More articles

1. Tyler linked to an interesting article on Portugal. This caught my eye:

Then, in 2023, the Immigration Control Agency was dissolved, ostensibly in response to an extremely uncharacteristic display of violence where, in March 2020, two officers beat a Ukrainian man to death in the airport of Lisbon.

No protests followed the unjust death of this man on Portuguese soil. This makes for an illustrative contrast to when, three months later, the June 2020 Black Lives Matter protests were, just in Lisbon, attended by over 5000 people, decrying the death of an African-American man 6000 kilometers away on New World soil.

2. Is there a double standard in the US attitude toward human rights? Is the Pope Catholic?

Consider this: In 2023, suspicion swirled that the Indian government was connected to the killing of a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil and a plot to kill a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil—a remarkable set of allegations. Yet even more remarkable than the allegations were the reactions. The U.S. government opted to douse the potentially incendiary fallout, saying little, merely allowing the case to wend its way through the courts. In other words, Indian hubris was accommodated, not chastised. It was a testament to India’s newfound political standing.

What if it had been China?

3. East Asian governments have a new interest in boosting stock markets. I wonder why? Here’s the FT:

Rekindled investor interest in China’s state-owned behemoths would also reflect their continued economic prominence and an ongoing campaign by Beijing to improve financial performance. As their biggest shareholder, the central government stands to benefit from higher valuations and larger dividends.

“SOEs used to have lower revenue growth, lower returns on equity and much higher balance sheet leverage than private companies. But after 2020, we’ve seen SOEs improving,” said Winnie Wu, a strategist at BofA Securities in Hong Kong.

There are parallels with government campaigns in Japan and South Korea to improve stock market valuations, she said, noting that buying into SOEs might suit fund managers with benchmarks that require exposure to China.

4. Disney bought a huge area in central Florida out of frustration that urban development in Anaheim had hemmed in their original Disneyland. But it turns out that even in Anaheim they had much more land than they thought, and plan a 50% expansion into their vast parking lots.

The development agreement the city is agreeing to maps out where new theme park construction could occur over the next 40 years, giving Disney flexibility to determine what exactly would be built – though all still within the footprint of its current properties. The goal, Disney officials say, is to use underutilized land around the resort to build immersive experiences in Anaheim as the company has done elsewhere around the world.

Because of high land prices, suburban parking lots in Orange County have become gold mines.

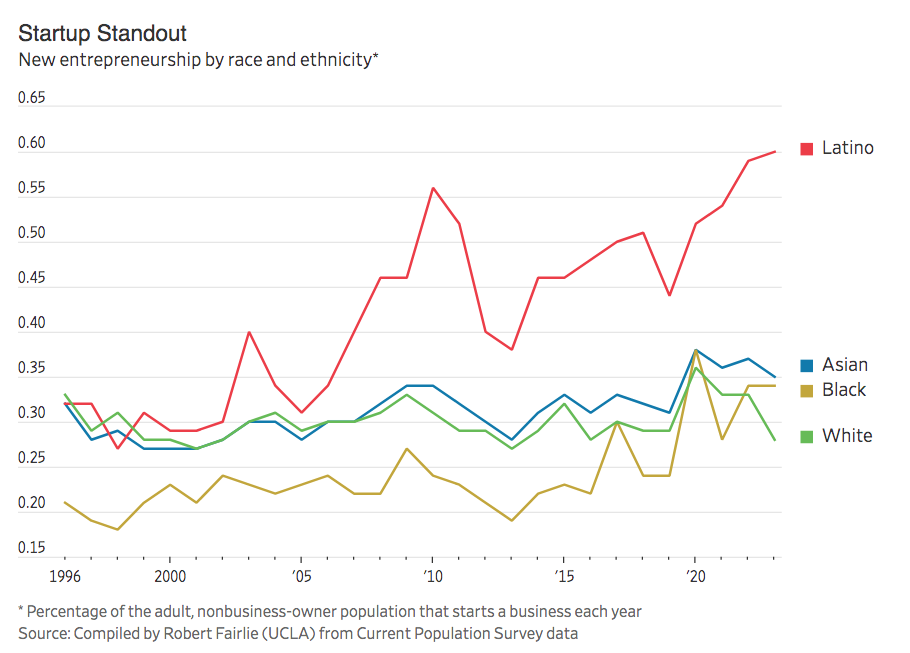

5. Perhaps our immigration policy should steer clear of whites, and focus on cultures that are more likely to be entrepreneurial, like Hispanics, Asians, and blacks. From the WSJ:

6. The new right faces a problem. If they ever succeed in taking over our institutions, they lack an elite capable of running these institutions. As a result, they might be better off moving away from their current infatuation with government power, and switch to classical liberalism. Here’s John McGinnis:

As a result of the New Right’s mismatch problem, an intensification of the classical liberal program may paradoxically be more likely to achieve indirectly the objectives of the New Right than its own misguided program for more state power. For instance, if the momentum of school choice programs continues, competition may naturally deliver a more patriotic and family-friendly education than government schools, because that is what most parents want. The policy matches sociology: school choice empowers a group more friendly to the New Right (parents) and disempowers a group (teachers—who are more hostile to it).

Similarly, a program of deregulation disempowers bureaucracy and groups within a corporation that are hostile to conservative views. The result is likely to be a less woke corporate world.

7. The WSJ headline says:

Could Fossil Fuels Re-Elect Biden?

But the story says exactly the opposite:

The U.S. economy last year expanded by 2.5%, and while the rest of the press missed it, fossil-fuel producing states led the way. These include North Dakota (5.9%), Texas (5.7%), Wyoming (5.4%), Oklahoma (5.3%), Alaska (5.3%), West Virginia (4.7%) and New Mexico (4.1%). Mining contributed about two to three percentage points to GDP growth in these states.

GDP growth in most other states was sluggish, especially those in the Northeast like New York (0.7%) and New Jersey (1.5%) and the Great Lakes region. Mr. Biden boasts about a Midwest manufacturing boom, but folks aren’t feeling it in Wisconsin (0.2%), Ohio (1.2%), Illinois (1.3%) Indiana (1.4%) and Michigan (1.5%).

Biden’s industrial policy looks like a dud, and the energy states are not the swing states that he needs to win.

8. According to a recent article in the FT, relatively affluent Hong Kong is less technologically advanced than Beijing, capital of a middle income country:

I moved to Beijing this month, one of a trickle of correspondents recently granted entry to mainland China after expulsions and the pandemic drained our numbers. On my first evening, I ordered some paracetamol on the popular delivery app Meituan. It arrived in 20 minutes, brought to my hotel room by an affable, metre-tall white robot. “Thank you, see you again soon,” it chirped before rolling away.

This was a novelty for someone who had come from the technological backwater of Hong Kong, where newspaper stands, trams, diesel engines and cash keep you firmly rooted in the last century. Suddenly, I was thrown into the dazzling array of apps and automation that eases friction in this sprawling metropolis — from services such as ride hailing, housekeeping and food delivery to a hotel elevator equipped with facial recognition technology that automatically whisks me to the correct floor.

Not sure what to make of this, but it’s interesting. (I’d still prefer to live in Hong Kong.)

9. America’s first high speed rail will go from Las Vegas to the bustling metropolis of Rancho Cucamonga. Your tax dollars at work: