Reason magazine on NGDPLT

I love Reason magazine, but macroeconomics is not their strong suit. They recently published a critique of NGDPLT by Tom Clougherty:

Moreover, even if one accepts that a central bank is capable of hitting its growth target, that leaves open the question as to what target it should aim for. And it is not possible to know in advance what the “correct” rate of NGDP growth should be. The central bank can base its target on past growth, but even educated guesses can’t ultimately overcome this “knowledge problem.”

As London-based economist Anthony J. Evans has pointed out, if you consider 1997, the year that Bank of England began targeting inflation as your base year, and assume a 5 percent annual NGDP growth target, then you would believe that British monetary policy in the run up to the crash was more-or-less fine: NGDP growth stayed close to 5 percent throughout the “great moderation.” You would also believe that we are now significantly below the “correct” level of NGDP, and should fire up the printing presses to bring things up to scratch. If, on the other hand, you assume a 4.5 percent target since 1997, you would think that monetary policy was too expansionary in the run up to the crash, and that NGDP growth has already returned to trend””hence, time for monetary policy to “normalize”. The point here is not that 5 percent is the wrong target, or that 4.5 percent is the right one. The point is that even a small targeting error can have massive policy implications.

This criticism sounds plausible, but on closer inspection it doesn’t make any sense. In fact, either 5% or 4.5% NGDP targeting since 1997 would have been fine. What the author misses is that under either target path the volatility of NGDP would have been much lower, especially after 2007. Consider the 4.5% path. It’s true that this path would imply that monetary policy is currently right on target. What Clougherty misses is that a 4.5% NGDP path after 1997 would have resulted in far smaller gains in NGDP in the lead up to the Great Recession. About 5% less, to be specific. And this means that nominal hourly wages in Britain would also have been about 5% lower then they actually were. And since nominal wages are sticky, wage levels today would also be far lower. So the same nominal income that produces 7.8% unemployment in Britain today, might lead to only 5% or 6% unemployment if nominal hourly wages were much lower.

The easiest way to think about business cycles is to look at the interaction between changes in NGDP and changes in nominal hourly wages. When NGDP falls and wages are sticky then there will be less hours worked. You won’t see that in DSGE models, but that’s what’s actually going on. Reducing NGDP is like taking a couple chairs away in a game of musical chairs. Several participants will end up sitting on the floor. If you want to solve that problem you add chairs to the game. And if people are unemployed because of the downward stickiness of nominal wages, then you add NGDP to restore full employment.

If people are unemployed because of structural rigidities, then more NGDP probably won’t help (unless that made it more politically feasible to remove structural rigidities like extended UI benefits.)

Evan Soltas allowed me to quote from a recent email he sent out:

I am glad to see NGDPLT getting some play in the libertarian discussion, but there’s quite a bit to criticize about this piece.

(1) I do not understand the argument that macroeconomic stability would prevent sectoral rebalancing. It is a common argument, but I don’t think it withstands serious scrutiny. Macroeconomic instability ought to make sectoral rebalancing more costly.

(2) The author is wrong to suggest that an NGDP target will mean easier credit. Again, a disturbingly common argument.

(3) A “de-facto” NGDP target fails to capture one of the most important benefits — having a clear path for expectations. Many of us have written, more or less angrily, about the Bank of England because of its failure in this respect.

(4) There’s no such thing as the “correct” NGDP target. There might be a welfare maximizing trend rate of NGDP, but within a range of 3 to 6 percent, the welfare costs from missing the optimum will not be significant. I fail to see a knowledge problem. I think the author is butchering Hayek here.

(5) The paragraph recounting Anthony Evans’ argument makes no sense. So what if the extrapolated 10-year trend between 5 and 4.5 percent would capture NGDP? Deciding after the fact that you’re going to drop down onto the previous trend is the source of the problem, not anything about a small targeting error.

Tyler Cowen recently noted that Greece has had surprisingly high inflation for a country mired in a deep depression. I agree that this is a deep embarrassment for New Keynesian models. On the other hand NGDP in Greece has fallen sharply, so we market monetarists are not at all surprised by their high unemployment rate.

PS. Tyler asked the following:

Scott Sumner has a view which I do not understand, and thus do not wish to try to state, but it has something to do with not really believing in the concept of price inflation.

A few remarks:

1. Economists often discuss whether the CPI measures inflation accurately. But how can that discussion mean anything when economists have never even explained what the term ‘inflation’ means in an economy where product quality changes rapidly, and where new products are constantly introduced. Is it the amount of extra income one needs to maintain constant utility? If so, then we need to define utility. And suppose happiness surveys show no increase in happiness over 50 years. Would that mean RGDP did not rise?

2. There are many types of price indices—it’s not at all clear which one is the “right one.” I used to do lots of posts talking about how the government claimed housing prices rose 8% after 2006 and Case-Shiller said they fell 35%. Can they both be right? Sure, because inflation is a vague and poorly undefined concept, so any measure is fair game.

3. If you have what looks like a demand-side recession (a deep fall in NGDP) and are puzzled that inflation has not fallen as much as you think it should have, then you should first examine the stickiness of hourly nominal wages. If they didn’t fall, then sticky wages is your explanation. If they did fall sharply, then some other factor explains the stickiness of inflation. This might be higher VAT taxes, higher import prices, or some other sort of adverse “supply shock.”

4. If you have an adverse supply shock, then inflation should rise. If inflation falls despite an adverse supply shock, then you have both an adverse supply shock and an adverse demand shock. Both would be contributing to higher unemployment.

5. When I was researching neoliberalism back in 2007 I found that Greece had the least market-oriented economy in the entire data set (of 32 countries.) If the government is running much of the economy, various government policies may introduce a degree of price stickiness. Tim Duy has a post that discusses one example. And Tyler responds. I think Tyler’s right about the unreliability of Phillips Curve models, but I’d make the following observation, FWIW:

Tim’s graph shows inflation falling from about 3% to 4% before the recession to about minus 1% today. In the Great Depression in America inflation fell slightly more than twice as much, from zero to minus 10%. Does that difference surprise me? No, America in the early 1930s was far more market-oriented than Greece. I’m not surprised that a monetary shock in Greece that was much smaller than in America can produce Great Depression levels of unemployment in Greece. BTW, interwar price indices were much more weighted toward flexible price goods like food and manufactured goods—not services.

There are many other problems with inflation. The bottom line is that it’s not a well-defined variable, and there is no reason to expect it to be a good indicator of demand conditions in an economy. For that you need NGDP.

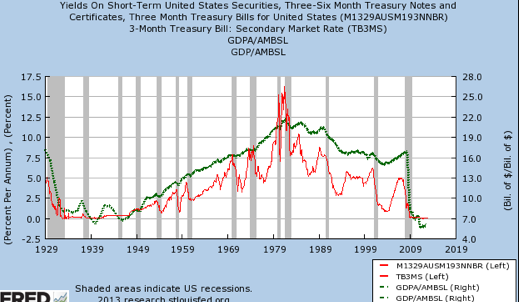

PPS. Earlier I posted on the relationship between interest rates and velocity. Michael Darda sent me a better graph: