What do you mean by “religion”?

Social scientists occasionally examine the impact of religion on various socioeconomic indicators. But what do we mean by religion?

Should we think of religion in theological terms—say those who follow the teachings of various religious prophets?

Or should we think of religion in terms of cultural practices that are linked with religion (such as prudishness), even if those practices have little or nothing to do with the religious documents on which the religion is supposedly based?

Or is a religious group a sort of tribe–like fans that are loyal to a particular football team? Based on what I’ve read about the Catholics and Protestants of Northern Ireland, the conflict there has little or nothing to do with religion as I think of the term.

Each of these three definitions would lead to very different implications in terms of the impact of religion on society. Here’s Norman Douglas describing the religious views of South Italians:

For the same reason the adult Jesus—the teacher, the God—is practically unknown. He is too remote from themselves and the ordinary activities of their daily lives; he is not married, like his mother; he has no trade, like his father (Mark calls him a carpenter); moreover, the maxims of the Sermon on the Mount are so repugnant to the South Italian as to be almost incomprehensible.

So “turn the other cheek” is not popular in Sicily?

Monkish ideals of chastity and poverty have never appealed to the hearts of people, priests or prelates of the south; they will endure much fondness in their religion, but not those phenomena of cruelty and pruriency which are inseparably connected with asceticism; their notions have ever been akin to those of the sage Xenocrates, who held that “happiness consists not only in the possession of human virtues, but in the accomplishment of natural acts.” Among the latter they include the acquisition of wealth and the satisfaction of carnal needs. At this time, too, the old Hellenic curiosity was not wholly dimmed; they took an intelligent interest in imported creeds like that of Luther, which, if not convincing, at least satisfied their desire for novelty. Theirs was exactly the attitude of the Athenians towards Paul’s “New God”; and Protestantism might have spread far in the south, had it not been ferociously repressed.

That final sentence (from a book written in 1915) might be viewed as a sort of prediction. So how’s Protestantism doing in Latin countries today? Here’s The Economist:

Evangelical Christianity is the fastest-growing religion in the region. Polls on religious beliefs vary widely, but around a fifth of Latin Americans identify as evangelicals, up from a tenth in 2002. In Guatemala and Honduras, they are set to overtake Roman Catholics as the dominant religion by 2030. This could happen in Brazil by the mid-2030s, too. In the past decade, a new church has opened in Brazil almost every hour, of which 80% were evangelical.

In the 1970s enterprising pastors, inspired by those in the United States, introduced a strand known as neo-Pentecostalism. This preaches the “prosperity gospel”, a radical reinterpretation of the Bible which claims that earthly wealth is a sign of divine blessings.

I suspect that Douglas was correct about southern Italy.

Researchers often discuss the impact of religion by pointing to various aspects of life in Catholic areas, or Protestant areas, or Mormon areas, or Moslem areas, of Confucian areas, or Hindu areas. I have no problem with that sort of study, but it seems to me that these studies are implicitly defining a religion as a cultural group, not a theology. They are describing the cultural practices of people that live in various regions, and attaching the term “religion” to those practices.

And that’s fine. But then don’t be surprised if the religious labels change, as we are currently seeing in Latin America. In a free market, cultures will gravitate toward the religions that provide the best fit. It would be much more interesting if the culture were to change (which also happens occasionally.)

PS. Here’s Jonathan Dean discussing Stephen Wolfe’s “The Case for Christian Nationalism.”:

Rather than appealing to the real, historical meanings of words like Christianity and nationalism, the ideology extrapolates from subjective experience. It is “Christian” to the degree that a person understands their life experience as definitively Christian; it is “nationalist” to the degree that a person understands their life experience to be representative of the character of their nation. In other words, Christian nationalism means little more than the experience of one’s life enforced on one’s neighbor by force. When terms are treated like this, communication—and, therefore, politics itself—becomes impossible. A reliable and accessible epistemic method is necessary for a community to function, and Christian nationalism, as Wolfe presents it, simply doesn’t have one. He can tell us nothing of Christianity or nationalism; all he can communicate is the Christian nationalism of himself—and himself alone.

I look forward in a few years to “The Case for Christian Fascism.”

PPS. The New Right favors a muscular government that uses its power to go after the left. Stephanie Slade of Reason pushes back against this view:

That radical, countercultural message is far too often absent on the right today. As the Catholic writer Leah Libresco Sargeant puts it, “A lot of social conservatism has defined virtue down to ‘refraining from certain modern errors’ rather than ‘living a life shocking in its generosity, courage, etc.'”

To truly care about virtue is to recognize that it matters how you win: Ends don’t justify means. If conservatives ever did have to choose which side of the barbed wire to be on—as the gulag inmate accepting persecution or the victor carrying it out—there would be only one right answer from a Christian perspective. It isn’t the New Right’s.

PPPS. After writing this post, I heard an interview of Russell Moore on NPR, a former leader of the Southern Baptist Conference Convention:

DETROW: Moore’s new book, “Losing Our Religion: An Altar Call For Evangelical America,” is an attempt at finding a path forward for the religion he loves. When we talk this week, Moore told me why he thinks Christianity is in crisis today in America.

MOORE: Well, it was the result of having multiple pastors tell me essentially the same story about quoting the Sermon on the Mount parenthetically in their preaching – turn the other cheek – to have someone come up after and to say, where did you get those liberal talking points? And what was alarming to me is that in most of these scenarios, when the pastor would say, I’m literally quoting Jesus Christ, the response would not be, I apologize. The response would be, yes, but that doesn’t work anymore. That’s weak. And when we get to the point where the teachings of Jesus himself are seen as subversive to us, then we’re in a crisis.

Maybe that’s why church attendance is down sharply. In this day and age, who wants to be told that they should love their enemies?

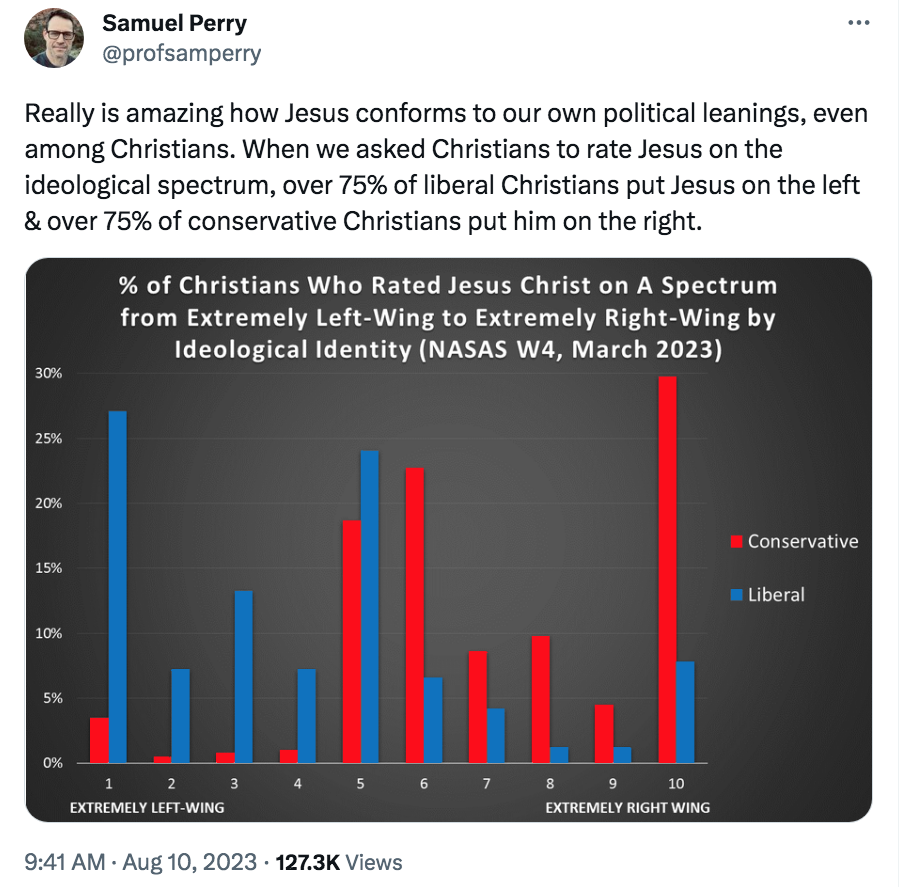

PPPPS. Matt Yglesias directed me to this tweet: