Caroline Baum has an interesting article on a new book written by DiMartino Booth, who worked at the Fed from 2006 to (I think) 2015:

The Fed regularly publishes a summary of economic conditions in the 12 federal reserve districts, but when real-world information contradicts the Fed’s econometric model, the model wins. DiMartino Booth provided Fisher with real-time information — not seasonally adjusted, to the consternation of the staff — gleaned from an array of market sources and data sets.

Fisher, with his background in business, finance and government, earned a reputation as a maverick inside the Fed. He dissented from the FOMC statement five times in 2008, twice in 2011 and twice again in 2014, in all cases favoring less monetary accommodation or earlier rate hikes than the consensus view.

Fisher retired at the end of 2014; DiMartino Booth followed shortly after, once she realized her real “mission” is to educate the public about the inner workings of the Fed. “Fed Up” succeeds in doing just that. . . .

One of her suggestions made me laugh out loud. The Fed should ship the Ph.D. economists back to academia and use the money saved to hire some crack bank supervisors at competitive salaries for the Fed’s “Sup & Reg departments,” traditionally a second-tier job at the Fed.

A few comments:

1. In retrospect, it’s clear that all of the Fisher votes cited above were in error. Indeed in my view that’s not even debatable. The fact that it is debated tells us that we need to reform Fed policy is such a way that clearly mistaken votes are no longer debatable. Chad Reese and I have a letter just published in The Hill that discusses this issue.

2. You generally don’t want to rely on non-seasonally adjusted data, which might signal a huge “boom” in December.

3. Over the past three decades, the Fed has relied far more heavily on academic economists than in the past. During this period, Fed policy has become vastly more stable than in the prior 70 years, whether you rely on inflation or NGDP growth as your indicator.

The author advocates greater diversity at the Fed: specifically, more staffers with actual business experience and fewer ivory-tower types. She would like to see an increased focus on systemic risk. And she wants Congress to release the Fed from its dual mandate — stable prices and maximum employment — so it can focus solely on price stability. . . .

Where I [Caroline Baum] would challenge DiMartino Booth is on her recommendation that the Fed normalize the overnight rate and pledge never to breach the 2% floor again so as not to punish savers.

I have not read her book and I may be misinterpreting the comment about a 2% floor. But if the floor refers to interest rates, then I’d say the proposal is either absolutely horrible or mindbogglingly insane. Let’s start with the best case, absolutely horrible:

1. One way to make sure interest rates never again fell below 2% is to raise the inflation target to 10%. That’s a horrible idea, and since it would probably punish savers I don’t think that’s what the quote refers to.

2. If the inflation target is kept at 2%, then a 2% interest rate floor would be non-credible, because it would be impossible for the Fed to achieve. But trying to achieve it could easily cause another Great Depression. A mindbogglingly bad idea. This is why you don’t want non-PhDs making monetary policy. Indeed, even the brief April to October 2008 2% interest rate floor proved to be disastrous.

PS. Vaidas Urba sent me another post that comments on the same book. Looks like a very good blog.

PPS. The case for the Fed increasing its interest rate target is growing stronger by the day. Some of the new data looks quite strong for both prices and output. Continued talk of fiscal stimulus is starting to look kind of silly. For the first time since I started blogging, I see the monetary policy risks as being balanced, instead of skewed to the downside.

PPPS. Many commenters are unaware of my current views on NGDP targeting. I currently favor the “guardrails” approach, which is not susceptible to the market manipulation problem. Nor would lack of trading be a problem. My attempt to create a small NGDP prediction market is not to be confused with this policy proposal. I have a new article in the Journal of Macroeconomics that explains my current views on a wide range of monetary policy rule issues.

PPPPS. A zero percent interest rate floor would be less bad than 2%, as the Fed has the option of QE.

PPPPPS. For those who don’t have access to the JM article, the basic idea is as follows. The Fed sets a 4% NGDP target path, level targeting. If the economy is currently on target, the Fed commits to take a short position against any NGDP futures trader going long at 5% NGDP growth, and the Fed takes a long position on any NGDP futures traders who go short at 3% NGDP growth. Thus the Fed might be exposed to loses if the actual NGDP growth rate is outside the 3% to 5% guardrails. The losses could be large if, ex ante, it’s clear to traders that NGDP growth will be far too high, or too low.

The Fed monitors the trades. It still has 100% discretion over monetary policy, with the proviso that it be willing to commit to the NGDP positions described above. This is much like Bretton Woods or a gold standard (where they committed to exchange money for gold, instead of NGDP contracts), and no more susceptible to market manipulation than those regimes. Indeed less so, as the “band” is (effectively) wider than under the gold standard. The Fed can and should ignore a single large trader, who might be engaged in market manipulation. If it sees lots of traders all going long or short, and if the Fed’s potential losses become too large, it may want to take corrective action.

Even if I were wrong about manipulation, competition among potential manipulators would keep expected NGDP growth in the 3% to 5% range (as the second manipulator could offset the first, and earn larger profits by going the opposite direction).

Here’s another metaphor. The 3% and 5% guardrails serve the same purpose as the beeping sound when trucks are backing up, and get too close to hitting something.

The basic idea here is to allow me, Scott Sumner, to get filthy rich if the Fed screws up the way they did in 2008. Since I’m a fatalist who never expects to get filthy rich, I would not expect the Fed to screw up under my proposed guardrails regime. I hope I’m wrong!!

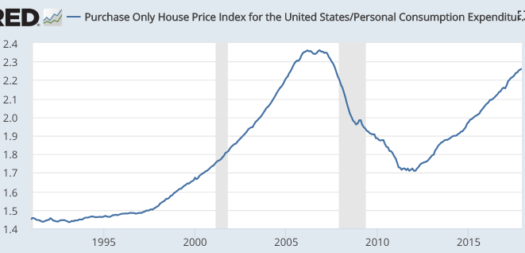

So let’s see what these pundits say today. Are they calling for investors to engage in “the big short”, as John Paulson did in 2008? Are they predicting another Great Recession? Are they predicting another crash in housing prices? Are they predicting another banking crisis? If not, why not?

So let’s see what these pundits say today. Are they calling for investors to engage in “the big short”, as John Paulson did in 2008? Are they predicting another Great Recession? Are they predicting another crash in housing prices? Are they predicting another banking crisis? If not, why not?