Did the government cause the Great Depression?

A while back some commenters asked me to respond to this claim by Brad DeLong:

Back then, the Friedmans made three powerful factual claims about how the world works – claims that seemed true or maybe true or at least arguably true at the time, but that now seem to be pretty clearly false. Their case for small-government libertarianism rested largely on those claims, and has now largely crumbled, because the world, it turned out, disagreed with them about how it works.

The first claim was that macroeconomic distress is caused by the government, not by the unstable private market, or, rather, that the form of macroeconomic regulation required to produce economic stability is straightforward and easily achieved.

The Friedmans almost always made the claim in its first form: they said that the government had “caused” the Great Depression. But when you dug into their argument, it turned out that what they really meant was the second: whenever private-market instability threatened to cause a depression, the government could avert it or produce a rapid recovery simply by purchasing enough bonds for cash to flood the economy with liquidity.

In other words, the strategic government intervention needed to ensure macroeconomic stability was not only straightforward, but also minimal: the authorities need only manage a steady rate of money-supply growth. The aggressive and comprehensive intervention that Keynesians claimed was needed to manage aggregate demand, and that Minskyites claimed was needed to manage financial risk, was entirely unwarranted.

DeLong makes a plausible case for all three of his assertions. However in the end I still believe it’s reasonable to blame the government for both the Great Depression and our more recent Little Depression. To keep the post from being overly long, I’ll skip over policies that delayed recovery, such as the NIRA, and focus on the Great Contraction.

There are an almost infinite number of ways of looking at Fed policy, i.e. what the Fed is “really doing.” This leads to lots of fruitless debates over errors of omission and commission. In 1913 the Fed was set up with the goal of preventing bank panics and providing an elastic currency. They clearly failed at this task in the early 1930s. The real question is whether the sort of failure that occurred provides ammunition for the libertarian worldview. If the Fed would have needed to be much more active than it actually was, that would seem to undercut Milton Friedman’s laissez-faire ideology.

Let’s see how many ways we can blame the Fed:

1. The US was part of an international gold standard regime. Between October 1929 and October 1930 the world’s central banks sharply raised the world gold reserve ratio. The Fed was responsible for nearly 1/2 of that increase. A higher gold ratio is an activist policy (which violates the “rules of the game”), and is highly contractionary. After October 1930 the Fed lowered their gold ratio, but other central banks (in the gold bloc) kept raising them. By this metric the world’s central banks played a huge role in the Great Contraction, but the Fed’s role was mostly limited to the first year.

2. The Fed reduced the monetary base by about 7% between October 1929 and October 1930. That contributed to the initial slump. But after October 1930 the base rose sharply, as the Fed partly (but not fully) accommodated increased currency and reserve demand associated with the banking panics. The decision to not fully accommodate the increased demand for base money is often viewed as an error of omission, and seems to be the major reason why people like DeLong and Krugman argue that Friedman was being disingenuous in arguing the Fed “caused” the Great Depression. Indeed Krugman has doubts as to whether any base increase would have been sufficient.

3. I seem to recall that Friedman also blamed the Fed for mishandling the failure of the Bank of the United States in December 1930. He argued that support systems available in the pre-Fed era might have prevented the banking panic from spreading. Thus the government took the function of banking stabilization away from the private sector and gave it to the Fed. The Fed botched its job, and that fact supports the libertarian worldview. On the other hand there were plenty of banking crises before 1913, so libertarians can’t really argue that the banking panics would not have occurred if the Fed hadn’t been created.

4. I think the strongest argument against the government is based on the instability of policy. Austrians point out that the Fed propped up the economy in the 1920s, with an activist monetary policy under the leadership of Governor Strong. In fact, monetary policy wasn’t particularly expansionary during the 1920s, using any reasonable metric. But they are right that Strong “fine-tuned” the economy. He argued that the Fed should try to smooth out fluctuations in output in prices—in other words he was a proto-market monetarist. The private sector made all sorts of decisions based on the expectation that Strong’s approach would continue on into the 1930s. But fine-tuning was abandoned in 1929, as the Fed shifted its focus to the stock market bubble. This sudden policy switch triggered the Great Contraction.

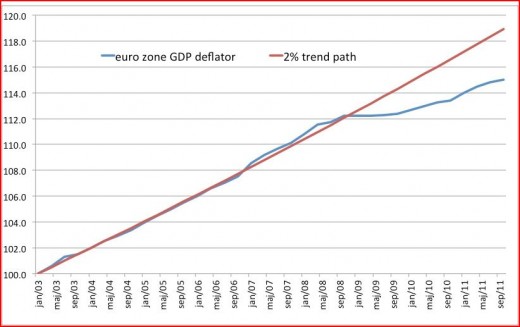

In the end, we don’t really know what a laissez-faire monetary regime would look like in a modern economy, so it’s fruitless to debate that counter-factual. The Fed has been given the duty of managing monetary policy, and the question we should be examining is how much of the instability in RGDP is due to flawed Fed policy. In my view the answer is “most of it.” The overwhelming majority of the business cycle is due to demand shocks, fluctuations in NGDP. (I’d guess that DeLong and Krugman would agree with me there.) I’d also argue that the Fed can and should eliminate most of that NGDP instability. It’s failure to do so makes it mostly responsible for the Great Depression and the Little Depression. But this view doesn’t necessarily provide aid and comfort to libertarians, as it’s quite possible that the business cycle can only be smoothed by putting the best and the brightest into a government-run institution, and then instructing them to steer the nominal economy. That sounds pretty interventionist.

Because I’m a pragmatic libertarian I don’t worry about these sorts of distinctions. In my view the ideal government would be small relative to existing real world governments, but large relative to the laissez-faire ideal visualized by the more dogmatic libertarians. By ‘dogmatic’ I mean those who believe libertarianism provides answers to questions. People who believe you start any analysis with the presumption that the libertarian position is right, and then look for arguments to buttress your case.

In contrast, I believe economic analysis provides answers, and it just so happens that many of those answers line up with the small government agenda. For instance I favor having the Fed stabilize the price of NGDP futures because it would make NGDP more stable than under a discretionary regime. It would also take the Fed out of the business of determining interest rates and/or the money supply, but that’s an implication of the policy, not an argument for the policy.

Prior to Friedman and Schwartz the conventional view was that you needed big government to prevent a repeat of the Great Depression. Friedman convinced the profession that small government plus an effective Fed could do the job. That opened the door to the neoliberal policy revolution, which began in the late 1970s. A little bit of ground has been lost in the current recession, but Friedman’s basic argument still stands.