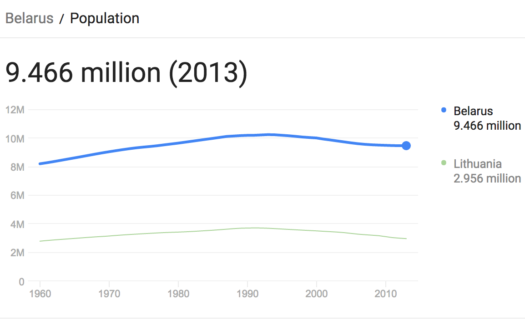

And yet Belarus has lots of inflation:

And yet Belarus has lots of inflation: Not as bad as the 100% inflation of 2012, but still running around 10% per year in recent years, despite a falling population.

Not as bad as the 100% inflation of 2012, but still running around 10% per year in recent years, despite a falling population.