“Don’t bother me with facts, my model tells me everything I need to know”

That’s a made up quote, and perhaps a bit of hyperbole. But it illustrates something that really bugs me about the blogosphere. People make all sorts of claims about monetary policy near the zero bound:

1. QE has no effect

2. Negative interest rates would be contractionary

3. Central banks cannot depreciate their currencies at the zero bound

And then when the theories are actually tested and the results are in, they keep making the same claims, seemingly oblivious to the fact that their theories have been discredited.

Today I’d like to talk about negative interest rates on reserves (IOR). There are two broad approaches to this topic. There’s what I’d call the “finance approach”, which claims negative IOR would actually be contractionary, because . . . well I’m not quite sure why. Something about how it interacts with the banking system. I used to see these articles in the Financial Times.

I tell people to ignore banking when studying monetary policy—focus on the supply and demand for the medium of account (base money). Negative IOR causes a fall in the demand for base money, and thus is expansionary. Period. End of story.

But just to make sure, let’s look at reality. The Telegraph has a nice story on negative rates on Sweden, which was the first country to adopt the policy I proposed in early 2009. (I deserve zero credit for NGDP targeting (the idea’s been around forever), but surely at least a tiny bit of credit for negative IOR.) Before getting to the Telegraph story, let’s look at how markets responded to a recent negative IOR shock:

Updated March 18, 2015 11:14 a.m. ET

STOCKHOLM””Sweden’s central bank has slashed its key policy rate deeper into negative territory and expanded its bond-buying program to prevent the recent appreciation of the Swedish krona from stifling a budding revival in inflation.

The Riksbank, the Swedish monetary authority, lowered its benchmark rate to minus 0.25% from minus 0.1% and said it would buy government bonds worth 30 billion Swedish kronor ($3.45 billion), an extension of bond purchases worth 10 billion kronor announced earlier. The repurchase rate had stood at minus 0.1% since February, the first time it was cut into negative territory.

. . .

The Swedish krona fell sharply against the euro, which gained about 1% against the krona in the minutes after the announcement, hitting a high of over 9.34 kroner. Sweden equity markets jumped to a record high with the OMX Stockholm 30 Index up 1.5% at 1,700.

Yup, cutting the IOR is expansionary, even when in negative territory. And those sorts of market responses (assuming at least partly unexpected, as some of them are) should have been it for the “finance” theories that negative IOR is contractionary, but you can never drive a stake through these zombie theories. There are still those “models” . . .

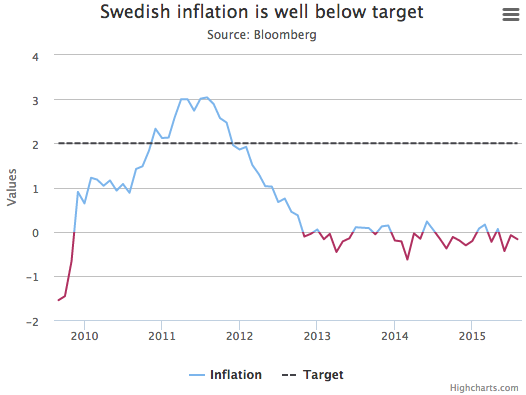

The Telegraph story looked at some macro data, which at first glance looks like a mixed bag. Inflation has been running around negative 0.1% to minus 0.2% for 4 years:

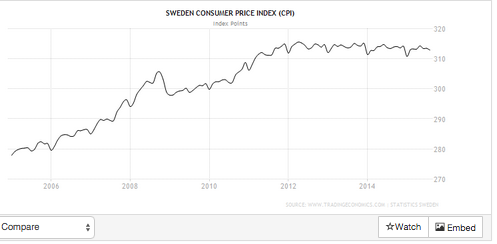

It looks like 3 years, but that’s a quirk of year over year data, the actual CPI shows it’s 4 years:

It looks like 3 years, but that’s a quirk of year over year data, the actual CPI shows it’s 4 years:

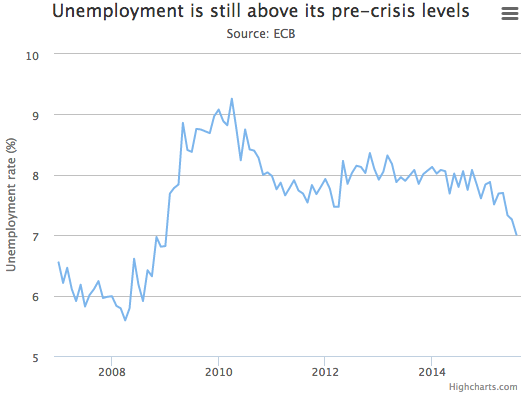

So that doesn’t look very good for negative IOR. But recall that in most countries inflation has recently been falling sharply, due to the plunge in oil prices. Inflation has never been a reliable indicator. NGDP growth has recently been accelerating in Sweden (up at a 9% annual rate in 2015, Q2), and the most recent RGDP growth shows 3.2% over the past year, which is higher than in previous years. The best evidence comes from the unemployment rate, which leveled off at 8% after the Riksbank’s disastrous monetary tightening of 2011, but has recently fallen to 7%.

So that doesn’t look very good for negative IOR. But recall that in most countries inflation has recently been falling sharply, due to the plunge in oil prices. Inflation has never been a reliable indicator. NGDP growth has recently been accelerating in Sweden (up at a 9% annual rate in 2015, Q2), and the most recent RGDP growth shows 3.2% over the past year, which is higher than in previous years. The best evidence comes from the unemployment rate, which leveled off at 8% after the Riksbank’s disastrous monetary tightening of 2011, but has recently fallen to 7%.

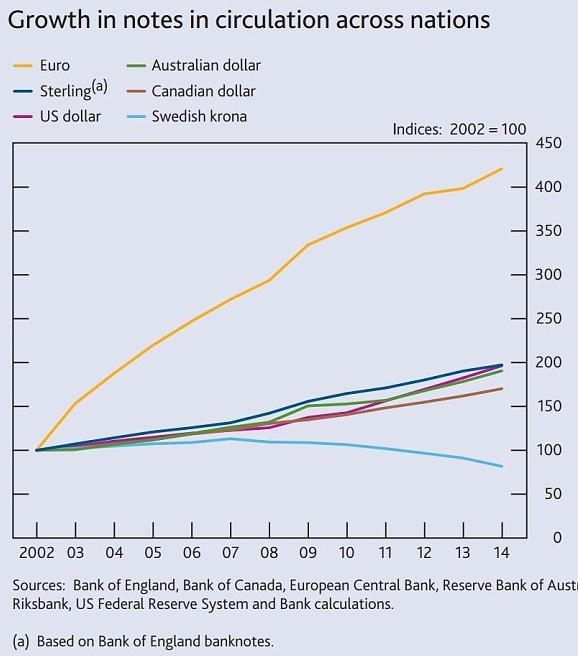

One final graph, which is really weird. While other countries are seeing a surge in currency hoarding, Sweden is experiencing exactly the opposite, despite the negative rates. What’s up in Sweden? Will the Nordic countries be the first to adopt the sort of cashless 1984-style panopticon state that is so beloved by authoritarians and Puritans everywhere?

PS. I have a reply to John Cochrane over at Econlog.

Tags:

29. September 2015 at 08:48

Interest rates are even more negative in Switzerland than in Sweden. When the Swiss central bank abolished the lower bound on the eur/chf exchange rate, they also lowered interest rates to negative 0.75%. Interestingly, commercial banks reacted by increasing the mortgage rates. Thus, they improved their margins in the mortgage business at the expense of home owners. Isn’t this somewhat contractionary?

29. September 2015 at 08:56

Isn’t this a really good-news story for Sweden, moreso than is even highlighted here?

If I’m properly reading the graph, the 2015Q2 results of a 9% yearly-rate NGDP growth combined with the evident near-zero inflation translates to a 9% yearly-rate RGDP growth.

Through quantitative easing and negative interest rates on reserves, the Riskbank has apparently engineered an incredible boom whilst maintaining not just tame inflation, but price stability. Their policies should be a world model, at that rate.

More seriously, inflation-hawk opponents of QE programs suggest that the increased amount of base money will eventually result in tremendous inflation. Is there any historical precedent for this, where a hyperinflation event begins not from an already-high inflation rate, but from a very low one?

If historical evidence suggests we can only get to (say) 10% inflation by first spending a while passing through 2%, then I really don’t see the problem.

29. September 2015 at 09:19

“Don’t bother me with facts, my model tells me everything I need to know.”

I agree! A major problem with the economics profession. The signal to noise ratio is too high to disprove most models. And, it is too easy to rationalize a deviation. Take the Phillips curve (please) this model was debunked in the ’50’s, it doesn’t fit 70’s stagflation, the Reagan recession and recovery, the 90’s dot com explosion, or the present state. It has been consistently useless. Yet, people still hold on to it!

It gives your profession the problem of being “not even wrong.” If no theory can ever be satisfactorily dismissed (or confirmed) it is all just noise.

As a finance guy, who believes that banking is an essential part of money creation, negative IOR should be expansionary! The finance theory I grew up with, is that banks create money when they lend. Banks lend when they have an incentive to do so. Their incentive is the spread between the risk-less asset (cash) and the risky asset (loans). IOR creates and artificial return on that riskless asset.

29. September 2015 at 09:25

Pot. Kettle. Black. Projection Noted. is the theme of this blog post, by model-envious Sumner, who doesn’t have a model other than his twisted words.

Then Sumner drops this koan: “Negative IOR causes a fall in the demand for base money, and thus is expansionary. Period. End of story.” – what??? Why? First off, negative interest on reserves means the central bank member banks give interest to the central bank, the opposite of the US. So the have incentive to lend excess reserves. But the incentive is only to the extent they have customers who wish to borrow at a rate greater than what the banks pay the central bank. And you cannot magically create demand for loans if that demand does not exist, even if you lend money for free, assuming the bank just doesn’t want to give money to some con artist and lose it all. Sumner thinks not? Not clear what Sumner thinks, since he always seems, like the Riddler in Batman, to pose more questions than answers.

29. September 2015 at 09:27

Sweden’s core CPI is rising at a steady rate of about 1% since the crisis. There’s a definite change to a lower rate in 2010, but no change in 2012 …

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=1YDq

29. September 2015 at 09:49

The public don’t have negative interest rates on their bank deposits so that probably helps explaining the lack of hoarding. The banks want to protect their retail customers from that effect, probably fearing that would upset them (us) so much that they would lose their profitable business (mortgages etc) too.

Also paying with cards (and phones) has become very popular in Sweden, especially among the younger generations. Many have virtually no cash at all.

The negative IOR that the Riksbank uses is actually 0,75% lower than the so called repo rate. See http://www.riksbank.se/en/Interest-and-exchange-rates/Repo-rate-table/

But maybe that’s the way it works everywhere. I don’t know.

29. September 2015 at 09:51

Fran, No, the negative IOR would be expansionary. Why did the banks respond with higher mortgage rates? Are you sure it was related to the negative IOR?

Majromax, No, RGDP growth was only about 4.4% in Q2.

Poor Ray, can’t seem to shake off that finance view.

Thanks Jason, I would not have expected a change in 2012.

29. September 2015 at 09:58

Fran, were the Swiss mortgage interest rates long-term? If so, perhaps the negative IOR at the short end was sufficiently expansionary that long term market interest rates increased.

29. September 2015 at 11:04

Excess reserves are about $2.6 trillion right now, and at 25bps that translates to a positive $6.5 billion of income to the banking system. With negative rates of 25bps, this amount would flip to a $6.5 billion loss, which is a little over 8% of 2014 banking sector profits of $152.7 billion.

Since the banking system can’t get rid of reserves, individuals banks would likely take a number of actions to help offset the loss, such as cost cutting, raising fees, increasing credit spreads.

I think the net effect depends on where that $13 billion goes. Presumably it gets paid out to the Treasury by the Fed, and as such would probably be similar to a deficit reducing lump sum tax increase. That seems contractionary, but since negative IOR would probably be interpreted by the market as monetary easing, perhaps the net effect is neutral or even slightly expansionary.

29. September 2015 at 11:30

Scott,

Concerning your criticism of Ray and his “finance view”. Is not “finance” how easy money gets into the economy and creates growth? If not by “finance” then by what other method?

You seem awfully presumptuous that macro-econ trumps real econ. I, and others, believe it is the opposite. That macro is always subservient to real econ and the FINANCIAL decisions individuals make for themselves and the institutions they represent.

29. September 2015 at 11:53

If negative interest rates on reserves increases expected nominal GDP growth, the demand for fixed rate long term loans should rise and the supply of fixed rate long term loans should fall, raising nominal interest rates on long term loans.

Alternatively, the fisher effect implies that higher expected inflation should increase nominal interest rates.

29. September 2015 at 11:54

DougM apparently confused the economics profession with “macromedia.”

29. September 2015 at 12:27

“cutting the IOR is expansionary, even when in negative territory.”

-You sure that wasn’t just due to the expansion of the bond-buying program? I say such small changes in IOR have little to no effect on anything important. The negative IOR might be contractionary, might be expansionary, who knows? This is hardly a good natural experiment for it. The change is too small and it comes with another monetary policy decision at the same time.

“Will the Nordic countries be the first to adopt the sort of cashless 1984-style panopticon state that is so beloved by authoritarians and Puritans everywhere?”

-Probably. Nigeria is trying the same.

29. September 2015 at 12:43

The Swiss mortgage rates are short term variable rates, even though the loans are long term, like almost the whole world. Only the US has long term mortgage rates, thanks to the option borrowers have to remortgage with no penalty or cost. The US is unique.

The Swiss banks acted as a cartel raising 12m mortgage rates to offset the loss of their deposit margin as rates went negative. The authorities were in cahoots as a way of keeping a lid on Swiss property price appreciation.

Swiss local banks also have access to special reserves for their local business deposits with the central bank that don’t pay negative rates. Large deposits lodged via local banks with the central bank do see negative rates, as do foreign banks lodging reserves with the central bank. It is a way of penalising “hot money” from buying Swiss currency.

The overall picture is thus not straightforward. There is no level-playing field.

29. September 2015 at 12:47

@Justin D.

You seem to have a lot of info on excess reserves. The idea of having negative IOR is to force the banks to reduce them (e.g. lending them out). Do you have data on the dynamics of the excess reserve stock ?

29. September 2015 at 12:50

Mattias, Thanks for that info. Do you know if the banks actually pay the minus 1%? I heard there were some loopholes.

Justin, You said:

“Since the banking system can’t get rid of reserves,”

You are missing the point. It’s precisely because the banking system can get rid of excess reserves that it is expansionary. It causes an increase in the currency stock.

Bill, Yes, that’s what I’d expect too, but it doesn’t always seem to work out that way. Not sure why.

29. September 2015 at 12:53

E. Harding, Maybe, but there have been other similar cases.

James, Thanks for that info.

29. September 2015 at 13:16

@Jose,

The problem as I see it is that banks as a whole can’t do anything directly to reduce excess reserves.

Think about it from the perspective of the Fed’s balance sheet. Abstracting away from a slew of additional smaller items, the Fed has assets which largely consist of treasuries and mortgages, and the sum of these equals reserves, currency and government deposits. The only way for reserve balances to change is when the Fed changes its assets, the public changes how much cash it wants to hold, or the government changes how much it deposits with the Fed. Bank lending does not enter into the equation except in how it might affect these other items (e.g. slower bank lending leads the Fed to engage in QE which increase both assets and reserves).

Consider it from the perspective of an individual bank. Suppose I’m a loan officer at a bank that has $1,000 of excess reserves it wants to get rid of. I find a willing borrower and lend $1,000 to him, holding the rest of the balance sheet constant. Unless the borrower is content to keep the money as cash and outside of the banking system (i.e. increase the public demand for currency), that money will be deposited. His bank will see its deposits increase by $1,000, and it will have an extra $1,000 of cash, that is, $1,000 in excess reserves.

So under most circumstances, efforts by one bank to reduce its excess reserves will lead to roughly the same amount of reserves being added by other institutions.

That all said, I admit I’m not certain on how negative IOR affect the economy from a macro perspective. The first order effects seem to be negative, though as I said above, second order effects or the impact on expectations could well offset this.

29. September 2015 at 13:24

@ssumner: the argument for why negative interest rates increased mortgage rates goes as follows: A bank that wants to hedge its interest rate risk for the outstanding eg 10y fixed (!) rate mortgages using a swap instrument would get the corresponding swap rate on the capital market. As 3m Libor is at negative 0.75% and the long run interest rate essentially zero, the bank would have to pay more than it receives for the swap. The difference it has to either make up by increasing the margin on the mortgage or by passing the negative interest rate on to the savers. Yet, this latter possibility is not feasible.

29. September 2015 at 13:49

Scott, Tyler found this.

https://polcms.secure.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/upload/5bcc04fc-0ce1-4934-a240-da5d5249c6a6/KIEL_FINAL.pdf

The actual report to which the Tyler Cowen link takes you says it is only in draft still. It’s not on the official site as far as I can see. It comes out of the secretariat that supports the European Parluament. So who actually sponsored it is unclear.

That said, you should read more than the rather cautious abstract only. The peice is well argued over all. It even includes a nod to you and NGDP Futures. The concluding section is quite a powerful recommendation to look at NGDP Forecast LT.

29. September 2015 at 13:50

I’ll add that I agree the macro evidence from Sweden provides some evidence that negative IOR is expansionary, I just don’t think the reason is because banks lend out excess reserves, taken as a collective group.

29. September 2015 at 15:54

Excellent blogging.

By the way, worth considering is can a modern developed nation with a high tax structure survive a radical increase in cash in circulation?

With cash increasingly used for savings and transactions, it is inevitable that a large off-the-books economy grows.

29. September 2015 at 16:11

@Justin D.

Yes, the money will probably be back as deposit, but before, it will be spent on something, otherwise it would not need to be borrowed. That is exactly what this blog post is claiming, velocity increases, and so does NGDP…

29. September 2015 at 17:09

“And then when the theories are actually tested and the results are in, they keep making the same claims, seemingly oblivious to the fact that their theories have been discredited.”

Maybe they were using the same batch of faulty test tubes you used after the last major FOMC announcement.

29. September 2015 at 17:14

“Yup, cutting the IOR is expansionary, even when in negative territory.”

If the Swedish stock market went up but then back down, you would not then conclude the theory IOR is expansionary has been falsified, you would have said the particular results are inconclusive.

29. September 2015 at 17:17

“So that doesn’t look very good for negative IOR. But recall that in most countries inflation has recently been falling sharply, due to the plunge in oil prices.”

See? No matter the results, there is always an excuse to tip toe around what your “model” says about negative IOR.

29. September 2015 at 17:19

Where is your research and analysis of how inflation distorts economic calculation which then leads to future (which is now present) deflationary forces?

Crickets….

29. September 2015 at 17:49

Sumner: “Poor Ray, can’t seem to shake off that finance view.” – neither could Fisher Black of Black-Scholes fame. Why do you cling to the monetarist view of money non-neutrality? The 3.2 to 13.2% effect of the Fed? As trivial as MF’s rantings.

29. September 2015 at 18:02

Fran – for your postulated channel, did the Swiss commercial banks have to reject storing currency in their own vaults or paying out excess capital? Thanks in advance for your attention!

29. September 2015 at 18:46

Ray,

Why do you cling to the money neutrality myth? Is it because if money were not neutral, you be at a loss to contribute a critique of central banking?

Your rantings of money neutrality are chock full of flaws, contradictions, and ignoring basic math and statistics.

29. September 2015 at 20:22

Justin D: You’ve obviously thought about the excess reserve issue. I’d like to address a few of your thoughts.

You wrote (after noting, accurately, that banks would suffer a $13 billion hit to profits if the Interest Rate on Reserves dropped 50 bp to a negative .25%): “Since the banking system can’t get rid of reserves, individuals banks would likely take a number of actions to help offset the loss, such as cost cutting, raising fees, increasing credit spreads.”

I agree. They would also, as the Swedish bankers did, raise rates on loans and/or cut interest rates on savings deposits. The $6.5 billion interest payment from the Fed to the banking system was viewed as a subsidy, and it’s accurate to view an equivalent $6.5 billion negative interest payment as a tax on the banking system. The banks will pass it along somehow.

You also wrote: “The problem as I see it is that banks as a whole can’t do anything directly to reduce excess reserves.”

I think you’re making an error here in that you’re treating all reserves as excess reserves. Don’t forget required reserves. I suspect that, on considering required reserves, you’ll agree that banks as a whole can indeed directly reduce excess reserves by making additional loans. Doing so will raise aggregate deposits in the banking system and some of the excess position will be converted to required reserves.

In fact, that has been happening already as you can see in the Fed’s H.3 release (see link below). If you examine Table 1, you’ll see that from Aug 2014 to Aug 2015 total reserves have fallen by $178 billion while required reserves have risen by just over $10 billion. (I used a year over year comparison because the numbers are not seasonally adjusted.)

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h3/current/

Of course, since IOR applies to both forms of reserves, the profitability issue you raised isn’t affected.

You then added in a later comment: “I’ll add that I agree the macro evidence from Sweden provides some evidence that negative IOR is expansionary, I just don’t think the reason is because banks lend out excess reserves, taken as a collective group.”

I think if you’ve followed what I’ve said above, you’ll now reconsider that statement, at least as it might apply in the U.S. While the banking system as a whole will still suffer the $13 bn hit to profitability that you raised, any individual bank sitting on an excess reserve position will attempt to get rid of it as soon as the IOR goes negative. They won’t find a fed funds bid to hit, so they’ll become more aggressive making loans, for if they sit on the excess, it will cost them money. Better to lend it and earn some interest.

As you pointed out, though with a slight error in that you forgot that each increase in deposits systemwide shifts some of the excess to required status, the system as a whole won’t be able to reduce the excess reserve position by very much, and certainly not by $2.5 trillion. Still, they will try to circulate their individual excess reserve positions.

The question then becomes, what happens when banks have every inducement to make loans, and no inducement to stop? (Actually, capital constraints will likely become their main constraint, but if a significant inflation resulted, capital would probably grow at a corresponding rate, so maybe it wouldn’t be the constraint it first appears.)

In all of my writings, here and at my blog, I continually refer to a need for the Fed to “neutralize” the excess reserve position if they are to raise the fed funds rate. It would appear that negative IOR would have the reverse effect and would “energize” the excess reserve position, for lack of a better term.

The purpose of a positive IOR is to neutralize the excess to a point, in that it provides individual banks within the system a reason not to aggressively get rid of their excess reserve positions. Clearly, though, given the H.3 data I discussed above, banks are being quite aggressive anyway. That fact has led me to my conclusion that the Fed is now irrelevant to money growth for all intents and purposes. However, if they implement a negative IOR, I might change that conclusion. They’d still have no control over money growth, but the growth rate could certainly be impacted by that decision.

I’d appreciate your further thoughts on this, Justin, as you seem to have a handle on some of the issues involved.

29. September 2015 at 20:32

Scott: You wrote (in a response to Justin D.): “It’s precisely because the banking system can get rid of excess reserves that it is expansionary. It causes an increase in the currency stock.”

I would love to hear your explanation as to how the banking system can “cause an increase in the currency stock.” Yes, banks can request additional currency in lieu of their reserve position, but the resulting vault currency would just count toward the excess reserve position.

Until now, I’ve always been convinced that I determine the amount of currency in my wallet, and not the banking system, and I suspect that is true for every individual, and business, in the country, and outside the country too, for that matter.

So, no, won’t happen. Changes in currency in circulation are due to decisions made by the holders of the currency, not the banking system. By the way, if you ever deign to read my work, that’s a key insight, right there. I’d elaborate, but I’m pretty sure you couldn’t care less.

29. September 2015 at 20:38

A question for someone exceptionally knowledgable of the Swedish banking system: Could you please read my post above this one and then explain how the reserve positions are sorted out in the Swedish banking system? I get lost in the foreign exchange positions, etc., when I go digging myself. In particular, did their bond buying program result in a significant excess reserve position as here in the U.S.? If not, why not? If so, I would be curious how it’s playing out as it could foreshadow what would happen here.

29. September 2015 at 20:50

Ray Lopez: You wrote: “So the have incentive to lend excess reserves. But the incentive is only to the extent they have customers who wish to borrow at a rate greater than what the banks pay the central bank.”

At first glance that made sense to me, but then I realized my error, and yours. The banks will be penalized for holding their excess reserves so they will lend them out at a lower rate than before IOR went negative.

And as I explained in the long post a little above this one, they could be quite aggressive in doing so since there would be a cost to hanging onto them, unlike the present situation where 25 bp seems to satisfy them, as a direct subsidy should.

29. September 2015 at 21:19

@Brent Buckner: Not that I knew. In fact, liquidity withdrawals were more of a thread of some large institutional investors. But I don’t think they actually made this thread real (probably because of the related costs), at least not on a big scale.

29. September 2015 at 23:19

Interesting to see a giant Chinese coal SOE laid off 100K workers. A lot of people are seeing this as bad news, but this is exactly the kind of reform a lot of China bears said China was incapable of doing.

If they give up the peg I’ll have to go back to being optimistic.

30. September 2015 at 05:42

@Rod Everson – “So, no, won’t happen. Changes in currency in circulation are due to decisions made by the holders of the currency, not the banking system.” – I agree. This is in fact a version of “money neutrality”, and therefore Sumner would disagree.

Rod Everson: “The banks will be penalized for holding their excess reserves so they will lend them out at a lower rate than before IOR went negative” – yes, true, but keep in mind no bank (or few banks), if they are prudent, will lend out money if there’s no demand, just to avoid a small penalty interest rate. As you say, if there’s a decent customer of the bank, the customer will get a small break because interest rates just went down. This will increase, at the margin, very slightly, the number of customers asking for a loan, and the bank will thus make more such loans. But a quarter point or even half point or even 100 basis point drop in interest rates is not that big a deal, except to bean counters. Most consumers are not so penny pinched to delay a purchase because of 25 to 100 basis points difference in interest rates. Corporations may be a bit different, as they have accounting departments, but even so, I’ve never seen a corporation make a deal because of just finance. Ergo, Sumner’s negative IOR proposal will just be a small push to banks towards making more loans, not a panacea to jump start the economy as he implies.

@sumner – you should explain what you mean by the ‘finance approach’ instead of just throwing labels around. If you don’t understand something, as you stated in your blog post “well I’m not quite sure why”, then reach out for help. It’s embarrassing for a tenured former professor of economics to be so ignorant, but it’s a lesser evil than perpetuating straw-men and myths about supposed contraction effects of negative IOR.

30. September 2015 at 07:02

Justin, If banks lower the interest rate on deposits it will increase the public’s demand for cash.

Fran, Why are you comparing the Libor to the long run rate? Are you merely arguing that easy money steepens the yield curve?

Rod, You said:

“I would love to hear your explanation as to how the banking system can “cause an increase in the currency stock.” Yes, banks can request additional currency in lieu of their reserve position, but the resulting vault currency would just count toward the excess reserve position.

Until now, I’ve always been convinced that I determine the amount of currency in my wallet, and not the banking system, and I suspect that is true for every individual, and business, in the country, and outside the country too, for that matter.”

You really, really, really need to take my short course in monetary economics. Banks lower the interest rate on deposits, and this increases the public’s demand for currency. It’s that simple.

30. September 2015 at 07:11

“Yup, cutting the IOR is expansionary, even when in negative territory.”

————-

How queer. Large scale asset purchases by a Central Bank and their policy interest rates are not even necessarily correlated. And YOU don’t KNOW what a “base” for the expansion of new money and credit is. The remuneration rate is a credit control device, albeit interest rate targeting, not quantitative easing. The money stock can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit.

K in Alfred Marshall’s “cash-balances” equation is a function of the MoP (means-of-payment money), sought to be held at any given price-level. Thus, given low interest rates, people will hold, and not convert, their money balances into non-monetary assets for small price differentials – thereby reducing the supply of funds and their velocity (holdings which behave in a paradoxical fashion with respect to peoples’ motives).

30. September 2015 at 07:18

Maybe it’s useful to consider an extreme example. Suppose your bank sends you an email telling you as of tomorrow, interest rates on all deposits are negative 50%. Compounded daily.

What do you choose to do with your money?

🙂

30. September 2015 at 07:24

“What do you choose to do with your money?”

——————

Tripe. You load and cock your guns and prepare for a depression.

30. September 2015 at 07:25

“You really, really, really need to take my short course in monetary economics.”

————–

You shouldn’t even be teaching economics. You don’t understand money and central banking. N-gDp targeting proves that.

30. September 2015 at 07:43

Tall Dave,

For some people negative rates on bank deposits already exist, but they are a result of fees. If negative rates were applied to all bank deposits I suspect there would be a transfer of funds from such deposit accounts to accounts that did not apply such a penalty. In other words, the government would attempt to impose a cost and people would find a workaround. Time and resources would be spent for no purpose other than to avoid a regulatory cost.

If the economy cannot perform with zero interest rates then serious people ought to be asking serious questions why this is so.

30. September 2015 at 07:53

I actually think both sides of this argument are right, kinda like a debate over the income and substitution effects. For small amounts of negative IOR, the Hot Potato effect dominates and lending (like labor) rises. For large amounts of negative IOR, substitutes to lending start to dominate. What’s less clear is the net effect of those substitutes.

===

I understand concerns about the banking system’s ability *as a whole* to reduce reserves, but they simply don’t hold for a particular bank. I assume we all agree that this concern is the following:

1) Borrower A gets a loan (initially neutral to me because it sits in his account in my bank)

2) Borrower A buys something from Saver B

3) Saver B deposits said money into his bank

Unless Borrower A holds part of the loan in cash, reserves don’t change. However, unless there’s a 100% chance that Saver B uses the same bank as Borrower A, Borrower A’s bank reduces *their* reserves by lending money. See the Hot Potato Effect.

The next question is whether I can find a Borrower who is safe enough. If my “risk free rate” just fell to -1/4%, I suspect (hope?) we all agree that some marginal projects have become profitable on a risk-adjusted basis. I think most of us assume this is the mechanism that works in positive territory — assuming the change in interest rate is monetary, not real.

From this viewpoint, Scott’s arguments all look sound to me on plausible micro mechanisms.

===

However, I don’t think the counter-arguments are mutually exclusive.

1) It sounds like everyone agrees that the negative IOR has not been passed through to retail customers. However, I think Scott would even admit that banks would do so *at some point*. At -5% IOR, would any bank be willing to pay 0% to customers?

The transition would be a “phase change” of sorts. Most/all of the loans that depended on slightly negative IOR would go away. This is definitely contractionary.

The hard part is what happens when consumers are forced to pull out all their deposits? I don’t know.

– Certainly some increase in cash holdings (contractionary).

– More sophisticated investors could chase returns internationally (Hot Potato).

– My guess is that most deposits end up parked in a bank in a country without negative IOR (neutral). The risk profile there hasn’t changed so loans don’t increase.

Net-net negative retail interest rates are neutral to contractionary.

2) Even if banks were unwilling to expose retail customers to negative rates they would, at some point, be able to shelter the money. The cost to “pay” a third party to vault cash would eventually be lower than the negative IOR. A bank could plausibly issue loans for a negative interest rate on the condition that a borrower use it to buy and vault cash. To ensure the loan is effectively “risk free”, this would be the terms of the loan. Is this demand for cash contractionary or just a neutral shift from bank vaults to private vaults?

At this point, negative IOR stops working and a new “Z”LB has been established at a micro-level. I assume all of the traditional arguments about the yield curve would apply, preventing any more marginal loans. I also assume financial innovation could stay ahead of regulation for long enough to neutralize efforts to enforce lower IOR (if not, see 1).

30. September 2015 at 07:53

TallDave sez: “Maybe it’s useful to consider an extreme example. Suppose your bank sends you an email telling you as of tomorrow, interest rates on all deposits are negative 50%. Compounded daily. What do you choose to do with your money?”

Buy gold, stocks, real estate, convert your deposits into another foreign currency?…duh. But none of that necessarily will jump start the economy…

30. September 2015 at 07:57

Scott: You wrote, “You really, really, really need to take my short course in monetary economics. Banks lower the interest rate on deposits, and this increases the public’s demand for currency. It’s that simple.”

If it’s such a short course, why not offer an explanation here? It ought to be hilarious. By the way here’s a graph of currency in circulation for the past 30 years: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/WCURCIR/

Note that the only obvious blip was at Y2K and that the trend through the first two recessions on the graph (when interest rates were falling) showed no change. Growth of currency in circulation is one of the most stable relationships in the financial world, and has never been related to the level of interest rates, even when they reached 18% on short paper in the early 80’s.

(That said, the squiggle around the time of the financial panic is interesting, and perhaps indicates the extent of the true panic at the time?)

As for anyone else reading this, did a drop in the interest rate on your NOW account, even to zero, ever convince you to stash the money in your billfold instead? Ever? After all, it still earns zero there, but it sure raises your risk of losing it, either by spending or theft. (And, yes, I realize that a negative rate on savings could change that behavior.)

So, no, Scott, I’ll pass on the recommendation to take your short course on econ, but will instead recommend that you take my long course (just six posts, compared to the nine in your “quick intro” though) on how the Fed actually effects policy in a fractional reserve system. You should start with #1:

Monetary Theory: Part 1 – Fractional Reserves

30. September 2015 at 08:00

–“I think you’re making an error here in that you’re treating all reserves as excess reserves. Don’t forget required reserves. I suspect that, on considering required reserves, you’ll agree that banks as a whole can indeed directly reduce excess reserves by making additional loans. Doing so will raise aggregate deposits in the banking system and some of the excess position will be converted to required reserves.”–

Rod, that’s a fair point and I agree with what you say. Strictly speaking, banks can’t get rid of reserves, not excess reserves. An increase in certain types of deposits would convert a portion of excess reserves into required reserves, though the total amount of reserves would remain unchanged. This adjustment would be pretty marginal (as you note, there has only been a $10 billion increase in required reserves in the context of over $2.6 trillion in total reserves).

–“I think if you’ve followed what I’ve said above, you’ll now reconsider that statement, at least as it might apply in the U.S. While the banking system as a whole will still suffer the $13 bn hit to profitability that you raised, any individual bank sitting on an excess reserve position will attempt to get rid of it as soon as the IOR goes negative. They won’t find a fed funds bid to hit, so they’ll become more aggressive making loans, for if they sit on the excess, it will cost them money. Better to lend it and earn some interest.”–

To some extent I agree with this. As far as I can tell the two main constraints for bank lending are capital and demand for credit. Right now, healthy banks are already willing to make an unlimited amount of positive risk-adjusted NPV loans so long as they have sufficient capital to do so. The only factor the banks have any real short term control over is what they consider to be a positive risk-adjusted NPV loan. Banks might be more willing on the margin to extend financing to borrowers with poorer collateral coverage, reduce the amount of covenants on the loan, allow higher leverage ratios for borrowers, etc. Given the hit to profits from negative IOR, I suspect that lowering credit margins won’t be a popular option for expanding lending, and rather banks will be comfortable with a somewhat riskier mix of new originations will be the most likely outcome. That said, I would expect banks to rely more heavily on increasing fee income and cost reduction, as most banks would be wary of dramatically increasing the risk of their portfolios, and in any case the regulators wouldn’t be happy with it. Then there is also the consideration that a riskier portfolio would cause an increase in capital requirements, which in turn could slow loan growth.

Since the total amount of reserves will remain largely unaffected, quite a few banks will still find themselves saddled with large amounts of excess reserves.

30. September 2015 at 08:07

TallDave: You wrote “Maybe it’s useful to consider an extreme example. Suppose your bank sends you an email telling you as of tomorrow, interest rates on all deposits are negative 50%. Compounded daily.

What do you choose to do with your money?”

I’m assuming you’re addressing the argument Scott is making that cutting the rate on deposits increases the demand for currency in circulation (which I disagree with.)

Yes, people would pull money from that bank the day they got the letter, and if all banks decided to go out of business along with your bank on that same day, then currency in circulation would skyrocket. Both Scott and I, however, are assuming a continuation of modern banking in our discussion, so, no, sometimes an “extreme example” is not particularly useful.

That said, those who argue for a negative interest rate are looking for ways to apply some sort of penalty for converting to cash, including advocating doing away with cash altogether. The further down this rabbit hole we go, the more curious it gets.

30. September 2015 at 08:22

Justin: You summarized with “Since the total amount of reserves will remain largely unaffected, quite a few banks will still find themselves saddled with large amounts of excess reserves.”

Yes, absolutely. In fact almost all banks will find themselves with an excess position because fund will be continuously, and possibly furiously, circulating if the IOR rate goes negative.

It remains to be seen how a shift from +25 basis points on excess reserves to -25 basis points affects bank behavior, but I believe it could change dramatically. Why? Because it would be throwing a financial switch, not just modulating an existing situation. Reducing or raising the rate 10 bp would modulate, but going negative is a switch, with unknown consequences in a system filled to the brim with excess reserves.

As long as IOR is positive, banks are getting a subsidy, however large or small, and are satisfied earning it. But if IOR is set at a negative rate, banks will no longer be satisfied sitting on their individual portion of the excess and will find ways to get it off the books. You’re right, of course, that they won’t be able to accomplish this systemwide, but that doesn’t mean they won’t be trying at the individual bank level, and that’s the key.

If the IOR rate goes negative banks will have an entirely new goal, one they don’t have now: Reduce excess reserves to a minimum. That doesn’t mean they’ll sacrifice profitability, as you pointed out, but they will be aggressive in that direction, whereas that is not now the case. Today, they passively sit on their excess reserves. Throwing the switch will reverse their behavior.

And, yes, capital requirements will likely be the main constraint, although if an inflation did result, that constraint would probably gradually loosen.

30. September 2015 at 08:57

@Rod. What happens if the Fed goes back to the way it was before, ie: no IOR? I would consider this to be a “normalization.”

30. September 2015 at 09:16

–“In all of my writings, here and at my blog, I continually refer to a need for the Fed to “neutralize” the excess reserve position if they are to raise the fed funds rate. It would appear that negative IOR would have the reverse effect and would “energize” the excess reserve position, for lack of a better term.”–

I haven’t fully thought through the implications of this, it doesn’t help not having any historical experience. I’ve seen this issue discussed as a concern about whether the Fed could successfully raise the funds rate with such high levels of excess reserves. The most likely vehicle for neutralizing excess reserves in a rising rate environment seems to be the reverse repo facility.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/feds/2015/files/2015010pap.pdf

–“The purpose of a positive IOR is to neutralize the excess to a point, in that it provides individual banks within the system a reason not to aggressively get rid of their excess reserve positions.”–

My understanding is that 25bps IOR exists to keep the Fed Funds rate in the 0-25bps range (with all those excess reserves, no IOR would have pushed the Fed Funds rate to zero). I’m not sure there is a big difference between +25bps or 0 or -25bps on how the bank operates, aside from the direct impact to earnings. To be clear, banks are already very unhappy having a significant portion of the balance sheet earning 25bps, as that’s well below cost of funds.

–“Clearly, though, given the H.3 data I discussed above, banks are being quite aggressive anyway. That fact has led me to my conclusion that the Fed is now irrelevant to money growth for all intents and purposes. However, if they implement a negative IOR, I might change that conclusion. They’d still have no control over money growth, but the growth rate could certainly be impacted by that decision.”–

I think the Fed still has an effect, at least indirectly through the expectations channel.

30. September 2015 at 09:52

Rod — There’s no reason why what’s true at -50% isn’t also true at -5%.

Reducing or raising the rate 10 bp would modulate, but going negative is a switch, with unknown consequences in a system filled to the brim with excess reserves.

There’s nothing magical about a negative nominal rate.

30. September 2015 at 10:05

Dan W — Not proposing negative rates as a policy, just pointing out it’s really easy to understand the incentives.

If we can get to a nominal GDP target, nominal interest rates will gradually rise slightly to new equilibria because markets will expect more inflation (and, eventually, demand more inflation premia) during periods of slower growth.

30. September 2015 at 10:14

Rod — That fact has led me to my conclusion that the Fed is now irrelevant to money growth for all intents and purposes.

CBs can bid on every asset in existence. Central banks can always inflate.

30. September 2015 at 10:59

–“Maybe it’s useful to consider an extreme example. Suppose your bank sends you an email telling you as of tomorrow, interest rates on all deposits are negative 50%. Compounded daily.

What do you choose to do with your money?”–

Transfer it immediately to a bank which isn’t bent on destroying itself. If all banks are doing this, then I second flow5: get ready for some chaos.

30. September 2015 at 11:21

@ssumner: No, I don’t argue with the yield curve. The argument here is that deposit rates can’t go negative, while the interest rate on reserves with the central bank and closely related to that also the interbank short-term rates do. (Rem.: in Switzerland, the central bank sets its interest rate such that the short-term chf Libor reaches a certain desired level.) We could now argue why deposit rates cannot go negative. Some would say because of some fear of a ‘run’, but that is another story. The point here is that the bank cannot pass the negative rates on to the savers, which has an impact on its profitability.

The long and short rates in my previous response were part of my example relating to the swap contract, in which the bank for hedging purposes swaps a fixed interest payment it receives from the mortgage with a variable interest payment. With negative interest rates, one part of the hedge becomes negative. As a consequence, hedging costs went up for the bank.

30. September 2015 at 12:52

Rod, So there’s about 500 money demand studies that show currency demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates, and I’m supposed to take your word that all these studies are wrong?

Actually the C/GDP ratio fell during the long period of rising interest rates (1945-81) and the ratio has risen since rates started falling. The series is smooth because there are major costs in quickly adjusting currency hoarding stocks. You might want to read my PhD dissertation, which was on currency hoarding demand.

Fran, I don’t know whether deposit rates can or cannot go negative. Service fees seem to me like negative interest rates. But none of this has any bearing on my claim that negative IOR is expansionary for NGDP.

30. September 2015 at 13:01

As to the last graph – Sweden is actively pushing to reduce or eliminate use of physical cash. Handelsbank and Nordea have started introducing cash-less branches IIRC

30. September 2015 at 13:02

Chuck E: You asked: “What happens if the Fed goes back to the way it was before, ie: no IOR? I would consider this to be a ‘normalization.'”

The IOR tends to an extent to neutralize the excess reserves in the system. Whether the Fed believes that might be open to question, but that’s how I see the IOR working.

By “neutralize” what I actually mean is that it gives banks an incentive to hold them rather than aggressively attempting to get them off their individual balance sheets.

So, yes, abandoning the IOR would be a return to what we had before, but with $2.4 trillion in excess reserves in the system today, the situation would be anything but normal.

And, in fact, the IOR doesn’t completely neutralize the excess reserve position. Note that demand deposit growth has proceeded at a greater than 20% clip for five years now (at least through February of this year it did) so the some of the excess reserve position is slowly being converted to required reserves.

30. September 2015 at 13:22

Justin D: Your wrote: “The most likely vehicle for neutralizing excess reserves in a rising rate environment seems to be the reverse repo facility.

That’s correct. It is the most likely, although the Fed could consider doing some significant term repos instead of short-term ones. For example, they could do $2.1 trillion of six-month reverse repos and then drain the rest with overnights.

The only other option I see is liquidating their portfolio. They are apparently in the process of slowly doing that since total reserves have dropped $178 bn over the past 12 months ending August, but a liquidation of the size needed would drive the bond market bonkers, and put the Fed’s entire portfolio underwater besides.

You also wrote: “My understanding is that 25bps IOR exists to keep the Fed Funds rate in the 0-25bps range (with all those excess reserves, no IOR would have pushed the Fed Funds rate to zero). I’m not sure there is a big difference between +25bps or 0 or -25bps on how the bank operates, aside from the direct impact to earnings. To be clear, banks are already very unhappy having a significant portion of the balance sheet earning 25bps, as that’s well below cost of funds.”

Just to show how clueless the Fed was when it initiated all this (the IOR and QE’s), they initially set the IOR well below the existing fed funds rate and linked them, so it was always supposed to be the same amount of basis points below funds. But the massive excess position from the QE’s had banks rationally hitting every funds bid until the Fed relented and set the IOR independent of the funds rate. The banks then drove the fed funds rate to the IOR rate, and non-bank financial organizations drove it even lower, necessitating the Fed’s new repurchase facility so that funds would trade at a marginally positive rate. (Note: I’m writing this from memory without checking the details; parts might be inaccurate.)

Also, I don’t see why banks would be at all unhappy with the Fed providing them a $6 bn subsidy every year for the privilege of sitting on a massive balance in their Fed accounts. Maybe I’m missing something regarding the impact on their capital structure, but it looks like a straight gift from the Fed to the banks to me.

As for the difference between +25bp and -25bp for the IOR, I’ve tried to explain my thinking on that already. Individual banks will become far more aggressive moving the excess off their books, even though in aggregate they won’t be successful. My 40 years of experience watching the Fed has convinced me that such behavior could be extremely expansionary.

Finally, you wrote: “I think the Fed still has an effect, at least indirectly through the expectations channel.”

Probably. Whenever I state that the Fed has become irrelevant, or is no longer effective, what I really mean is that they no longer have the remotest means of fine-tuning monetary policy, or at least the intended results of monetary policy. They’ve completely lost control of the money supply, a control they once held quite tightly, and they won’t get it back until they return to a time when the excess reserve position is back to frictional levels. And even after that happened some changes need to be made so that demand deposits are minimized by their holders.

30. September 2015 at 13:30

Scott, you wrote: “Rod, So there’s about 500 money demand studies that show currency demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates, and I’m supposed to take your word that all these studies are wrong?”

No, just look at the graph for goodness sakes.

Interest rates rose and fell for decades and currency in circulation just kept moving relentlessly upward all the same. Other than that one drop during the financial panic of 2008/09, I challenge you to show me any time over the past 60 years where currency noticeably slowed its growth in response to a rise in rates, or where it noticeably grew faster in response to a fall in rates, for that matter.

You can’t support your argument with a 30-year trend in rates, either. Short term rates have oscillated all over the lot during the past 60 years. Show me one chart that shows currency rose and fell in response, or even slowed or increased in response. Just pull a chart out of one of those 500 studies you claim support your case.

Frankly, if you can produce such a chart I will be amazed because what you’re claiming simply doesn’t, and hasn’t ever, happened, at least in the modern banking era, in the U.S.

30. September 2015 at 13:56

Rod, Doesn’t Currency in Circulation need to move upward due to demographics? It seems that currency would follow population growth.

30. September 2015 at 14:18

–“Justin, If banks lower the interest rate on deposits it will increase the public’s demand for cash.”–

I agree.

30. September 2015 at 14:50

–“Also, I don’t see why banks would be at all unhappy with the Fed providing them a $6 bn subsidy every year for the privilege of sitting on a massive balance in their Fed accounts. Maybe I’m missing something regarding the impact on their capital structure, but it looks like a straight gift from the Fed to the banks to me.”–

It’s a cost of funds issue. Assets on the balance sheet need to be funded with liabilities or equity. If the liabilities cost more than the rate on a particular asset, then holding that asset will reduce earnings.

Consider COFI-11: this index is a blend of checking and savings rate in the 11th Fed district, and is currently 64bps. If we take this to be indicative of a typical bank’s cost of funds, then Fed Reserve balances reduce aggregate bank earnings by $10.1 billion/yr. COFI-11 actually might be a bit low, given that it only considers deposit accounts and other types of funding, such as equity or bank notes, are more expensive.

http://www.bankrate.com/rates/interest-rates/11th-district-cost-of-funds.aspx

Note also that, because cost of funds will decline in a negative IOR environment (especially if banks begin charging for deposits), the impact to the bottom line of banks won’t be 50bps, but probably something closer to 10-20bps. Still bad, but not as bad as the IOR change makes it seem.

–“As for the difference between +25bp and -25bp for the IOR, I’ve tried to explain my thinking on that already. Individual banks will become far more aggressive moving the excess off their books, even though in aggregate they won’t be successful. My 40 years of experience watching the Fed has convinced me that such behavior could be extremely expansionary.”–

It’s certainly possible. Without historical experience I can’t say that it wouldn’t happen, but my sense is that there are limits to how much banks can do. Already seeing net interest margins hit due to negative IOR, I think banks would be allergic to lowering credit spreads. Banks can purchase other assets, but yields will be very low, especially if the assets are swapped to hedge interest rate risk exposure. Banks can decide to loosen credit standards and make riskier loans, but capital ratios are calculated based on risk weighted assets, and a riskier book will require more capital all else equal. The large banks all have to present capital plans annually to the regulators based on stress test results, and a riskier book would likely perform poorly in the severe stress scenario, possibly leading the regulators to reject management’s capital plan. There might be ways around this, or some other factors I’m not considering, but for now, while I accept that on the margin you might get a little boost in lending, it will be pretty marginal and come with the cost of a (marginally) riskier banking system.

30. September 2015 at 14:56

–“Rod, Doesn’t Currency in Circulation need to move upward due to demographics? It seems that currency would follow population growth.”–

It actually grows much faster than population. Currency held by the public has risen faster GDP, as the ratio of currency to GDP was about 4.5% in the late 1970s, 5.5% in the late 1990s, and 7.5% over the past two years on average. This actually surprised me, as I would have thought increased use of electronic forms of payment would have worked against rapid growth in currency, but that’s might just be millennial bias.

Per Scott’s comment regarding public demand for currency, there does seem to be correlation with rates, with stronger growth relative to GDP when interest rates are low (2001-2003, 2008+).

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/WCURCIR

30. September 2015 at 15:01

Rod,

See this chart (currency in circulation / NGDP). There seems to be some correlation between this ratio and rates.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?chart_type=line&recession_bars=on&log_scales=&bgcolor=%23e1e9f0&graph_bgcolor=%23ffffff&fo=verdana&ts=12&tts=12&txtcolor=%23444444&show_legend=yes&show_axis_titles=yes&drp=0&cosd=1984-01-04&coed=2015-09-23&height=445&stacking=&range=&mode=fred&id=WCURCIR_NGDPPOT&transformation=lin&nd=&ost=-99999&oet=99999&lsv=&lev=&scale=left&line_color=%234572a7&line_style=solid&lw=2&mark_type=none&mw=2&mma=0&fml=a&fgst=lin&fgsnd=2007-12-01&fq=Weekly%2C+Ending+Wednesday&fam=avg&vintage_date=&revision_date=&width=670

1. October 2015 at 01:48

“Interesting to see a giant Chinese coal SOE laid off 100K workers.”

Looks to me like they are correctly reasoning from a price change…

1. October 2015 at 06:55

Chuck E: You wrote “Rod, Doesn’t Currency in Circulation need to move upward due to demographics? It seems that currency would follow population growth.”

I suppose it would. It would also follow the inflation rate in a monetary system like the U.S. In addition, foreign demand for U.S. dollars can vary depending upon a lot of factors.

My point wasn’t to put together a model of the growth of currency in circulation. It was to rebut Scott’s assertion that currency in circulation responds to interest rate changes; it doesn’t, but tends to grow steadily despite significant fluctuations in interest rates.

And that discussion ensued only after he made the claim that excess reserves would be converted into currency in circulation, which is unsupportable as well.

1. October 2015 at 07:12

Justin, you wrote: “Per Scott’s comment regarding public demand for currency, there does seem to be correlation with rates, with stronger growth relative to GDP when interest rates are low (2001-2003, 2008+).”

With all due respect, that’s pure confirmation bias at work on your part. Picking out a small time slice of a chart while looking for a correlation (correlation, not causation).

Take a look at the wild swings in interest rates in the 70’s and see if you can detect any reverse correlation between interest rates and currency in circulation.

Currency growth tends to lag the inflation rate, so if you go from high inflation to low inflation, currency growth will tend to slow, but many other factors affect currency growth including how prosperous the drug trade is at the time, etc. Foreign holdings of U.S. currency are significant.

I will admit to being mystified at the significant growth in currency over the past few years, but I would bet that it’s not because you’re carrying an extra wad of cash because your NOW account isn’t paying you a decent interest rate today.

It could even be due to the general concern among a fair share of the population that the economic system is broken. ln fact, it wouldn’t surprise me to find a stronger correlation between gun sales and currency in circulation than between interest rates and currency.

Again, this whole discussion started when Scott claimed that excess reserves would be converted into currency in circulation, an absolutely unsupportable assertion, but now, as usual, he’s got us running around the rabbit hole discussing a minor side issue.

1. October 2015 at 07:42

Justin, I was going to ask a bank capital question, but in formulating it came up with another issue instead that you might be able to shed some light on.

The Fed did around $2.5 trillion in QE’s. There were two sources of the securities they purchased, banks and bank customers.

The securities from the banks were replaced by an excess reserve asset at the Fed.

The securities from the bank customers were replaced by customer deposits at the banks. Initially those would have been demand deposits, but while demand deposits saw excessive (20%+) growth over the last five years, they still only grew around $600 bn or so.

Do you have insight as to where those newly-created demand deposits went. As I think about it, they could have been used to pay down loans, reducing both deposits and loans, or they could have been converted into time deposits, which I suspect is more likely, but maybe I’m missing something?

1. October 2015 at 07:48

Justin, following up on the capital issue now:

If the Fed does an $1 trillion QE, the banks end up with $1 tn in excess reserves at the Fed as an asset earning 25 bp. They also, per my question to you above, end up with some combination of higher demand deposits and time deposits, as well as some downward pressure on loans on the books. Assume the loan issue is minor and just consider the deposit increases.

From what you’re saying then, banks do not like a situation where they have acquired a huge asset earning 25 bp that is offset by a similarly huge deposit liability, some of which they pay interest on besides.

Is that an accurate presentation of how you see it? If so, I can see the point that banks wouldn’t exactly prefer the situation. However, the asset is 100% secure. Does that affect things too, or do you see it as disadvantageous to the banks regardless.

Thanks, by the way. This could change my thinking on the “subsidy” depending on how the discussion sorts out.

1. October 2015 at 18:08

Rod, You said:

“Scott, you wrote: “Rod, So there’s about 500 money demand studies that show currency demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates, and I’m supposed to take your word that all these studies are wrong?”

No, just look at the graph for goodness sakes.

“Interest rates rose and fell for decades and currency in circulation just kept moving relentlessly upward all the same.”

This afternoon I saw a Fed official present a paper that showed for the 501th time that money demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates, using sophisticated econometrics. And you just tell me to look at the graph. You are making kindergarten level errors in your comments. Is the graph C or C/NGDP? Are you accounting for lags? Let me guess—no. Have you accounted for taxes? Again, I’d guess no.

2. October 2015 at 07:31

Scott, this is the best discussion of actual monetary mechanics that I’ve seen here in a while.

My question regards statutory limits on currency withdrawal. You are legally intimidated from withdrawing any sizable volume of currency in the US. In short, you cannot get your money out of the bank in currency terms.

I’d imagine that you would say that these statutory currency restrictions signify tighter money. Would easing up restrictions on cash boost NGDP?

Banks cannot create demand for currency, but exactly how can you know what demand for banknotes is if you limit withdrawals? There could be immense pent up demand for banknotes right at this moment. Banks restrict the supply of currency every day.

They limit cash withdrawals in Greece, don’t they. Ergo, availability of currency is not a demand side only phenomenon.

Empirically, reserves relate to short rates, MZM to long rates, and currency to NGDP. That’s your monetary identity.

2. October 2015 at 07:41

Scott, you wrote: “This afternoon I saw a Fed official present a paper that showed for the 501th time that money demand is negatively related to nominal interest rates, using sophisticated econometrics. And you just tell me to look at the graph. You are making kindergarten level errors in your comments. Is the graph C or C/NGDP? Are you accounting for lags? Let me guess””no. Have you accounted for taxes? Again, I’d guess no.”

And still you have no link, no evidence, just assertions. And I’m the kindergartner here?

I showed you a graph that showed steady growth in currency over many years when interest rates fluctuated significantly. You’ve asserted. I’ll leave it at that.

2. October 2015 at 07:51

jknarr: While there are reporting requirement in the U.S. if one withdraws more than $10,000 (or deposits it, for that matter) those are aimed at lawbreakers operating in the cash economy such as drug dealers and fences.

You can withdraw, and stuff into your mattress, wallet, or safe deposit box, as much currency as you want. But if it’s done in large amounts it will be reported and you might even get some scrutiny from the Feds (not the Fed, the Feds). And the amount that triggers it might now be $5,000. I’m not sure.

You’re absolutely right, though, when you say that banks cannot create demand for currency. That decision is up to the individual or the business entity.

You’re also onto something when you say currency relates to NGDP, but not in the way you think. In fact, currency growth responds to inflation in an economy that is based primarily upon a fractional banking system. It doesn’t precede, nor cause, NGDP growth. That typically only happens in countries where a hyperinflation is underway and the government is literally running the printing presses to pay its bills. That’s not the case here, in a literal sense at least.

2. October 2015 at 08:36

Rod, government and the banks collude to stop citizens from accessing base money in any significant volume. The real value of 10,000, 5,000 shrinks every day. Those are the laws, of course. Have you actually ever tried to withdraw a sizable amount of currency. By appointment only, with suspicion and reluctance. They get paid for holding reserves, not by handing out that cash to the lumpenproles.

They limit currency to law abiding citizens, and then complain that criminals are the only users of cash — which of course justifies a crackdown on criminal usage of cash. A nice rhetorical trick, no? You’re falling for it.

Banknotes are the public deliverable for all financial obligations. It’s thus end of the road. Even reserves are only a currency deliverable. Affect this numinaire, affect all financial assets (NGDP).

2. October 2015 at 08:46

Scott, this points at a new pathway for IOR being a enormous tightening on NGDP.

Banks are less likely to want their IOR paying reserve assets to walk out the door as banknotes. You have a financial incentive for banks to kill currency.

IOR is a Trojan horse in the war on cash.

2. October 2015 at 08:52

Rod, don’t misunderstand me, banks set the demand for zero-yielding currency via the short rate. No interest, no compensation for the unsecured liability bank counterparty risk? Take the zero-counterparty-risk CB obligation any day.

Or has the bank meltdown of 2008 faded so fast? No such thing as a bail-in, eh? Ask the Greeks and Cypriots.

2. October 2015 at 12:36

–“With all due respect, that’s pure confirmation bias at work on your part. Picking out a small time slice of a chart while looking for a correlation (correlation, not causation).”–

I don’t think it’s fair to consider it as confirmation bias – I after all initially began this thread as being skeptical regarding the efficacy of negative IOR aside from expectation effects.

–“Take a look at the wild swings in interest rates in the 70’s and see if you can detect any reverse correlation between interest rates and currency in circulation.”–

Rates did swing wildly, but from one high number to another. If rates are swinging between 7% to 9% to 11% back to 8%, however you slice it, there are large opportunity costs to holding money as currency.

If you consider rate environments as falling into three types: low, moderate and high, then I do think rates and currency holdings are positively correlated.

As Scott says, there are more detailed studies of the matter if that’s too ad-hoc for you, but to me it seems hard to dispute Scott’s basic contention that there is some evidence rates have an impact on currency balances, and that evidence is consistent with intuition about opportunity costs.

2. October 2015 at 13:45

jknarr, Those restrictions would reduce the effective demand for currency, which is expansionary.

Rod, OK, you keep looking at graphs and tell me when you discover the key to monetary economics.

There are hundreds of studies of money demand. If you haven’t read any of them, and need me to point them out, then you are not competent to be blogging on monetary economics.