If it’s an identity does that mean I’m right?

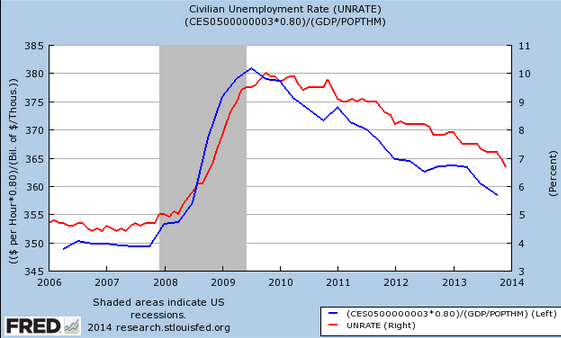

My musical chairs model of the economy assumes nominal hourly wages are sticky. In that case fluctuations in NGDP may be highly correlated with changes in the unemployment rate. Arnold Kling doesn’t like the empirical evidence I found in support of the model:

Scott is fond of saying, “Never reason from a price change.” I say, “Never draw a behavioral inference from an identity.”

I think Arnold knows it’s not an identity. If you graphed MV and PY, you’d observe only one line, as the two lines would perfectly overlap. In the graph I presented the two lines were correlated but far from perfectly correlated. So it’s no identity. I’d guess the gaps would be far larger in many other countries, such as Zimbabwe.

A better argument would be that the correlation doesn’t prove that causation goes from NGDP to unemployment. After all, changes in NGDP could cause changes in hourly nominal wage rates, leaving unemployment roughly unchanged. In that case the correlation I found would be spurious. If I left the impression that the correlation proved nominal wages were sticky that would have been a “behavioral inference,” and hence a mistake. What I tried to do was assume nominal wages are sticky (as they obviously are), and then show the effect of NGDP shocks in a world where nominal wages are sticky.

My musical chair model doesn’t have the “microfoundations” that have been fashionable since the 1980s. But which model with microfoundations can outperform the musical chairs model? Indeed let’s make the claim more policy-oriented. I claim that fluctuations in predicted future NGDP relative to the trend line strongly correlate with changes in future unemployment. And of course NGDP futures prices are 100% controllable by the monetary authority.

There is no NGDP futures market? You can’t use that against my claim as I’ve been advocating such a market since 1986. It’s an embarrassment to the economics profession that this market doesn’t exist (yet.)

So yes, it sort of seems like a tautology, but perhaps that’s because I’m right.

PS. Imagine one of the great controversies in physics (say string theory) could be settled with a particle accelerator that cost $500,000 to build. But the physics profession was too lazy to ask the NSF for the money. Replace string theory with the debate over demand-side vs. RBC models and you have described economics circa 2014.