David Beckworth recently interviewed Adam Ozimek for his podcast series, and the discussion focused on monetary policy. Ozimek pointed out that not enough attention was being paid to the lessons to be learned from the past three years of Fed policy. The Fed began raising rates in December 2015, and even Fed officials now admit that this was too soon. Or do they? That’s one of the issues they discussed.

Ozimek points to interviews with some top Fed policymakers who seem to agree that the natural rate of unemployment is considerably lower than what the Fed estimated back in 2015, and also that the stance of monetary policy back then was less accommodative than the Fed had assumed. Ozimek wants them to draw the obvious implication from that fact—that policy was too contractionary in late 2015. There’s really no other plausible interpretation of the statements he cites, but Fed officials don’t quite seem to come out and explicitly make that admission. This relates to my recent Mercatus policy brief, where I call on Congress to insist that the Fed periodically evaluate previous policy decisions, based on incoming data.

I also tended to view Fed policy as being slightly too expansionary contractionary during 2015-16, although mostly based on their undershooting of the 2% inflation target. Like the Fed, I underestimated the extent of the decline in the natural rate of unemployment (Ozimek and Beckworth were ahead of me on that point.) So what implications can we draw from this episode?

1. I believe it’s important to put this policy error in perspective. It was a consequential error, perhaps costing hundreds of thousands of jobs for a couple of years. That’s hardly trivial. At the same time, the error was an order of magnitude less damaging and an order of magnitude less inexcusable that the policy errors of 2008-15. When figuring out what went wrong with monetary policy, we need to focus almost all our attention on the mistakes of 2008-15. That’s the elephant in the room.

2. This episode illustrates the danger of basing Fed policy on estimates of the natural rate of unemployment (Un). The Fed cannot accurately estimate the natural rate in real time, and hence it’s an exceedingly poor guide to policymakers. The lesson is not “next time do a better job estimating Un”, it’s “stop trying to estimate Un, and start focusing on variables than you can measure, like NGDP.” Under NGDP level targeting, there is no need to even measure the unemployment rate—it plays no role in monetary policymaking.

Unfortunately, the Fed is forced to rely on natural rate estimates as long as it targets inflation under a dual mandate approach, as the unemployment rate helps it to determine how much “catch-up” they need to do after a policy miss. One of the advantages of NGDPLT is that the Fed is no longer forced to try to do the impossible—estimate Un.

They also discussed some research Ozimek did on the relationship between population growth and inflation. I have not read the research, but if I’m not mistaken the study found a positive correlation between growth in working age population and inflation, both cross sectionally and over time. Ozimek hypothesizes that this may relate to the impact of population growth on real estate prices.

The cross sectional correlation makes sense to me. Cities that are growing fast tend to have higher real estate prices than cities shrinking in population, such as Detroit. The time series correlation is less intuitive. Inflation is determined by monetary policy. It seems unlikely that the optimal monetary policy calls for higher inflation when population growth is more rapid. So what’s going on? My best guess is that the correlation somehow relates to the link between population growth and interest rates, or perhaps population growth and the natural rate of unemployment:

1. Under the gold standard, price levels were positively correlated with nominal interest rates. That’s because higher nominal interest rates boosted the opportunity cost of holding gold, which led to less demand for gold, which is inflationary under a gold standard. Because the expected rate of inflation is roughly zero under a gold standard, anything that boosted the real interest rate, such as faster population growth, also boosted the nominal interest rate, and hence inflation.

2. In Japan, shocks that reduce the real interest rate seem to be deflationary, as they reduce the opportunity cost of holding yen, thus boosting the demand for yen and the value of yen. Lower population growth might reduce the real interest rate in Japan. Of course the BOJ should offset this, but they often do not do so. Interestingly, they seem to have done better since 2013, enough so that the inflation rate in Japan has risen slightly, even as growth in the working age population has fallen sharply. Over longer periods of time, however, the inflation/population growth correlation in Japan supports Ozimek’s claim.

3. Baby boomers started entering the labor force in the late 1960s. By itself, that’s not inflationary at all, even if it boosted real estate prices. Recall that real estate prices are a relative price, and relative price increases are not inflationary unless they reduce aggregate supply. But faster population growth does not reduce AS. So what explains the Great Inflation? One factor may have been a misinterpretation of the Phillips Curve relationship. The faster growth in the labor force (especially among the young and women), led to a rise in the natural rate of unemployment during the 1970s. At the time, the Fed made exactly the opposite mistake as in 2015—they underestimated Un. This caused monetary policy to be too expansionary, in a futile attempt at holding down the unemployment rate. Just one more reason not to use monetary policy to target unemployment.

4. Reverse causation. If monetary policy is procyclical then inflation will also be procyclical. In that case, rising inflation will be associated with growing RGDP. It will also be associated with a rising population, as the boom draws in immigrants from places like Mexico.

Note that all four of these explanations are entirely ad hoc, so I wouldn’t necessarily expect the correlation between population growth and inflation to hold in the future, at least at the national level. Basically any correlation one finds is evidence of sub-optimal monetary policy, just as the Phillips Curve relationship is evidence of suboptimal monetary policy.

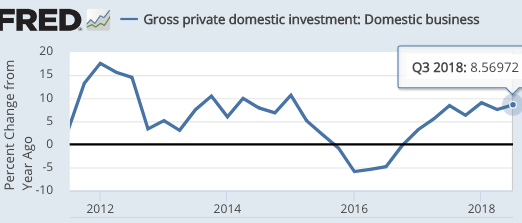

PS. Why is Trump trying to drive down oil prices? In the second half of this post, I showed that high oil prices now tend to boost industrial production—mostly due to fracking. Doesn’t Trump want more industrial production? Look at investment growth in late 2015 and 2016, when oil prices were low.

PS. Why is Trump trying to drive down oil prices? In the second half of this post, I showed that high oil prices now tend to boost industrial production—mostly due to fracking. Doesn’t Trump want more industrial production? Look at investment growth in late 2015 and 2016, when oil prices were low.