Here we go again

During the Great Recession, most people thought that bank failures were due to subprime loans. Actually, the vast majority of bank failures were caused by bad commercial loans (linked to falling NGDP.)

This time around, there will be lots of bankruptcies caused by disruptions in trade associated with the coronavirus. Then there’ll be lots more caused by tight money (i.e. low NGDP.) I predict that this financial crisis will be misdiagnosed just as was the 2008 crisis. I predict that people will assume it’s just C19, and ignore the role of falling NGDP.

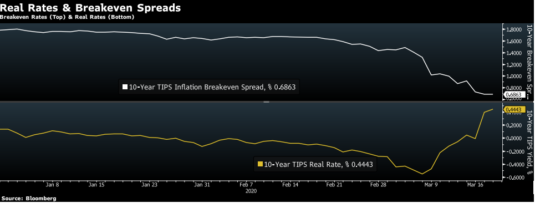

I predict that just as in 2008, people will not even understand that monetary policy is highly contractionary.

I predict that just as in 2008, the Fed will fail to adopt level targeting and a “do whatever it takes” approach to QE.

I predict that the economy will fall below the Fed’s 2% inflation target, even though inflation should rise during an adverse supply shock.

I predict a fiscal stimulus package that will be just as ineffectual as the 2008 and 2009 packages.

I predict bailouts of politically influential failed companies (as during the Great Recession), rather than monetary stimulus that aids all companies.

And everything will be worse in Europe, just as during the Great Recession.

To be fair, the real shock this time is far, far bigger, more than 10 times bigger. Monetary policy can avoid making it worse, but (unlike in 2008-09) cannot prevent a severe recession. The sad thing is that we aren’t even doing the minimum, we are not going to avoid making it much worse. Right now, it looks like a highly contractionary monetary policy is causing 2021 NGDP expectations to plunge, and making the debt crisis far worse than it needs to be. Let’s hope for a medical miracle.

And hope that all of my predictions turn out to be false.

PS. Here’s another prediction. In a few weeks, people are going to start touting the Chinese model. Don’t believe the hype. Look to the democratic countries of East Asia—those are better models for how to handle an epidemic.

China is a polarizing country. People regard it either a some sort of economic miracle or a house of cards that’s about to collapse. It’s neither. It’s just another country.

PPS. A comment on this tweet:

Actually, China did not manage to contain the virus in one province. With the except of Tibet and a few other places, it spread all over the country. Many provinces had roughly 1000 reported cases. (And undoubtedly additional unreported cases.) This is good news; it suggests that even nationwide epidemics can be controlled.