Apocalypse delayed, once again.

Time for my annual post pointing out that the China bears were wrong once again. Chinese growth is picking up again, headed for about 8% to 8.5% this year.

The Chinese people tend to make relatively large down-payments on new houses. As with all markets, mistakes will be made. But there’s no reason to believe, ex ante, that people sitting in an armchair over in America are better judges of the value of Guangzhou or Wuhan real estate that the Chinese investors themselves. And that will remain true regardless of whether Chinese property prices rise or fall over the next 12 months.

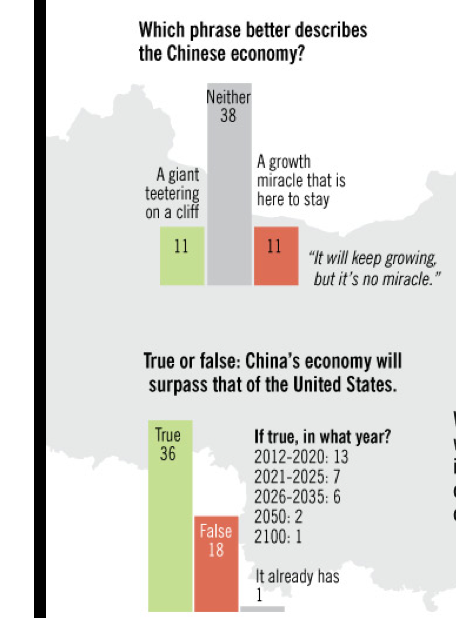

Foreign Policy did a recent survey of opinion of the prospects for China’s growth:

I answered “neither” and “It already has.” The first answer was the consensus, and the second put me in a distinct minority. A minority of one to be precise.

What makes me such a China bull? Why am I such a supporter of their government’s policies? I’m not bullish, I think China is a pathetically poor country, poorer than Mexico. I think the government is repressive and inefficient; I don’t support their policies.

Many people have trouble understanding the distinction between levels and rates of change. China used to be far more repressive and far more inefficient. During its transition to the current policy regime, it grew extremely fast, yet remains poor. That’s what you’d expect.

It is very difficult to make PPP comparisons, which are highly subjective. When I travel around China it seems to me that their cost of living is roughly half of US levels. More than half in the cities and less than half in the countryside. The Economist magazine recently did PPP comparisons for most major countries, and estimated wealthy Taiwan’s cost of living to be less than one half US levels, but China’s to be much higher than 1/2 US levels. I find that extremely implausible. But of course the bundle of goods consumed in each place is so vastly different that any comparison will be based on a set of arbitrary assumptions. If you applied the Taiwan/US price ratio to China, its GDP for 2013 (including Hong Kong) would be nearly $20 trillion, far higher than the $16.3 trillion for the US. So it’s anyone’s call. But I believe China has the world’s biggest economy right now. It leads the US in food consumption, energy consumption, exports, construction, manufacturing, and a lot of other categories.

Some day China will have a recession. And when it does the China bears will insist they were right all along. And the press will believe them. But of course they will have been wrong all along. A prediction of something that is inevitable (eventually), without a date attached, is completely and utterly meaningless. The China bears will be right if China gets stuck in the “middle-income trap”—which I think is very unlikely. How many countries with the following characteristics have gotten stuck in the middle income trap?

1. A relatively homogeneous population, with parts of the country already closing in on high income levels.

2. Booming exports of IT goods.

3. A manned space program.

4. A history of being the most advanced country in many technologies during the Dark Ages.

5. A relatively high average IQ, FWIW.

6. A culture that has a reputation for being entrepreneurial and very hard-working, as far back as David Hume.

7. Surrounded by culturally similar countries that did NOT get stuck in the middle income trap (although N. Korea has yet to leave the low income trap.)

8. A government that has been driven by pragmatic reformist ideology for nearly 30 years.

9. A culture with an intense desire to overcome earlier humiliations and become a world leader.

10. A very high saving culture, even discounting the saving forced by government.

Yes, it MIGHT get stuck, but is that really the most likely long-run equilibrium?

PS. Some China bears question the GDP data. Obviously that sort of data will be flawed in all sorts of ways. But consider data on trade, which rose from roughly $500 billion trillion in 2001 to $3.87 trillion in 2012. Does that seem consistent with a country averaging 10% RGDP growth? It does to me. I travel to China fairly often, and it sure looks like a fast growing East Asian economy, even in the interior of the country. If not, it’s a helluva massive Potemkin village.

PPS. I’m not saying that I endorse all the arguments on my list of ten Chinese characteristics. I put them there to cover a wide variety of factors that I’ve seen others discuss. I happen to think a country can reach developed country levels without a high IQ, for instance.

PPPS. The answer to my “how many countries” question is none—with Russia coming closest.