Joe Stiglitz has a new article, where he continues to develop his rather unconventional view of business cycles. Is his theory a real theory or a demand side theory? I can’t quite tell, maybe one of my commenters can help me out.

Of course the most important stylized fact of the Great Depression was the horrific collapse in industrial production between 1929 and 1933. And what caused this collapse? Apparently productivity improvements in the farm sector. Productivity gains that were also occurring in the booming 1920s.

And how does Stiglitz know this?

At the beginning of the Depression, more than a fifth of all Americans worked on farms. Between 1929 and 1932, these people saw their incomes cut by somewhere between one-third and two-thirds, compounding problems that farmers had faced for years. Agriculture had been a victim of its own success. In 1900, it took a large portion of the U.S. population to produce enough food for the country as a whole. Then came a revolution in agriculture that would gain pace throughout the century””better seeds, better fertilizer, better farming practices, along with widespread mechanization. Today, 2 percent of Americans produce more food than we can consume.

Interesting, but this has been going on for 120 years. So why was the economy booming in 1929, and flat on its back in 1932? And why doesn’t Stiglitz discuss what happened to the incomes for the other 80%, the people not in farming? It turns out that their incomes also fell “between one-third and two-thirds,” indeed nearly 50% by the fourth quarter of 1932. So nothing particularly interesting was going on in farming, and yet this somehow explains the far greater collapse in output in manufacturing, mining, and construction. There may be a model there, but I don’t see it.

What about the conventional explanation, that it was an adverse demand shock? The view that errors of omission or commission by the Fed explain the 50% fall in NGDP:

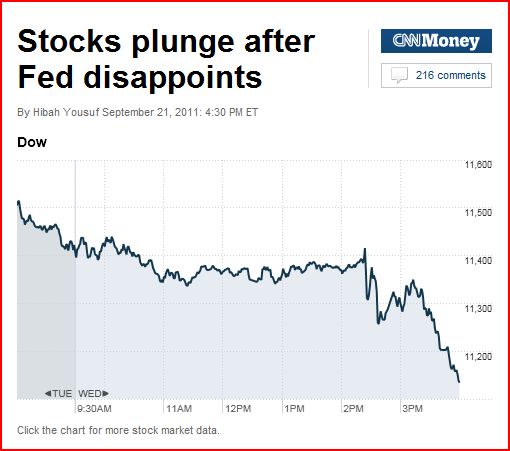

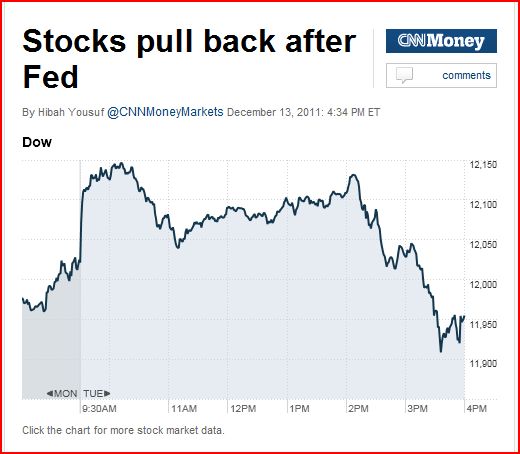

Many have argued that the Depression was caused primarily by excessive tightening of the money supply on the part of the Federal Reserve Board. Ben Bernanke, a scholar of the Depression, has stated publicly that this was the lesson he took away, and the reason he opened the monetary spigots. He opened them very wide. Beginning in 2008, the balance sheet of the Fed doubled and then rose to three times its earlier level. Today it is $2.8 trillion. While the Fed, by doing this, may have succeeded in saving the banks, it didn’t succeed in saving the economy. Reality has not only discredited the Fed but also raised questions about one of the conventional interpretations of the origins of the Depression. The argument has been made that the Fed caused the Depression by tightening money, and if only the Fed back then had increased the money supply””in other words, had done what the Fed has done today””a full-blown Depression would likely have been averted. In economics, it’s difficult to test hypotheses with controlled experiments of the kind the hard sciences can conduct. But the inability of the monetary expansion to counteract this current recession should forever lay to rest the idea that monetary policy was the prime culprit in the 1930s.

. . .

Monetary policy is not going to help us out of this mess. Ben Bernanke has, belatedly, admitted as much.

Readers of Vanity Fair are being led to believe that Bernanke went into this downturn thinking that monetary stimulus was the answer to depressions, and then had a sort of epiphany that monetary stimulus doesn’t work. Is this really true? Has Bernanke suddenly become an adherent to the view that the Fed is out of ammunition? Or that they have ammo, but that nominal growth can’t solve real problems (as RBC adherents believe.) I’ll pay $100 to the first person who can convince me that Bernanke believes monetary policy can’t boost AD, or that he believes AD can’t boost output. (I should offer $10,000, but proportional to wealth my offer is just as generous as Mitt Romney’s.)

Stiglitz is a distinguished Nobel Prize winner. But he didn’t win for business cycle theory. I doubt even his fellow progressive Paul Krugman could make heads or tails out of Stiglitz’s essay. That doesn’t make Stiglitz wrong (I’m also a contrarian.) But if you are going to make that sort of argument, you need more evidence than farm incomes falling during the Great Depression.

Paul Krugman likes to show a graph indicating that each country began recovering from the Depression right after it adopted expansionary monetary policies (i.e. currency devaluation.) If Stiglitz has an explanation for that, I’d love to hear it.

Back in the 1930s many people thought the Great Depression was caused by too much output. This led FDR to adopt programs aimed at reducing output (such as the AAA and the NIRA.) They “worked.” Today economists tend to scoff at such ideas, as falling output is essentially the definition of a depression. But not Stiglitz:

Throughout the 1930s, in spite of the massive drop in farm income, there was little overall out-migration. Meanwhile, the farmers continued to produce, sometimes working even harder to make up for lower prices. Individually, that made sense; collectively, it didn’t, as any increased output kept forcing prices down.

HT: Gregory Barr, Larry

Update: I see Ryan Avent is equally puzzled by Stiglitz’s model. And so is Nick Rowe. Will Krugman give Stiglitz the Fama/Lucas/Cochrane treatment?