Mark Sadowski has some nice comments that provide data backing up a comment in my previous post. When I was young the Fed liked to blame inflation on the fiscal authorities. Suppose you asked the Fed the following question in early 1968:

LBJ plans to raise income taxes to slow inflation. If he does this will you offset the effect with easier money, thus preventing a fall in inflation?

I guarantee the answer would have been no. But they did! Inflation rose from a little over 4% in 1968, to around 5% to 6% in 1969 and 1970. It did fall modestly in 1971 and 1972, due partly to price controls. However NGDP growth continued at a very rapid rate throughout the 1970s. And note that this policy failure occurred well before the first oil shock of late 1973. Here’s Mark:

The delusion that fiscal deficits were one of the primary causes of the Great Inflation is still very widespread. This delusion can often be cured with the simple facts.

True, fiscal policy was expansionary in fiscal years 1964 through 1968. The cyclically adjusted Federal budget balance was reduced from (-0.5%) of potential GDP in fiscal year 1963 to (-4.4%) in fiscal year 1968, and the deficit was increased annually during that time:

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43977_AutomaticStablilizers3-2013.pdf

But a 10% income surtax was enacted in 1968 and remained effective through 1970. The cyclically adjusted budget balance rose to (-1.1%) by fiscal year 1970 and remained in the relatively narrow range of (-2.7%) to (-1.3%) from fiscal year 1971 through 1982. In fact despite the image of a deficit prone decade the 1970s were one of the most fiscally responsible decades on record with gross Federal debt setting a post WW II record low of 32.5% of GDP in fiscal year 1981 (President Carter’s last budget).

True between 1963 and 1968 NGDP growth averaged 8.1% and core inflation (to strip out the effects of energy prices) accelerated from 1.3% in 1963 to 4.4% in 1968:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=155542&category_id=0

But NGDP growth was double digit every year from 1976 through 1979, peaking at 13.0% in 1978, and core inflation accelerated to 9.2% by 1980.

Then, under Reagan, cyclically adjusted Federal budget balance was reduced from (-1.5%) in fiscal year 1981 to (-4.6%) in fiscal year 1986 (the largest cyclically adjusted budget deficit since 1960 prior to the Great Recession). And yet from 1981 to 1986 NGDP growth averaged 7.4% and core PCEPI fell to 3.4% by 1986.

The Great Inflation and the Great Disinflation are perhaps the greatest examples of monetary offset of fiscal policy away from the zero lower bound in US history, because fiscal policy was relatively tight during the height of the Great Inflation, and became exceptionally loose during the Great Disinflation, exactly the opposite of what fiscalists predict.

Yes, the US was not at the zero bound, but this directly addresses Matt Yglesias’s point about central banks denying that they engage in monetary offset. We know for a fact that in the past they have denied doing so even as they did engage in offset. Mark has more great evidence from Japan, and some of this does occur at the zero bound:

The following is from my guest post at Historinhas “Richard Koo also misinterprets Japan´s lost decades (Part II)” on June 11, 2013:

“…In my opinion the most objective way of judging fiscal policy stance is the change in the general government structural balance. The structural balance is adjusted for the business cycle and thus any changes should represent policy rather than the state of the economy. The IMF provides estimates of Japan’s general government structural balance from 1994 on so we can compute the changes from 1995 on:

http://thefaintofheart.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/sadowski2b_4.png

With the exception of calendar years 1997 and 2001 fiscal policy was expansionary during 1995-2003. Do we know anything about the fiscal policy stance prior to 1995? An excellent summary of the Japanese discretionary fiscal stimuli programs is Anita Tuladhar and Marcus Bruckner’s “Public Investment as a Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Japan’s Regional Spending during the 1990s” (IMF Working Paper No. 10/110, April 2010). Appendix Table 8 lists two fiscal stimuli for 1993 and one each for 1992 and 1994, so fiscal policy was obviously expansionary for the entire 1992-96 period. It also lists nine fiscal stimuli and three tax cuts during 1995-2002, but none during 2003-07. The fiscal tightening in 1997 is explained by the fact that Japan raised its consumption tax from 3% to 5% on April 1, 1997. The fiscal tightening in 2001 seems to have been passive. The expansionary fiscal policy of 2003 represents a carryover of the effects of the 2002 fiscal year, which ended on March 31, 2003.

Considering that the BOJ’s call rate wasn’t lowered below 1% until July 1995 and didn’t get below 0.25% until November 1998, Japan’s fiscal policy seems a bit backwards. Away from the zero lower bound there’s absolutely no rationale for doing fiscal stimulus unless one wants to see the spectacle of competing policy levers cancel each other out, and yet Japan did eight fiscal stimuli and three tax cuts during 1992-98. On the other hand, if one truly believes in the Keynesian concept of the liquidity trap, then one would want to do fiscal stimuli when the policy rate is pinned to the zero lower bound, and yet Japan practiced five consecutive years of consolidation during fiscal years 2003-07, a time when the policy rate was never as high as 0.5%.

So with that background out of the way, and recalling that Japan’s QE was announced in March 2001 and didn’t really kick into gear until December 2001, how did the Japanese economy do? Here’s a graph of Japans’ annual CPI inflation and harmonized unemployment rate:

http://thefaintofheart.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/sadowski2b_5.png

Note that aside from the consumption tax induced increase in 1997 Japan’s inflation rate dropped nearly every year from 1991 through 2002 and then edged upward until there was consecutive years of consumer price inflation in 2006-07 for the first time in nearly a decade. Unemployment increased nearly every year through 2002 and then dropped in 2003 for the first time since 1990, and then continued to drop every year through 2007. And it’s worth noting that even the Nikkei 225 gave its thumbs up during 2003-07, with the index rising from less than 7900 in April 2003 to over 18,000 in June 2007, which is still by far the greatest stock market rally in Japan since the beginning of the Lost Decade(s)…”

So once again, the Japanese disinflation proceeded unimpeded during the time fiscal policy was exceptionally expansionary, and came to an end when fiscal policy became contractionary. This is another excellent example of monetary offset of fiscal policy, however in this case, the latter half took place at the zero lower bound, precisely when Keynesians predict monetary policy is impotent.

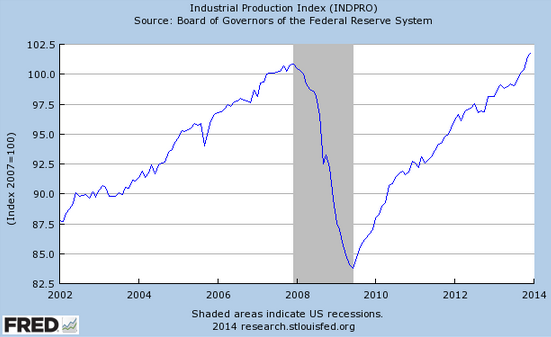

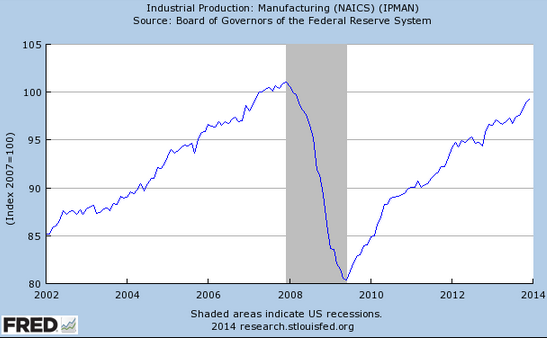

The second graph is a real eye-opener.

PS. The failed austerity of 1968-70 is one of the factors that boosted Milton Friedman’s reputation, and led to the rise of monetarism in the 1970s.