Think NGDI, not NGDP

In the standard national income accounting, gross domestic income equals gross domestic output. In the simplest model of all (with no government or trade) you have the following identity:

NGDI = C + S = C + I = NGDP (it also applies to RGDI and RGDP)

Because these two variables are identical, any model that explains one will, ipso facto, explain the other. Nonetheless, I think if we focus on NGDI we are more likely to be able to think clearly about macro issues. Consider the recent comment left by Doug:

Regarding Investment, changes in private investment are the single biggest dynamic in the business cycle. While I may be 1/4 the size of C in terms of the contribution to spending, it is 6x more volatile. The economy doesn’t slip into recession because of a fluctuation in Consumption. Changes in Investment drive AD.

This is probably how most people look at things, but in my view it’s highly misleading. Monetary policy drives AD, and AD drives investment. This is easier to explain if we think in terms of NGDI, not NGDP. Tight money reduces NGDI. That means the sum of nominal consumption and nominal saving must fall, by the amount that NGDI declines. What about real income? If wages are sticky, then as NGDI declines, hours worked will fall, and real income will decline.

So far we have no reason to assume that C or S will fall at a different rate than NGDI. But if real income falls for temporary reasons (the business cycle), then the public will typically smooth consumption. Thus if NGDP falls by 4%, consumption might fall by 2% while saving might fall by something like 10%. This is a prediction of the permanent income hypothesis. And of course if saving falls much more sharply than gross income, investment will also decline sharply, because savings is exactly equal to investment.

[Update: Lorenzo directed me to an excellent post by Andy Harless, explaining why S=I.]

This is where Keynesian economics has caused endless confusion. Keynesians don’t deny that (ex post) less saving leads to less investment, but they think this claim is misleading, because (they claim) an attempt by the public to save less will boost NGDP, and this will lead to more investment (and more realized saving.) In their model when the public attempts to save less (ex ante), it may well end up saving more (ex post.)

The Keynesian model probably works best in a gold standard world. An attempt to save more will depress nominal interest rates. If the stock of gold is approximately fixed in the short run, then the lower nominal interest rates will boost the demand for gold, and increase the value of gold. If gold is the medium of account then this will be deflationary. NGDI will decline, and if wages and prices are sticky this will ultimately lead to less saving and less investment. So there is a grain of truth in the Keynesian model, if you are in a gold standard world (as Keynes was when he developed the model.)

But we no longer live in a gold standard world, and today it makes more sense to view NGDI (and NGDP) as being determined by the central bank. In that world monetary shocks create (or worsen) investment volatility.

Here’s another example. Recent posts by Simon Wren-Lewis and Nick Rowe criticize new Keynesian models that feature a sort of “divine coincidence.” In these models (assuming Calvo pricing) when the central bank stabilizes inflation it also keeps output at potential. They kill two birds with one stone—price stability and no output gaps. This result follows from the NGDP (expenditure) approach–focusing on sticky prices and aggregate purchases of consumption and investment goods.

Both Wren-Lewis and Rowe rightly point out that these models did poorly in the Great Recession. Nick wants to shift to NGDP targeting (as do I.) But it might be easier to explain the advantages with the NGDI approach. Unlike the sticky-price NK model, the “musical chairs model” did beautifully during the Great Recession. In this model, when there is a sudden fall in NGDI, there is less income to allocate to workers. Because hourly wages are extremely sticky, this means many fewer hours worked. If the major central banks had kept inflation stable during the Great Recession, it probably would have been a bit milder, but we still might have experienced a pretty big recession.

In contrast, a stable path of NGDI would have led to fairly stable hours worked (unless hourly wages did something truly bizarre in response.) What about the Lucas Critique? If it applies at all (and I’m not sure it does), then I’d guess workers would respond to NGDI targeting with even stickier wages. Output gaps would probably be much smaller, but might be longer lasting. Indeed it’s quite possible that the “Great Moderation,” which produced results not too unlike NGDP targeting, has already made wages a bit stickier (especially when compared to the 1865-1929 period.) If so, that’s a price I am more than willing to pay.

PS. We finally succeeded in embedding the NGDP futures price at Hypermind in the right column of this blog. Please look for it when you tune in each day. And trade some contracts—you can win but you can’t lose. The specific price shown (about 4.2% last time I checked) is for 2014:Q4 to 2015:Q4.

The iPredict market is still progressing, but these things always take longer than I expect. It took us several weeks just to get the NGDP price embedded.

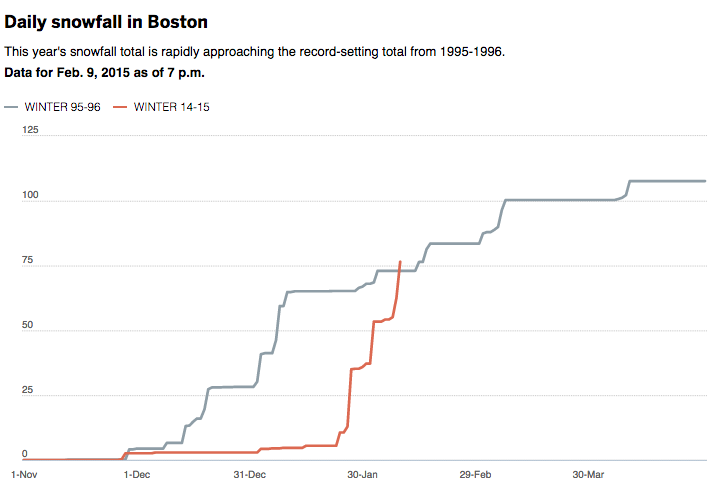

PPS. The winter from hell continues. Boston has gotten about 70 inches of snow in the past 17 days. Before that we had only gotten 5.5 inches all winter. In 17 days we’ve gone from a winter with almost no snow, to the 10th snowiest ever. And there are two months to go, with more snow on the way. To put that 70 inches in 17 days into perspective, the previous record was 31 inches in a week. So it’s roughly like we had 2 1/2 weeks in a row of snow intensity at the level of the very worst week in all of Boston history. A stock market analogy would be 17 days of decline at the rate of the worst week in NYSE history. Ouch.

If you start to see me endlessly typing:

All work and no play . . .

Or:

Here’s Scottie!

You’ll know that cabin fever has set in. Schools are closed as often then they are open, 6 days missed in the past 2 1/2 weeks.

Probably shouldn’t have watched Twin Peaks with my teenage daughter—definitely won’t be renting The Shining.

Tags:

9. February 2015 at 18:18

I think you’re guilty of downplaying the importance of the private sector.

In this case, even when it’s pointed out that private investment has driven the recovery, you attempt to credit this to actions by the central bank or monetary policy.

Simply put, when the private sector believes it has good investment opportunities, it will go to the banks for capital, no matter what the monetary policy of the day looks like.

…

Also, we have to define savings and investments are different animals and not the same thing. If I take my excess savings and buy a financial asset like a stock or a certificate of deposit or a painting or gold, then I am saving. If I take my excess savings and buy labor or inventory or marketing for my business, then I am investing. In the latter case, you are using your money to produce economic activity. I know that’s hard to break down to accurate numbers, but what we want are investments and not savings so we have to measure it so we can monitor and encourage investments.

9. February 2015 at 18:48

Charlie Jamieson: “Simply put, when the private sector believes it has good investment opportunities, it will go to the banks for capital, no matter what the monetary policy of the day looks like.” Ah, a man of the concrete steppes. In aggregate will not investment opportunities have something to do with income expectations? And those have a great deal to do with monetary policy.

Or do you think Australia, for example, has just been magically blessed with 22 years of better investment opportunities?

As for your second para, this Andy Harless post might be helpful to clarify matters:

http://blog.andyharless.com/2009/11/investment-makes-saving-possible.html

9. February 2015 at 19:05

Charlie, You said:

“I think you’re guilty of downplaying the importance of the private sector.

In this case, even when it’s pointed out that private investment has driven the recovery, you attempt to credit this to actions by the central bank or monetary policy.”

Actually, we agree more than you think. The private sector drove the recovery with no help from the Fed. I may create the opposite impression by pointing out that Fed policy has been much more expansionary than ECB policy. But I’d say Fed policy basically did little to help or hinder, whereas ECB policy slowed their recovery. So yes, the private sector drives growth in the US. I’m fine with that view.

Lorenzo points to Australia, which had what I’d view as fairly neutral policy throughout the entire Great Recession. The US had worse, and the ECB even worse. Ideal monetary policy just gets money out of the picture, and let’s the private sector get on with things.

Thanks Lorenzo, I’ll take a look.

9. February 2015 at 19:11

“This is probably how most people look at things, but in my view it’s highly misleading. Monetary policy drives AD, and AD drives investment.”

Logically and temporally, investment drives AD, not vice versa.

In order for there to be spending on output, someone somewhere must have produced that output, and the production of output requires investment.

If a central bank is going to target NGDP, it is not true that higher NGDP drives higher investment. It might, but it is not necessarily so, as higher NGDP may be the RESULT of unchanged investment and higher consumption spending.

Investment logically and temporally precedes consumption.

If NGDP is going to go up, then it MUST be the case that it goes up via higher consumption and/or higher investment spending.

“This is easier to explain if we think in terms of NGDI, not NGDP. Tight money reduces NGDI. That means the sum of nominal consumption and nominal saving must fall, by the amount that NGDI declines.”

That is misleading. Tight money reduces investment and/or consumption spending, and THAT reduction in investment and/or consumption spending is what we know to be a reduction in NGDI.

It is easier and more clear to understand NGDP and NGDI as outcomes, as summations, as a mathematical collection of individual investment and consumption expenditures.

If a central bank reduces the extent to which it inflates the money supply, such that those who both take ownership of that new money, and/or those who already have money from previous inflation that was spend and respent from previous parties, decide to hold onto their money earnings a little longer than before, such that NGDP and NGDI falls, then what has happened is not that the central bank mind controlled everyone into spending less on aggregate output (C + I). No, they altered the money relation and then others spent less or more than they otherwise might have spent. Those individual reductions in spending are what we know to be reductions in NGDP and NGDI.

“What about real income? If wages are sticky, then as NGDI declines, hours worked will fall, and real income will decline.”

This is also misleading. While it may be true that a fall in aggregate spending may be associated with a concomitant reduction in the output of existing work and production processes, it is not where the story ends. There is a reason why people reduced their spending. It is not simply a matter of central banks not printing enough so as to prevent NGDI/NGDP from falling. That is just looking at the symptoms. We also should consider why it is that people reduced their spending.

No, it is not simply a matter of them wanting more money with absolutely no change to work and production processes. They also want a change to the work and production processes. If they didn’t, then they would have gone ahead and spent out of their existing cash balances on that output instead of cash hoarding, which then reduces NGDI, which you crudely view as nothing but a failure of the central bank in raising NGDI.

When NGDI declines, then unless the central bank has sent drones to burn up piles of money and destroy banks with money balance information, there is something more going on in the population to make them want to reduce their spending on existing output. Something in the existing production processes must change.

—————-

“So far we have no reason to assume that C or S will fall at a different rate than NGDI.”

Absolutely false. There is no excuse for you to say such a thing, not when you have FREE access to a cornucopia of literature that explains in great detail why it is that investment tends to fall much further than consumption during recessions that are accompanied by a reduction in total spending.

No reason to expect it? BAH! If capital structure economics are taken into account, there is a very good reason to expect it.

Doug touched on an important point about the relative volatility between investment and consumption, which was totally dismissed and handwaved at as if it doesn’t exist.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=10gn

This is a chart of investment change YoY and consumption YoY.

As far back as the data for personal consumption expenditures goes (~1960), we can see that investment has always been more volatile than consumption spending, both during recessions and during booms.

For those who are not intellectually invested in putting one’s head in the sand, investment is more volatile than consumption because it is investments that contain the most calculation errors as a result of central banking.

As a rule – and there are exceptions – inflation from the central bank results in increased “spending” primarily through net investment. Money leaves the banks in the the form of loans to finance existing businesses, and new businesses. Think materials, machinery, labor, rent, B2B services, and so on. This is more or less persistent. By the time this increased net investment spending is followed by increased consumption (from higher wage payments, dividends, and interest payments to debt holders), there is already another round of increased net investment from inflation.

But all the way through, inflation is having the largest promixite effect on net investment. This is why during inflationary booms we tend to see dramatic rises in that which investment finances (stocks, bonds, assets), and why deflationary recessions we tend to see dramatic declines in the same.

Sometimes we see “consumption booms”. This occurs when inflation from the central banking system is significantly in the form of consumer loans. But most of the time, we see investment booms and busts.

NGDP rises by way of higher investment and/or higher consumption that comes out of a higher money supply. It is not correct to first ask what the outcome was, and then ask OK, what was this outcome’s effect on its components of investment and consumption.

Vulgar aggregation minded thinking literally stunts one’s ability to understand what is going on in the economy. Don’t start with outcomes. Start with what the outcomes are composed of, and then understand the outcomes to be a conglomeration of inputs.

9. February 2015 at 19:48

Aside from the valid criticisms by Charlie Jamieson and MF, I am puzzled by this Sumner post. What is the purpose? The only thing I could think of is, yet again, Sumner plans to change from targeting NGDP to targeting NGDI. Are we to trust this unstable man with the nation’s money supply, when he changes plans week to week? Blame it on cabin fever.

9. February 2015 at 20:02

“because savings is exactly equal to investment.”

No its not. You can import investment dollars.

And, you can have a declining savings rate and an investment boom. see the 1990’s.

“Monetary policy drives AD, and AD drives investment.”

Almost. Tomorrow’s AD drives today’s investment.

9. February 2015 at 21:44

mf

it’s amazing how much pointless effort people will put into attempting to justify their irrational fetish for shiny objects and their desire to extract risk-free rents from other people’s work.

9. February 2015 at 23:25

Exactly how are you defining I?

10. February 2015 at 00:17

I think Sumner is defining savings as “global savings”, since as Doug M says, you can import the savings of Chinese workers (and the USA has).

OT – Look at history and how fooling with money, as Sumner proposes, leads to folly (and in fact lead to the Great Depression, if you believe in the monetarists).

A plea from Comptroller Williams of the US Fed to US President Harding, in January 13, 1921, to change Fed policy from doing nothing and letting gold do its work, which was a sound policy (that worked in 1921) to an activist policy of stable prices, to be administered by the Fed chairman (which was not adopted until ten years later, with disastrous consequences). Harding’s reply to Williams:

“And as for Williams’s suggestion that the Federal Reserve replace the tried and true with the new and untested, why, Harding replied, he and the rest of the board would decline it, “especially if those new plans and methods are fundamentally unsound.” ”

from Grant, James (2014-11-11). The Forgotten Depression: 1921: The Crash That Cured Itself (p. 113). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

10. February 2015 at 04:04

In a simple economy with no government and no trade, you cannot import saving.

In a world with trade, you must certainly can import saving. Importing saving is a net capital inflow matching a trade deficit.

I really don’t like this approach–too identity dependent.

Lets see…

The central bank chooses to lower nominal income. Hourly wages are sticky, so real output falls. Consumption smoothing (we through in an actual behavioral relationship.) So, saving falls. This could result in less investment or less exports or more imports.

Which is it? I don’t see how the identity helps.

10. February 2015 at 04:42

Philippe:

“it’s amazing how much pointless effort people will put into attempting to justify their irrational fetish for shiny objects and their desire to extract risk-free rents from other people’s work.”

You desire “shiny objects” in the form of government paper.

I desire a free market in money in which the individual decides for themselves what to accept as a highly liquid store of value.

You believe productivity based falling prices creates victims of “rent” exploitation.

I correctly know that belief to be false, and self-contradictory even if we assume it isn’t false. Someone who earns money but does not spend it right away, is providing value to others. They are putting real wealth into the economy but not taking that same amount of real wealth out of the economy as valued by the money. If you knew anything of economics, then you would understand that cash hoarders and misers are actually providing others with net value.

Even if we assume what you said is true, that I am extracting wealth from you by merely holding onto my earnings without initiating any coercion or force against you, and this occurs because prices are falling, then by symmetry if that is exploitative then there must be exploitation in the other direction if prices were instead rising. So what you want must by your own premises be a rent form of exploitation.

Finally, what is actually “amazing” is your mental defectiveness compelling you to see “derp! Gold bugs!” in places it does not even exist. I am a free market in money advocate, not a gold standard advocate. I’ve said this a zillion times but you are clearly mentally incapable or unwilling to be honest. You likely have an oversized amygdala that hampers your cognitive functioning. You likely weren’t breast fed as a baby.

10. February 2015 at 04:53

To clarify what others here already know: If production of goods outpaces the production of money, such that prices fall over time, then the real rate of return that cash “earns” would be equal for everyone. Everyone would earn the same real return on their cash earnings. To call people earning money and then buying goods on a free market a system of “rent” is beyond stupid.

10. February 2015 at 05:54

Monetary policy drives AD, and AD drives investment–Scott Sumner.

Dang right. Business dudes invest when they are pretty sure they can sell what they are producing. I was a business dude.

Sure, some guys take chances, like the Tesla dude. VC money. Wildcatters etc. There are risk-takers—but they are more likely to take risks in a world of growing AD.

First, print a lot more money. Once the house is on fire, and people are lighting up with Ben Franklins, and mini-skirts are back and above the crotch, then maybe start NGDPLT.

But first, Fat City. We need some boom times.

10. February 2015 at 06:04

@Ben Cole – it seems you like cartoons. I have two movies that you will enjoy: Sin City (2005) and Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014). But in the real world, printing money does not work except, arguably, for a few weeks at best (if that). You cannot expect people to spend their way to prosperity 7 years after a financial crash. We don’t have a liquidity crisis anymore, it’s more structural, as in Japan.

10. February 2015 at 06:16

Great post. That framework gives me a clearer and cleaner way of thinking of the shifting variables and their impacts.

Question: Do you differ the impacts of various categories of C? If not mechanically then mentally? I have no data to base this on, but mentally I vary the impacts of different categories of C such as restaurants, retail, durable goods and health care. An extreme example is what if we spent all our money on lottery tickets versus cars versus health care? I dislike thinking in terms of a Keynesian multiplier, but I can’t help thinking that some spending by consumers has better economic impacts (short or long run) than others. Is this baseless?

10. February 2015 at 06:22

bill woolsey:

“So, saving falls. This could result in less investment or less exports or more imports.”

I’d think the answer can’t be the last option. In a scenario of contracting nominal income how and why would imports increase? I’d think a combo of less investment and lower exports would be the answer.

10. February 2015 at 06:39

Can’t help with convincing the entire economics profession that you are right, but I lived the first 30 years of my life in Syracuse and Buffalo where 120 inches is average.

You need this: a good electric snowblower. The gas ones are royal pains because the correlation between conditions where you need a snowblower and conditions that gasoline engines like to start in is quite negative. Get a good low temperature extension cord and you will make short work of even the worst snowstorm.

10. February 2015 at 07:00

I, too, liked Harless’s post. But he isn’t careful enough with his terminology. He says that when you spend money you are dissaving. He should have said “spend money *on consumption goods (or services)*.” Spending money on *investment goods (or services)* is not dissaving.

By the way, the consumption/investment distinction looks fuzzy.

10. February 2015 at 07:25

I still find it hard believe you could be so far off in the boonies that there are no good snow services. If you insist on shoveling, please be sure to take it easy!

The Keynesian model probably works best in a gold standard world.

That’s an interesting point.

10. February 2015 at 07:30

Off topic: I have found the recent posts by Nick Rowe and Roger Farmer vexing:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2015/02/debt-does-have-intergenerational-distributional-implications.html

http://rogerfarmerblog.blogspot.com/2015/02/sam-and-janet-learn-about-debt.html

They both claim that an increase in government debt makes future generations poorer (than they would have been without government debt).

I fundamentally cannot see how this can be, as the primary effect of government debt is to set up future transfers from future taxpayers to future bondholders. This is obviously redistributional, but I don’t see how it makes people living in the future any poorer in aggregate, because every dollar of taxes taken from a future taxpayer is given to a future bond holder, netting to zero. Both Nick and Roger are gracious in responding to my confusion by pointing out how government programs can transfer wealth or consumption across generations. I do not contest that, but I do not see how government debt affects government intergenerational redistribution one way or the other. G could just as well borrow from the old and give to the young, making our children richer and us poorer. The intergenerational transfer effect and the government debt itself seem like separate things.

I’d be curious about Scott’s take on this topic in a future post.

-Ken

10. February 2015 at 07:34

Lorenzo:

You can have investment without savings. And investment can create more consumption or savings or more investment.

First of all, there is some investment that doesn’t require capital or savings. A society that invests in a culture of education and hard work (like South Korea) will create quite a bit of productivity. A many that exercises is making an investment in himself, no capital required.

Second, we can invest using either my savings and/or we can borrow money. Borrowing is a better way.

If I were to invest in a snow shoveling company in Boston, I could go to the bank with my proposition, obtain a loan, and begin hiring young show shovelers. That would create income and savings and possibly even more investment as these young show shovelers strike out on their own.

And remember, banks do not lend me deposits, banks create deposits.

…

Ben is calling for money printing, but what we’re starting to see in the private sector the last couple of years is the end of deleveraging and the private sector is beginnning to ‘print’ money by taking loans. So long as these loans are productive, the economy will grow. If these loans are not productive, as what happened in the 2000s, then we will go into recession again.

It’s up to the central bank to facilitate lending, but generally the Fed responds to the private sector and not the other way around. When the private sector wants to borrow, the Fed supports this, even to an extreme; when the private sector doesn’t want to borrow, the Fed is relatively powerless.

10. February 2015 at 07:42

Ken, I’ll take a stab at that.

Government debt doesn’t have to be paid back. A government bond is an asset in itself; it’s not something that needs to be paid back. If I’m a bond holder and want to exchange it for a deposit, I can do that either in the market or by going to the central bank.

The two factors to consider with government debt are:

a) am I risking inflation by printing too many government bonds?

b) am I spending the money wisely? If you run deficits to help young people educate themselves, they will never have to ‘pay back’ their education. The spending has created something of value. The young wouldn’t mind deficit spending if it went for spending that benefits them — infrastructure, education, public order, etc. But these are political points, not fiscal or monetary.

I guess another factor is interest rates. You don’t want interest payments on the debt to get out of hand.

10. February 2015 at 08:12

Boston snow… that’s hardly more than a flurry. I was in Tokamachi once when they got 119 inches in week.

10. February 2015 at 08:13

Thanks Charlie. I agree that unwise government spending makes us all poorer, but of course it does that immediately, and it also has nothing to do with how the unwise spending was financed (taxes, borrowing from the public, or borrowing from the central bank).

Slightly less off topic, check this out:

http://marketmonetarist.com/2015/02/09/kurodas-new-team-member-yutaka-harada/

It looks like the Bank of Japan is going to be someone who understand the proper role for monetary and fiscal policy, and understands the difference between low rates and loose money. Could be very exciting for Japan. I wonder what he’ll be able to do once he’s actually inside the institution.

-Ken

10. February 2015 at 08:24

Kenneth Duda: “I fundamentally cannot see how this can be, as the primary effect of government debt is to set up future transfers from future taxpayers to future bondholders. This is obviously redistributional, but I don’t see how it makes people living in the future any poorer in aggregate, because every dollar of taxes taken from a future taxpayer is given to a future bond holder, netting to zero.”

There are two key concepts to understand how this happens:

1. Future bondholders may need to PURCHASE the bonds instead of bonds being given to them (inherited) by older generations.

2. Generations overlap. So some future bonholder were given future taxpayer money in exchange of bonds that they themselves purchased from their fathers who purchased them from their father fathers back into present where the bonds were used to finance one-time transfer to present generation.

But really Nick Rowe was there first with much more succint explanation of the key concept here: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/10/how-time-travel-is-possible.html

It is shorter than this post. Go read it. If you do not understand read it again later with fresh eyes and just try to just grasp the simplest and the most distilled concept of how this time travel of milk is possible in OLG scenario. Then you can add as much complications to see if the idea holds (it does).

PS: Scott I am sorry if I am hijacking the discussion I will not contuinue. The blog itself is quite good and I really like Andy Harless’s post. I pointed to it several times myself to drive this simple idea of why S=I through.

10. February 2015 at 08:26

@Kenneth Duda

The fundamental insight is that generations are overlapping. While debt cannot redistribute consumption between years X and Y, fiscal policy can redistribute consumption between generations during specific year X. Nick Rowe has about ten posts about this, but this is the clearest one:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/01/bob-murphy-plays-with-the-debt-burden.html

10. February 2015 at 08:43

The Murphy post is a fun read.

Apples aren’t bonds, of course, and we can’t ‘save’ apples across generations.

We can only organize a society that is able to produce more apples in every generation. As long as we can do that, we can be very careless and very generous.

I will certainly agree to eat less apples so the government can take my apples and give them to somebody else (as long as that person is needy), but Uncle Sam better plant some apple trees or better yet let me do it so my grandchildren can have apples.

Our ability to ‘save’ for the future is limited. We can all throw our savings into Coca Cola and Exxon, but in 30 years if we have war or environmental disaster we won’t be able to eat those stock statements.

10. February 2015 at 08:47

Ray, You said:

“Sumner plans to change from targeting NGDP to targeting NGDI.”

Thanks for making me smile on a snowy morning.

Doug, I’m afraid you are wrong, they are equal by definition. Check out Andy Harless’s post. With trade, you have global saving equal to global investment.

Fed Up, Production of capital goods.

Bill, You said:

“This could result in less investment or less exports or more imports.”

That’s right, I was using a closed economy model to make a simple point. The basic argument applies in an open economy as well, but it’s more complicated, as you say.

Anthony, You said:

“I dislike thinking in terms of a Keynesian multiplier, but I can’t help thinking that some spending by consumers has better economic impacts (short or long run) than others. Is this baseless?”

I’d discourage you from thinking this way, unless there are externalities that are not priced in. Thus consumption of coal might be less useful, as it has negative externalities. But I don’t think you can say services are less useful than non-durable or durable goods.

Njnnja, And where do you suggest I blow the snow?

Philo, Yes, the distinction is very fuzzy.

Ken, Nick has a new post using a food analogy that explains the concept quite well. It’s very counterintuitive and it took me a while before I saw Nick’s point.

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2015/02/how-markets-convert-meat-into-vegetables.html#more

BTW, I did a post on the new BOJ member a few days ago.

JV, No problem.

10. February 2015 at 08:50

I agree with you, Ken. I think this is another case where viewing monetary policy through an NGDP targeting lens is helpful. I think it is useful to think of bonds as pulling cash from the private economy to pay for public expenditures, just as taxes would. I think the primary response to that is that the bondholder treats the bond as an asset, which has effects on spending and investing. But, if monetary policy is targeting NGDP, then monetary offset should make the difference between an economy that was taxed versus one that holds bonds insignificant.

Now, from a finance perspective, I do think there are some benefits to high debt levels for the US government, since the US government has developed a fairly unique product – risk free debt – which earns it economic profits in the global financial market. Foreign savers with a strong demand for very safe assets bid down treasury rates. This probably benefits emerging markets, also, since emerging market elites have an outlet for low risk saving, and so might be less inclined to create limited access rents in their own economies.

10. February 2015 at 08:53

OT: Cabin Fever by James M. Jackson (2014) – This is a good book, by an author who specializes in ‘financial thrillers’ The author writes well.

At those who ‘explain’ inter-generational transfers to Duda: (to paraphrase a LOL famous scene from Breaking Bad, involving Tuco Salamanca in the junkyard) you think Duda is stupid? He’s not stupid. If he can’t understand this concept after applying the full coin of his creative mind to it, it means it’s not a trivial concept to understand. There are so many assumptions in economics that indeed it’s hard to fathom. That’s why I’m doubly suspicious of Sumner’s NGDPLT–it almost like splitting the atom, with a potentially catastrophic runaway reaction. And this blurb from Worthwhile Canadian Initiative linked upstream is worth pondering: “Now read what Paul Krugman said: ‘First, however, let me suggest that the phrasing in terms of “future generations” can easily become a trap. It’s quite possible that debt can raise the consumption of one generation and reduce the consumption of the next generation during the period when members of both generations are still alive.'”

10. February 2015 at 08:55

George Mason University economists Vipin Veeti and Richard Wagner have a new paper criticizing NGDP Targeting. They claim it is “Chasing a Mirage.”

http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/398073/nominal-gdp-targeting-really-way-fix-fed-veronique-de-rugy

10. February 2015 at 09:31

Kenneth, I have always viewed it this way what matters is future real resources (labor and things like hard materials). If people are willing to work to produce what future generations need, and have the other needed resources – then the debt is somewhat irrelevant (but it can be no absolutes here). If we used up all the oil tomorrow, then that might place a burden on future generations – unless those folks marshal an adequate substitute. Money and debt just account for and facilitate the marshaling of those resources at a point in time – labor and the other ingredients. This all assumes a sovereign currency, and only debts denominated in that currency.

Abba Lerner has some interesting thoughts around this stuff. Good reading IMO, and Abba liked things like free markets despite being on the left. He describes that the declaration that national debt puts an unfair burden on our children is false. If our children repay some of the national debt these payments will be made to our children or grandchildren. They would no more be impoverished by repayment than they would by receiving the payments.

10. February 2015 at 09:44

Scott:

“I’d discourage you from thinking this way, unless there are externalities that are not priced in. Thus consumption of coal might be less useful, as it has negative externalities. But I don’t think you can say services are less useful than non-durable or durable goods.”

Thanks that’s helpful. The externalities was a part of it, but what made me think of this was when the 3Q14 GDP numbers came out with almost all of the increase in C coming via increased health care expenditures. I thought “well that might not make consumers feel better off the way a new car does, but if the increase makes us healthier then maybe that helps AS via more working hours and longer spans in the eligible workforce” Then I questioned myself. Just an FYI I was never considering any adjustments on the GDP calculations just considering what different impacts various types of spending had on AD and AS.

10. February 2015 at 09:46

I bet you could go for more global warming to melt that snow. I remember a professor at URI saying that we could end up with the climate of Virginia due to AGW and thinking not bad.

10. February 2015 at 09:50

Nice graph! Is “Snow in Boston” a time series on Fred now?

I hear that forex volatility Granger causes Snow in Boston.

10. February 2015 at 09:59

Government debt doesn’t have to be paid back. A government bond is an asset in itself; it’s not something that needs to be paid back

It doesn’t have to be redeemed, but it does have to be serviced via taxes.

One thing I haven’t seen mentioned yet here regarding the ‘make future generations poorer’ issue is the deadweight cost of taxes — and how it rises not with the tax rate but by the square of the increase in the tax rate, so that doubling a tax rate quadruples its deadweight cost.

Thus when shifting resources from A to B today while financing the transfer with bonds that will be serviced indefinitely into the future one drops a deadweight cost onto the future. Continue the process to accumulate larger future servicing costs and the real cost imposed on the future rises at the exponential rate.

As to the rest, I agree with the others that Nick Rowe has covered it well.

10. February 2015 at 10:06

Really great Nick Rowe links- all of ’em.

The Bob Murphy excursion was awesome.

10. February 2015 at 10:15

Might find this article from GMO interesting wrt SVM, corporate buybacks and low growth:

https://www.gmo.com/America/CMSAttachmentDownload.aspx?target=JUBRxi51IIBoe1yul9uERnfCmQoglFl9k5qwJSfHx8w%2fWCnFLmEb2MC9GoFnZVlslR5NzCRY1ajgn503icBv67VQg%2fNVUMWsYvi3A2%2fL%2bS28A7Pthjp7LmOfLYQfHMJc

10. February 2015 at 10:19

“Doug, I’m afraid you are wrong, they are equal by definition. Check out Andy Harless’s post. With trade, you have global saving equal to global investment.”

Sure you can, you just run a trade deficit with Jupiter.

10. February 2015 at 10:26

Woooo Elizabeth Warren!!!

“I strongly support and continue to press for greater congressional oversight of the Fed’s regulatory and supervisory responsibilities, and I believe the Fed’s balance sheet should be regularly audited – which the law already requires,” Ms. Warren said in an emailed statement. “But I oppose the current version of this bill because it promotes congressional meddling in the Fed’s monetary policy decisions, which risks politicizing those decisions and may have dangerous implications for financial stability and the health of the global economy.”

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2015/02/10/sen-warren-opposes-audit-the-fed-bill

10. February 2015 at 10:27

Actually, if you add up every countries balance of trade data you will see that the globe is in fact a net-exporter.

So, we must be running a trade surplus with Jupiter and savings is greater than investment….

But, If you are going to talk about global savings and global investment, then we are talking about a global economy… And everything here goes out the window as there is not a global monetary policy nor a global fiscal policy.

10. February 2015 at 11:05

Njnnja, And where do you suggest I blow the snow?

I am again forced to wonder where you’re shoveling it now. 🙂

10. February 2015 at 11:09

http://www.wikihow.com/Snow-Blow-Your-Driveway

In case this is helpful. Like market monetarism, some of it is non-obvious, perhaps even counter-intuitive to the uninitiated.

Plus, it has an awesome picture of a guy reading a hardcover book called INATRUCTIONS.

10. February 2015 at 11:15

TallDave, now Scott piles it in front of his window, obstructing his own view. If he uses a snow blower, the snow will fly everywhere, and end up in his neighbors’ yards, which he considers unfair. Krugman says that as long as the snow stays in his town, and everyone has a snow blower, then the neighbors will be fine on the whole, although other snow blowers might be better off at the expense of other shovellers. Bob Murphy put together a spreadsheet and a really long blog post pointing out that someone, somewhere will have to deal with Scott’s snow, and accepting certain assumptions, his neighborhood would be better off, the next block would have 10 extra inches of snow, the block beyond that would have less snow, the block beyond that would have more snow again, and the block beyond that would be unaffected.

10. February 2015 at 11:47

‘It doesn’t have to be redeemed, but it does have to be serviced via taxes.’

There are some acceptable levels of tax payments for interest. As a parent, I’m happy to vote for municipal bond offerings for schools that bump my taxes a bit.

Obviously you don’t want interest payments crowding out discretionary or other spending. I would have to hunt for a chart that shows what percentage of govt. spending goes to interest payments.

In a pinch, I guess you could do what Japan has done and just lower interest rates to near zero.

Some would ask why we need to pay interest on bonds the central bank could buy at zero interest.

This might compel savers to put their money into true investment vehicles or consumption rather than passive saving.

I don’t know — these are interesting times and the realities of what is happening are often making the theories look outdated.

10. February 2015 at 12:05

It’s an incontrovertible fact. CBs do not loan out existing deposits (saved or otherwise). S therefore never equals I except in Keynesian National Income Accounting procedures.

All CB held time/savings deposits are the indirect consequence of prior bank credit creation. The source of TD to the system, is DD, directly or indirectly via the currency route, or thru the CB’s undivided profits accounts.

Then voluntary savings which flow through the non-banks never leave the CB system in the first place. There’s just a transfer of ownership. The NBs are the CB’s customers.

10. February 2015 at 12:06

@CA – thanks for the link! What a devastating rebuttal of NGDPLT! Wow, Duda will withdraw his funding when and if he reads this report! Emperor Sumner is naked, not a pretty picture for a 60 year old man. Sumner is finished! And ironically done in by GMU, the same place where he will finish out his dotage. Finished! Sumner is finished! Wow, I wonder how Scott “Houdini” Sumner will find a way out of this bind…probably by selective quoting and wholesale ignoring. Stick a fork in it, Sumner is done! RL

Killer blurbs (sounds like MF could have written them):

from “NGDP Stabilization within an Ecology of Plans: Chasing a Mirage” by Vipin P. Veetil and Richard E. Wagner (2015)

“To posit a universal increase in the demand for money verges perilously close to reducing an economy to a representative agent. Within this analytical framework, there is no point even of making references to economic coordination because there is no one with whom a representative agent seeks coordination. Once a multitude of agents inhabit the economy, a uniform increase in the demand for money is surely a height of implausibility. …Only by reducing a macro economy to a representative agent can a reasonable theory ignore complementarity between micro and macro levels of an economic theory. The representative agent formalization can render market monetarism sensible, but only by eliminating any notion of an economy as consisting of interacting agents”

10. February 2015 at 12:11

Charlie J, Interest is around 1.3% of GDP, about the same as it was in 1974. The treasury could just stop issuing debt, or the Fed could just buy any bonds remitting the interest back to the treasury. If federal government debt issuance was stopped, the FED can use IOR to manage short rates.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=10m0

10. February 2015 at 12:38

flow5, I don’t see a distinction. The banks are the savers and the borrowers are the investors in your version. S still equals I. If there is an effect on total output, then RGDP has risen. If not, then only NGDP has risen. I don’t see how your distinction changes the basic story.

10. February 2015 at 12:46

@Kevin Erdmann

Tough to improve on that 🙂

But seriously, the key to residential snow removal is in fact figuring out where to put the snow. A good snowblower can toss that stuff up over 10 feet in the air. But you have to plan it out so that you give yourself plenty of space to build up the mountain. I’ve built plenty of snowbanks that are as tall as my roof; since they are triangle shaped you have to start the base far from the driveway.

There are trade offs – when you get a lot of snow you have to accept that your driveway is only going to be wide enough to get one car through, and the path to your mailbox is going to be tight. If you have a side or rear entrance forget about it.

Use the snowblower every 4-6 inches (even in the middle of a storm) instead of waiting for a foot or more to fall before trying to clean out. Utilize yard space, blowing snow from one part of the driveway to another until you can reach a yard (even your neighbor’s – people have to come together at times like these!)

As long as you aren’t sending sparks on your neighbor’s lawn you will be fine. And even if you do I’m sure you and he could come to some sort of arrangement that would allow you to continue to do so.

10. February 2015 at 13:15

Kevin — Once again Krugman offers some interesting ideas, but they’re undercut by the unwarranted assumption that salt is powerless at the zero temperature bound. I’ll try skim Bob’s post later, but I think most such detailed analyses suffer from the inevitable flaw that “snowfall” is too difficult to define given that every snowflake is unique and each “pile” of snow has unique characteristics (density, purity, etc) that make assigning an area an “average” snowfall a matter of great imprecision.

10. February 2015 at 13:22

Ray, just to be clear, I don’t agree with the authors of the paper. Additionally, I think you’d be wise to tone down your foaming-at-the-mouth reaction.

10. February 2015 at 14:46

CA, don’t listen to Ray. He and Major Freedom are trolls.

I glanced through the anti-NGDP-targeting paper you linked to, and couldn’t figure out what it was trying to say. It seemed to be saying, “NGPT targeting would not solve every problem on earth.” That’s fine with me. I like NGDP targeting because it is (much) better than inflation targeting via interest-rate targeting, not because it’s perfect.

Folks, on the government-debt-is-bad topic, I appreciate the thoughts but nothing moved any needles for me. Scott writes:

> Nick has a new post using a food analogy that

> explains the concept quite well.

Nick’s food analogy is great, and it explains how the government can get the invisible hand to do clever things. I get all of that. The proposition I disagree with is that the existence of government debt makes future generations poorer than they would be if the debt didn’t exist. I still think that’s nonsense. Yes, government policy can transfer wealth from kids to parents. That can chain. That can be financed with debt. In that case, our children are poorer, and there is debt, but those facts aren’t related. The same intergenerational transfer could happen without any debt, by simply taxing the kids and paying the parents. And there are plenty of ways for the government to take on debt that results in exactly zero change in the aggregate consumption of future generations. Like, say the government borrows money, and instead of giving it to old people, it hires people (of whatever age) who would be otherwise unemployed to dig holes and fill them in again. Later, it raises taxes to pay off the bondholders or their heirs. Sure, there’s been a transfer from children-who-are-not-bondholders to children-who-are, but how are our children collectively any worse off than if the government had let the unemployed sit around idle?

It still seems to me that anyone who thinks government debt makes our children poorer is forgetting that our children are bond holders too, which has been Krugman’s point, e.g., http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/02/opinion/krugman-nobody-understands-debt.html. Either that, or they’re assuming that every dollar the government spends is wasted regardless of where it came from, and if the government just let the private sector make all spending decisions, our children would all be better off, i.e., their actual issue is spending, not debt.

Really can’t imagine what I’m missing.

-Ken

10. February 2015 at 15:40

Kenneth, government debt is inherited, but government bonds are not necessarily inherited. It’s your choice whether to spend the borrowed money or leave it to your kids. If everyone decided to leave a bequest equal to the borrowed money, then it would not be an inter-generational transfer.

10. February 2015 at 16:44

Kenneth:

“CA, don’t listen to Ray. He and Major Freedom are trolls.”

No, I am not a troll. My intentions here do not fit the descriptions of a troll.

I do not post comments to get emotional rises out of anyone.

I do not post comments to intentionally upset anyone.

I do not post comments that harass anyone.

If you cared about truth and accuracy, which you clearly do not, then you would not call me a troll. You would consider me as someone who has as much a disagreement in what you believe, as you do in what I believe.

I usually skip over your posts because they too often contain fallacies, but because you called me a troll, I thought I should again show that you write fallacious posts because of the flawed theory you have decided to wed yourself towards. This will of course likely reinforce your desire to continue calling me a troll, but ultimately that is the real reason you do it.

Thus, you wrote:

“The proposition I disagree with is that the existence of government debt makes future generations poorer than they would be if the debt didn’t exist. I still think that’s nonsense. Yes, government policy can transfer wealth from kids to parents. That can chain. That can be financed with debt. In that case, our children are poorer, and there is debt, but those facts aren’t related. The same intergenerational transfer could happen without any debt, by simply taxing the kids and paying the parents. And there are plenty of ways for the government to take on debt that results in exactly zero change in the aggregate consumption of future generations. Like, say the government borrows money, and instead of giving it to old people, it hires people (of whatever age) who would be otherwise unemployed to dig holes and fill them in again. Later, it raises taxes to pay off the bondholders or their heirs. Sure, there’s been a transfer from children-who-are-not-bondholders to children-who-are, but how are our children collectively any worse off than if the government had let the unemployed sit around idle?”

It is not “nonsense” to point out that government debt makes future generations poorer than they otherwise would have been. Your argument that because the “transfer of wealth” aspect of government debt has a similarity to the “transfer of wealth aspect of taxation, in terms of outcomes, that this means government debt does not make future generations poorer after all, is fallacious. It is fallacious one two grounds.

One, you are presuming the fallacy that an outcome, I.e. a”reduction in overall wealth”, must have a unique cause X before it can be true that X causes that outcome. Replicating that same outcome with another cause Y does not prove that X is no longer a cause. The argument that government debt reduces overall wealth of future generations can be true even if there are a million other ways to do it.

Two, and I will point out that this quite expected, you are overlooking the opportunity costs in real terms, specifically, all the savings that the government has soaked up by issuing debt has made it impossible for thise same savings to have been invested in the production of goods in the market. And since today’s productivity depends on the quantity of previously invested capital, which is its own motive force totally apart from money and spending that physically enables a continually increasing capital stock (think an investment in a factory that produces capital goods, which themselves go into the production of more capital goods), what happens is that government soaking up of those trillions upon trillions of dollars in savings throughout history has caused a significant reduction in the capital stock that has accumulated until today. Government debt does not merely “transfer” money. It entails opportunity costs of reduced investment. Importantly, this is the case whether there are idle resources or not, and unemployment or not. It is not true for wealth creation that satisfies individual utility (the only real world utility), that “more labor” is better than “less labor”. Labor is a means, not an end, of individuals.

You have no right and are in no position to claim knowledge about what is better for others when you make these sweeping claims about government debt and what is “good for people”. The individual knows theselves and what they want more than government agents, and definitely more than you.

If there are people who are unemployed, only a market constraint can reveal utility deriving activity for individuals.

10. February 2015 at 17:15

Matt McOsker:

“Abba Lerner has some interesting thoughts around this stuff. Good reading IMO, and Abba liked things like free markets despite being on the left.”

Where did you get the idea that Lerner “liked markets”?

Have you read his book “The Economics of Control”?

Chapter l. INTRODUCTION. THE CONTROLLED ECONOMY

The fundamental aim of socialism is not the abolition of private property but the extension of democracy. This is obscured by dogmas of the right and of the left. The benefits of both the capitalist economy and the collectivist economy can be reaped in the controlled economy.

——-

He writes in the preface to “The Economics of Control” that he was long resistant to any “free market” analysis but finally he thanked Joan Robinson for getting him to overcome his prejudices against “Mr. Keynes great advancement in economic understanding”. Neat. A quasi-Stalinist tempered with some Keynesianism. That’ll work…

In 1980, two years before he died, Lerner was dabbling in the following price control system based upon this article by David Colander, a co-author of a 1980 book with Lerner:

Lerner found the implications of sellers’ inflation so important that, beginning in the 1960s, he changed his research program to center on finding cures for sellers’ inflation. Initially he toyed with various administrative wage and price control policies, but he found those lacking and soon gave them up. He replaced them, first, with a tax based incomes policy and ultimately, a market based[??!!!] incomes policy in which property rights in prices are set and individuals have to buy the right to change prices from others who change their price in the opposite direction. It was this idea that formed the basis of our market [???!!!!] anti inflation (MAP) book. (Lerner and Colander 1980) Under MAP, rights in value added prices would be tradable so that any firm wanting to change its nominal price would have to make a trade with another firm that wanted to change its nominal price in the opposite direction. Thus, by law, the average price level would be constant but relative prices would be free to change.

Lerner here proposed a barbaric system where one would be precluded from raising (setting) one’s one prices without trading the right to do so with somebody else under penalty of statist law.

Liked markets? Maybe like a control freak “likes” what he is controlling, as a zoo keeper likes monkeys.

10. February 2015 at 17:17

Holy crap, even MF is distancing himself from you!

Your move, Ruy Lopez.

10. February 2015 at 17:51

Axelrod’s new book:

“Summers would thereafter become the most dominant voice in the room, impressing everyone — Obama included — with his wizardry in discussing matters of politics and the economy. His proclamation that, absent aggressive action, there was “a one-in-three chance of a second Great Depression” was delivered with enough gravitas to spook the rest of the cabinet.”

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/10/david-axelrod-obama_n_6649688.html

10. February 2015 at 17:55

CA:

The Veetil and Wagner paper which critiques NGDP targeting makes some very important arguments not only in their own right, which is sufficient, but also in reinforcing what I have been saying on this blog for quite some time, with almost universal hostility and contempt (since the only way to counter advocacies of peace at the individual level is to move away from the ideas and reasoning, and towards ad hominem and guilt tripping, but I disgress).

Some high level, albeit very important passages, IMO, are:

“Conventional macro theory has a horizontal structure, in that it posits direct relationships among variables that exist on the macro plane. Within an ecologically framework, however, those variables don’t originate on the macro plane but rather are derivations from interactions on the micro plane. An ecologically-oriented macro theory must have a vertical structure in which macro variables emerge through micro-level interaction which is projected upward to the macro plane. Once this is done, NGDP stabilization, or macro rules of any type for that matter, cannot comprise a direct program for economic stabilization even though NGDP in a well-working economy would exhibit proximate stability (Salter 2013).”

And

“Within this conceptual framework, no effort is made to connect the macro and the macro levels. As noted above, the need to make any such connection is denied within the market monetarist framework. Within the context of Yeager (1956), the need for some such connection is put out of sight by invoking the presumption that the increased demand for money is general or universal. It is as if everyone suddenly decided to hold twice the volume of money balances that they previously held. A central bank that stabilized NGDP could in this case be construed as accommodating this general desire to increase money balances. In this setting, it is plausible to argue that less economic disruption would be involved in increasing the money supply than in allowing readjustment through the emergence of a new pattern of market prices. The plausibility of this line of argument, however, is not a definitive line of argument, and for several reasons that we will explore below.”

And

“To posit a universal increase in the demand for money verges perilously close to reducing an economy to a representative agent. Within this analytical framework, there is no point even of making references to economic coordination because there is no one with whom a representative agent seeks coordination. Once a multitude of agents inhabit the economy, a uniform increase in the demand for money is surely a height of implausibility. There can be a decrease in an aggregate measure of velocity without that decrease being distributed equally across agents. Furthermore, a decrease in an aggregate measure can be accompanied by increases in velocity among a significant number of agents. To point to such non-uniformity of changes in the demand for money, moreover, raises questions regarding the source of that change, which leads in turn into questions of whether recessions might have socially useful purposes that stabilizing NGDP would impede.”

It is as if knowing economics leads people to the same conclusions, while political punditry, of which (anti)market monetarism is included, is just one more hostile anti-social ideology among a myriad of similarly hostile, anti-social “warrior” ideologies.

Reading that paper is almost verbatim consistent with my existing ideas, which gives me hope that what I know is not impossible for others to know.

10. February 2015 at 18:12

Brian Donahue:

With no offense to Ray, I actually do not much like cavorting and allying with those who you may consider to be in the same camp as me. I hold no special feelings towards other anarchists or libertarians in general, no desires to defend them against attacks, valid or not, and no thoughts of duty or obligation to make sure their points are being understood.

I loathe the tribalist mentality that infects and plagues what is supposed to be academic discourse. I am on my own intellectually, through and through, and I give credit to those I have learned from and will gladly share with anyone who is genuinely interested. Hardly ever happens though. Those most hostile to me are almost universally oblivious to the source material. They think anarchism is crazy, period, and everything they think of what I write, is clouded and warped by that bigotry.

But there are those in the world who know what I know. I am happy they exist, and am happy they write and teach others. But that is as far as my feelings towards them go. I do not have any fears or any self-esteem problems. I am not afraid of death, torture, disease, and most especially I am absolutely not afraid of poverty. I love life a hell of a lot, which is why I choose not to experience those things as much as I am able.

Ray makes some good points, and he makes some points I think are wrong. But so what? It would be incredibly dishonorable of me to do what Sumner does, which is encourage someone simply on the grounds that he is “an enemy of my enemy”. He encourages those who call me moron and idiot, no matter how ridiculous are their claims. Think about that and let that sink in. I cannot help but conclude a total waste of education, time and money, not to mention irresponsibility. Purposefully encouraging falsehoods is what makes me have zero respect for him. He’s a lost cause, but perhaps there is hope for the younger generation who have less of an incentive to be afraid of divesting themselves of their lifelong intellectual capital. Not totally Sumner’s fault though, because he is living in a world where changing one’s mind so radically is often attacked vociferously by the myriad of tribalist yahoos masquerading as intellectuals.

10. February 2015 at 18:32

@MF,

1. Scott runs a pretty open comments section. No one can say that they are muzzled here.

2. Surely you are inured to being called a moron and an idiot, To me, that sort of childishness is easy to slough off.

3. Given #1, I don’t think Scott is responsible for #2, even when it (predictably) comes from pro-MM types like Daniel.

4. You obviously can take it- you’re still here, using Scott’s coat tails as a sort of platform.

5. Ray’s a nut, but as recently as six months ago, he was a reasonably cogent commentor at Marginal Revolution. Maybe he’ll snap out of it.

10. February 2015 at 19:03

Benjamin Cole:

“Monetary policy drives AD, and AD drives investment-Scott Sumner.”

“Dang right. Business dudes invest when they are pretty sure they can sell what they are producing. I was a business dude.”

This is what’s called the fallacy of composition, and is a very, very common occurrence among “business dudes” who are primarily concerned with their own direct demands for their firm’s products.

The fallacy takes place when one takes the truth that producers at the individual level have an incentive to invest more when the nominal demand for their products rises, and then extrapolating to the level of the economy as a whole and concluding the same dependency relation exists.

An individual producer is dependent on their consumers for maintaining their profits. Consumers of that one firm could always go to another firm for better products. All well and good.

But when you go to the level of the economy as a whole, then the dependency reverses. At the aggregate level, consumers as such depend on producers as such. Consumers as such have no other option than to consume what producers as such produce. This is true at the planet level, solar system level, galaxy level, and universe level.

Because the dependency for the economy as a whole is that consumers are dependent on producers, you cannot claim that “more demand for products” is the engine, the “driver” of investment. It is the other way about! Demand for output is driven by investment in the production of output.

Now before you knee jerk and cloud your mind with all sorts of haphazard one liners and narrowly constrained concepts, you would do well to understand the following:

At the level of the economy as a whole, and this may blow your mind, hopefully, because it blew my mind once I fully understood it and its implications, all classes of nominal demands are offsetting. As an example, and please let this point really sink in, the nominal demand for consumer goods is actually in competition with the nominal demand for capital goods and labor. Economics, as Sumner wryly referred to a few days ago, is about individual choices. If you choose to spend $100 on consumer goods, you necessarily did not also spend that $100 on labor, or capital goods, or anything else. Aristotle’s teaching helps here. The law of identity. Spending $100 on bread is NOT a spending on either labor, or flour, or wheat. It is only spending $100 on bread. That is what YOU bought. YOU did not buy anything else. Because you bought $100 of bread, you could not, did not, spend that same $100 on anything else.

If the nominal demand for output rises, this is not ipso facto a “stimulus” to higher output by way of investment. A higher nominal demand for output means all those people who are spending that money on output, are NOT spending that same money on any inputs.

Now I know it is so incredibly easy to ignore this and go straight to imagining what happens after by the receivers of said spending. “But MF,” you say, “Those producers can then ‘turn around’ and spend more money on inputs!”. This is no challenge, because to consider a rise in nominal demand on output means it is a recurring, continuing, maintained higher level of spending on output, which means less spending on investment, not more. If you imagine a higher investment with this higher demand for output, then you are just assuming higher investment and then ignoring the fact that the higher spending on output comes at the expense of investment.

The most productive economy is one where the ratio of demand for output to demand for input is the lowest it can possibly be subject to the constraint of market participants maintaining their health and happiness.

It is perfectly possible for the nominal demand for output to rise and total real output to fall, without any government interference or violent coercion from anyone. This occurs when people’s time preference rises so that they spend more on their own consumption and less on labor and capital. The expenditures are offsetting. NGDP may even rise modestly during this.

Imagine everyone ceased saving and investing, and started to devote 100% of their money earnings to their own consumption. Imagine wage earners liquidating all their investments. Imagine employers declared dividends, the sum of which is the entirety of their revenues, for the purposes of their own consumption.

What would happen? NGDP would likely either remain unchanged, or significantly increase. The nominal demand for output would be highly elevated. But what else would happen? The entire labor force would be laid off, because wages are paid from savings, not consumption. The production and sale of materials needed to produce goods would decline to virtually zero, since the purchases of materials is also financed by saving, not consumption.

As you can imagine, production in the aggregate would almost entirely collapse. Poverty would skyrocket. Billions would likely die.

The offsetting nature of spending is in full display here. I purposefully set up the extreme to point out the actual order of dependency to you. I am not predicting this will happen, nor consider it likely either. It is only to make it clear who depends on who in the aggregate. It is not consumers driving the world, it is producers. Individual producers depend on consumers at the micro level, but in the world macro level, it is the producers who drive the world.

Note: If you work for a living, you are a producer. If you are a government agent, central banker, or welfare recipient, then you are a consumer who is dependent on producers. Producers do not need “exogenous” consumers. Producers do not need “exogenous” spenders of money. Producers who respect each other’s property rights can produce, earn, and consume totally self-contained, totally endogenously.

Coercive consumers, such as central bankers, are leeches, nothing more. The only reason so many economists have come to believe that they are needed, is from their own false view of man; the view that man is hampered by some cosmic fault of insufficient consumption given his productive prowess. That the only thing producers want is money, so hey, why not have an institution that only gives them money in exchange for their goods. Unfortunately too many producers don’t understand they are being ripped off, because they cannot distinguish their earnings into earned and unearned components in real terms. They must treat all dollars as fungible because they are forced by law into living with it. But there are high losses, in real terms, being incurred by those who produce for money. The leeches are those who spend without producing.

10. February 2015 at 19:10

Charlie Jamieson: do read the Andy Harless post I referred you do. Saving in particular has a technical meaning in economics.

“A society that invests in a culture of education and hard work (like South Korea) will create quite a bit of productivity. A many that exercises is making an investment in himself, no capital required.” All of which involves deferred consumption and so is a form of saving, in the economic sense.

“Second, we can invest using either my savings and/or we can borrow money. Borrowing is a better way.” Borrowing someone else’s savings.

10. February 2015 at 19:30

Brian,

Yes, Sumner has the choice to start censoring comments, but he chooses not to.

I should change what I said. I don’t have zero respect, I have some respect, because he doesn’t censor. In that sense, I am glad. But not “appreciative”, because he said he doesn’t censor me because he believes I sound like a moron which supposedly helps his case.

In this way, we are taking advantage of our own opportunities, subject to respect for property rights. If Sumner censors, or even asks me to stop posting, I will abide. As far as that goes, we’re local anarcho-capitalists. The main difference is that I preach what I practise. I don’t advocate for gun toting psychopaths to *impose* my preferred money on him by force, by way of those psychos maintaining or introducing a higher degree of control over the world’s money and then threatening him and his family with violence if they dare go about living their own lives using their own bodies and property the way they see fit, without initiating violation of my property rights.

But he does that to me and everyone else who wants out of his bats#!t insane scheme.

The fact there are more such insane people in the world doesn’t give the least bit of credence to it. History shows that millions of people, the “consensus”, can hold not only crazy beliefs, but evil beliefs as well. I do not mind judging the world I live in to be predominantly crazy and evil, because of being left with irrational philosophical convictions from this age’s deplorable “philosophers”, who use it as a weapon. Future generations of hopefully more enlightened people would have no trouble in making the same judgment. You and I do it for the people who lived during the ages of slavery. Well, I do it today for the “open range” slavery that is statism.

10. February 2015 at 20:19

It still seems to me that anyone who thinks government debt makes our children poorer is forgetting that our children are bond holders too, which has been Krugman’s point…

Some quick thoughts that come to mind…

[] I’ll note without comment that a decade ago Krugman was saying the opposite with vehemence.

[] The “we owe it to ourselves, so it can’t really cost us” argument is an old, old one in Internet debate, made constantly back in usenet days before blog comments existed. It was much more true of housing debt then than it is now of government debt, which is owned more by foreigners every year. They used to say back then “so what if dollars are lost to lenders on housing debt, that means the exact same amount is saved by borrowers, it’s a wash because we owe it all to ourselves!” How’d that work out?

[] Who’s the “we” in ‘we owe it to ourselves’? When the children are paying the debt service through taxes, who will be the people collecting it? The thought that ‘collectively’ all will be better off, as the rich kids who inherit bond portfolios collect from the poor kids who are straining to make a living, rather superficially dismisses some Piketty-like notions that others might want to consider.

[] Again as to debt service, the deadweight cost of taxes just makes society poorer, period. That’s why the finance textbooks use the adjective ‘deadweight’. And that makes all those kids of the future collectively poorer, no way around it.

And again, that cost rises into the future not with tax rates but by the *square* of the rise of tax rates. There are some pretty dramatic examples in history of that exponential rise making itself felt with sudden impact.

Either that, or they’re assuming that every dollar the government spends is wasted regardless of where it came from, and if the government just let the private sector make all spending decisions…

Not at all. But because of the deadweight cost of taxes, the govt when spending money must produce significantly *more* than $1 of benefit for every $1 spent for society to break even. Private market transactions need produce only $1 for each $1 spent to break even.

Feldstein estimates “An across the board increase in personal tax rates involves a deadweight loss of 76 cents per dollar of revenue and only collects about two-thirds of the revenue implied by a static calculation.”

http://www.nber.org/papers/w12201

Your estimate of deadweight cost may vary, but the fundamental principle doesn’t. This is one sure way that borrowing today to produce a benefit today while dropping the cost into the future works to make the future poorer.

Does debt-financed govt spending produce so much *more* than $1 of benefit today for each $1 spent to cover that cost per dollar of tax debt service forever into the future, long after the gains of today’s spending, whatever they are, have receded into history? You decide. If you think so, given the exponential rate at which deadweight cost increases, how much more debt service can we pile up into the future with our short-term benefits still exceeding the long-term costs into forever by enough to produce a net gain overall? You decide.

10. February 2015 at 20:49

@Duda – it’s not good to close your mind. It’s like ignoring a new coding paradigm: OO vs procedural coding. Or like an old-timer I spoke to once who did not like web services, but preferred more low-level sockets type communications.

@BrianD- lol, good rhetoric. It’s clear you don’t read me, nor compare what I say now to six months ago. You’re just engaging in tribalism of the Sumner variety. I agree Sumner runs an open blog, but that can change. B. DeLong used to censor his comments, kicking me off once, and Noah Smith also deletes comments, in particular from this provocative physicist who blogs on economics (and does not believe much in Calvo / sticky prices): http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2015/01/i-have-no-idea-what-you-are-talking.html