Is Trump winning? (yes and no)

Here’s Tyler Cowen in Bloomberg:

What about trade and immigration, two issues dear to the heart of President Donald Trump? In those areas I expect to see surprisingly few changes. Fears about China are bipartisan, and with his quest for a market-boosting trade agreement with China, Trump is turning out to be a trade dove, relatively speaking. Meanwhile, on NAFTA, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives is holding up the renegotiated agreement.

Most important, I don’t see the major Democratic presidential candidates making a big public push for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the World Trade Organization or any other trade agreements. The era of greater skepticism about trade and globalization is probably here to stay, and it counts as one of Trump’s ideological triumphs.

And immigration? Well, I don’t expect our next president to separate arriving children from their parents. But neither do I expect a big breakthrough on immigration policy. Are any of the leading Democratic candidates putting forward a grand immigration plan for public debate? No, even though in other areas they are quite willing to think big. They realize that in terms of intensity, America is moving to the right on immigration — as it did a century ago, leading up to the 1920s restrictions. Count that as at least a half-triumph for Trump.

I don’t think this is right; I don’t believe Trump’s had any ideological triumph’s—just losses. Although I don’t intend to contest the view that Trump personally has been successful with these topics as issues. He won in 2016 and might win in 2020. But in two other areas, one obvious and one less obvious, I think he’s failed. Start with the obvious; this is from today’s news:

“But illegal immigration is simply spiraling out of control and threatening public safety and national security.”

Someone suffering TDS? No, the official in charge of Trump’s immigration enforcement program. Trump’s more than half way through his term, and he’s completely failed to do anything about the single most important issue in his campaign.

I also disagree with Tyler’s comparison of the mood in America today with the 1920s, where there was fairly broad support for restricting immigration. I get that Tyler notes the “intensity” of the anti-immigration crowd. Indeed he has to, as the polls clearly show increasing support for immigration. (I doubt that was the case in the 1920s.) But I think it’s more complicated than that, with three groups involved, not just two.

You have 3% to 5% of the US population directly impacted by immigration crackdowns, and they intensely oppose Trump. Another 30% are fairly strongly opposed to immigration, for nationalistic or economic reasons. And then there are about 65% of people who don’t pay a lot of attention to the issue, but are becoming increasingly sympathetic to immigrants. Importantly for the future, the young are especially strongly moving in favor of immigration.

Does this sound familiar? How about 3% to 5% of Americans are gays who intensely support gay marriage, 30% strongly oppose it for religious/cultural reasons, and 65% who don’t give it much thought, but are increasingly in favor? How’d that issue play out over time? Gays benefited from a media that increasingly portrayed them sympathetically as real people, not caricatures. Isn’t the same beginning to occur with illegal immigrants?

Where Trump may win is the politics of immigration, even while losing on policy. While he ran in 2016 as a dealmaker who could get things done, a man who would force Congress to do his bidding, we’ve discovered he’s actually an appallingly incompetent dealmaker. Now he portrays himself as a victim of faceless “elites”. His supporters lap this up, so it may not matter if Trump fails to enact Trumpism; he’s not really the President, just the “Troll in Chief”. He might be re-elected on that basis, with the help of the hapless Dems. (I think it’s a toss-up.)

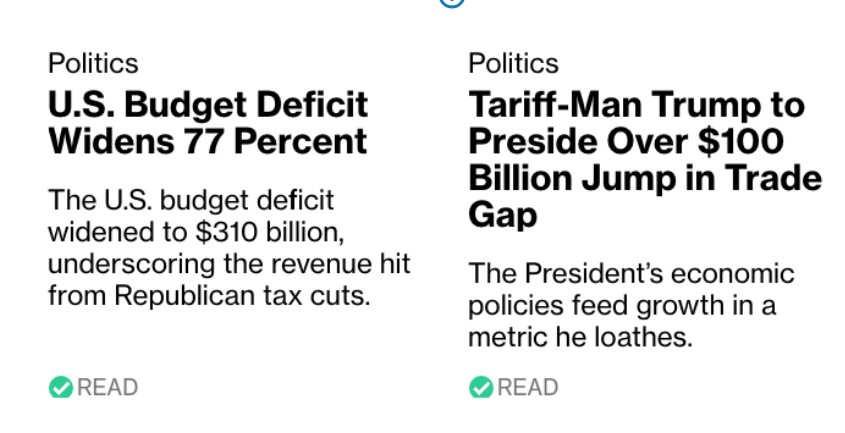

Trump is also losing badly on the single most important trade issue in his campaign–the deficit. Here’s a set of Bloomberg stories that appeared side by side, and caught my eye:

Hmmm, I wonder if there is any relationship? The trade deficit article had this observation:

The strong dollar matters because it has led to near-record deficits in manufactured goods and non-oil goods that are being masked by increases in exports of oil and services, [Robert] Scott said. To his mind that means the U.S.’s trade balance is worse than even the official data reflects. “There’s a lot going on below the surface here,’’ he said.

It is rather striking that the trade deficit is getting larger just as the fracking boom is dramatically improving our net export position in oil.

Tyler argues that the establishment has adopted Trump’s trade skepticism, while simultaneously arguing that Trump is actually somewhat of a trade dove. I suspect this is an example of Tyler using a bit of hyperbole to be provocative and contrarian. OK, I’ll take the bait.

The establishment has always held a “pragmatic” view of trade, where free trade was good as long as other countries played fair. (In contrast, economists believe free trade is the best policy even when other countries don’t play fair.) So I don’t think the establishment has moved in Trump’s direction, it’s always been right where it is now. It’s been hard to sell the Dems on free trade ever since the 1960s.

On the other hand, Democratic voters are moving very strongly in the free trade direction. You might argue that a steelworker in Ohio who votes for Sherrod Brown has more “intense” views on trade than a barista in San Francisco who likes imported coffee. But there’s one big problem with that. Steelworkers in Ohio are no longer Democrats, and the future of the Democratic Party is obviously not people like Sherrod Brown. Heck, I remember lots of Dems like him when I was a teenager. He’s a dinosaur. The barista in San Francisco is the future of the Democrats, which will eventually become the pro-immigration, pro-trade party.

[In the UK, the older Labour leaders (Corbyn) are skeptical of free trade, but the younger voters are super supportive of the EU. BTW, watch the Brexit end-game closely; just as Thatcher predicted Reagan, Brexit predicted Trump.]

I’m not at all optimistic about the politics of America. The 2020 election is likely to feature an awful Democrat and an even worse Republican. The budget situation is bad and will get worse. But I am pretty optimistic about trade and immigration, as I think Trump’s clearly lost on both issues and things will soon swing our way. I expect the Trump people to eventually admit that the trade deficit doesn’t matter, and indeed is often a sign of a prosperous economy. Trump cares about “winning ” more than he cares about ideology. That’s why he’s tough on Iran and soft on N. Korea; he wants to undo whatever Obama did. If Obama had done the deal with Korea, not Iran, Trump’s positions would be reversed.

I recently happened to overhear some of the most moronic talk radio I’ve ever encountered. I used to occasionally listen to Rush in the early 1990s, and he often sounded fairly intelligent, at least compared to the current right wing nuts on the radio. One tirade that caught my attention was a guy saying something like “how dare they impeach Trump, he’s been so successful”, and then cited his trade deals. No, I’m not making that up—his trade deals were cited as a policy success. (It may have been Sean Hannity, I’m not sure.) So while in substantive terms Trump has failed on trade, his supporters seem happy to accept hollow trade deals that entrench the neoliberal leviathan ever more deeply into the global economy.

And that’s really good news. Imagine if his supporters actually cared about seeing the alt-right agenda put into place. Steve Bannon must be feeling pretty lonely right now.