Are there any non-QTM explanations of the price level?

This is sort of a response to some Keynesian/fiscal theory/Post Keynesian/MMT theories I’ve seen floating around on the internet. Theories that deny open market purchases are inflationary, because you are just exchanging one form of government debt for another. But first a few qualifiers:

1. If the new base money is interest-bearing reserves, I fully agree that OMOs may not be inflationary. That’s exchanging one type of debt for another. If it does raise inflation expectations (as QE2 did) it’s probably because it changed expectations of future monetary policy.

2. If nominal rates are near zero, the situation is complex–I’ll return to that case later.

So let’s start with an economy that has “normal” (i.e. non-zero) interest rates, and non-interest-bearing base money. How does the price level get determined in that case? I’m told there are some theories of fiat money that suggest it must evolve from commodity money. I don’t agree. I think the quantity theory of money is all we need. Suppose you dump 300,000 Europeans on an uninhabited island—call it Iceland. The ship also drops off some crates of Monopoly money, and they’re told to use it as currency. Assume no growth for simplicity. Also assume no government and no banking system. It’s likely that NGDP will end up being roughly 15 to 50 times the value of the stock of currency. Once you pin down NGDP, then you figure out RGDP using real growth theories, and voila, you’ve got the price level. At this point you might be thinking; “you consider ’15 to 50 times the currency stock’ to be a precise scientific solution?” No, but it gets us in the ball park. It tells us why prices are not 100 times higher than they are, or 1000 times higher. BTW, prices in Japan are 100 times higher than in the US, and Korean prices are 1000 times higher. I don’t see how other theories can even get us into the right ball park.

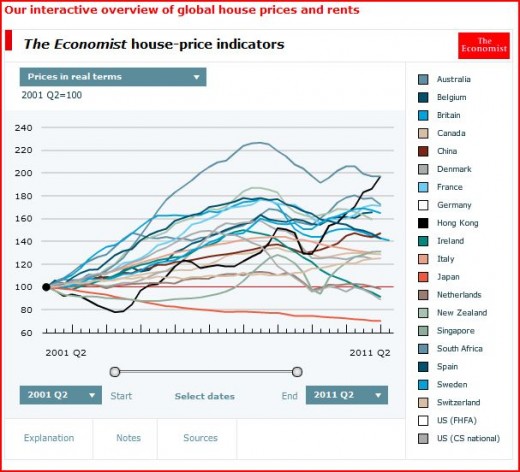

I’m going to illustrate the problem of non-QTM theories of the price level with a comparison of the US Australia and Canada. Here are some national debt figures from The Economist:

For simplicity assume Australia’s net debt was zero in 2007. In Australia NGDP is about 30 times the currency stock. Canada is similar. (The US NGDP was only about 18 times the currency stock in 2007, because lots of our currency is hoarded overseas.) This ratio is determined by the public. The base also includes reserves, but in normal times like 2007 we can ignore those if we aren’t paying interest on reserves. The opportunity cost of holding reserves is simply too large for banks to want to hold very much. So the central bank determines the nominal base, and the public determines the ratio of NGDP to the base (aka velocity.)

Because Australia and Canada are fairly similar countries, I can get a reasonable estimate of each country’s price level as follows:

1. Notice that their RGDP per capita is similar.

2. Find the NGDP in one country (say Canada.)

3. Find the currency stock in each country.

4. Assume their NGDP/currency ratios are similar (roughly 30.)

Then all I need is Australia’s currency stock to estimate the price level in Australia. Now suppose it was true that OMOs didn’t matter. In that case the aggregates that would be important would be the entire stock of government liabilities, currency plus debt. But as you can see, Canada’s was many times larger than Australia’s. (Recall that in both countries currency is only about 3% to 4% of NGDP.) If you looked at total government liabilities you’d get nonsense, you’d estimate Canada’s price level in 2007 to be between 5 and 10 times that of Australia, as its debt was 23.4% of GDP (so debt plus base was about 27% of GDP), vs. about 3% to 4% in Australia. The base is “high-powered money” and interest-bearing debt isn’t. Demand for Australian cash is very limited; you just need a little bit to smooth transactions in Australia. Double it and the value of each note falls in half. Double the amount of Australian T-bonds, and it’s just a drop in the bucket of a huge global market for interest-bearing debt. The value of those bonds changes hardly at all.

Now suppose that in 2007 the US monetized the entire net debt, exchanging $6 trillion in non-interest bearing base money for T-securities. And suppose this action is permanent. The monetary base would have increased about 8-fold, and the QTM tells us the US NGDP (and price level) would also have increased 8-fold. In that case our situation will be much like that of Australia; we’d have a monetary base, but no interest-bearing national debt. So our price level would be determined in the same way Australia’s price level is determined. NGDP would be some multiple of the base, depending on the public’s preference to hold currency (including foreign holdings of US currency.) But since our base (and currency stock) went up 8-fold, if the ratio of NGDP to currency remained around 18, then the level of NGDP would also increase 8-fold. That shows OMOs do matter, at least if I’m right about the public’s demand for currency usually being some fairly predictable share of NGDP.

Here’s my problem with all non-QTM models. Suppose I’m right that only the QTM can explain the current price level. Then it stands to reason that only the QTM can explain the price level in 2021. Then it stands to reason that only the QTM can explain the inflation rate between 2011 and 2021. Now it is true that a change in the money supply will have certain effects on nominal interest rates, economic slack, etc, depending on whether the monetary injections were expected or not. And you can try to model the inflation rate using those changes in interest rates, economic slack, inflation expectations, etc. But that’s really a roundabout way of getting at the problem. If the QTM says that the price level in 2012 will be 47% higher due to changes in the monetary base, plus changes in the public’s desire to hold currency as a ratio or NGDP, then either the non-QTM approaches also give you the 47% answer, or they are wrong.

Here’s a nautical analogy. You can estimate how fast a cigarette boat was going by looking at the size of the engine, the throttle setting, and so on. That’s the direct approach, the engine drives the boat. Or you can estimate its speed by how big its side effects were (the size of the wake, how loudly seagulls screeched as they got out of the way, etc.) The engine approach is the QTM. That’s what drives inflation. (God I hope at least Nick gets this, otherwise I’ve totally failed.) The Keynesian approach is to look at epiphenomena (like interest rates and slack) that may occur because wages and prices may be sticky to some unknown extent. It’s like looking at the wake and trying to estimate what sort of boat went by.

OK, what about at the zero bound, aren’t cash and T-securities perfect substitutes? Maybe, but if they aren’t expected to be perfect substitutes in 2021, then a current OMO that is expected to be permanent will have the same impact on the expected long run price level as an OMO occurring when T-bill yields are 4%.

Of course central banks don’t target the base, they adjust the base until short term interest rates are at a level expected to produce the right inflation rate. It’d be like adjusting the throttle until the wake looks about the right size to hit the target speed. And in the future they might go even further away from money supply control, if they pay interest on reserves. In that case they’ll be adjusting rates and the base in a more complicated pattern, both money supply and demand will change. But the currency stock will still be non-interest bearing for a while, so that relationship will continue to hold.

What would cause a revival of monetarism? That’s easy. We just need to return to widely varying trend rates of inflation, as we saw in the 1960-1990 period. In those decades countries might have 5%, 10%, 20%, 40% or even 80% trend inflation. As that settles in, and people expect it, the various epiphenomena of unexpected money go away (liquidity effect, slack, etc.) And everyone goes back to explaining inflation by looking at growth in the non-interest bearing monetary stock. It’s the only way. The best example was in the hyperinflationary early 1920s, when even Wicksell and Keynes, the two great proponents of the interest rate approach, became quasi-monetarists. Needless to say I have very mixed feelings about the prospect of a revival of monetarism.

So here’s my question: Are there any non-quantity theoretic models of the price level? Theories that could explain the difference between Australian and Canadian and Japanese and Korean price levels?