It’s widely known that governments in rich countries spend much more than governments in poor countries, even as a share of GDP. There are a number of possible explanations of this pattern. Perhaps rich countries choose to consume more government services, such as education, health care and pensions. Or maybe it’s hard to extract a lot of tax revenue in poor countries where corruption in endemic and many people are peasant farmers or unregistered small businesses. (The fact that the least corrupt rich countries (the Nordics) are especially adept at collecting tax revenue is suggestive.)

Today I’m going to look at a different question; what is the relationship between government spending and wealth among rich countries?

First I’ll list countries in order of government spending as a share of GDP. My sample includes all countries richer that the EU average (which is $31,673 per capita GDP (PPP) in 2011:

[Update: Commenter JN sent me data that is 2 years newer–I put it in parentheses. Most numbers are higher–reflecting the recession? Big swings like Ireland and Iceland might reflect the different timing of big bailouts. Take either series with a grain of salt.]

1. Singapore 17.0% (17.0%)

2. Taiwan 18.5% (22.4%)

3. Hong Kong 18.6% (19.2%)

4. UAE 26.4% (22.3%)

5. Qatar 27.0% (25.1%)

6. Kuwait 31.8% (35.8%)

7. Switzerland 32.0% (34.7%)

8. Australia 34.3% (35.2%)

9. Japan 37.1% (42.8%)

10. Luxembourg 37.2% (42.0%)

11. USA 38.9% (41.7%)

12. Canada 39.7% (42.9%)

13. Norway 40.2% (44.6%)

14. Ireland 42.0% (48.7%)

15. Germany 43.7% (45.7%)

16. Netherlands 45.9% (50.1%)

17. Britain 47.3% (49.2%)

18. Austria 49.0% (50.5%)

19. Finland 49.5% (54.1%)

20. Belgium 50.0% (53.4%)

21. Denmark 51.8% (56.0%)

22. Sweden 52.5% (51.3%)

23. France 52.8% (56.1%)

24. Iceland 57.8% (46.1%)

And here’s a list of the countries in order of income per capita (PPP, IMF)

1. Qatar

2. Luxembourg

3. Singapore

4. Norway

5. Hong Kong

6. United States

7. UAE

8. Switzerland

9. Netherlands

10. Kuwait

11. Austria

12. Australia

13. Ireland

14. Sweden

15. Canada

16. Germany

17. Iceland

18. Belgium

19. Taiwan

20. Denmark

21. Britain

22. Finland

23. France

24. Japan

A few observations:

1. Germany is a fairly typical rich European Country. Of the 15 countries richer than Germany, only three have larger governments (Austria, Netherlands, Sweden). Of the 8 countries poorer than Germany, only two have smaller governments (Taiwan, Japan.)

2. It appears that among the very rich countries of the world, the correlation between per capita GDP and size of government reverses. I can’t be certain, but I think this is even true if you exclude the 4 petro-states (Norway, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait.)

3. Part of this reversal may be due to wealth causing less government spending. Once the basic services are provided, a gusher of oil wealth leads to more non-government consumption.

4. Part of this reversal may be due to high taxes reducing work effort. Many of the richest countries (excluding petro-states?) have both lower taxes and longer working hours.

5. What are we to make of the exceptions?

a. Some rich countries have policies that encourage female employment, despite high taxes. Sweden doesn’t have a marriage penalty discouraging wives from working, for instance, and provides lots of childcare. Others have quite market-friendly policies, despite the big government. This is especially true of the Nordics. Thgis might explain their relatively high productivity, despite high taxes.

b. One country on the list is arguably still developing. Taiwan will likely move into the richer group over time. Its relatively low level of income does not reflect a lack of work effort, but rather low productivity.

c. Japan is the real puzzle here. Like Taiwan, hours worked are pretty long, much higher than Western Europe. This suggests the Japanese workers are extraordinarily unproductive. Some might point to low female labor force participation. But that just means that Japanese females are very unproductive. You could argue that they are at home taking care of the chilren, except that they aren’t having any children.

6. This reversal of correlation at the top end often shows up in comparisons of similar neighbors. The US is richer than Canada, and has a slightly smaller government. Australia is richer than New Zealand, and has a significantly smaller government. Switzerland is richer than Austria, and has a smaller government. Norway is the richest of the Nordics, and has the smallest government. Belgium is ethnically part French and part Dutch, and both its size of government and its wealth is midway between the two. Spain is richer than Portugal and has a smaller government.

7. The East Asian rich tend to have small governments. South Korea was a bit too poor to make the list, but its government spends only 30% of GDP. It will be on the list quite soon. This pattern has huge implications for where the world’s biggest economy (no, not the US anymore) will end up on the list.

8. I predict that within a few decades the US will no longer be regarded as an outlier. It will no longer be regarded as a very rich country with a surprisingly small government.

9. Clinton said the era of big government is over. Obama seems determined to prove Clinton wrong. (Don’t ya just love it when progressives insist Obama is a centrist. Yes, he’s right in the center of progressivism.) This data has support for both sides. It shows that a country can be fairly rich, and still have a very large government. But it also suggests that if Obama pushes the size of government substantially higher, there may be a price to pay. We’ll still be rich, but not as rich. More like France than Switzerland or Norway. I’m not sure how voters would react to that outcome.

10. Sweden’s government is vastly larger than the Swiss government, and yet from an American perspective the two countries seem quite similar. Do both liberals and conservatives overrate the importance of big government? I.e. are conservatives wrong that it would wreck the economy, and are liberals wrong that lots more government spending would greatly improve quality of life? If so, why isn’t Switzerland a hellhole, and why isn’t Sweden poor?

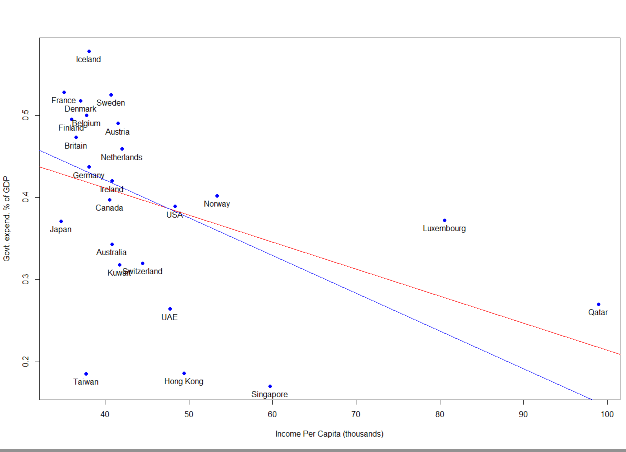

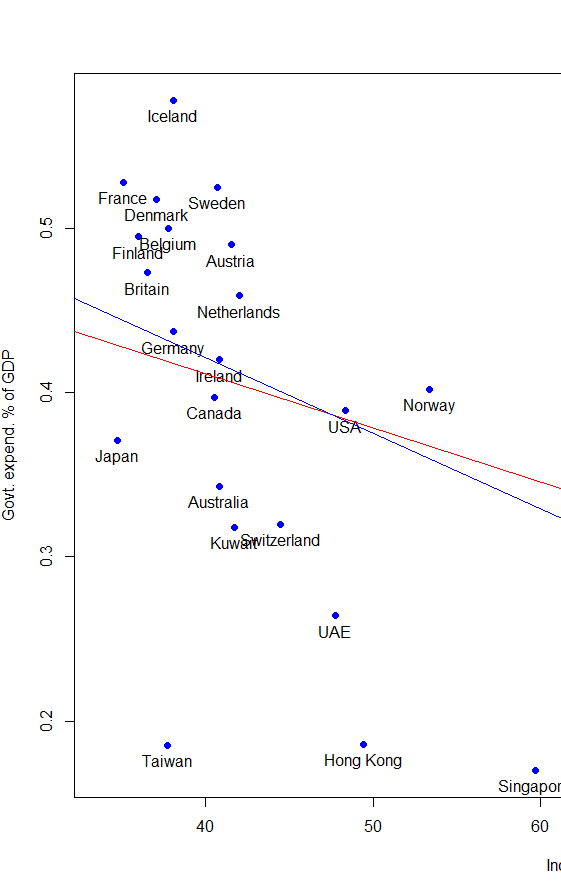

Overall I don’t know if the sample is big enough to be statistically significant, especially without the petro-states. Taiwan would have a big impact–so maybe the results will be different in ten years. If anyone wants to do a regression and/or graph, I’ll add it to the post. If you could find data for government spending and hours worked, the correlation might even be stronger than for wealth.

PS. I could not find size of government data for San Marino and Brunei, which is probably just as well.

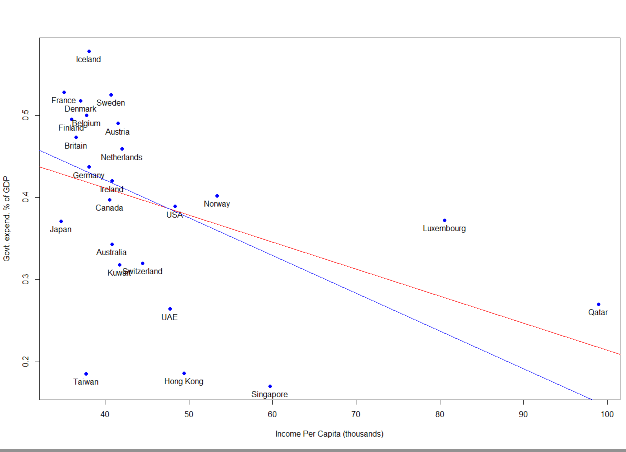

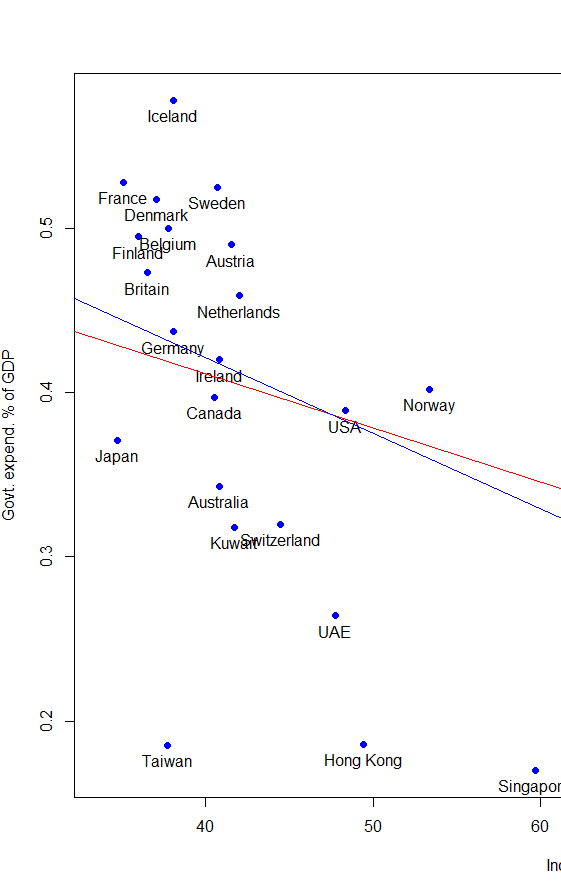

Update: Christopher Burgoyne sent me some graphs with trend lines. The blue line is without the petro-states and the red line is with them included. Even the without is distorted by Luxembourg. But if you look at the core countries and leave out the tiny outliers, it still looks slightly downward sloping to me.