Suppose the Fed always aims for 2% inflation

Tim Duy has a good post explaining why the Fed is unlikely to opt for “overshooting.”

I was re-reading some of the recent overshooting debate and it occurred to me that it is comical that we are even having this discussion. The Fed is not going to deliberately overshoot inflation, period. That train left the station long ago. So long ago that you can’t even here the rumble on the tracks.

The train left the station on January 25, 2012, with this statement by the Federal Reserve:

The Committee judges that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.

On that day, the Federal Reserve locked in the definition of price stability. They locked it in specifically to prevent even the appearance they might deliberately overshoot as a result of extraordinary monetary policy. They locked it in as a commitment device to tie the hands of future policymakers as they would need to justify changing the definition of price stability, presumably a very high bar for any central banker to cross.

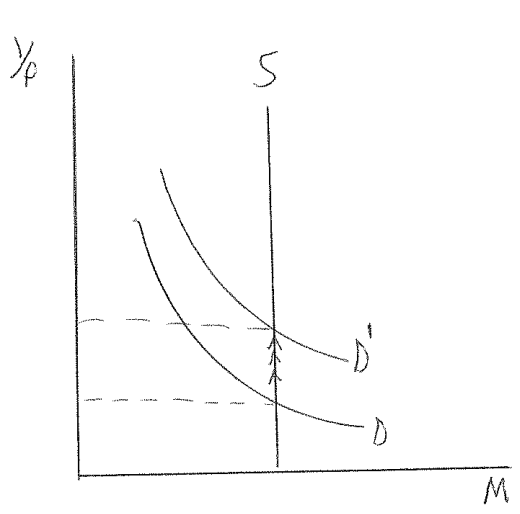

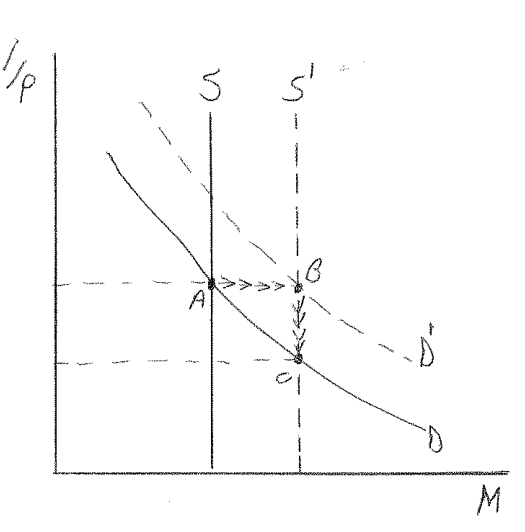

That’s probably correct. But it does point to some confusion at the Fed. The Fed seems pretty committed to their dual mandate, but doesn’t seem to understand what it implies. Let’s start with a simple policy rule. Suppose the Fed never aimed for above target inflation. Also suppose they aim for 2% inflation, on average. In that case it would be a logical necessity for the Fed to never aim for below 2% inflation. Which means that they would always have to aim for exactly 2% inflation going forward.

Now that is a defensible policy (although I would oppose it.) But it certainly is not a policy consistent with a dual mandate. It would be a single mandate inflation target (IT), pure and simple. Fed officials often seem confused on that point. They talk about the need to aim for 2% inflation, even when unemployment is high. But that means they are behaving exactly as they would behave if Congress had given them an IT single mandate. In other words, they are behaving exactly as they would if their mandate was set by the right wing of the Republican Party. Even now, under Janet Yellen, the tapering and prospective interest rate hikes are aimed at boosting inflation back up to 2%. The policy is exactly the same as it would be if the Fed did not care about unemployment at all.

I suppose 99% of people would look at this picture and see all sorts of grand conspiracies. The Fed is in the back pocket of the bankers, the bondholders, the creditors, the coupon clippers. But I’m different, I’m a hopelessly naive fool who actually thinks the Fed is trying to do a good job, but just lost its way. And why do I believe the Fed is actually not corrupt, despite all the evidence pointing to their violation of the dual mandate over the past 5 years? Two reasons:

1. The top Fed officials tend to be economists. Both actual voters like Bernanke and Yellen, and also the all important staff people who set the agenda.

2. As far as I can tell the vast majority (not all) of economists who are not at the Fed, who have no financial interest at all in helping bankers, even economists who favor increased welfare spending, a higher minimum wage, help for the unemployed, and all sorts of other left wing causes, seem equally confused about monetary policy as the economists who are at the Fed.

So one possibility is that clueless economists join the Fed, and instantly become both highly intelligent and corrupt at the same moment. That’s what the critics who call me naive seem to think. However I think it much more likely that when they join the Fed their competence and honesty don’t change very much. They are trying their best, and making the same mistakes as their private sector counterparts make when asked about monetary policy. They think it’s “natural” that we have deflation in a deep slump like 2009, whereas their mandate actually implies that inflation should be countercyclical; above target when unemployment is high, and vice versa.

If this interpretation seems naive, then I plead guilty.

PS. Tim Duy has another good post on this subject:

If the most dovish member of the FOMC can tolerate no more than a 25bp upside miss on inflation, what does it say about the other FOMC members? Regardless of whether this is Kocherlakota’s max or the best he thinks he can get, it tells you that 2% is really a ceiling, not a target. Now, generously, it maybe that the FOMC believes that they cannot exceed 2% politically given the amount of extraordinary stimulus already in place. But that still leaves 2% as a ceiling.

PPS. I do realize there are lots of other interpretations (none good.) For instance, the bubbleheads may have gained influence, and the worry about bubbles may be roughly offsetting worry about unemployment, leaving us with a 2% inflation target (which we will likely fall short of.)

HT: Travis V