The Great Inflation was caused by the Fed increasing the currency stock

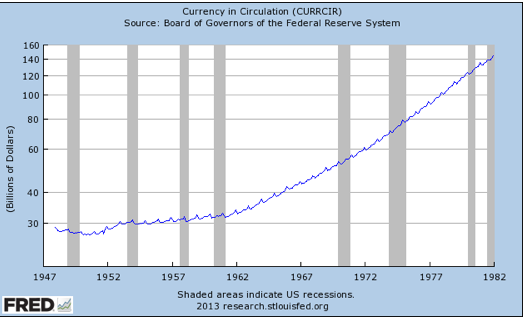

Some commenters argue that the Fed can’t control the monetary base. And they say that open market operations won’t affect the price level, as the Fed is simply swapping one asset for another asset of equal value. This is not true, as currency is not generally a close substitute for other assets. So when you increase the stock of currency via OMOs, the value of currency will usually fall. Between December 1947 and December 1964 the Fed increased the currency stock from $28.9 billion to $39.7 billion, and prices rose modestly. Then they started printed money like crazy, and prices soared between December 1964 and December 1981. By the end of 1981 the currency stock had hit $144.4 billion:

Some old style Keynesians will point to fiscal stimulus, but deficits weren’t particularly large during the Great Inflation (and indeed were very small in real terms.) Deficits actually got much bigger after the Great Inflation ended. The currency printing policy was instituted to bring down unemployment. It succeeded, but only up through 1969.

Some will ague that the currency stock is endogenous; the Fed controls the monetary base. Technically that’s true, but until 1914 the entire base was currency, and indeed when the IOR is zero it really doesn’t matter whether bank reserves are held as deposits at the Fed or vault cash. In any case, reserves are only a small share of the base. The Great Inflation was basically caused by printing lots of currency. That’s what central banks do. Fama was right.

Fiscal theories of the price level can’t explain the Great Inflation, nor can they explain the Volcker disinflation.

However the quantity theory of money also has trouble explaining the Volcker disinflation. The growth rate of the currency stock did slow after 1981, but only very slightly. Meanwhile the inflation rate fell sharply. Why doesn’t the QTM explain the Volcker disinflation? Because when inflation slows the demand for base money rises. Recall that inflation/interest rates are the opportunity cost of holding currency. So you actually need to model both the supply of currency (under Fed control) and the demand for currency (related to the opportunity cost of holding currency.) When you do both, you have a pretty good model of the price level.

Here’s another problem with the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. When the Fed decided to target inflation at around 2%, they pretty much succeeded. Raise your hand if you think Congress should be congratulated for bringing inflation down sharply in 1981-82 with the massive Reagan deficits, and then after 1990 holding inflation near 2% for decades. Congress adeptly nudges deficits up and down to keep that darn inflation rate pegged right around 2%. I don’t see any hands in the air.

Printing money is what the Fed does. (Speaking loosely—another agency actually runs the printing presses.) That policy affects all sorts of other variables, such as the fed funds rate. The Fed’s Great Inflation policy caused the fed funds rate to soar into double digits by 1981, so don’t assume that printing money causes lower interest rates, at least over any extended period of time.

Tags:

14. January 2013 at 11:43

Scott

When Brazil “Wipped Inflation” in mid 1994, inflation came from 50% a month in June 1994 to 3% in August and to 1% a few months later.

Concomittantly, money growth soared! That was only because money demand “exploded”.

No more long lines at the supermarket on pay-day to get rid of your currency quickly. And even the architecture changed. Apartments built in the 80s had huge storages (so you could buy several months provisions).

14. January 2013 at 11:50

Scott, wouldn’t other economists say that other forms of money are just as much MoA as currency, and are just as reponsible for the Great Inflation? I mean, isn’t the standard view that the Fed caused the Great Inflation by increasing the money supply? The alternative in this post then is not really argued for.

14. January 2013 at 11:57

Ahh, I see that You and Krugman coordinated posts today.

14. January 2013 at 12:17

“Some commenters argue that the Fed can’t control the monetary base.”

I assume you must be talking about me. Here’s what I said:

“Of course they *can* set the quantity. But if they set the quantity without looking at the short rate, the short rate will fluctuate violently between infinity and zero on an intraday basis, as I’ve discussed in many comments in the past few days.”

Whenever I said they “can’t”, I made very clear what I meant by that, which is not that they literally, operationally can’t. But if IOR is zero then away from the ZLB it is impossible, *in practice*, for the Fed to control the size of the base. The volatility of currency demand at any give rate is *huge* and dwarfs the size of reserves. Any excess resulting reserves will immediately drive the interbank rate to zero. Any reserve shortfall would cause interbank settlement failure and bank runs. There is simply no practical way to run policy *except* with the direct effect of determining the interbank rate. But then reserves quantity is not the policy instrument; the short rate is.

“And they say that open market operations won’t affect the price level, as the Fed is simply swapping one asset for another asset of equal value.”

No, “they” don’t say that. Where did I say that? Away from the ZLB, OMOs determine the short rate. The short rate, and the outlook for it, definitely affect the inflation rate. What I *said* was that because the Fed’s balance sheet is backed, there is not even a theoretical possibility of the quantity providing a price anchor. Also, at the ZLB, outright purchases of treasuries (or other assets) *may* effect the economy, including the price level, via portfolio balance effects. These have *nothing* to do with the quantity of the base though, since the same effect would be achieved by buying the same assets with t-bills instead of reserves. Also exchanging 30-year bonds for equities might have big effects. Nothing to do with money.

“so don’t assume that printing money causes lower interest rates, at least over any extended period of time.”

Agreed. If the CB is inflation targeting, any drop in the policy rate causing inflation will eventually have to be offset by a subsequent period of disinflationary policy high rates.

If you were referring to someone else’s comments, then this comment is irrelevant, and I apologize.

14. January 2013 at 13:18

“…when you increase the stock of currency via OMOs…”

Wait. How do OMOs increase the currency stock? OMOs swap bank reserves for Treasuries. Any effect on the stock of currency is secondary.

Under the old system (before IOR), I can think of various mechanisms by which open market purchases would eventually lead to an increase in the currency stock, but I wouldn’t expect the effect to be immediate. And OMOs would certainly affect the price level, but the mechanism has more to do with bank reserves than currency.

Now that we have IOR, I doubt OMOs would even have much effect on either the currency stock or the price level. You could say that “you increase the stock of currency by reducing IOR.” But OMOs just affect the liquidity of the banking system: unless the Fed is being stingy with reserves, which by all indications it does not intend to be, the demand for reserves will be almost perfectly elastic.

14. January 2013 at 13:30

Interesting…

Usually when people talk about the “great inflation” they mean 1974-1982.

Based on this chart, money creation began to take-off at the beginning of ’62. But, inflation was only 1% until ’65. Between 2-5% until ’73, and then jumped into double digits.

So, does CPI recat with an extreme lag? or is there a better measure for money supply growth?

14. January 2013 at 14:27

Scott, I have a question.

Why did Japan and Europe fall back into recession in the past year?

I understand the financial bubble and its bursting in 2008. But why–when capacity is slack, there are no bubbles to be seen, and inflation is low–did Europe and Japan fall back into recession?

14. January 2013 at 15:45

We can probably evaluate this better by comparing the currency in circulation time series to an inflation time series.

See here: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=eyF

14. January 2013 at 15:57

Your point is spot on, Prof. Sumner – Friedman went as far as to criticize the actions of his former mentor Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns for fueling the Great Inflation and ignoring his maxim that money matters.

14. January 2013 at 17:34

Good blog post.

14. January 2013 at 18:22

Never reason from a change in the quantity of money.

14. January 2013 at 19:07

“Never reason from a change in the quantity of money.”

Well that just threw NGDP targeting under the bus.

14. January 2013 at 19:15

Geoff: if you think that, you do not understand NGDP targeting. (Hint, consider the role of expectations.)

14. January 2013 at 19:38

Marcus, Good example. Real money demand also soared after the German hyperinflation ended.

Saturos. The Fed has dramatically increased the base recently, and yet the broader aggregates have barely budged. That’s because while the Fed actually controls the base, and they INFLUENCE M1 and M2. But they also influence the CPI and NGDP. So the aggregates don’t play an important role. They are not directly controlled by the Fed, and they are not the target of Fed policy. Control of the base is a necessary and sufficient condition for controlling inflation, at least during normal times. If you set the base at a level expected to produce on target CPI or NGDP, what possible gains can there be from also targeting M1 or M2? I would encourage everyone to read Fama’s paper on why currency is the key.

Niklas, Great Krugman post–I’ll do a link.

K, You said;

“Whenever I said they “can’t”, I made very clear what I meant by that, which is not that they literally, operationally can’t. But if IOR is zero then away from the ZLB it is impossible, *in practice*, for the Fed to control the size of the base. The volatility of currency demand at any give rate is *huge* and dwarfs the size of reserves. Any excess resulting reserves will immediately drive the interbank rate to zero. Any reserve shortfall would cause interbank settlement failure and bank runs. There is simply no practical way to run policy *except* with the direct effect of determining the interbank rate. But then reserves quantity is not the policy instrument; the short rate is.”

Put aside questions of terminology like “instrument”. The Fed controls the base, and by doing so influences interest rates, NGDP expectations, exchange rates and lots of other variables.

Your statement is simply wrong. The Fed doesn’t have to target interest rates. They can target exchange rates, NGDP futures prices, or nothing at all. The Fed didn’t even exist until 1914, I doubt interback rates rose to infinity in 1912.

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level people claim that OMOs don’t affect prices even when rates are positive.

Andy, When interest rates were positive an increase in the base affected the currency stock within a few days. The best way to think of this is to imagine that required reserves don’t matter. They are just a tax, and play no important role in the monetary system. (Fama made this argument.) Then reserves would be less than 1% of the base. Then go back to the pre-1914 system of making 100% of reserves into currency–reserves were vault cash. It would greatly simply things if we could simply talk about “currency” and not worry about whether it happens to be in the banking system or ourside. Otherwise we would need special categories for currency that happened to be held by drug dealers, or happened to be held by foreigners. When IOR was zero then bank reserves were for all intents and purpose simply currency. If I had used the monetary base instead of currency, my graph would look virtually identical, and I could say the Fed created the Great Inflation by printing too much base money. It’s essentially the same argument. I focus on currency because Bonnie and Clyde were wrong. Banks aren’t where the money is–wallets are. (Most of it.)

Doug, No, the Great Inflation refers to the 1965-81 period.

NGDP growth was quite rapid in the mid 1960s. As it slowed, more of the NGDP growth turned into inflation, and less into RGDP growth. Lags are not a big factor in NGDP, although because of sticky prices there is some lag in inflation.

Steven, Probably tight money.

Thanks Evan.

Garrett, That’s right.

Max, And that’s why I don’t. I reason form both a quantity of money change and a value of money change.

14. January 2013 at 20:26

Great post.

This has to be roughly right.

If not, then Obama s the Great Inflation Fighter, as inflation has been microscopic on his watch, compared to four percent to five percent at the end of Reagan’s watch.

Indeed, of you want correlations, it seems the larger and larger federal deficits lead to lower and lower rates of inflation in the USA…..

Same thing they discovered in Japan….

Obviously, monetary policy is what counts for inflation. And probably a lot for economic growth, although as Sumner points out, culture and government policy play a huge role too….

And what can be measured. The air is clean now in Los Angeles, whereas 50 years ago it was a grey opaque sheen that blanketed everything and cut visibility to a quarter-mile. On a good day. Your lungs hurt on a deep breath. Eyes watered.

How much is it worth to get rid of that?

14. January 2013 at 20:54

“Ahh, I see that You and Krugman coordinated posts today.”

I think Krugman is just jealous of the Tax Evaders, Drug Dealers, and Foreigners. All would be good marks for an additional Medicare Surtax.

14. January 2013 at 22:37

Austan Goolsbee reviews a new biography of Volcker: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/138485/austan-goolsbee/the-volcker-way?page=show

15. January 2013 at 01:54

Doug M,

NGDP was on an inflationary path from 1962 onwards, because it was considerably outstripping the LONG-RUN capacity for RGDP growth in the US. However, in the short-run, there was plenty of capacity for a rapid boom in the early-to-mid 1960s in the US. It was in the later 1960s, I think, that workers started to realise they were getting shafted and across the Bretton-Woods world countries tended to have more strikes and inflationary wage claims in the late 1960s, after expectations caught up. And so the spiral began.

In the UK at least, an important moment was the ascendancy of planning and Keynesianism in the early 1960s. Once we started listening to economists like Kaldor and trying to push for politically-convenient RGDP targets, we were set on the path to disaster.

I do worry a bit that, by targeting unemployment (i.e. trying to use demand management to control a real variable) the Fed might be setting itself down the same road in the long-run all over again.

15. January 2013 at 01:57

Here we go again. Scott says: “Put aside questions of terminology like “instrument”.”

I disagree, you should not do that, otherwise you confuse yourself on what it is the central bank does.

There is a difference between strategic and tactical targets in central bank operations. You really have to distinguish between an operational target (the Fed funds rate) and a longer-term target (inflation rate), and “monetary base” is a possible operational target, but in fact it is *not* the current target and not controlled. The operational target is the interest rate. But K already explained that much better than I ever could.

I again highly recommend the article “THE OPERATIONAL TARGET OF MONETARY POLICY AND THE RISE AND FALL OF RESERVE POSITION DOCTRINE” by Ulrich Bindseil from the ECB:

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp372.pdf

Money quote, applicable in spades to Scotts post above (“RPD” is “reserve position doctrine”, the idea that the central bank operationally targets a reserve quantity):

“It appears that with RPD, academic economists developed theories detached from reality, without resenting or even admitting this detachment. Economic variables of very different nature were mixed up and precision in the use of the different concepts (e.g. operational versus intermediate targets, short-term vs. long-term interest rates, reserve market quantities vs. monetary aggregates, reserve market shocks vs. shocks in the money demand, etc.) was often too low to allow obtaining applicable results. The dynamics of academic research and the underlying incentive mechanisms seem to have failed to ensure pressure on academics to ensure that models of central bank operations were sufficiently in line with the reality of these operations.”

Scott should really read that paper. I think this would clear up some confusions.

15. January 2013 at 04:59

Lorenzo from Oz:

“Geoff: if you think that, you do not understand NGDP targeting. (Hint, consider the role of expectations.)”

I guess I can see how my comment would have lead to that response, but Lorenzo, still, the way NGDP targeting would work would be by affecting the quantity of money. The quantity of money is what the Fed would change in order to bring about the NGDP target. The Fed would constantly have to “reason from a change in the quantity of money” if it wants to bring about a higher or lower NGDP growth.

The “role” of expectations is just that, a ROLE. It would not be a solo performance. The reason why it can’t be a solo performance is because if it were, then NGDP would not even need to be targeted. Investors and speculators can just expect what NGDP will be, and any fluctuating NGDP would be accounted for already once it occurs.

The (obvious) fact is that according to NGDP targeting theory, NGDP growth has to be constant. If therefore the money supply growth were to suddenly fall, then it means investors should expect a rising velocity, and if the money supply growth suddenly rose, then it means investors should expect falling velocity. One CAN reason from money supply in NGDP targeting.

15. January 2013 at 05:17

Scott:

If the central bank is issuing currency to meet demand, then we would expect newly created base money to sometimes become currency even before it is created!

Looking at the average shares of base money held by various groups, and then assuming that any increase will immediately (within a few days) be divied up in those shares, is bad economics. (Reserve ratio analysis is like that too.) What is the market process that causes an exogenous increase in base money to become 99% currency? I think it is more nominal GDP, and so more currency demand.

K:

Zero to infinity? Not very likely. Well, zero is possible, but the infinity is not. What happens is banks hold much larger reserves. Both the quantty of reserves and the demand to hold them are higher. The interest rates on things like interbank loans are similar to other rates. When currency demand rises, then banks reduce their large reserve holdings, and interest rates only rise moderately.

The reason this happens is that banks that hold large reserves earn the “infinite” interest rates when there is an increase in currency demand and banks that hold small reserves pay the “infinite” interest rates. To be able to earn and avoid paying, banks hold higher reserves when currency demand is low.

Why doesn’t that interest rates drop to zero when there are “excess” reserves? Because banks need to accumulate large reserves to avoid having to borrow and to be able to lend when there are less of them. The low interest rate period is when accumulating them is desirable.

No doubt such a system results in more volatility of short term interest rates than one in which a central bank creates and destroys money for the purpose of keeping interest rates stable.

Of course, I favor privatization of the issue of hand-to-hand currency, so any volatility in the demand for currency has no impact on the demand for base money. It just shifts the make up of bank liabilities.

If instead of currency demand, the problem is clearing balances, well, for every bank with favorable net clearings there must be a bank with adverse clearings. There is always a matching demand and supply. There is no reason for interest rates to zoom down to zero or shoot up to infinity.

Shining Raven:

We know that central banks like to target interest rates.

Some economists see this and suck up to the central bankers. They come up with reasons why targeting interest rates is wise. They explain to the central bankers how they can target interest rates more effectively. They explain how they need to adjust these interest rates to avoid disaster inflationary or depressionary disaster.

Other economists insist that regardless of what central bankers want to do, they really create and destroy money. And the creation and destruction of money has significant macroeconomic effects. The effects on interest rates that central bankers find important would be included, but these are not the most important effects. Spending on output, both real spending and inflation are the sorts of things these economists count as most important.

And finally, some economists are less interested in what central bankers do than with what monetary regime is best. What central bankers actually do is not directly relevant. The issues are what sort of monetary authority should exist and what should it do. Generally, those economists are especially interested in spending on output, real expenditures and inflation. I suppose that there are some economists of this sort who think keeping nominal interest rates stable is important. I suppose there are some economists who favor keeping interest rates stable, but with interest rates being market prices, the usual notion is that they should change to keep quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded.

In my view, interest rates should change with the supply and demand for credit, and should be as volatile as needed to clear the market. On the other hand, interest rates should never change due to changes in the shortages or surpluses of money of any sort, and the quantity of money (or the yield on money) should always adjust to demand to hold it.

15. January 2013 at 05:36

Personally, I think European and Japan went back into recession because of oil. Based on oil prices at the time, I called for a recession last April, and I was right for Japan and Europe–but not for the US. So what saved the US? (I might suggest the widening of the Brent – WTI spread at that time gives us a clue.)

15. January 2013 at 05:47

…While the Great Moderation came about because total reserves were “frozen”, despite continued increase in currency:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/11/25/creditism-and-the-great-recession/

15. January 2013 at 06:10

Geoff: that looks like examining both demand and supply to me. Which I am fine with.

15. January 2013 at 07:03

@Bill Woolsey: I am not really sure what you are saying.

I think we agree that central banks are monopoly issuers of bank reserves, which are needed in settlement of interbank transactions.

A monopoly issuer can either fix pice (interest rate) or quantity. The demand for settlement balances is incredibly inelastic, so if quantity is set (“reserve position doctrine”), the price is very volatile, i.e. interest rates fluctuate wildly. This has been tried under Volcker and was generally considered a failure, since nobody really cares about the reserve position, but people need to know interest rates for their investment decisions. Thus a stable interest rate is generally considered to be preferable.

Now, of course you can come up with all kinds of alternative scenarios how central banks could run their monetary operations. Perfectly fine, of that floats your boat. Nevertheless, this is how central banks operationally run their monetary operations: They operationally target an interest rate, and let quantity float.

This does not tell you anything about what kind of strategic long-range target the central bank has, this could be growth rate of some monetary aggregate, the inflation rate, or NGDP, if you insist. Nevertheless, the lever you have to affect your target is – the short-term interest rate for reserves, and nothing else.

15. January 2013 at 07:13

@Bill Woolsey: One more point. You write about the quantity-fixated guys: “Spending on output, both real spending and inflation are the sorts of things these economists count as most important.”

I do not believe that this is any different for economists who understand that central banks target an interest rate. Again, this does not tell you anything about the strategic target of the central bank, which can be one of several things. Sure, real spending and inflation and GDP are what really counts. But this you can of course also target by setting short-time rates.

I really really do not see this “quantity” transmission channel from central bank operations to the amount of currency and reserves held by banks and the public that the “quantity” guys see. Except for the primary dealers, the central bank cannot force cash or reserves on anybody, except by offering it cheaply and waiting for takers. To me, it seems to be demand-pull that determines the amount of reserves and currency out there, never supply-push. So I don’t really understand how the quantity idea is supposed to work.

15. January 2013 at 07:28

Bill, You said;

“Looking at the average shares of base money held by various groups, and then assuming that any increase will immediately (within a few days) be divied up in those shares, is bad economics. (Reserve ratio analysis is like that too.) What is the market process that causes an exogenous increase in base money to become 99% currency? I think it is more nominal GDP, and so more currency demand.”

Interest rates equilibrate the money market before NGDP has had a chance to adjust. The demand for currency is a downward sloping function of the nominal interest rate.

15. January 2013 at 07:30

It may be interesting to see how, if at all, the demand for base money is impacted by any entitlement cuts if they occur in a low interest rate, low inflation environment. I know my own reaction as a 50 year old would be, “Wow, I’d better save more….. or take more risk…..”

15. January 2013 at 16:07

[…] but that doesn’t mean I can’t quote someone smarter than me making a solid observation. This post by Scott Sumner rubs MMT’s nose into its poor treatment of monetary policy: Here’s another problem with the […]

16. January 2013 at 16:46

Rob, I doubt whether saving has a significant effect on the demand for base mony. Most people don’t save currency.