Recent links

I’m still catching up on a host of great posts. Let’s start with Yichuan Wang, who explains why rumors of tapering had such a big impact on various emerging markets. It was not the direct effect (which would obviously be tiny), but rather that it threw off their monetary policy because they foolishly focused on the exchange rate:

Here’s a link to my 3rd Quartz article on how much of the emerging market sell-off was about monetary policy failures in the emerging markets themselves. In particular, by trying to maintain exchange rate policies, central banks in these countries overexpose themselves to foreign economic conditions. The highly positive response to the recent delay of taper serves as further evidence that many of these emerging economies need better ways of insulating themselves from foreign monetary shocks. Much of the work, draws on blog posts from Lars Christensen. His examples comparing monetary policy in Australia and South Africa versus policy in Brazil and Indonesia were particularly helpful.

David Beckworth looks a a bunch of natural experiments on the efficacy of monetary policy at the zero bound:

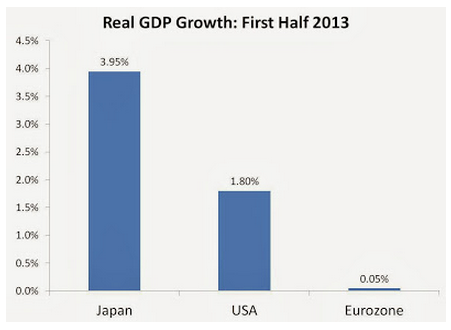

The first quasi-natural experiment has been happening over the course of this year. It is based on the observation that monetary policy is being tried to varying degrees among the three largest economies in the world. Specifically, monetary policy in Japan has been more aggressive than in the United States which, in turn, has had more aggressive monetary policy than the Eurozone.1 These economies also have short-term interest rates near zero percent. This makes for a great experiment on the efficacy of monetary policy at the ZLB.

So what have these monetary policy differences yielded? The chart below answers the question in terms of real GDP growth through the first half of 2013:

The outcome seems very clear: when really tried, monetary policy can be very effective at the ZLB. Now fiscal policy is at work too, but for this period the main policy change in Japan has been monetary policy. And according to the IMF Fiscal Monitor, the tightening of fiscal policy over 2013 has been sharper in the United States than in the Eurozone. Yichang Wang illustrates this latter point nicely in this figure. So that leaves the variation in real GDP growth being closely tied to the variation in monetary policy. Chalk one up for the efficacy of monetary policy at the ZLB.

However I’d caution readers that the BOJ has still not done enough to hit a 2% inflation target. They have had limited success, but need to do more. They should also switch to a 3% NGDP growth target, as inflation is the wrong target.

Ryan Avent has an excellent post that is hard to excerpt.

I would be shocked if the public had any real sense of what QE is. QE is confusing. And any expectations-based strategy that relied on the public understanding precisely what QE is, or what nominal output is, or for that matter what the federal funds rate is, would be entirely doomed. But I don’t think that’s how this stuff works. I also don’t think inflation targeting works by getting everyone to expect 2% inflation and raise prices or demand pay-rises accordingly. Consumers basically never expect 2% inflation, and consumers and producers alike seem to ask for as much as they think they can get based on their observations about what other people can get. That’s one reason why I don’t think the argument that “no one knows what NGDP is” is not a strong criticism of NGDP targeting, though I also think that it would be daft for a central bank to say it was targeting NGDP rather than just, say, national income.

I think most people operate using pretty simply heuristics. They have a feeling for what it feels like to be in a boom or a bust or something between. They have a sense for when inflation””in the economics sense of the term””is eroding their real incomes. They also have in mind something called inflation which basically means energy costs. My general feeling is that over the past 20 years (and in contrast to the two decades before that) most people have not much distinguished between real and nominal, because there has been no point to doing so. Complaints about “inflation” in this period virtually always boil down to complaints about unpleasant shifts in relative prices: more expensive gas and housing, mostly.

My sense is that what the Fed should do is target the trend path for a nominal variable that minimises the consumer experience “weak job market”. I think a nominal GDP level target accomplishes that. And once the Fed adopts that target the system will work as it does around any target. The Fed message will be intermediated by financial markets. Consumers will to some extent take their cues directly from financial markets and will to some extent take their cues from the reaction by sophisticated businesses to the reaction in financial markets.

And in an even more recent post, there is this gem (in reply to a Krugman post):

In his initial post Mr Krugman writes:

“One answer could be a higher inflation target, so that the real interest rate can go more negative. I’m for it! But you do have to wonder how effective that low real interest rate can be if we’re simultaneously limiting leverage.”

But if you create higher inflation you don’t need low real interest rates to solve the demand problem; it’s already solved! Maybe this is the confusion that keeps the economy in its rut. Markets are looking to the Fed, saying “which equilibrium, boss?”. And the Fed is saying that it would prefer the adequate-demand equilibrium but priority one is keeping a lid on inflation. And markets are saying “well I guess we have our answer”.

However his final paragraph is slightly off course:

Or to be succinct about things, there is no a priori reason to think that generating adequate demand requires rising indebtedness. But when an inflation-averse central bank is trying to generate adequate demand when the zero lower bound is a binding or near-binding constraint (as it was in 2002-3 and is now) it just might.

The first sentence in that paragraph is where he should have ended the post. If the central bank is inflation averse, even more debt won’t help. I’d add that the Fed could produce a robust recovery with 2% inflation. The problem today is that inflation is below 2%, and is likely to stay there.

As far as Paul Krugman’s comment, I have no idea what he is talking about. He seems to be steadily regressing from new Keynesianism to a crude version of 1930s Keynesianism. Keynes also thought that higher inflation targets were not a solution to the zero rate trap. But Krugman should know better.

PS. Justin Wolfers also has a very good column, discussing the fall in the PCE deflator in Q2.

HT: Stan Greer, and lots of other commenters.

Tags:

27. September 2013 at 08:20

The “natural experiment” is simply another historical episode of competitive devaluations — this is *very* old news, a re-run of a re-runof a re-run.

Anyone who learns anything from this hasn’t been paying attempt ion.

27. September 2013 at 08:55

Greg, Nope, foreign stocks rise on monetary policy easing, which shows you are wrong.

27. September 2013 at 09:11

Awesome Yglesias post where he reviews Tyler Cowen’s new book:

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/09/26/average_is_over_the_new_book_from_tyler_cowen.html

27. September 2013 at 10:14

The David Beckworth piece is based on only six data points in relatively noisy data. It will probably take an couple of years to generate sufficient data to really see the results.

I am going to stick with my prediction of Japan maintaining its post-2000 growth [1] average (3.3%), and the US and EU maintaining their post-2009 average (2.4% and 1.7%, respectively).

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2013/09/six-points.html

[1] By growth average, I mean average of RGDP growth numbers that are > 0 , i.e. non-recession times.

27. September 2013 at 12:16

“””I think a nominal GDP level target accomplishes that. And once the Fed adopts that target the system will work as it does around any target. The Fed message will be intermediated by financial markets. Consumers will to some extent take their cues directly from financial markets and will to some extent take their cues from the reaction by sophisticated businesses to the reaction in financial markets.”””

On of the big problems that MM faces is that people feel a need to explain a “transmission channel”, when it actually doesn’t matter. At all. It really doesn’t.

Consumers will take their cues from other consumers as they always do, they’ll take their cues from employment numbers, their friends, former lovers, and astrology. It’s messy on the ground, but what matters is the aggregate.

It’s impossible for a human to have an intuition of what it means to have people change their behaviour just so that it causes a 5% rather than 3.8% change in NGDP (or inflation to go from 1.6% to 2.1%). It is just humanely impossible to think through these things, except in fuzzy terms.

It’s a bit like the fact that we don’t believe that raising the price of an item (say a cup of coffee) by 1 cent will change buyer behaviour, but it must. There must be a price X and another X+$0.01 so that I will buy a coffee if it costs X but not if it costs X+$0.01. We can say “demand curves slope downwards”, but even I’m surprised that X exists.

Similarly, if the monetary authority is printing money until NGDP grows by 5%, then aggregate behaviour will change in a million tiny ways just so that it achieves that. How? Don’t know, hard to follow, really. Does it matter? No, not at all.

27. September 2013 at 14:26

Jason,

The eurozone is not the same thing as the EU.

Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the UK are EU members, but are not on the euro. This obviously is purely a semantic issue as it does not affect your analysis. However when someone says “EU” most people quite correctly think that person is in fact referring to the entire EU and not just the eurozone.

More importantly, in my opinion, it is logically incoherent to compare the average growth rates from the first half of the year with the average of *the subset of positive growth rates*. Yes, Japanese RGDP growth rates are more volatile than the growth rates of the larger currency areas (which are also less open to extra-currency area trade) to which they are being compared. But there was really no way of knowing a priori that the Japanese growth rates from the first half of the year were going to be positive, was there?

The quarterly real GDP growth rate has averaged 1.8%, 1.1% and 1.0% at an annual rate in the US, the eurozone and Japan respectively since 2000Q1. Thus Japan had an extremely good first half of the year, the US had a very average first half of the year, and the eurozone had a worse than average first half of the year when compared to their resspective averages since 2000Q1.

27. September 2013 at 16:43

Excellent blogging. Justin Wolpers had a great post…just don’t read the comments…the public would rather freeze in the dark with prices frozen than prosper with mild inflation…

27. September 2013 at 21:27

This needs a response: http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2013/09/the-age-of-oversupply.html

Again I recommend just sending him the serious on the actual behaviour of nominal hourly wages during the crisis. Also, this paper does look interesting: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/2013b%20coibion%20unemployment%20persistence.pdf

27. September 2013 at 22:08

…the public would rather freeze in the dark with prices frozen than prosper with mild inflation…

And that’s why Obama, other govts and central bankers let unemployment and recessionary conditions last for years longer than necessary — now and thru history (1930s). They are giving the voters what they want. Median Voter theorem. Simple.

No Krugman-like aspersions of evil by anybody, no conspiracy/class-warfare theories of the rich downing the rest, or any other such thing necessary. The politicians are giving the voters what they want. That is all.

And the voters are massively ignorant, they don’t know what’s good for them. Public Choice 101. So they decide that what was bad for them in the 1980s must still be: inflation. Perfectly rational on their part. Just ignorant.

Which brings to mind an article I just saw saying the prime requirement of a newly appointed central bank head today should be not technical expertise, central banks are full of people who have that, but to be a *great story teller*.

Because stories are what reach and teach the public — and the public has an awful lot to learn about the new monetary policy realities.

28. September 2013 at 00:56

Evan Soltas’ new post:

http://esoltas.blogspot.com.au/2013/09/a-new-strategy-for-fed.html

28. September 2013 at 01:13

Scott,

Go read the comments at Wolfers post.

Everyone, go read the comments please.

You know the difference between the commenters and all the unemployed MM wants to help?

Every one of the those commenters VOTE. And they are home owners.

What kind of bubble do you people live in? Have you not watched Cruz, Paul, Rubio take total control of the GOP’s base?

The thing is ALL OF THE COMMENTERS can be reliable supporters of MM!

Scott will admit the MM makes it easier tot shut down the government!

Why in the hell are there no MM articles telling Rush Limbaugh’s audience, that we have a great idea for making it easier to shut down the government and fire half the people who work for the Fed?

Those things are TRUE!

No one here will / can deny them.

NO ONE HERE CAN DENY THEM.

Why would we not say the true things to a powerful voting block, who have the same basic general small government outlook as we do?

Jesus, it’s the Krugman crowd we are basically trying to trick into bending over while we weaken their stature, status, and the tribe that they support.

It doesn’t matter if we are just as feeling about the plight f the unemployed as Krugman.

it doesn’t matter if we’re uncomfortable by the knee jerk, don’t really understand money rubes.

HOW YOU PEOPLE FEEL MEANS NOTHING!

Our thing makes it easier to shut down the government!

Our thing makes it easier to default on government debt!

Do you think the Krugman crowd doesn’t know this?

No they are reading these words just like you are.

Don’t lie about what MM is and does.

That’s all I’m asking.

if you don’t want to make it easier to shutdown the government and default on government debt, than maybe MM isn’t for you.

If you don’t want to make it easier to fire public employees, than maybe MM isn’t for you.

But if you so want MM and its upsides,that these things are not important, than STOP BEING GREEDY.

You don’t get to have your cake and eat it too. ALL economics has a ying and yang, it gives and it takes.

And we laugh ho-ho at the Keynesians who never want tax cut fiscal stimulus, the Keynesians who never want to not grow govt. during good times.

MM has a YANG, its not all just YING.

At run time, when the program starts, 51% of MM is about taking away the punchbowl, so the 49% where we take some inflation, never happens.

Scott is right that MM could legitimately have kept Barrack Obama from being elected.

How is that not a headline to the half people who want that to be true?

What is the goal here exactly?

28. September 2013 at 01:21

To repeat, defaulting is still a very bad thing. But yeah, I agree with Morgan. But does Scott really want to alienate liberals? Liberals who will have more of a hand in whether his policy will actually get implemented? Not that they should be alienated, of course; MM is good for everyone. (Except maybe central bankers.)

28. September 2013 at 01:31

This is Ryan Avent doing the Ying

“My sense is that what the Fed should do is target the trend path for a nominal variable that minimises the consumer experience “weak job market”. I think a nominal GDP level target accomplishes that. And once the Fed adopts that target the system will work as it does around any target. The Fed message will be intermediated by financial markets. Consumers will to some extent take their cues directly from financial markets and will to some extent take their cues from the reaction by sophisticated businesses to the reaction in financial markets.”

That is exactly right.

EXCEPT, there is the Yang.

That very consumer experience a “strong job market” will ONLY OCCUR for the private sector.

The public sector will face conservatives who don’t have to fear:

1. a crisis in capitalism that expands social safety net.

2. less concern over shutting down the government or defaulting on debt.

3. more positive economic upside from no giving public sector pay raises, smashing union rules, and making the public sector become more productive (headcount reductions).

The difference between me (and hopefully you peoplee) and Ryan Avent, is that he WANTS the Ying first, and oh btw, he is either too stupid to know about the Yang, or he isn’t stupid and he’ll hold his nose on the Yang to get the Ying.

I who am not stupid want the Yang, and so as a pragmatic Austrian / pragmatic libertarian I will hold my nose and put up with the Ying.

The thing is Tyler Cowen says Milton Friedman deserved three Nobel Prizes for economics.

And boys and girls Austan Goolsbee doesn’t call Friedman a pragmatic libertarian bc Milton was like Ryan Avent, no sir.

Uncle Milty HATED government, he was a yanger, and he was willing to do a lifetime of monetary theory to figure out how to use money to get his yang on.

28. September 2013 at 01:37

Saturos that isn’t HONEST.

And the pro-government people are reading this blog.

So let’s put the meat in the window, and find out once and for all if Ryan Avent is a stupid of not.

28. September 2013 at 05:44

Jason, You said;

“By growth average, I mean average of RGDP growth numbers that are > 0 , i.e. non-recession times.”

Lots of luck convincing anyone that a non-average “average” is interesting.

Luis, Good point.

Saturos, There’s not much to reply to. He starts off saying that the oversupply hypothesis is intriguing, and ends up saying it’s probably wrong. I’d say it’s certainly wrong. I’ve addressed wages many times in earlier posts.

Morgan, I’m trying to convince my fellow economists, not commenters.

28. September 2013 at 06:26

Scott,

You have already convinced your fellow economists.

Perhaps Al Capone helps here:

“You can get much farther with a kind word and a gun than you can with a kind word alone.”

Do you really think the Fed economists you want to convince aren’t gun shy bc of Justin’s commenters?

Really?

Answer me this, what if Justin wrote, “If conservatives really want to win the government shutdowns and debt ceiling hikes and public sector wage cuts, THEN we should get the Fed on an automatic pilot…”

The tone of the comments would change. And vitriol from the left would EMBOLDEN the everyman right. And Scott, those lefty commenters WILL NEVER NOT LISTEN TO KRUGMAN. And Krugman will never support NDPLT.

The line on Friedman is that he viewed Monetarism as an answer the Keynesians.

But FIRST he knew he had to convince the crowd most likely to follow the tight money Austrians.

Non-economists do not care about monetary policy.

And when their guy in office, they don’t care much about inflation either.

We ALL KNOW Scott Sumner is a nightmare incarnate for Fiscal Stimulus (spending) hawks. We ALL KNOW some of the “economists” you claim to want to convince don’t really care about economics, they just want a bigger state and economic arguments are just a way to get it.

We all know that you Scott are a true monetary policy believer. You want the economists to pay no attention to the tight money conservatives that vote, own stuff, and expose how unpopular Justin Wolfers is politically.

We know that after NGDPLT is in place and the left is screaming we need more Fiscal and they can’t get it, that you will be just as noble when you say this isn’t abut politics and its just good economics.

You are an equal opportunity offender.

But, NGDPLT is not neutral politically. Compared to status quo, NGDPLT is the response to Neo-Keynesian efforts to absorb the and respond to Monetarism.

Compared to status quo NGDPLT does some super awesome stuff that will appeal the same guys politically that made Friedman who he is.

Why on earth would we not admit what everyone in economics knows, but is not known by the guys who’d be on our team politically.

Why does MM as a policy choice trying to get into mainstream thought, choose to use oars, instead of dual 500 HP engines?

If there’s some great political strategy here that I’m not considering let me know

28. September 2013 at 06:42

Sumner: Historian, not an economist.

Beckworth: I wonder how long it will take to understand that monetary inflation biases real productivity measurements upward.

If economy A’s central bank prints X per year, and economy B’s central bank prints 2X per year, and both economies have identical real output, then the measurement of economy B’s real output would be greater than that of A.

But let’s suppose the measurements are accurate for Japan, US and the EU. It does not prove the thesis that more inflation generates more growth, not even in any contrived example that seeks to avoid “highly inflationary” scenarios that are “obvious” cases that more inflation does not generate more growth. For the question that remains is what kind of growth? Not all equal aggregate growths are equal in every way. An aggregate output can contain more weapons of war than medicine. Or more goods consumed by public employees and less goods consumed by producers.

Or, and more likely the case with Japan, more goods of higher order and not enough goods of lower order, despite “aggregate” output being higher. Once a central bank brings about an unsustainable boom, it is powerless to stop the correction. It can only ever delay it in the short run.

We haven’t had real sustainable growth since 2008. It’s been completely artificial and engineered by worldwide inflation, for the first time in history.

This is what all monetarists ignore. They ignore it because they are blind to monetary policy itself having detrimental effects in the positive sense, that is, detrimental effects coming from inflation rather than “not enough inflation.”

The only time detrimental effects of monetary policy in the positive sense are ever researched or studied by monetarists, is alongside “greater benefits” of it, or “more than outweighs the costs” type thinking, that, of course, cannot be observed because one half of the argument, the counter-factual of “worse alternative” is unobservable.

So we’re told that we should rejoice at Japan because of this chart, and we’re seemingly supposed to ignore the rigorous economic study of what is taking place.

28. September 2013 at 08:14

Morgan, You asked:

“Do you really think the Fed economists you want to convince aren’t gun shy bc of Justin’s commenters?”

Yup.

28. September 2013 at 09:42

Joe Gagnon:

“Chairman Bernanke would deny that political pressure influences his vote, and he even went out of his way to make a public appearance in Texas after Rick Perry made his threat. But FOMC members all read the papers. They see the virulent opposition to their policies on the right and the silence on the left. (Paul Krugman is a big exception, but he is not a politician.) They want to avoid any Congressional action that would reduce their independence in the future, in part because they think this might lead to even worse economic outcomes than we are currently experiencing. I think they should stick to achieving their current mandate and not fail to achieve it out of fear of what a future Congress might do. In my view, Congress and the president are solely responsible for making laws and the Fed is solely responsible for achieving its mandate. But I am pretty sure some FOMC members either consciously or unconsciously disagree with me and shade their actions out of this concern. ”

Mankiw

“If Chairman Bernanke ever suggested increasing inflation to, say, 4 percent, he would quickly return to being Professor Bernanke.”

Scott, you don’t care about the rubes who own most of America, but shouldn’t you at least in light of above, consider the econos at the Fed aren’t as pure and courageous as you?

Just in case they are a tad softer, a tad more guns shy…

Maybe they legitimately fear more Congressional oversight if they gdeviate.

Scott, you admit that when GOP holes Presidency, nobody seems to mention inflation…

YOUR PLAN could change the tone of Congress in the near to mid term!

Why not help your brothers out?

28. September 2013 at 09:50

Scott,

“Lots of luck convincing anyone that a non-average “average” is interesting.”

I did a more systematic analysis in response to Jason’s claims than the one I did yesterday to see how significant the first half of the year results were.

The year 2000 is a reasonable starting point for all three currency areas since the eurozone only officially came into existence in 1999.

I averaged the quarterly RGDP growth rates by first and second halfs of each year. That produces 27 observations for each currency area. The average of the semiannual averages of the quarterly real GDP growth rate at an annual rate is 1.8%, 1.1% and 1.0% for the US, the eurozone and Japan respectively since 2000. The standard deviation of the semiannual averages of the quarterly real GDP growth rate at an annual rate is 2.40, 2.24 and 3.11 for the US, the eurozone and Japan respectively. Thus the first half of the year RGDP growth performance for the US, the eurozone and Japan is (-0.06), (-0.44) and (+0.98) standard deviations away from the mean.

Another way of looking at this is to rank the semiannual averages of the quarterly real GDP growth rates. The US first half performance ranks 16th, the eurozone performance ranks 21st, and the Japanese performance ranks 4th out of 27 half-years.

28. September 2013 at 10:12

I found a spreadsheet error.

The average of the semiannual averages of the quarterly real GDP growth rate at an annual rate is 1.83%, 1.09% and 0.91% for the US, the eurozone and Japan respectively since 2000. The standard deviation of the semiannual averages of the quarterly real GDP growth rate at an annual rate is 2.16, 2.29 and 3.11 for the US, the eurozone and Japan respectively. Thus the first half of the year RGDP growth performance for the US, the eurozone and Japan is (-0.01), (-0.43) and (+0.98) standard deviations away from the mean.

28. September 2013 at 10:22

“Thus the first half of the year RGDP growth performance for the US, the eurozone and Japan is (-0.01), (-0.43) and (+0.98) standard deviations away from the mean.”

should read

“Thus the first half of the year RGDP growth performance for the US, the eurozone and Japan are (-0.01), (-0.45) and (+0.98) standard deviations away from their mean performances respectively.”

29. September 2013 at 05:39

Morgan, As soon as the Fed starts doing less than the consensus of economists believes they should do, I’ll take your hypothesis seriously.

Mark, Thanks for doing that analysis. That seems to support David’s post.

1. October 2013 at 14:36

“Lots of luck convincing anyone that a non-average “average” is interesting.”

Consider it a poor man’s principal component analysis:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principal_component_analysis

This looks like a line with a few deviations at the gray bars to me:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=mXH

The numbers I put down are what you get when you read off the slope of a line fit to to RGDP data. Non-recession times end up getting weighted more than recession times because there are more points. Simply averaging quarterly RGDP growth numbers is a terrible procedure that only makes sense if there *aren’t* relatively rare large deviations.